This story was first published by Inside Climate News.

The U.S. Department of Energy has approved an $8.6 million grant that will allow the nation’s first utility-led geothermal heating and cooling network to double in size.

Gas and electric utility Eversource Energy completed the first phase of its geothermal network in Framingham, Massachusetts, in 2024. Eversource is a corecipient of the award along with the city of Framingham and HEET, a Boston-based nonprofit that focuses on geothermal energy and is the lead recipient of the funding.

Geothermal networks are widely considered among the most energy-efficient ways to heat and cool buildings. The federal money will allow Eversource to add approximately 140 new customers to the Framingham network and fund research to monitor the system’s performance.

The federal funding was first announced in December 2024 under the Biden administration. However, the contract between HEET and the Department of Energy was not finalized until Sept. 30 and was just announced Wednesday. The agreement, which allows construction to move forward, comes as the Trump administration is clawing back billions of dollars in clean energy funding, including hundreds of millions of dollars in Massachusetts.

“This award is an opportunity and a responsibility to clearly demonstrate and quantify the growth potential of geothermal network technology,” Zeyneb Magavi, HEET’s executive director, wrote in a statement.

The existing system provides heating and cooling to approximately 140 residential and commercial customers in the western suburb of Boston. The network taps low-temperature thermal energy from dozens of boreholes drilled several hundred feet below ground, where temperatures remain steady at 55 degrees Fahrenheit. A network of pipes circulates water through the boreholes to each building, enabling electric heat pumps to provide additional heating or cooling as needed.

“By harnessing the natural heat from the earth, we are taking a significant step toward increasing our energy independence and promoting abundant local energy sources,” Charlie Sisitsky, Framingham’s mayor, wrote.

Progress on the project is a further indicator that despite their opposition to wind and solar, the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress appear to back geothermal energy.

President Donald Trump issued an executive order on his first day in office declaring an energy emergency that expressed support for a limited mix of energy resources, including fossil fuels, nuclear power, biofuels, hydropower, and geothermal energy.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, passed by Republicans and signed by Trump in July, quickly phases out tax credits for wind, solar, and electric vehicles. However, the bill left geothermal heating and cooling tax credits approved under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 largely intact.

A reorganization of the Department of Energy announced last month eliminated the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy but kept the office for geothermal energy as part of the newly created Hydrocarbons and Geothermal Energy Office.

“The fact that geothermal is on this administration’s agenda is pretty impactful,” said Nikki Bruno, vice president for thermal solutions and operational services at Eversource. “It means they believe in it. It’s a bipartisan technology.”

Plans for the expansion project call for roughly doubling Framingham’s geothermal network capacity at approximately half the cost of the initial buildout. Part of the estimated cost savings will come from using existing equipment rather than duplicating it.

“You’ve already got all the pumping and control infrastructure installed, so you don’t need to build a new pump house,” said Eric Bosworth, a geothermal expert who runs the consultancy Thermal Energy Insights. Bosworth oversaw the construction of the initial geothermal network in Framingham while working for Eversource.

The network’s efficiency is anticipated to increase as it grows, requiring fewer boreholes to expand. That improvement is due to the different heating and cooling needs of individual buildings, which increasingly balance each other out as the network expands, Magavi said.

The project still awaits approval from state regulators, with Eversource aiming to start construction by the end of 2026, Bruno said.

“What we’re witnessing is the birth of a new utility,” Magavi said. Geothermal networks “can help us address energy security, affordability and so many other challenges.”

In the race to build America’s first small modular reactors, the U.S. Department of Energy has picked its front-runners.

On Tuesday, the agency awarded a total of $800 million in grants, originally allocated under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, to two projects developing different kinds of 300-megawatt light-water reactors.

These third-generation reactors are shrunken-down, less powerful versions of the time-tested first- and second-generation designs that make up the vast majority of the nation’s fleet of 94 large-scale reactors.

