This commentary represents the research and views of the authors. It does not necessarily represent the views of the Center on Global Energy Policy. The piece may be subject to further revision. This commentary was funded through a gift from G. Leonard Baker, Jr. More information is available at Our Partners.

As the United States and Europe navigate a difficult and uneven shift toward full battery electric vehicles (BEVs), the US and EU auto markets are under heavy pressure, lagging China’s market in terms of supply chain and battery technology readiness. In the US, the Trump administration is rolling back Biden-era electric vehicle (EV) policies, and its newly imposed tariffs may increase BEV prices, potentially slowing the pace of transition to BEVs. In this context, US and EU policymakers and automakers are reassessing where plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs) fit within their industrial and climate strategies. The idea is that, given the US’s and EU’s less-developed minerals and battery sectors, range anxiety, and slowly developing charging infrastructure, PHEVs—with their smaller batteries relative to BEVs—can serve as a bridge technology that still offers carbon-reduction benefits.

This theory appears intuitive, but whether it maps with the projected global competitiveness and relevance of PHEVs remains an open question. This commentary analyzes current market and technology trends to better understand the future of PHEVs in an increasingly electrified transportation market. These trends indicate that PHEVs are unlikely to serve as a durable path for the US and Europe to achieve global EV competitiveness. Instead, their value lies primarily in serving as a transitional complement within domestic markets, provided policymakers address real-world emissions gaps, cost barriers, and supply-chain vulnerabilities that extend from China’s dominance. In other words, PHEVs can play a role in specific market segments and extend the utilization of the industrial base and therefore jobs in the short-term, but they can’t do so beyond this since both BEV and PHEV competitiveness is built on battery competitiveness now concentrated with Chinese players.

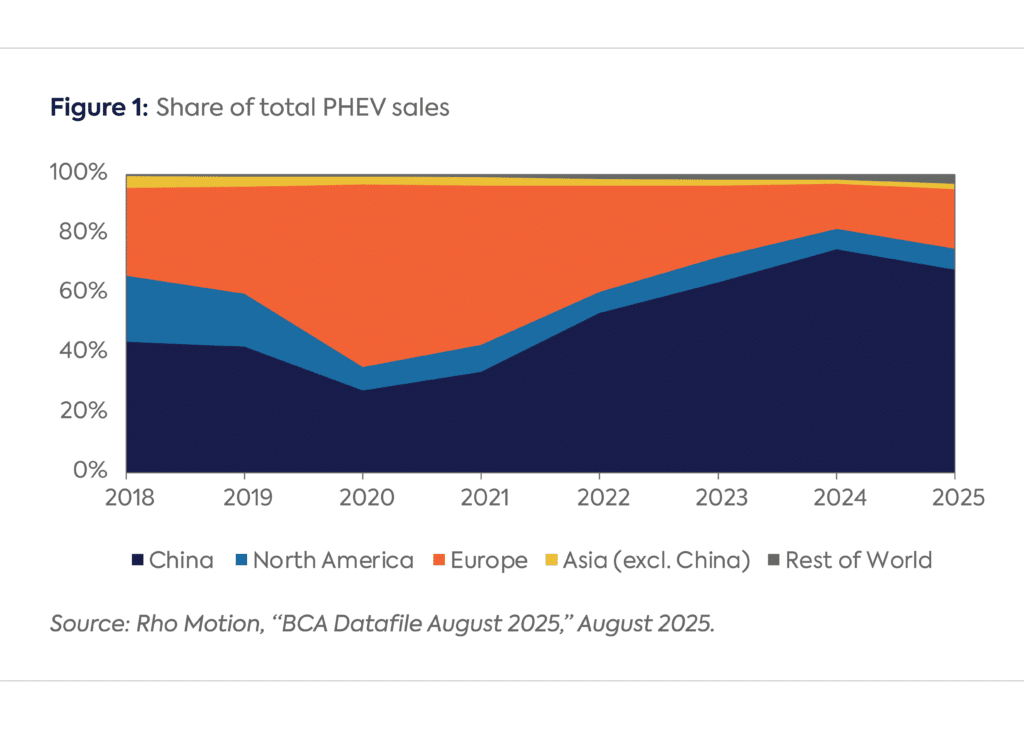

Global EV sales reveal an evolving dynamic between BEVs and PHEVs. In the early years of market growth, up to 2018, PHEVs were a popular entry point for consumers transitioning away from internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs), representing about 40 percent of total EV sales. As technology advanced and battery prices fell, BEVs surged to nearly 70 percent of total EV sales between 2018 and 2024, supported by policy incentives and growing consumer confidence in charging infrastructure.[i] Since 2024, PHEVs have grown only modestly, accounting for roughly one-third of global sales versus two-thirds for BEVs through mid-2025.[ii] In 2024, there were around two BEV models for every PHEV model available in China, Europe, and the United States. Globally, the ratio was over three to one.[iii]

Much of this dynamic has been shaped by China, which has looked at transport electrification as a way to compensate for its competitive disadvantage in ICE markets. Chinese demand today accounts for 67 percent of global PHEV sales and 56 percent of BEV sales.[iv] This is largely explained by China’s early investments in battery manufacturing and supply chains, which cemented its global leadership in EVs. China currently maintains the broadest support for PHEVs of any country in the world through a combination of incentives, including a 10 percent vehicle purchase tax exemption to production-side credits.[v] Europe, whose PHEV market is mostly geared towards high profit margin premium models, represents around 20 percent of global PHEV market share.[vi] The US follows in third place, at around 7 percent, with the few supportive federal policies that had been in place being rolled back over the past year, though PHEV support persists via California’s Zero-emission Vehicle Regulation.[vii]

PHEVs have also benefited from broader technological advancements in the EV industry, which is building next-generation batteries with higher energy densities and longer ranges. The size of PHEV battery packs has increased from an average of 13 kilowatt hour (kWh) in 2018 to 23 kWh by 2025, and thus allowed for longer electric-powered ranges.[viii] However, because PHEVs must accommodate both a battery pack and an ICE, they require two parallel and therefore complex propulsion systems that make their average price per kWh higher than that of BEVs, by roughly three times in 2024.[ix] In 2024, affordable PHEV options were limited in Europe and the United States, with only one model priced below $40,000 in Europe and four in the United States, while China stood out with nearly 40 models under $25,000.[x] Conversely, in China, PHEV prices have consistently dropped as a result of the country’s competitiveness in batteries: the sales-weighted average for medium-sized PHEVs in 2024 was 10 percent lower than conventional models in the same category, causing PHEV sales in the sector to more than double.

A key appeal of PHEVs lies in their ability to handle longer trips even when charging infrastructure is insufficient or congested. In China, this advantage has been reinforced by steady improvements in range: between 2020 and 2025, the electric-only range of PHEVs grew by more than 20 percent, reaching nearly 100 kilometers. By contrast, ranges in Europe and the United States have plateaued at around 65 kilometers.[xi]

Another distinct advantage of PHEVs is their lower mineral intensity. In 2025, European BEVs had an average pack size of about 70 kWh, compared with 19 kWh for PHEVs, in the passenger and light duty vehicle segment. In the US, it was 94 kWh compared with 19 kWh.[xii] US and European BEV and PHEV batteries also include a heavy makeup of nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM) battery cells, which use more and more expensive critical minerals compared with LFP batteries. This means that, all else being equal, European and US PHEVs use three to four times less critical minerals than BEVs. In a context of critical mineral supply constraints and chokepoints,[xiii] they may therefore enable more drivers to shift to electric cars more quickly, with a spillover effect on demand for supporting infrastructure, particularly charging infrastructure. This can certainly be a boost to electrifying the transport sector, if drivers primarily use their batteries (see below). But a broader shift to PHEVs does not necessarily mean global competitiveness (see below also).

As with BEVs, China leads the global PHEV market, bolstered by favorable policy, consumer enthusiasm for Range-Extended Electric Vehicles (REEVs), and ongoing government incentive programs.[xiv] Chinese PHEV sales are expected to reach around 8 million units by 2030 in the base scenario and 9.3 million units in the upside case, compared with 1.6 to 1.7 million in Europe and 1.2 to 1.4 million in the US.[xv] While this suggests growth potential for Western markets, it also reflects China’s enduring grip on PHEV markets and models.

China’s dominance in the sector raises the question of whether a strategic refocus on PHEVs could allow Western automakers to compete globally, rather than solely within domestic markets. Given that PHEV competitiveness is tightly linked to battery manufacturing capabilities, countries applying tariffs to shield domestic BEV and battery industries may find themselves at a disadvantage in exporting PHEVs. Under such conditions, PHEVs could support national transition goals but are unlikely to generate new global leaders in transport electrification.

Domestic appetite remains notable, however. In the US, BEVs and PHEVs accounted for 8 percent and 2 percent of new passenger car sales in 2024, respectively—and these shares are expected to grow to 26 percent and 17 percent by 2034.[xvi] This suggests PHEVs will continue to have a role in the transition, even as global markets favor full electrification. Despite the expiration of federal incentives in the US in 2025, analysts still project steady, albeit slower, growth in broader EV uptake, suggesting that consumer interest is proving more stable than policy.[xvii] Still, in a global context, the trend is toward full battery electrification, with PHEVs increasingly acting as a transitional technology whose relevance narrows as infrastructure, costs, and regulations evolve in favor of BEVs. In China, 2024 BEV and PHEV sales stood at 26 percent and 19 percent, respectively, with PHEVs expected to peak near 30 percent in 2032 before declining to 18 percent by 2040 as BEVs reach 80 percent. Europe follows a similar path: BEV and PHEV shares were 14 percent and 6 percent in 2024, and projected to reach 67 percent and 8 percent by 2034, consistent with Europe’s policy focus on full electrification.[xviii] In 2025, PHEV sales climbed by almost 60 percent year on year, which analysts say reflects temporary policy and registration effects rather than a structural shift away from BEVs.[xix]

Battery demand further illustrates the growing divide between BEVs and PHEVs. In 2024, BEVs accounted for 148 gigawatt hours (GWh) of battery demand in Europe and 112 GWh in the United States, compared with just 17 GWh and 6 GWh from PHEVs. The battery share in the US for PHEVs was mostly NCM chemistries, comprising more than 99 percent of battery share in 2025.[xx] This contrasts with China, where lithium-ion phosphate (LFP) technology—used in 61 percent of PHEV batteries and projected to reach 76 percent by 2030[xxi]—has driven down costs and reinforced China’s structural advantage in PHEV battery pricing. These lower costs cascade into final vehicle prices, further strengthening China’s competitiveness.

Automakers and suppliers are increasingly pressing for PHEVs to be recognized as part of Europe’s decarbonization pathway. The German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA) has recommended maintaining PHEVs beyond 2035 and easing regulatory adjustments, arguing that hybrids can help preserve industrial capacity and employment across the automotive value chain.[xxii] Similarly, the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) and the European Association of Automotive Suppliers (CLEPA) have stressed a technology-neutral approach, noting that high electricity prices, trade tariffs, and uneven charging infrastructure require flexibility in compliance pathways.[xxiii]

This lobbying reflects not only industrial and job-protection motives—the European automotive sector employs over 13 million people[xxiv] and PHEV manufacturing may preserve existing supplier ecosystems—but also changing market dynamics: forecasted PHEV sales are rising for most years, and imports from China surged from 31,000 in 2024 to 46,000 in the first half of 2025, largely driven by BYD and Chery New Energy, which are taking advantage of PHEVs not being included in the EU’s additional duties.[xxv]

Market projections show that the absolute number of PHEVs sold will indeed increase in the medium-term (albeit slower than BEVs). The purpose of this increase, however, is not dictated by the data but instead will be determined by policy. PHEVs can function either as a detour that slows full electrification or as a limited but useful boost to electric driving, lower mineral demand, and scaling domestic battery and charging ecosystems. Different actors hold different preferences: some automakers see PHEVs as a way to preserve existing supply chains and employment, while regulators focused on long-term decarbonization increasingly worry about real-world emissions and lock-in risks. If the strategic goal is full electrification—an assumption that cannot be made for the US under the Trump administration—then the following challenges will need to be addressed for PHEVs to make a meaningful contribution.

