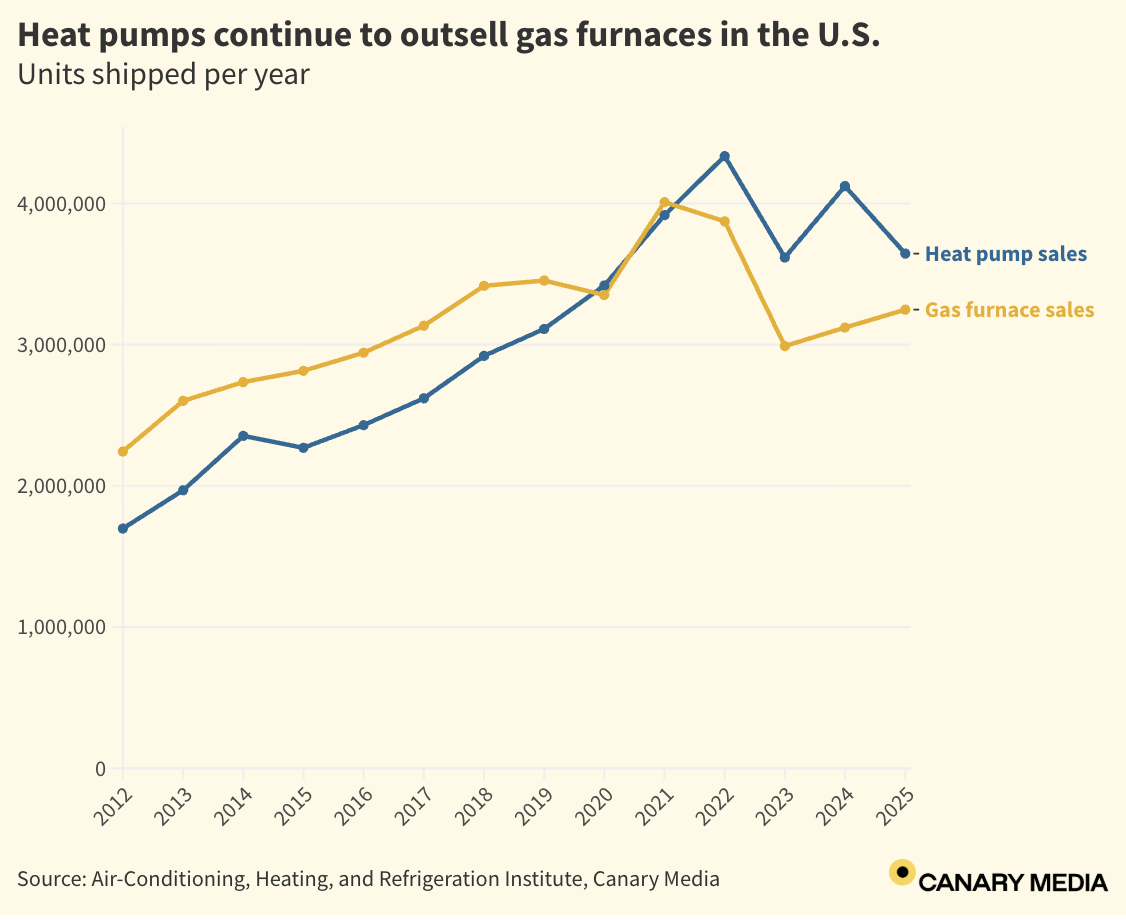

Heat pumps outsold fossil gas–fired furnaces in the U.S. yet again last year.

That’s the fourth year in a row — a testament to Americans’ sustained appetite for the zero-emissions appliances crucial to weaning buildings off planet-warming fossil fuels.

In 2025, 12% more air-source heat pump units shipped in the U.S. than gas furnaces, the next most-popular heating appliance, per data released today from the industry trade group Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute.

Now, that doesn’t necessarily mean that more households are installing the über-efficient appliance instead of furnaces; one home may need multiple heat pump units to replace a single furnace.