Neither of the third-generation designs — nor any of the fourth-generation models, which use coolants other than water to reach higher temperatures and which the Trump administration has also invested in — has yet been approved by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. And $400 million each for the two just-selected projects is likely to cover only a sliver of their total costs. Getting the green light on a design before a reactor is built doesn’t necessarily always work. The first new large-scale reactors built from scratch in the U.S. in a generation came online as a pair over the past two years but were billions of dollars over budget, in part because construction revealed necessary tweaks to the blueprints that then took developers months to get approved by the NRC. Still, the effort is part of the Trump administration’s push to boost both generations of SMRs in a high-stakes, multibillion-dollar bid to reinforce the nation’s world-leading nuclear industry before China, with its rapid construction of new reactors, becomes the No. 1 fission user.

The federally owned Tennessee Valley Authority will get $400 million to build the first BWRX-300, the reactor designed by a joint venture between the U.S. energy behemoth GE Vernova and the Japanese industrial heavyweight Hitachi. Over the past three years, GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy’s design has emerged as a leader in America’s SMR race, thanks to GE and Hitachi’s long history of successfully building large-scale boiling-water reactors.

In May, Ontario Power Generation, the state-owned utility in Canada’s most populous province, finalized plans to build what’s likely to be the first SMR in North America, one of four BWRX-300 to eventually be built at its Darlington nuclear plant.

Piggybacking off OPG’s effort, the TVA — among the few entities in the U.S. that mirror Canada’s government-owned utility model — plans to construct America’s first BWRX-300 at its Clinch River site, just south of Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Estimates from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggest the reactor will cost significantly more than the far more powerful large-scale Westinghouse AP1000 reactor, which the U.S. finally completed two of at Southern Company’s Alvin W. Vogtle Generation Electric Generating Plant in northern Georgia over the past two years. But the theory with SMRs is that less powerful machines will require a higher quantity of reactors, and that the identical design will bring down costs. The Energy Department grant is meant to discount the price tag of that second-of-a-kind unit.

The other half of the DOE funding has been awarded to Holtec International, which established itself in nuclear power over the last three decades as the industry’s undertaker. The Florida-based manufacturer designed and deployed droves of concrete dry casks meant to keep spent reactor fuel safely stored on-site at nuclear plants until the U.S. government comes up with a solution for radioactive waste. A few years ago, the company entered into the decommissioning business, buying a handful of defunct nuclear plants with the goal of taking them apart. Recently, however, it has looked to become an operator.

Last year, the Energy Department’s Loan Programs Office — recently renamed the Office of Energy Dominance Financing — finalized a $1.5 billion loan to finance the restart of one of Holtec’s plants. The single-reactor Palisades nuclear plant in western Michigan had been the most recent U.S. atomic station to shut down earlier than needed as competition with cheap natural gas and renewables made the facility’s upkeep too costly for its owner, utility giant Entergy. The company sold the plant to Holtec for disassembly in 2022. But as demand for nuclear power has surged in recent years, Holtec proposed reopening the station.

Then, in February, Holtec unveiled fresh plans to expand Palisades with a pair of its SMR-300s. The 300-megawatt reactors are also based on a design used for decades: the pressurized-water reactor, which is even more common than the boiling-water reactor that GE specialized in during the heyday of reactor construction in the mid-20th century.

In a statement, Kris Singh, Holtec’s chief executive officer and chair, called the grant an “essential enabler” of the company’s plans to build the SMR-300, and pointed to Holtec’s exclusive partnership with the South Korean industrial giant Hyundai Engineering and Construction as evidence that the reactor’s design is “marinated with four decades of practical corporate experience.”

“Holtec realizes the future of nuclear energy as a source of reliable baseload electricity to power the economy of the future is realized only if we, in the industry, make the reactors predictably cost competitive,” Singh said. “We consider it our duty to lead the industry in building, owning, and operating the first SMR-300 plant in the United States.”

The Energy Department funding doesn’t guarantee that either project will be completed. NuScale, a fellow third-generation nuclear developer, received $583 million from the Energy Department to fund what was supposed to be the nation’s first SMR plant in Idaho on behalf of Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems, a collection of public utilities in the Beehive State. But the project still went under amid rising costs in November 2023.