PHEV pricing shows no consistent pattern across global markets, reflecting differing policy priorities and manufacturer strategies. While the general expectation is that PHEVs will cost less than BEVs due to their smaller batteries, they have become increasingly expensive relative to ICEVs—by over 30 percent for midsize cars and 50 percent for SUVs since 2022—partly because fixed battery system costs are spread over fewer cells and their pack designs are complex and as such add costs.[xxvi] In Europe, PHEVs remain the most expensive option across all vehicle categories, with only one of roughly 130 models priced below $40,000, compared with more than 40 BEVs and 155 ICEVs under the same threshold.[xxvii] In the United States, prices vary by segment: PHEVs are cheaper than BEVs in some SUV categories but considerably more expensive in others. In China, PHEV prices fell in 2024 while those in Germany rose, reflecting the influence of larger battery packs and domestic supply chain dynamics.[xxviii] The result is a fragmented pricing landscape in which PHEVs occupy multiple strategic roles—premium compliance vehicles in some markets, affordable entry-level hybrids in others—creating uncertainty for both automakers and consumers about the long-term position of these vehicles in the electrification transition.

REEVs—a type of PHEV that uses an ICE to recharge the battery when depleted—previously emerged as a way to appease consumer range anxiety concerns, illustrating both the flexibility and uncertainty facing the electrification of transport. In China, REEVs doubled their market share in 2024 from 5 percent to 12 percent before BEVs gained ground.[xxix] This temporary surge was viewed as evidence of REEVs’ potential as a transition technology when supported by strong policy incentives—such as China’s vehicle trade-in schemes—and appealing OEM offerings from manufacturers like Li Auto and BYD. Outside China, however, REEVs remain niche, with only 2,515 registrations in the first half of 2025, [xxx] though the United Kingdom and a few European markets have seen some uptake. Automaker strategies reflect these divergent signals: while groups like Volkswagen and Stellantis have reaffirmed their commitment to fully electric production, others continue to see hybrid and range-extended technologies as useful bridge options, particularly in regions where charging networks remain uneven. Yet it is unclear whether broader REEV adoption would meaningfully accelerate electrification or lower emissions, as these vehicles still rely on combustion engines for part of their range and may replicate some of the behavioral challenges observed with PHEVs.

PHEVs are often promoted as a lower-emission alternative to ICEVs, but real-world data has shown that they can emit nearly five times the official stated emissions and about the same as ICEVs, mostly due to usage patterns and the amount of time users are running on electricity versus fuel combustion. The mismatch between expected and actual emissions has accelerated efforts—mostly in Europe—to phase out PHEV subsidies, with the UK going as far as banning PHEV and hybrid EV sales by 2040.[xxxi] Remaining incentives are now conditional (based on electric range or corporate fleet use) and are being phased out in favor of zero-emission BEVs.[xxxii] As governments tighten climate targets, many automakers are accelerating their transition towards fully electric vehicles over hybrids. In the EU, stricter fleet-wide CO2 emission limits are pushing manufacturers to increase BEV sales to avoid financial penalties. This regulatory shift may gradually become hostile to PHEVs, particularly as questions continue to surface in Europe about their real-word emission performance.[xxxiii] For PHEVs to play a bigger part in transport decarbonization pathways in Europe and beyond, this element is a key area to address. Indeed, countries outside of Europe that are working on reducing their carbon footprint in transport may favor BEVs if they lack evidence that PHEVs have contributed to emissions reduction in advanced economies like the US and EU.

The United States and Europe still face a narrow window in which PHEVs can play a constructive role in marrying automaker competitiveness with decarbonization by sustaining consumer engagement in electrification, supporting segments where charging access remains uneven, and preserving parts of the existing automotive supply base during a difficult transition. Yet these benefits do not alter the structural reality that China’s dominance in PHEV-relevant supply chains (particularly LFP and low-cost pack integration) limits the extent to which hybrids can meaningfully strengthen Western global competitiveness in an increasingly electrified market. In global markets, the long-term signals are clear: BEVs continue to gain ground as infrastructure expands, costs fall, and regulatory frameworks tighten around real-world emissions.

If PHEVs are to function as complements rather than detours, policy design will be decisive. The US and EU Governments could take the following steps:

Together, these measures can allow PHEVs to serve the narrow but highly useful purpose of supporting the electrification transition by easing short-term market pressures while keeping long-term industrial competitiveness at the center of policy.

Victoria Prado is a Research Associate at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, where she integrates the Trade and Clean Energy Transition initiative and conducts research on the geopolitics of critical minerals in Latin America. She was the first hire at a successful climate startup in Brazil, where she supported investor rounds, led the business intelligence team, and gained hands-on experience with carbon markets in emerging economies. Victoria also worked at the Rockefeller Foundation, advancing projects to expand energy access, accelerate coal phase-out in Southeast Asia, and deploy clean energy storage solutions in sub-Saharan Africa. Her work lies at the intersection of climate policy, sustainable development, and global energy systems, with a regional focus on Latin America. She holds a Master of Science in Sustainability Management from Columbia University and has experience in advising major players in Brazil’s oil, gas, and mining sectors on long-term sustainability strategy.

Dr. Tom Moerenhout is a Professor at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and leads the Critical Materials Initiative at Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy. His work extends to roles as Senior Advisor at the World Bank Energy and Extractives Group, Executive Director at the Geneva Platform for Resilient Value Chains, and Senior Associate at the International Institute for Sustainable Development and Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals and Metals. He has served as Visiting Professor at NYU, Sciences Po Paris, and the Geneva Graduate Institute.

Tom specializes in the intersection of geopolitics and industrial policy, particularly as they relate to energy, critical minerals, and battery supply chains. His work focuses on integrating the interests and influence of multiple actors across complex political economies to improve supply chain security and resilience. Tom has published extensively on sustainable development and energy policy reforms, specifically on energy subsidies, critical materials, and the economic development of resource-rich countries.

He has advised and consulted for various stakeholders, including the White House, Departments of Energy and State, USTR, and policymakers in several other countries, including the EU, Canada, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, DRC, Egypt, Iraq, Chile, and Brazil. His collaborative efforts span organizations such as the OECD, IEA, World Bank, UNCTAD, UNEP, OPEC, IRENA, and several philanthropic foundations.

Tom holds two master’s degrees and obtained his PhD at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva. This academic background includes fellowships at LSE and the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. He was also a Fulbright and Albert Gallatin Fellow, and a Swiss National Science Foundation Scholar.

In his downtime, Tom enjoys reading & writing, culinary experiences, football, skiing, and chess.

[i] Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025,” August 2025; International Energy Agency (IEA), “Global EV Outlook 2025,” May 14, 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025.

[ii] Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025,” August 2025.

[iii] IEA, “Global EV Outlook 2025,” May 14, 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025.

[iv] Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025”, August 2025.

[v] IEA, “Global EV Outlook 2025,” May 14, 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025.

[vi] Ibid.; Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025”, August, 2025.

[vii] Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025,” August 2025; California Air Resources Board, “Zero-Emission Vehicle Regulation,” n.d., https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/zero-emission-vehicle-program.

[viii] Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025,” August 2025.

[ix] IEA, “Global EV Outlook 2025,” May 14, 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

[xiii] IEA, “Global EV Outlook 2024: Trends in Electric Vehicle Batteries,” April 23, 2024, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/trends-in-electric-vehicle-batteries.

[xiv] Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

[xv] Rho Motion, “EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,” August 2025. This commentary draws on Rho Motion’s EV & Battery Forecast (Q2 2025) for regional projections of BEV and PHEV sales, battery demand, and technology trends. Rho Motion is an intelligence firm specializing in EV and battery markets whose granular, model-level forecasting is widely used by industry and policymakers. As with all proprietary market intelligence forecasters, not all of its underlying assumptions and methods are publicly disclosed, and long-term projections involve inherent uncertainty, particularly in markets without a clear policy direction, like the United States.

[xvi] Rho Motion, “EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,”August 2025.

[xvii] Bloomberg, “Electric Vehicles Make Up 11 Percent of US Car Sales,” October 16, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-10-16/1-in-10-us-car-sales-is-electric-but-future-is-uncertain-without-subsidies.

[xviii] Rho Motion, “EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,” August 2025.

[xix] Rho Motion, “Record Monthly EV Sales, Breaking the Two Million Mark,” October 15, 2024, https://rhomotion.com/membership-industry-updates/record-monthly-ev-sales-breaking-the-two-million-mark/.

[xx] Rho Motion, “EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,” August 2025.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] VDA, “10-Point Plan for Climate-Neutral Mobility: Reduce CO2 Emissions in Transport, Ensure the Competitiveness of the Automotive Industry,” June 5, 2025, https://www.vda.de/en/press/press-releases/2025/250606_PM_2030-2035_CO2-Flottenregulierung_EN.

[xxiii] ACEA, CLEPA, “The EU Risks Missing the Turn on Its Automotive Transition – September’s Strategic Dialogue Is the Change to Correct Course,” August 27, 2025, https://www.acea.auto/files/Joint-ACEA-CLEPA-letter-to-President-von-der-Leyen.pdf.

[xxiv] European Commission, “President von der Leyen Chairs Third Strategic Dialogue with the European Automotive Industry on 12 September,” September 10, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_2038.

[xxv] EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,” August 2025; Benchmark, “Chinese EV Brands Look to PHEVs to Avoid EU Tariffs,” May 2, 2025, https://source.benchmarkminerals.com/article/chinese-ev-brands-look-to-phevs-to-avoid-eu-tariffs; Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] IEA, “Global EV Outlook 2025,” May 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025.

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] Rho Motion, “EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,” August 2025; Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

[xxx] T&E, “Smoke Screen: The Growing PHEV Emissions Scandal,” October 16, 2025, https://www.transportenvironment.org/articles/smoke-screen-the-growing-phev-emissions-scandal.

[xxxi] Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

[xxxii] European Commission, “European Alternative Fuels Observatory: Portugal,” n.d., https://alternative-fuels-observatory.ec.europa.eu/transport-mode/road/portugal/incentives-legislations.

[xxxiii] Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

Remember the climate crisis? The relentless, escalating threat to human health and safety that was once the main driver of clean energy policy?

You’d be forgiven if it’s all a bit hazy, given how swiftly the term was dropped from the energy-transition lexicon this year.

Starting on Inauguration Day, President Donald Trump not only eviscerated climate policy but completely upended the way Americans talk about energy. Though Trump seemed more concerned with taking down ideological rivals than helping constituents’ bottom lines, his new lexicon got a boost from consumer concerns about soaring energy prices that had people casting around for quick fixes. Climate change was out. Talk of “energy dominance,” “energy abundance,” and “unleashing American energy” rushed in. The shift was like “6-7” taking over a fourth-grade classroom: inexorable and irresistible.