And not all the data was good news for the climate. Shipments of gas-powered units ticked upward last year to 3.2 million, while heat pump sales fell to 3.6 million.

But these are year-to-year fluctuations, and the broader trend is still toward heat pumps, experts told Canary Media.

Given the health, comfort, efficiency, and climate benefits of the tech, a complete transition to heat pumps feels inevitable, said Ryan Shea, manager in the carbon-free buildings team at nonprofit RMI. “I think the only question is … how fast the transition happens, not if.”

Electric heat pumps are two-way air conditioners that offer both space cooling and heating. They’re a critical tool to eradicating carbon pollution from buildings, which account for more than one-third of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Because the tech is two to four times as efficient as fossil-fueled systems, heat pumps also save most households money on their energy bills — a winning attribute as more Americans grapple with a cost-of-living crisis.

So why the dip in heat pump shipments last year?

A combination of factors, from tariffs to higher interest rates to a sluggish construction market, was likely to blame, according to experts.

A changeover in refrigerants also played a role. For years, heat pumps and air conditioners utilized the hydrofluorocarbon refrigerant R-410A, which has a strong global-warming potential. But as of Jan. 1, 2025, federal law has required newly manufactured systems to use a less polluting class of refrigerants, called A2Ls.

At least some distributors stocked up on the equipment in 2024, so they’d be ready if customers asked for their broken heat pumps or ACs to be replaced with the same models, said Kevin Carbonnier, senior manager of market intelligence at the nonprofit Building Decarbonization Coalition. That led to a backlog of extra inventory in 2025.

But the refrigerant and market factors “are temporary headwinds,” said Wael Kanj, research manager at electrification advocacy nonprofit Rewiring America. “I don’t think they change the fundamentals. Heat pumps are still the most efficient and comfortable way to heat and cool the home.”

Standing in the way of a total heat-pump takeover has long been their price tag. In 2024, Rewiring America estimated that for a medium-size home, a central heat-pump system costs a median of $25,000. A comparable gas furnace plus central AC system can cost roughly half that.

Even for the same building, contractors may provide hugely varying estimates. Last year, heat-pump research firm Laminar Collective found that for one 2,000-square-foot abode in the Boston area, installers’ quotes for a whole-home heat-pump system could differ by more than $10,000.

The Trump administration has worked against making the tech more affordable. Last year, it terminated home-energy tax credits that reduced the cost of an air-source heat pump by up to $2,000, and of a ground-source, or geothermal, heat pump by an uncapped dollar amount up to 30% of the cost.

Some federal funding to boost heat pumps continues to flow, however, including a $200 million grant to Denver-area local governments. Several states — including California, Georgia, New York, and Indiana — have also been able to tap into an $8.8 billion grant program created under the Biden administration to launch home energy rebate programs that help low- and median-income households afford heat pumps.

Even without the tax credits, thousands of incentive programs that lower the upfront costs of electrification still exist at state, local, and utility levels, Kanj said. Rewiring America and the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center offer online tools so that households can find available credits.

State and local governments are also pursuing creative ways to help heat pumps take off. New England and California have launched multipronged initiatives to raise public awareness and get heating, ventilation, and air conditioning contractors on board. Massachusetts has implemented a lower winter electricity rate for heat pump owners. New York City, which has an all-electric standard for new buildings, launched a $38.4 million program earlier this month to deploy window heat pumps in affordable housing. And California legislators are considering a bill that would cut red tape for homeowners looking to install these electric appliances.

Investors are backing innovation in this space. The Vancouver-based startup Jetson, for example, just raised $50 million to scale its direct-to-consumer approach, which it says cuts installation costs in half.

And although U.S. heat-pump sales didn’t break any annual records in 2025, the tech did quietly achieve a major milestone: In September, more heat pumps shipped than central ACs for the first time.

“It’s really exciting to see the market moving in that direction,” Shea said.

The Building Decarbonization Coalition’s Carbonnier hopes that in the next year or two, “we’ll see it fully cross over” — the way heat pumps overtook gas furnaces four years ago.