The theory that smaller, less powerful reactors will yield lower costs has yet to be proved. So far, only one major SMR has entered into service worldwide, in Russia, where it’s operating on a floating barge in Siberia. The Kremlin-owned Rosatom, the world’s No. 1 exporter of civilian nuclear technology, hasn’t filled its order books for more SMRs and has instead concentrated on large-scale reactors. Likewise, the country building the most nuclear reactors, China, is working toward completing its first third-generation SMR on Hainan. However, the unit is largely seen as destined for export to countries with less demand for large-scale reactors, while China’s two biggest state-owned nuclear utilities have continued focusing on building gigawatt-size units.

The U.S., too, has come around to large-scale reactors. In October, the Trump administration announced a deal to spend $80 billion on 10 new AP1000s, in a move that E&E News suggested made Westinghouse America the new “national champion” in nuclear.

But in a statement, Secretary of Energy Chris Wright suggested there’s room for multiple kinds of reactors.

“President Trump has made clear that America is going to build more energy, not less, and nuclear is central to that mission,” Wright said. “Advanced light-water SMRs will give our nation the reliable, round-the-clock power we need to fuel the President’s manufacturing boom, support data centers and AI growth, and reinforce a stronger, more secure electric grid. These awards ensure we can deploy these reactors as soon as possible.”

Two new battery projects on Virginia’s remote eastern peninsula could signal a growing trend in the clean-energy transition: midsize energy-storage units that are bigger than the home batteries typically paired with rooftop solar, but cheaper and quicker to build than massive utility-scale projects.

The 10-megawatt, four-hour batteries, one each in the tiny towns of Exmore and Tasley, represent this “missing middle,” said Chris Cucci, chief strategy officer for Climate First Bank, which provided $32 million in financing for the two units. Batteries are a critical technology in the shift to renewable energy because they can store wind and solar electrons and discharge them when the sun isn’t shining or breezes die down.

When it comes to energy storage, “we need volume, but we also need speed to market,” Cucci said. “The big projects do move the needle, but they can take a few years to come online.” And in rural Virginia, batteries paired with enormous solar arrays — which can span 100-plus acres — face increasing headwinds, in part over the concern that they’re displacing farmland.

The Exmore and Tasley systems, by contrast, took about a year to permit, broke ground in April, and came online this fall, Cucci said. Sited at two substations 10 miles apart, the batteries occupy about 1 acre each.

Beyond being relatively simple to get up and running, the systems could help ease energy burdens on customers of A&N Electric Cooperative, the nonprofit utility that owns the substations where the batteries are sited, said Harold Patterson, CEO of project developer Patterson Enterprises.

Wait times to link to the larger regional grid, operated by PJM Interconnection, are up to two years. So for now, the batteries will draw power only from the electric co-op, Patterson said. Once they connect to PJM, the batteries will charge when system-wide electricity consumption is down and spot prices are low. Then, the batteries’ owner, Doxa Development, will sell power back when demand is at its peak, creating revenue that will help lower bills for co-op consumers.

“That’s the final step to try to drive down power prices” for residents of Virginia’s Eastern Shore, Patterson said. “Get it online and increase supply in the wholesale marketplace.”

Though the batteries aren’t paired with a specific solar project, they are likely to lap up excess solar electrons on the PJM grid. And since they’ll be discharged during hours of heavy demand, they could help avert the revving up of gas-fired “peaker plants.”

“Peaker plants are smaller power plants that are in closer proximity to the populations they serve, and [they] are traditionally very dirty,” Cucci said. “They’re also economically inefficient to run. Battery storage is cleaner, more efficient, and easier to deploy.”

Gas peaker plants are wasteful partly because of all the energy required to drill and transport the fuel that fires them, said Nate Benforado, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, a nonprofit legal advocacy group.

“Then you get [the fuel] to your power plant, and you have to burn it,” Benforado said. “And guess what? You only capture a relatively small portion of the potential energy in those carbon molecules.”