The new terminology made the scene on Trump’s first day back in the White House, when he signed an executive order with a grab bag of fossil-fuel giveaways under the title “Unleashing American Energy.” A few weeks later, he used another executive order to create the National Energy Dominance Council. Both orders touted the country’s “abundant” resources.

Clean energy advocates quickly began invoking similar terminology in an attempt to shoehorn solar power into the new narrative. The Solar Energy Industries Association even passed out stickers with the phrase “energy dominance” on Capitol Hill as part of its lobbying efforts.

Some media outlets followed suit in deemphasizing climate. In November 2024, five major U.S. newspapers published a total of 524 stories about climate change; in the same month this year, those papers ran just 362 climate change articles, according to researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder — a drop of almost a third. (Both numbers are way down from the October 2021 peak of 1,049 climate articles.)

A number of Democratic politicians embraced the vibe shift in their own ways. “All of the above” crept in among leaders — notably New York Gov. Kathy Hochul and Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey — who wanted to signal they are open to the changing conversation, but not ready to give up on renewables entirely. In New Jersey and Virginia, Democrats Mikie Sherrill and Abigail Spanberger ran successful gubernatorial campaigns with hardly any mention of climate change; likewise, New York City mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani spent little time on the topic.

Most notably, Democrats this year prioritized the issue of energy affordability, an increasingly urgent concern among voters — and one that Trump is belligerently dismissing.

Two liberal groups, Fossil Free Media and Data for Progress, put out a memo in November that endorses this affordability focus, suggesting it’s a way for Democrats to reconcile the new discourse with the old. The memo encourages them to promote the benefits of renewable energy as a cheap source of power in 2026. The headline: “Don’t run from climate — translate it.”

Though Republicans are failing to reckon with the issue of soaring energy costs, there’s still something seductive about their energy rhetoric. It suggests an economy teeming with possibility, held back only by those meanie Democrats with their snowflakey concerns about climate and their insufficient will to dominate. The language implies there are easy answers to at least some of our woes. Worried about soaring energy bills? Unleash the beautiful coal. Concerned about grid reliability? Exploit those abundant energy supplies. Never mind that fossil fuels are most definitely not the cheapest sources of electricity.

The vocab shift, particularly around “dominance,” also captures a vibe that has always appealed to Trump supporters: “That language does have this bravado and machismo that is important to his movement,” Cara Daggett, a professor of political science at Virginia Tech, told a reporter for Grist earlier this year.

What vocabulary will seize the collective imagination in 2026? Likely, more of the same (though Trump does have a seemingly inexhaustible ability to surprise us all with word choices). The bigger question for me, though, is which version of this new nomenclature will gain the most traction in the months to come. Will the left’s translations catch on, convincing people that clean energy too can be unleashed, abundant, and affordable? Or will the fossil fuel–loving MAGA crowd continue to corner the enticingly muscular language of supremacy?

When Donald Trump won the presidential election last November, it wasn’t totally clear how serious he was about dismantling offshore wind. Sure, he liked to rant about turbines making the whales crazy, and there was the infamous legal fight over a wind farm off the coast of his golf course in Scotland. But would he really try to cut down an entire energy sector? Did he even have the power to do so?

The answers, as we found out in this decisive and devastating year, are yes and pretty much.

On his first day in office, Trump issued an executive order that froze offshore wind permitting and ordered the Interior Department to review the projects it had already approved. The move immediately gummed up any developments that didn’t have federal permits, but the upshot was murkier for the nine projects with approvals in hand. (In mid-December, a federal court struck down that executive order.)

The first already-permitted undertaking to crumble was the Atlantic Shores installation in New Jersey. In late January, Shell — one of the two developers — announced it was pulling out. Then New Jersey backed away from buying power from the turbines. Weeks later came the sea salt in the wound: The Environmental Protection Agency revoked a Clean Air Act permit for Atlantic Shores.

Trump’s war on offshore wind escalated from there, threatening the viability of a reliable form of electricity even as the president declared an “energy emergency” in the United States.

The administration halted work on New York’s 810-megawatt Empire Wind 1 project in April; construction resumed after about a month and nearly $1 billion in costs for the developer. The budget law passed by Republicans in July killed tax credits for wind farms that don’t come online ASAP. The 704-megawatt Revolution Wind installation near Rhode Island got a stop-work order, too; that one was also lifted after about a month. The Transportation Department yanked funding for a bunch of infrastructure projects related to offshore wind in September. Then Trump told a half-dozen agencies to root around for reasons to oppose installing turbines out at sea.

Just for good measure, the administration is still trying — and sometimes failing — to revoke permits for approved but earlier-stage installations that would likely struggle to begin construction anyway, given the, uh, inhospitable climate.

The clearest way to understand the carnage is to look at the numbers.

When Trump was elected last November, BloombergNEF expected the U.S. to build 39 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2035. The research group hedged that number to 21.5 gigawatts if Trump managed to repeal wind tax credits during his term. (Reminder: He did.)

BNEF now expects just 6 gigawatts to be built by 2035 — an amount equivalent to the capacity of the five wind farms currently under construction, as well as America’s only completed large-scale project, New York’s South Fork. Should Trump’s late-December pause on all of these in-progress wind farms result in cancellations, the number will be even lower.

The energy source, long considered a cornerstone of grid-reliability and decarbonization plans in the Northeast, was already in a fragile place before Trump took office for the second time. Inflation and pandemic-era supply-chain thorniness had scrambled economics. Local opposition, both astroturfed and real, was on the rise. Major projects from major developers had already fallen apart.

Trump’s all-out war would have been difficult for any industry to survive. But for a nascent one that was already in deep water — and which is uniquely dependent on federal permitting — it was all but impossible.

The question now is whether the Trump 2.0 era will prove to be a four-year blip or the start of longer-term doldrums for the sector in America.

Five and a half months. That’s all the time Donald Trump needed to crush the only major climate law the United States ever managed to pass. It was swift work, using a sledgehammer and not a scalpel, and now the energy transition will have to make do with the fragments of the law that remain.

The words bleak and dispiriting come to mind. How else to describe the fact that the U.S. entered the year implementing an ambitious if inadequate decarbonization law, and is now exiting 2025 with that law all but repealed?

But there were also some reasons to be hopeful about the energy transition this year — if you knew where to look.

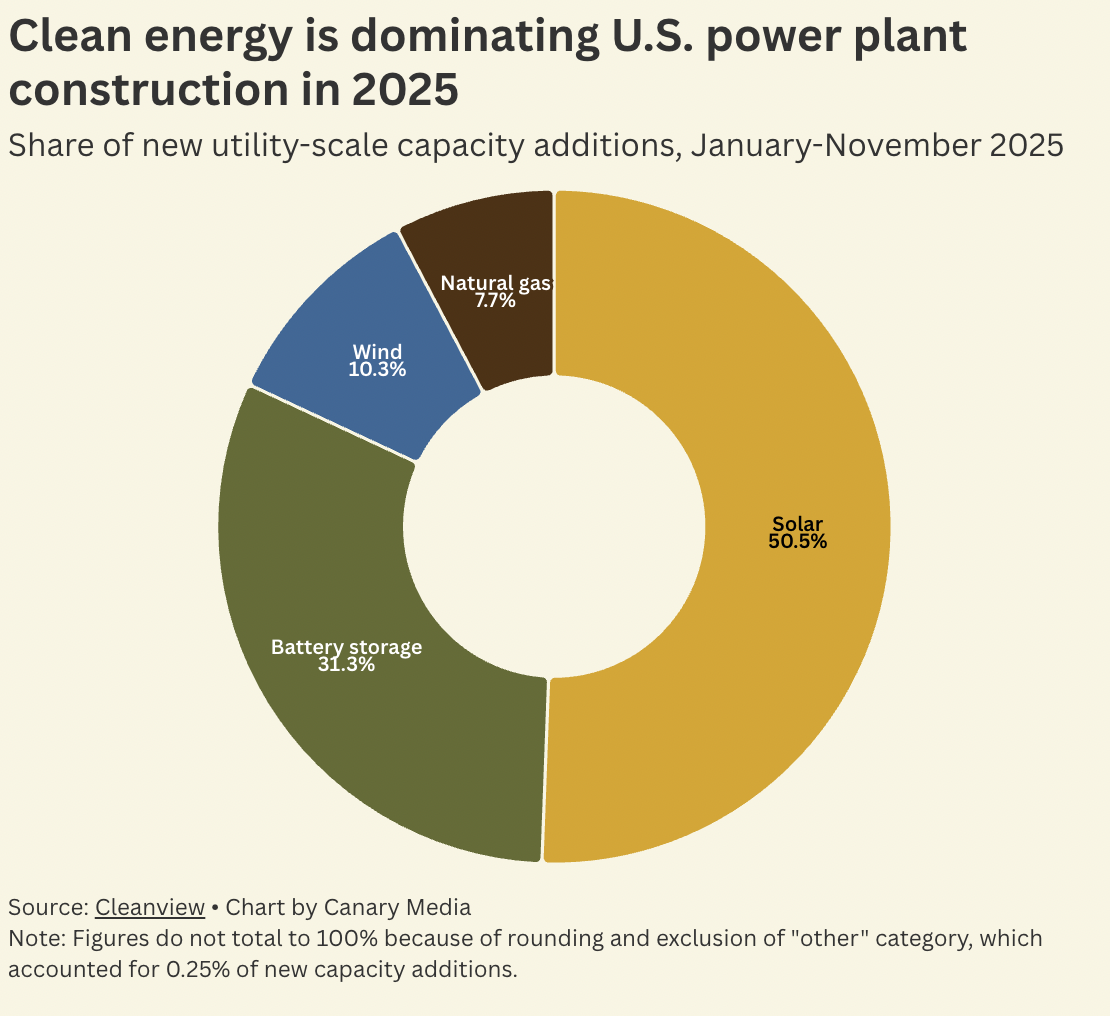

Let’s start with the numbers. During a year full of headline-grabbing destruction of U.S. clean energy policy, renewables still led the way. Through November, a whopping 92% of all new electricity capacity built in the U.S. came in the form of solar, batteries, and wind power. Electric vehicle sales hit a record, too — nearly 440,000 in the third quarter of the year — though the surge was driven in large part by consumers rushing to buy EVs before the disappearance of a federal tax credit axed by Trump.

There were also intriguing moments of alignment between Trump’s “energy dominance” agenda and the transition away from fossil fuels. Geothermal and nuclear are two sources of carbon-free energy that the administration has, for whatever reasons, deemed desirable. So while the One Big Beautiful Bill Act eviscerated much of President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, it spared tax credits for geothermal systems. And Trump has not only preserved Biden-era funding for nuclear projects but expanded it — possibly by orders of magnitude if an $80 billion plan for partially state-owned nuclear reactors actually happens.

The most important thing we saw this year is that Trump simply can’t stop the energy transition. Sure, he can slow it. He already has. But try as the administration might, there are forces at play bigger and more stubborn even than politics.

To be specific: Electricity demand is growing quickly in the U.S., and clean energy is the least expensive and most readily available way to keep pace.

The Trump administration would certainly prefer to meet rising demand with coal and gas, but in many cases it’s simply impractical.

Coal is increasingly the most expensive form of electricity. Gas, for better or for worse, certainly will help meet some of this new demand — but it faces very real supply-chain constraints. Gas turbines are sold out among major manufacturers, with wait times stretching as long as seven years.

When the country is clamoring for more electrons and voters are increasingly upset about rising power bills, and the only thing that can be built quickly is solar and storage, renewables will simply have to be built. (They’ll just cost more than they would have without Trump.)

So while it hasn’t been a good year for clean energy in the U.S., the transition now has enough momentum that even a terrible year amounts to more of a slowdown than a derailment. It’s a matter of inertia.

Those in the energy sector, like everyone else, could not stop talking about artificial intelligence this year. It seemed as if every week brought a new, higher forecast of just how much electricity the data centers that run AI models will need. Amid the deluge of discussion, an urgent question arose again and again: How can we prevent the computing boom from hurting consumers and the planet?

We’re not bidding 2025 farewell with a concrete answer, but we’re certainly closer to one than we were when the year started.

To catch you up: Tech giants are constructing a fleet of energy-gobbling data centers in a bid to expand AI and other computing tools. The build-out is encouraging U.S. utilities to invest beaucoup bucks in fossil-fueled power plants and has already raised household electricity bills in some regions. Complicating things further is that many of today’s proposed data centers may never get built, which would leave the rest of us to foot the bill for expensive and unnecessary power plants that bake the planet.

It’s all hands on deck to find solutions. Lawmakers across every state considered a total of 238 bills related to data centers in 2025 — and a whopping half of that legislation was dedicated to addressing energy concerns, according to government relations firm MultiState.

Meanwhile, the people who operate and regulate our electric grid worked on rules to get data centers online fast without breaking the system. One idea in particular gained traction: Let the facilities connect only if they agree to pull less power from the grid during times of über-high demand. That could entail literally computing less, or outfitting data centers with on-site generators or batteries that kick in during these moments.

Even the Trump administration got in on the action, with Energy Secretary Chris Wright directing federal regulators in October to come up with rules that would let data centers connect to the grid sooner if they agree to be flexible in their power use. But this idea of “load flexibility” is still largely untested and has its skeptics, who argue that it’s technically unrealistic under current energy-market frameworks.

And then there are the hyperscalers themselves. Big tech companies with ambitious climate goals are signing power purchase agreements left and right for energy sources from geothermal to nuclear to hydropower. Google unveiled deals with two utilities this summer to dial down data centers’ power use during high demand. Texas-based developer Aligned Data Centers announced this fall that it would pay for a big battery alongside a computing facility it’s building in the Pacific Northwest, allowing the servers to get up and running way faster than if the company waited for traditional utility upgrades.

Expect more action on this front in 2026. Local opposition to data centers is on the rise, power-demand projections are still climbing, and speculation is mounting that the entire AI sector fueling those forecasts is a big old bubble about to pop.

This story was originally published by Grist. Sign up for Grist’s weekly newsletter here.

President Donald Trump spent most of 2025 hacking away at large parts of the federal government. His administration fired, bought out, or otherwise ousted hundreds of thousands of federal employees. Entire agencies were gutted. By so many metrics, this year in politics has been defined more by what has been cut away than by what’s been added on.

One tiny corner of regulation, however, has actually grown under Trump: the critical minerals list. Most people likely hadn’t heard of “critical minerals” until early this year when the president repeatedly inserted the phrase into his statements, turning the once obscure policy realm into a household phrase. In November, the U.S. Geological Survey quietly expanded the list from 50 to 60 items, adding copper, silver, uranium, and even metallurgical coal to the list. In mid-December, South Korean metal processor Korea Zinc announced that the federal government is investing in a new $7.4 billion zinc refinery in Tennessee, in which the Department of Defense will hold a stake.

But what even is a critical mineral?

The concept dates back to the first half of the 20th century, especially World War II, when Congress passed legislation aimed at stockpiling materials vital to the United States’ well-being. President Trump established the critical minerals list in 2018, with the defining criteria being that any mineral included be “essential to the economic and national security of the United States” and have a supply chain that is “vulnerable to disruption.” A mineral’s presence on the list can convey a slew of benefits to anyone trying to extract or produce that mineral in the U.S., including faster permitting for extraction, tax incentives, or federal funding.

As Grist explored in its recent mining issue, critical minerals are shaping everything from geopolitics to water supplies, oceans, and recycling systems. If there is to be a true clean energy transition, these elements are key to it. Metals such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel form the backbone of the batteries that power electric vehicles. Silicon is the primary component of solar cells, and rare earth magnets help wind turbines function. Not to mention computers, microchips, and the multitude of other things that depend on critical minerals.

Currently, the vast majority of critical minerals used in the United States come from China — some 80%. In his first term, Trump tried to increase domestic production of these minerals. “The United States must not remain reliant on foreign competitors like Russia and China for the critical minerals needed to keep our economy strong and our country safe,” he said in 2017. Securing a domestic supply was also a cornerstone of former President Joe Biden’s landmark climate bills, the bipartisan infrastructure law and the Inflation Reduction Act.

Now, as Trump has taken office again, he’s made critical minerals an ever more central part of his policy platform. We’re here to demystify why this has been a blockbuster year for critical minerals in the United States — and where the industry may go in the future.

In March, Trump issued an executive order meant to jump-start critical mineral production. “It is imperative for our national security that the United States take immediate action to facilitate domestic mineral production to the maximum possible extent,” he said. The executive order was just the first step in a coordinated effort by the Trump administration to strengthen U.S. control over existing supply chains for copper, lithium, cobalt, manganese, nickel, and dozens of other critical minerals and to galvanize new mines, regardless of concerns raised by Indigenous peoples. The Trump administration has sought to accomplish these goals by both reducing the regulatory barriers to production and by investing in the companies poised to do it.

Since then, Trump has signed agreements with multiple countries to increase investments in critical minerals and strengthen supply chains. Most recently, the U.S. made a deal with the Democratic Republic of Congo, which holds more than 70% of the world’s cobalt. He has pushed federal agencies to make it easier for mining companies to apply for federal funding, and is inviting companies to apply to pursue seabed mining in the deep waters around American Samoa, near Guam and the Northern Marianas, around the Cook Islands, and in international waters south of Hawaii — prompting global outrage and opposition from Native Hawaiian, Samoan, and Chamorro/CHamoru peoples. At the same time, Trump’s volatile tariff policies have made it harder for American companies to source minerals, and cuts to federal funding have harmed mining workforce training programs and research into critical minerals.

While the Biden administration provided grants and loans to various mining companies, Trump is deploying a highly unusual strategy of buying stakes in private companies, tying the financial interests of the U.S. government with the interests and success of these commercial mining operations. Over the past few months, the Trump administration has spent more than a billion dollars in public money to buy minority stakes in private companies like MP Materials, ReElement Technologies, and Vulcan Elements. In Alaska, that strategy has involved investing more than $35 million in Trilogy Metals to buy a 10% stake in the company, which is a major backer of a copper and cobalt mining project in Alaska.

In September, the Trump administration finalized another deal with the Canadian company Lithium Americas behind Thacker Pass in Nevada, which is expected to be the largest lithium mine in the U.S. The Biden administration approved a $2.23 billion loan to Lithium Americas in October 2024; the Trump administration then restructured the loan and obtained a 5% stake in the project and another 5% stake in Lithium Americas itself. (A top Interior Department official has since been reported to have benefited financially from the project.) That’s despite allegations that the mine violates the rights of neighboring tribal nations and is proceeding without their consent, which Lithium Americas has denied.

Historically, the federal government has only taken equity stakes in struggling companies, such as through the Troubled Asset Relief Program that sought to stabilize the auto industry and U.S. banks during the 2008 financial crisis. “What we’re talking about here is something very different, which is an industry that has not yet launched,” said Beia Spiller, who leads critical minerals work at the nonprofit research group Resources for the Future.

“Whether that’s going to work, I think is unlikely,” Spiller continued. “The best way to get an industry up and running is to have policies that raise the tide for everyone, not just choosing winners.”

In reference to Lithium Americas, Spiller said, “If you actually look at the cost fundamentals, it’s not a very competitive company.” Lithium Americas mines metal from clay, an old process that requires a lot of land, open pit mines, and heavy machinery — whereas some newer operations use direct lithium extraction, which is more cost-effective in the long term. “So we just took an equity stake in a company that is going to face headwinds in terms of costs — now the American public faces that downside.”

It must also be stressed that the Trump administration’s rapid push to shore up the U.S.’s control over critical minerals isn’t about transitioning the country away from fossil fuels. Instead, the whole effort seems to mostly be geared toward military uses. Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act allocated $7.5 billion for critical minerals, $2 billion of which will go directly to the national defense stockpile. Another $5 billion was allocated for the Department of Defense to invest in critical mineral supply chains.

In October, a former official at the Defense Department told the Financial Times that the agency is “incredibly focused on the stockpile.”

“They’re definitely looking for more, and they’re doing it in a deliberate and expansive way, and looking for new sources of different ores needed for defense products,” the unnamed official said.

The administration recently announced that it plans to take equity stakes in more mining companies next year. It’s possible, Spiller said, these investments could extend to outfits that are piloting deep-sea mining. That carries a new set of risks, as many banks refuse to insure deep-sea mining operations, it’s unclear whether seabed mining operations will be able to even get off the ground before the end of Trump’s term, and the legal repercussions associated with undermining the Law of the Sea could fracture the stability among global powers — and make global climate action that much harder.

It’s been a rollercoaster of a year for clean energy. There’s no better way to show those ups and downs than with a chart, and luckily, we made a lot of those this year.

As 2025 comes to a close, let’s focus on just the ups. Here are 10 charts that prove the clean energy transition is still marching on in the U.S. and beyond.

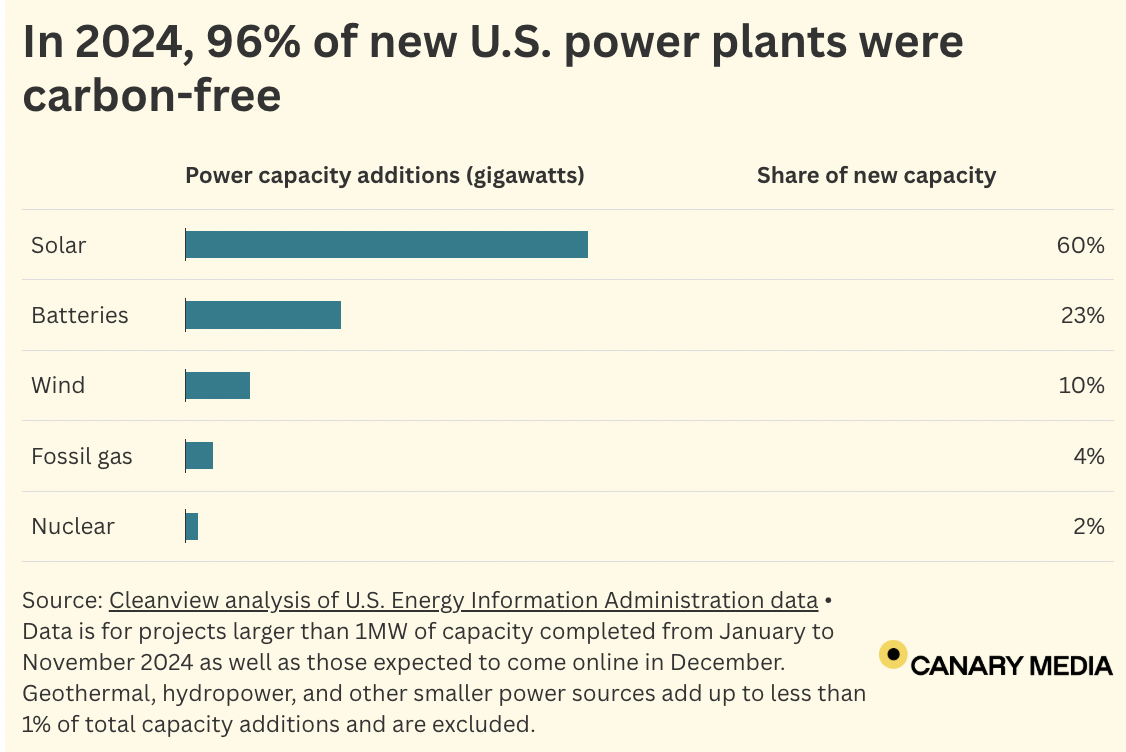

We started 2025 with news of a big win from the year before. The U.S. added 56 gigawatts of power capacity to the grid in 2024, and nearly all of it came from solar, battery, wind, nuclear, and other carbon-free installations.

Solar, with 34 GW of new construction, made up more than half of the new additions. Batteries had a stellar year, too, nearly doubling the previous year’s total.

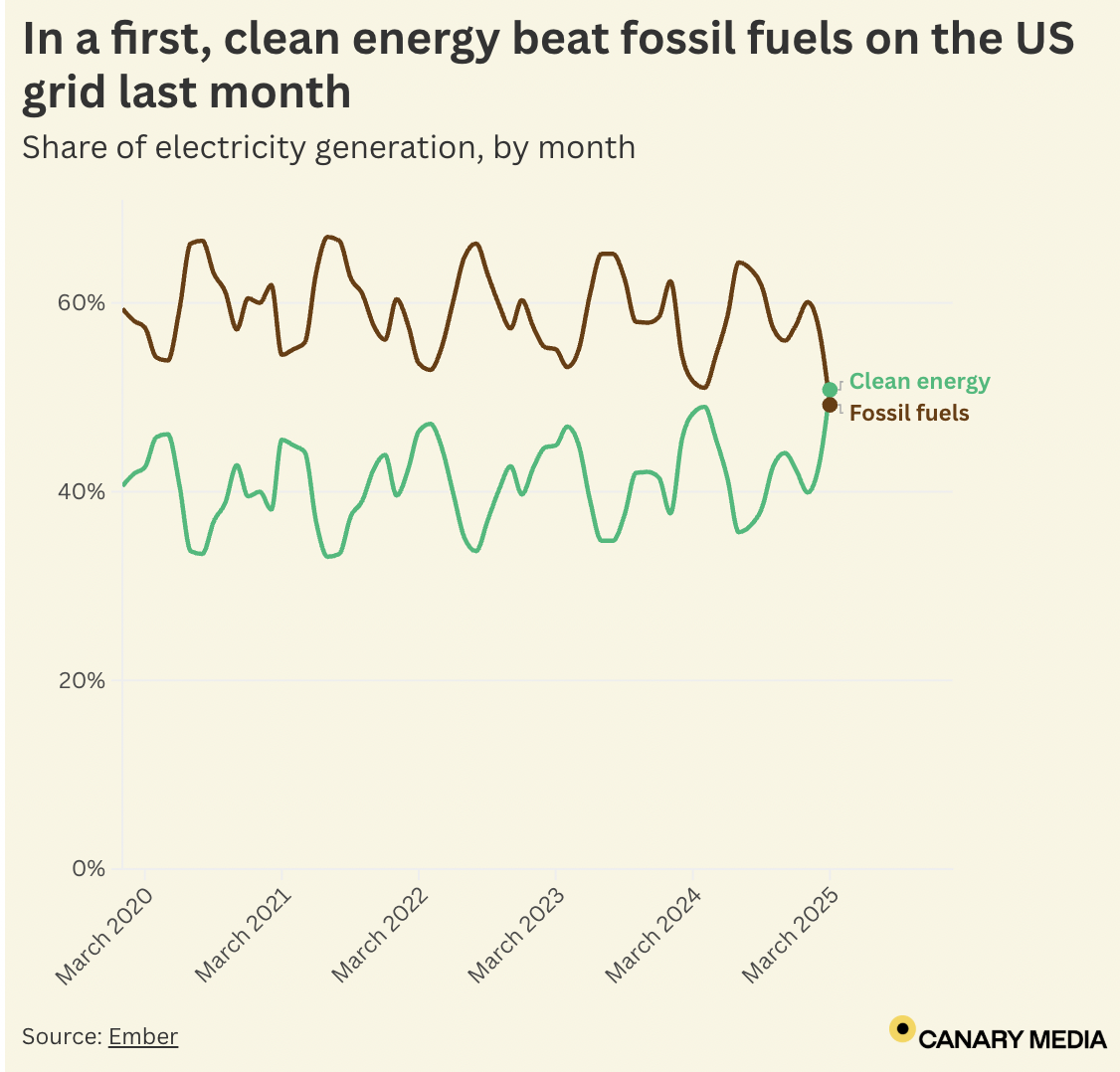

March brought a huge victory for clean energy in the U.S. Solar, hydropower, biofuels, and nuclear were all part of a clean team that covered 51% of electric power demand that month, while fossil fuels accounted for the remainder.

It’s not a surprise that this win came when it did. Milder temperatures that arrive with spring mean Americans are starting to switch off their heat, but don’t yet need air-conditioning, creating a low-demand “shoulder season.” Still, this chart shows how quickly the U.S. has closed a yawning gap between clean and fossil fuel power generation.

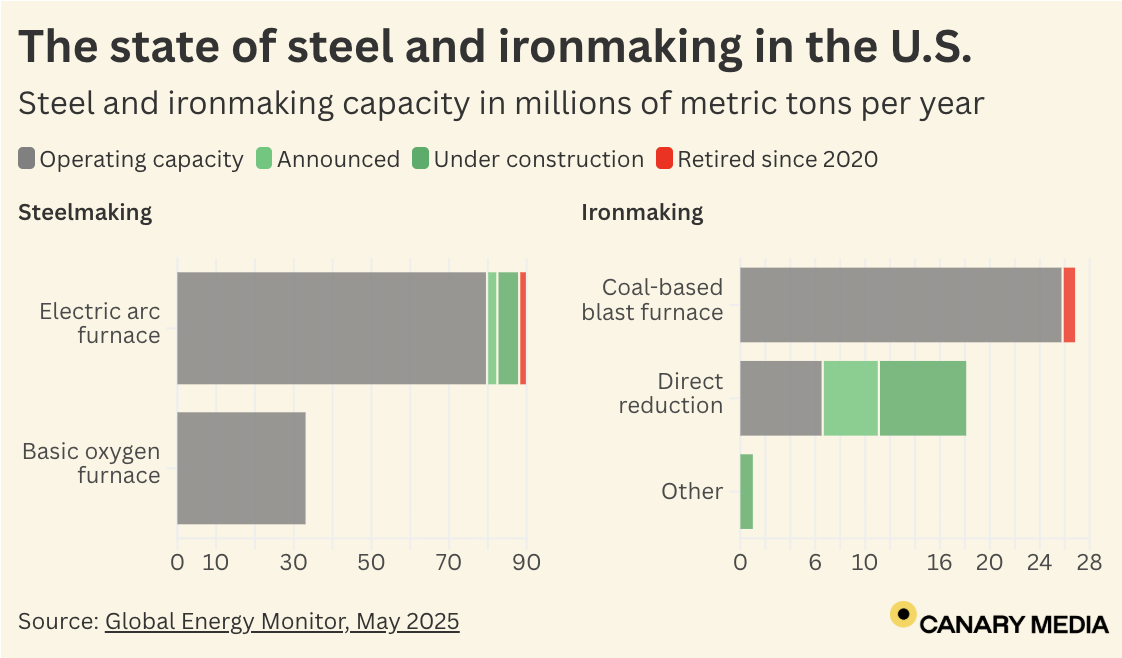

The U.S.’s steel and ironmakers are recording slow but steady progress toward getting off coal.

Steelmaking’s reliance on coal makes it one of the world’s dirtiest industries, but all new capacity in the works as of May will use technologies that sidestep the need to burn the fossil fuel. That includes several electric arc furnaces capable of producing millions of metric tons of steel each year.

The U.S. does still rely heavily on coal-fired blast furnaces to purify iron ore. But forthcoming projects will all use direct reduction, which uses natural gas as a fuel — and ironmakers could eventually replace that gas with carbon-free hydrogen.

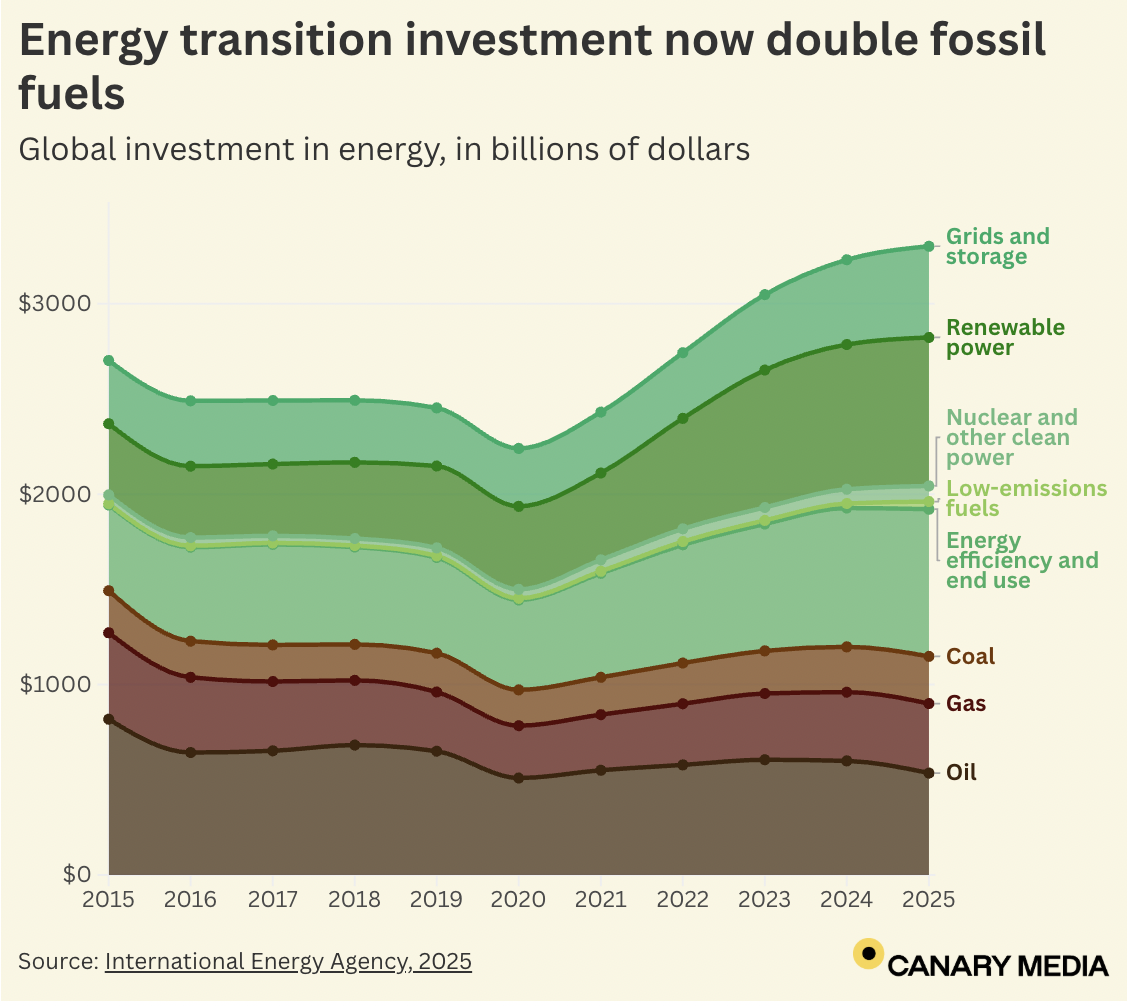

As of mid-year, the world was on track to spend $2.2 trillion on renewable power, low-emission fuels, the power grid, and other clean energy sectors. Fossil fuels were on track to reap half of that: $1.1 trillion.

It’s a big shift from a decade ago, when coal, gas, and oil investments dominated energy spending. But with China leading the way, clean investments have surged.

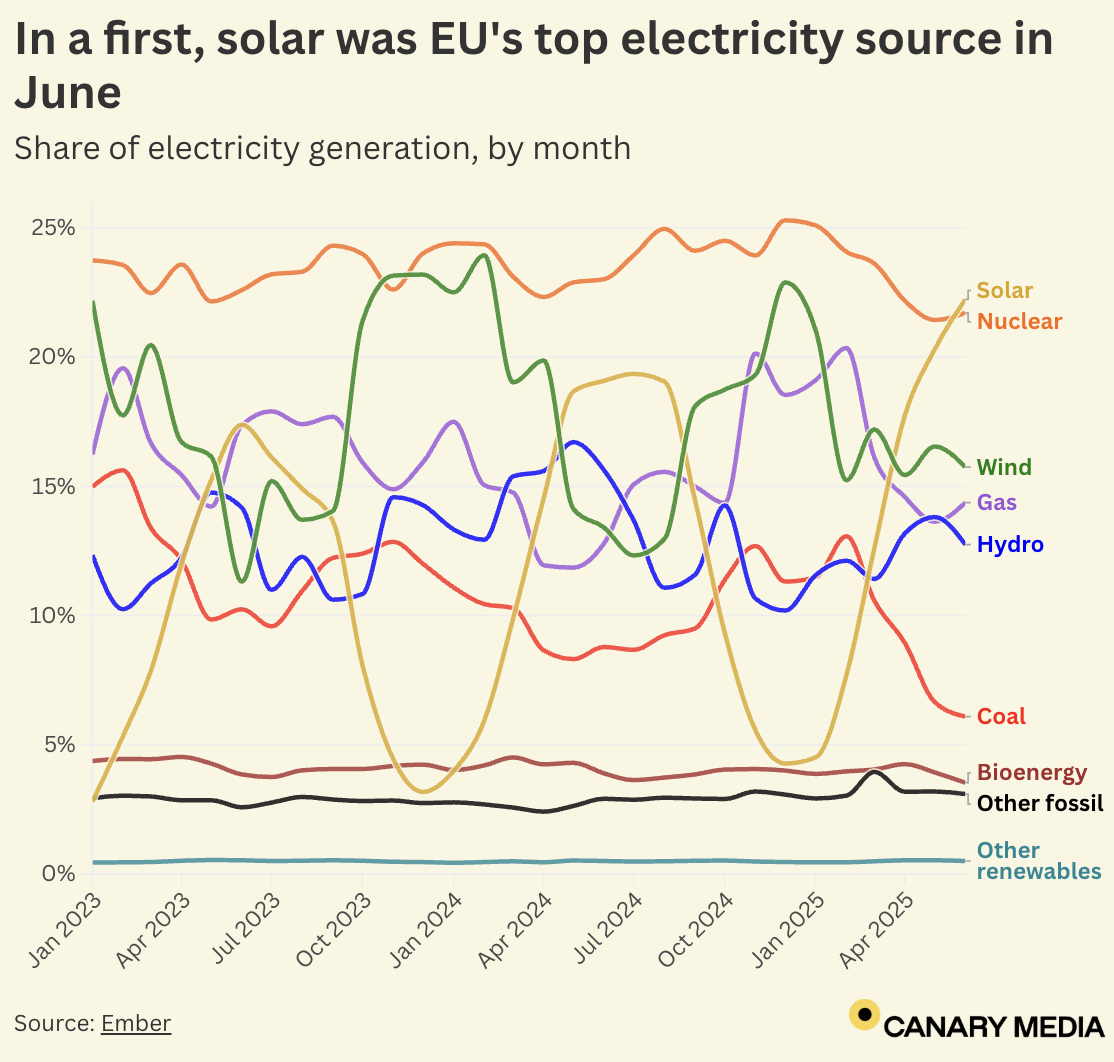

Europe had a squeaky clean June. For the first time ever, solar provided more of the EU’s power than any other source, beating both gas and coal power combined. Solar power provided 22.2% of the region’s electricity, with nuclear at its heels, and wind also beating gas generation.

Just a decade ago, coal provided a quarter of the EU’s power, while solar generated just a sliver. Now, those electricity sources are on track to trade places.

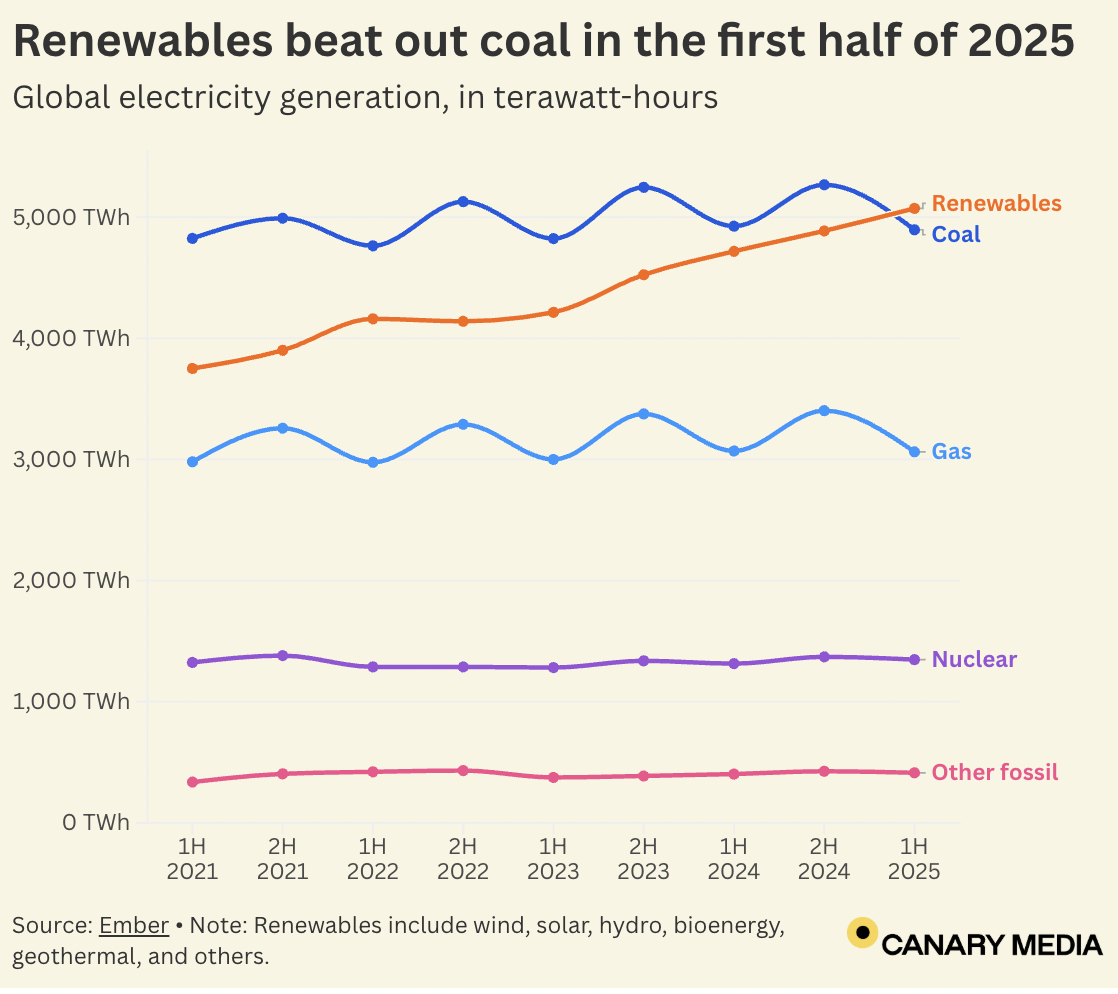

The first half of 2025 produced a worldwide win for renewables. January through July was the first time in history that renewables produced more power than coal over that stretch.

Solar’s monumental rise is the main reason for the shift: The source more than doubled its share of global electricity production from 2021 to 2025. And while coal still remains the world’s largest source of electricity, it’s declining while solar and other renewable sources are on the rise.

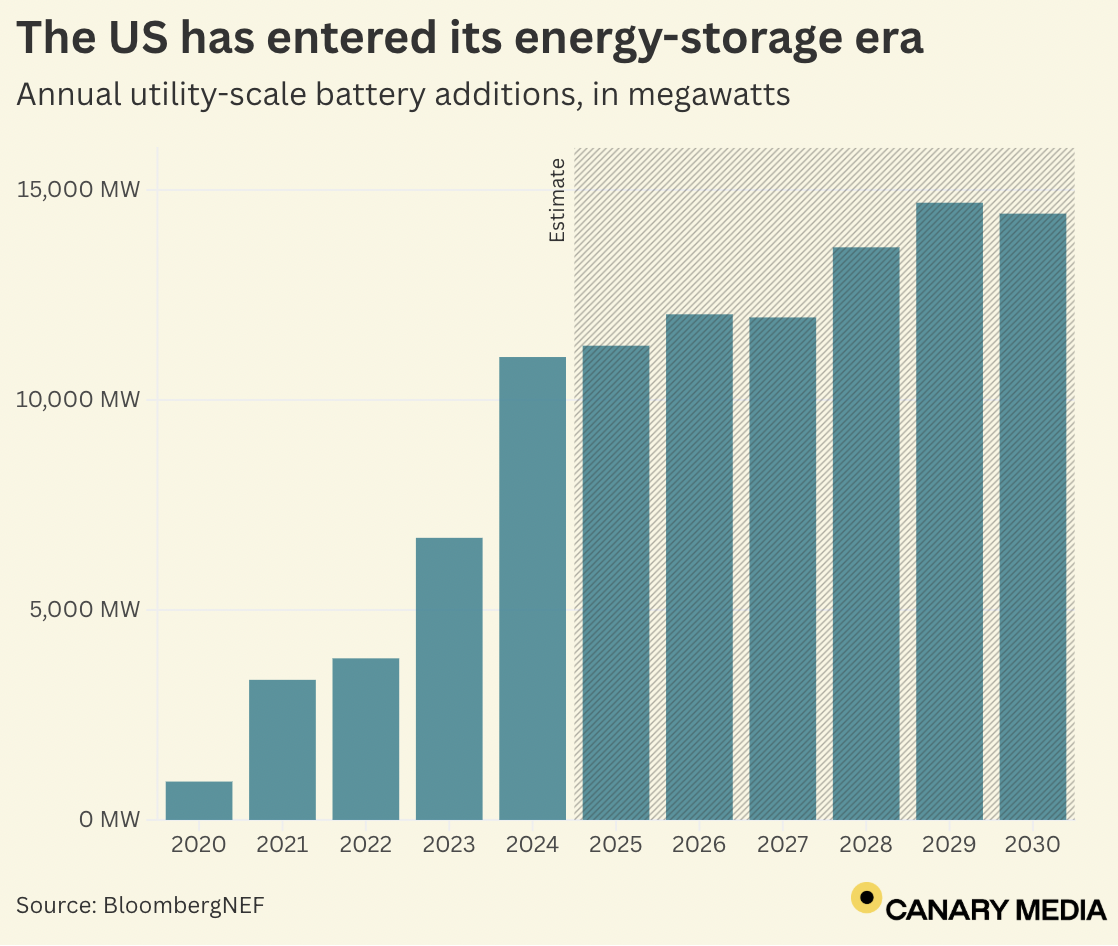

U.S. battery storage deployment has skyrocketed over the past five years, and that progress isn’t stopping anytime soon. Over the next five years, the country will build nearly 67 gigawatts’ worth of new utility-scale batteries, BloombergNEF estimates.

If that comes to fruition, the U.S. will have nearly triple the battery storage capacity it does now. And there’s evidence to suggest it will: The One Big Beautiful Bill largely left utility-scale battery storage incentives intact, for starters.

Energy storage is crucial for renewables to take root, as batteries can store solar and wind power for use when the sun isn’t shining and wind isn’t blowing.

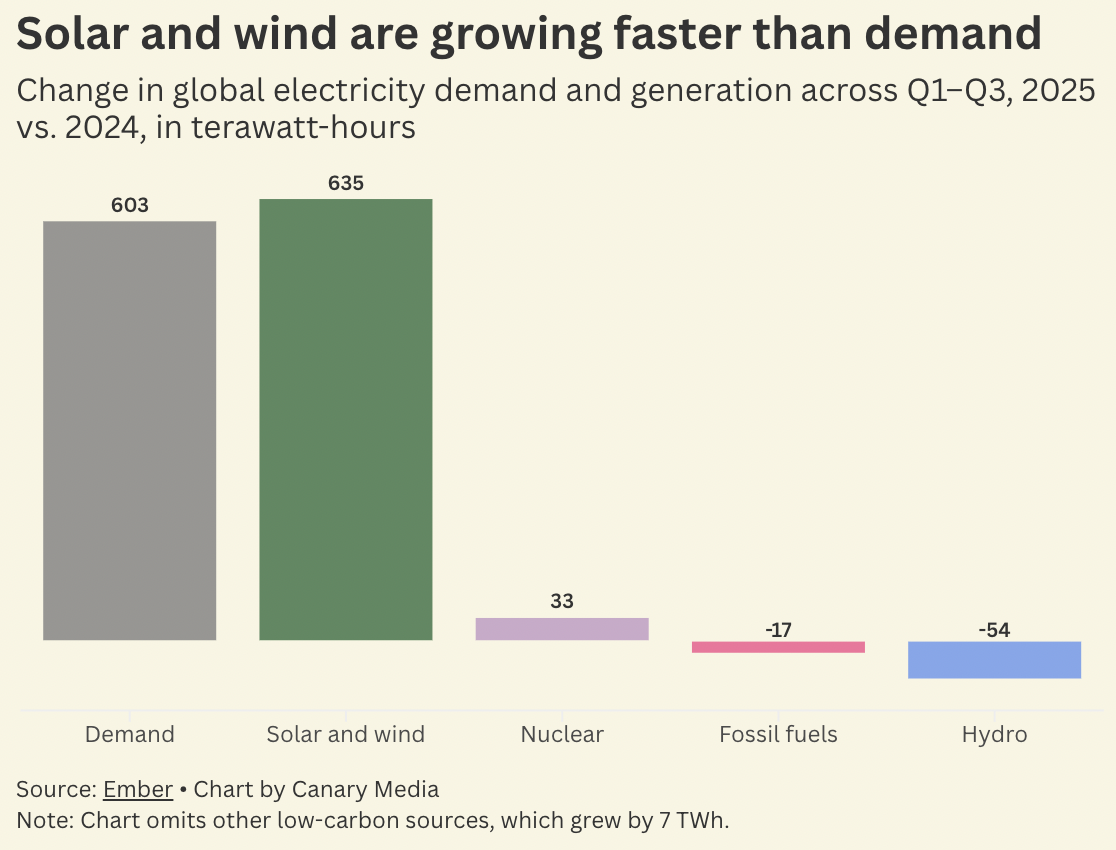

The latest data shows solar and wind made a speedy ascent this year — so speedy that they’re more than covering new power demand around the world.

Between January and September, power demand around the world rose by 603 terawatt-hours compared to that same time period last year. Solar met nearly all of that new demand on its own, and with a boost from wind, was able to cover all of it.

That’s a huge deal for the clean energy transition. When we produce more renewable power than is needed to cover growing demand, that’s when we can start chipping away at fossil fuels.

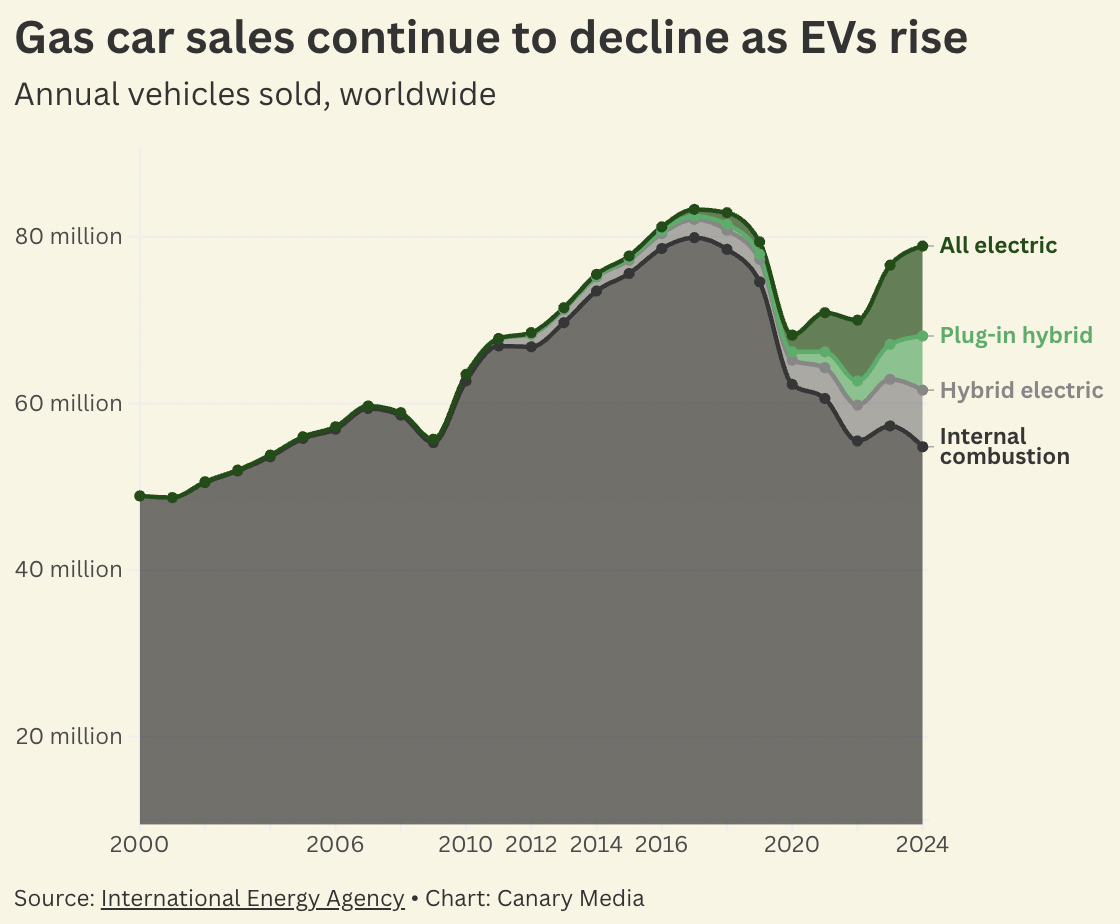

EVs may have faced a year of setbacks in the U.S. and beyond, but they’re still on an upward trajectory worldwide. Nearly 11 million new EVs were sold around the globe last year, with most of those new EVs hitting the road in China. Sales of plug-in hybrids and hybrid electric cars are on the rise too. Compare that to 15 years ago, EVs and hybrids were practically nonexistent.

Meanwhile, internal combustion vehicles are officially past their peak. At their all-time high in 2017, global sales of pure ICE vehicles hit 79.9 million units. Last year, sales dropped to 54.8 million.

Our final chart of the year is the ultimate bright spot. While the vibes suggested this would be a dismal year for clean energy deployment in the U.S., it simply wasn’t. Solar, wind, and storage accounted for 92% of new power capacity added to the grid this year through November. It all goes to show that while fossil fuels still produce most of the country’s electricity, clean energy’s growth is hard to stop.

For press releases, policy changes, and promises to build new nuclear power, 2025 was a gangbusters year. For actually adding new reactors to the grid, not so much.

In fact, around the world, more gigawatts’ worth of nuclear reactors were retired than turned on this year, according to new data from the consultancy BloombergNEF.

In the 11 months leading up to Dec. 1, only two new reactors came online, totaling 1.8 GW. Meanwhile, seven reactors totaling 2.8 GW of capacity were permanently shuttered. The net effect? Global nuclear operating capacity declined by just over 1 GW. Overall, the world had 417 reactors in operation churning out 337 GW of power as of the start of this month.

Belgium led the retreat, shuttering two reactors this year, even as the country’s lawmakers voted in May to repeal a 2003 law that required the country to phase out nuclear power entirely.

Taiwan also contributed to the decline when it closed the last reactor at its Maanshan plant on the island’s southern tip, completing the country’s long-awaited exit from atomic energy. Russia will round out the closures by decommissioning three 12-megawatt units at a plant in the Arctic by the end of this month.

The shutdowns are the result of a yearslong pullback on nuclear power across much of the world, with China and Russia being the key exceptions.

But they also come at what may be a turning point for that global retreat from nuclear. Around the world, new technologies are racing toward maturity, shuttered reactors are being revived, and dealmakers are seeking to shore up the future supply of clean electricity by investing in new nuclear power. Next year is the first time in at least 15 years that zero reactors worldwide are slated to shut down. While closures will pick up again in 2027, new capacity is projected to dramatically outpace shutdowns through 2029.

The West and its allies have struggled to build and maintain reactors, and recent developments affecting South Korea, one of the more efficient nuclear developers, will not make matters easier.

The country’s state-owned nuclear companies have managed to avoid the sluggish build-outs that have plagued other developers. In June, however, South Korean voters returned to power the center-left Democratic Party, which tried to phase out the industry entirely the last time it held the Blue House. Further, an intellectual-property dispute between the American nuclear champion Westinghouse and Korea’s state-owned companies — Korea Electric Power Corp. and its subsidiary Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power Co. — came to a close this year with a settlement that bars Seoul’s firms from competing for projects in North America, most of the European Union, Britain, Japan, and Ukraine.

On top of that, according to Chris Gadomski, the lead nuclear analyst at BloombergNEF, “there’s a lot of hesitation among countries in the world to do business with the Chinese,” who are currently building reactors at a far faster rate than any other country.

That makes President Donald Trump’s efforts to revive nuclear construction at home and sell more reactors abroad particularly impactful for the industry’s future in the West and among its allies, especially countries in Africa and Asia building nuclear plants for the first time.

“The No. 1 question is how effective Trump’s pushing and shoving will be,” said Gadomski, who authored the market overview report published last week. “He’s really trying to reestablish American nuclear dominance.”

Unlike buying solar panels or batteries from China, nuclear reactors are century-long commitments between the construction, operation, and eventual decommissioning of the plant. Each of those steps is traditionally carried out by the vendor country.

“People are just concerned, so there is an opening for U.S. technology to be exported overseas,” Gadomski said. “People are dying to get U.S. technology.”

But right now, he warned, the small modular reactors attracting most of the attention have yet to be proven. And the only new reactor the U.S. has built from scratch on its own turf since the 1990s is the Westinghouse AP1000 at Southern Co.’s Alvin W. Vogtle Electric Generating Plant in Georgia. The two new units there ran billions of dollars over budget.

Estimates from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggest that the next AP1000 will come in significantly cheaper than even the shrunken-down small modular reactors currently under consideration, since the supply chain and design are now cemented. Indeed, Vogtle Unit 4 came in roughly 30% cheaper than Vogtle Unit 3, the first AP1000 to be built in the U.S.

Washington is working to expand the AP1000’s footprint. Both the Export-Import Bank of the U.S. and the U.S. International Development Finance Corp. have expressed interest in financing the construction of Poland’s first nuclear plant, made up of three AP1000s. In October, the Department of Commerce announced a deal with Japan to furnish Westinghouse with at least $80 billion to build 10 AP1000s in the U.S.

But Gadomski cautioned that the willingness to make such big investments largely hinges on the rising demand for power from data centers providing artificial intelligence software.

“If the AI boom collapses, we won’t need so much energy,” he said. “We’ve got tons of cheap natural gas, and there are technical and social risks to building out nuclear.”

Two years ago, Massachusetts regulators created a framework for phasing out the use of natural gas in buildings — a groundbreaking move for the state’s decarbonization efforts. Today, however, momentum has slowed as gas companies clash with lawmakers, regulators, and advocates on a fundamental question: Are utilities legally obligated to provide gas service to any consumer who wants it?

The debate may seem arcane, but at stake is the speed and scope of Massachusetts’ clean energy transition — and one of the nation’s first major attempts at a managed shift away from gas.

National Grid, Eversource, and other gas utilities say the answer is a resounding yes. The ability of residents and businesses to choose gas service is a “fundamental right,” said Eversource spokesperson Olessa Stepanova: “We cannot force them off that service.”

On the other side of the argument, advocates contend that safeguarding public health and fighting climate change are urgent benefits that outweigh individual customers’ personal preferences for one kind of fuel. The obligation, in their view, is to provide functional heating — not a specific source. The utilities, they say, are looking for ways to delay an inevitable upheaval in their industry rather than collaborating on a smooth transition.

“They see this as an existential threat to their business model, and they are digging in. They’re not at the table,” said James Van Nostrand, who chaired the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities when it issued the 2023 order, and who is now policy director at The Future of Heat Initiative.

Massachusetts has long been a leader in pushing for a transition away from using natural gas and other fossil fuels to heat buildings and to fuel stoves and dryers.

In October 2020, the state was one of the first in the nation to launch a “Future of Gas” investigation, a process examining how gas companies can play a role in the clean energy transition and what that should look like. In December 2023, the state Department of Public Utilities wrapped up the investigation with a 137-page report that spelled out a clear vision of stopping the expansion of gas service and decommissioning some portions of the infrastructure, but largely left it to lawmakers, regulators, and utilities to enact the principles outlined.

The future laid out in the document goes like this: Rather than automatically investing in new gas infrastructure or replacing aging pipes, utilities will look for opportunities to deploy “non-gas pipeline alternatives” — like geothermal networks, air-source heat pumps, energy efficiency, or demand response — that can meet customers’ needs. Gas utilities will proactively coordinate with electric utilities to ensure the poles and wires can accommodate, say, switching dozens of houses in an area to heat pumps. The order also calls for utilities to undertake demonstration projects to test out the process of transitioning neighborhood-scale portions of the gas system to electrified heat or thermal networks.

The order called for gas utilities to submit plans detailing how they would assess whether an area could be equally or better served by a non-gas option. They did so in April 2025, but there is a catch: Utilities insist that they need customers to agree to participate in any such alternatives.

“It’s very hard to accomplish any decommissioning if you have to have that 100% buy-in from all the customers,” Van Nostrand said.

At the heart of the utilities’ argument is the legal concept of “obligation to serve.” The idea, a common principle in utilities regulation, is that a gas utility can’t just cut off customers it is already serving; if you want to keep gas, you get to. Requiring customers to modify their equipment would infringe on their constitutional property rights, the gas utilities argue.

The Mass Coalition for Sustainable Energy, a coalition of business groups, labor unions, and professional associations, has its own concerns about accelerating a transition away from natural gas. The group argues that pushing customers from gas to electric heat could increase energy bills and possibly compromise grid reliability.

Advocates, however, say the utilities are seizing on the idea of obligation to serve to justify dragging their feet on a transition they don’t want to see happen.

“If policymakers are trying to do something utilities don’t like, delay is always a tool they will use to resist it,” said Caitlin Peale Sloan, vice president for Massachusetts at the Conservation Law Foundation.

What’s more, according to advocates, lawmakers, and the state attorney general’s office, is that the utilities are wrong on the law. They argue that utilities are allowed to withdraw gas service in certain circumstances, such as lack of payment or for reasons of health, safety, and other purposes defined in law. A climate law passed in 2024, they say, provides such a definition by specifically identifying the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions as a factor that may be considered when deciding whether gas service can be discontinued. It also specifies that regulators must consider whether “adequate substitutes” are available for heating and cooking.

Furthermore, the utilities’ argument about the importance of consumer choice ignores the fact that their position takes away choice from the households who would want to join a geothermal network, said Amy Boyd Rabin, vice president of policy and regulatory affairs for the Environmental League of Massachusetts.

“I want customers to be able to move into the future and not be weighted down by having to continue to pay for a fossil fuel infrastructure that they didn’t ask for and they don’t want,” she said.

The Department of Public Utilities is currently in the process of asking utilities for more details about their arguments and considering feedback from other stakeholders. Advocates expect that regulators will ultimately disagree with utilities’ understanding of the obligation to serve, sending the question to court.

Though Massachusetts was among the first to start formally planning a transition off gas, the utilities’ resistance means the process is moving too slowly, advocates said. And substantial progress is unlikely to occur until the question of what obligation to serve really entails is settled.

“That’s a very important legal question that underpins any attempt to move forward in a meaningful way on gas transition,” Peale Sloan said.

Kansas ranks among the sunniest states in the nation, and its famously flat landscape is ideal for vast rows of solar panels. Yet it ranks just 41st for solar installations, raising the question: What’s the matter with Kansas?

The simple answer is that on the gusty Great Plains, wind energy gained an early foothold and dominated the renewable buildout. The wonkier explanation points to the state’s weak incentives — including a voluntary renewable energy portfolio standard and a limited net-metering rule — as well as pushback from residents who don’t want to live next to solar arrays. As a result, the state has few utility-scale solar installations.

The developer of a 270-megawatt project in the northwestern corner of Kansas thinks the Sunflower State’s solar industry is poised to bloom.

Last week, Doral Renewables announced a power-purchase agreement for its Lambs Draw Solar project in rural Decatur County, bordering Nebraska. The company declined to disclose its offtaker, but CEO Nick Cohen said, “It’s a major tech company with a big name that does a lot of data centers across the U.S.”

“This is a turning point,” Cohen said. “You’re going to see more and more solar in places like Kansas.”

As recently as five years ago, he said, “it would have been wind.” But the best tracts of land for building turbines have already been developed.

The data indicates that a solar boom is indeed getting underway in Kansas — one in which Lambs Draw will be a key participant but far from the only one. In May, the state plugged in its first major project in the 189 MW Pixley Solar Energy installation, a big leap from the state’s second-biggest array of just 20 MW. Several even larger projects are expected to come online over the next few years, including a sprawling 510 MW installation slated to go live next December.

Construction hasn’t yet begun on Lambs Draw, but Cohen said the site is “shovel ready” and expects the project to benefit from safe-harbor rules that allow developers to lock in expiring federal investment tax credits by breaking ground early next year.

“What has happened is that solar has become the lowest levelized cost of energy of any new-build energy source out there,” Cohen said. “Solar has reached the tipping point where it’s the most economical and achievable energy solution in places like Kansas.”

Lambs Draw will span 4,000 acres leased from four landowners, though not all of it will host panels. Part of Doral Renewables’ strategy is to “use avoidance and what I call neighborly courtesy,” Cohen said. That means “getting more land than we need, then avoiding any sort of environmental features, whether it’s a habitat or wetlands.”

Then, he said, “we’ll ask neighbors, ‘Is it OK if we put this here?’”

The local acceptance matters. At this point, solar development is “not really a question of state by state anymore,” said Pol Lezcano, the director of energy and renewables research at the real estate and consulting firm CBRE.

“It’s more like a county-by-county issue,” he said.

The economic development agency in Decatur County lured Doral to the region in hopes of generating more tax income and finding a way for farmers to diversify revenue.

“They respect landowner rights as sacred,” Cohen said. “The officials in the county are also very professional and see this as a generational uplift for everyone. They’ve been incredibly friendly. They convinced us to come, and it worked.”

Part of Doral’s appeal was that Lambs Draw may, in fact, involve lambs. The company plans to incorporate agrivoltaics, with crops planted between rows of panels and livestock employed to graze and keep the grasses trimmed. Cohen said the company and its landlords haven’t yet decided what to plant.

Despite the acreage, Lambs Draw’s 270 MW is smaller than the Philadelphia-based Doral’s typical 500 MW project. The size, Cohen said, is limited by what the local power lines — which connect to the Southwest Power Pool grid system — can handle.

“Originally, we wanted it to be more, but ultimately the grid is a constraint,” he said. “It’s healthy at 270, and that’s where we’re going to keep it.”

Nationwide, Doral has 400 MW of solar in operation, another gigawatt under construction, and more than 15 GW in the queue.

The company hasn’t yet selected the panels for Lambs Draw. But its 1.3 GW Mammoth Solar project currently underway in Indiana uses panels from manufacturers in Texas and India. Doral expects to make a similar deal for Lambs Draw, allowing the company to obtain panels quickly enough to access sunsetting federal tax credits and avoid new restrictions on imports from China.

“Solar is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for rural America, and places like northwestern Kansas have an opportunity to have a competitive advantage,” Cohen said. “They have something other people don’t have: flat, tillable farm fields with a strong grid connection.”