Single-cycle peaker plants, the most common type, can go from zero to full power in minutes, much like a jet engine. Their efficiency ranges between 33% and 43%.

“Burning fossil fuels is not an efficient way to generate energy,” Benforado said.

“Leaning into batteries is the way we have to go. They’re efficient on the power side but also on the price side.”

Texas proves the financial case for batteries. The state has its own transmission grid, no monopoly utilities, and no state policies to speed the clean-energy transition. Yet it’s gone from zero to some 12 gigawatts of batteries in five years.

In Virginia, A&N Electric Cooperative isn’t the only nonprofit utility investing in energy storage: The municipal utility in the city of Danville, on the North Carolina border, announced earlier this year that it’s building a second battery project of 11 megawatts. Its first system, a 10.5-megawatt battery, which went online in 2022, is on track to save customers $40 million over two decades, according to Cardinal News.

“You look at Texas, where developers are trying to make money on projects,” said Benforado. “And now you see co-ops and municipalities saying, ‘This can save our customers significant amounts of money.’ That, to me, is very telling about the economics of batteries.”

Those economics are even rosier in light of the federal tax credits available for grid batteries, among the few green incentives to survive the budget bill that congressional Republicans passed this summer. Those credits start phasing down in 2033.

While nonprofit utilities in Virginia aren’t impacted by a 2020 state law that requires investor-owned Dominion Energy and Appalachian Power Co. to decarbonize by 2045 and 2050, respectively, they help show what’s possible for the state.

“We need to build things,” Benforado said, especially in the face of skyrocketing demand from data centers. “The question is, are we going to build clean resources or not? We need to build batteries, not gas.”

Climate First Bank and Patterson Enterprises, for their part, have more midsize energy-storage systems in the works. In fact, in December they expect to break ground on another 10-megawatt project — in Wattsville, 20 miles up the road from Tasley.

“We are talking to a lot of developers on projects ranging from 2 megawatts to 10 or 15 megawatts,” Cucci said. “A lot of those players are saying, ‘Let’s shift a little more heavily into storage.’”

WESTERN MACEDONIA, Greece — For more than a decade, Lefteris Ioannidis had been saying what no one wanted to hear: Coal is dying, and it’s time to prepare for what comes next.

He could see the writing on the wall while serving as mayor of Kozani, the largest city in Western Macedonia, even as other local politicians wanted to build new power plants and dig more coal from the region’s sprawling mines. The president of the coal workers’ union said Ioannidis was dead wrong.

But coal production had been sagging since the early 2000s. The power plants were getting too costly to run, thanks to new pollution rules. And extracting and burning the fossil fuel — which in Western Macedonia is mined in vast open pits that over the decades have destroyed homes, entire villages, and lives — was clearly incompatible with the European Union’s vision for a green future.

Still, even Ioannidis didn’t believe Greece would abandon coal so soon.

Just over a decade ago, more than half the country’s electricity was produced by burning through mountains of lignite, the lowest-grade form of coal. Now, if all goes according to plan, Greece aims to shutter its last two coal-fired power plants next year and stop producing coal from most of its mines, including one that is among the largest in Europe. In coal’s place, the country is building clean energy — mostly solar — at a feverish pace.

Western Macedonia, a landlocked and sparsely populated region far north of Athens and the iconic whitewashed buildings of the Cyclades islands, is at the center of this rapid transition.

The region sits atop the biggest lignite deposits in Greece. Over the course of six decades, the once state-owned PPC Group pulled hundreds of millions of metric tons of coal from the area’s soil, producing thousands of jobs and eventually most of Greece’s electricity — along with devastating environmental and health consequences.

Today, things are changing. Blue-black lakes of solar panels shimmer across the valley floor, busily converting the bountiful Greek sun into clean energy, while others wait to be plugged into the grid. The installations stretch to the edges of quiet mines and surround idled power plants. Lonely plumes of steam escape from the cooling towers of the few coal units that remain online, wavering in the wind like white flags of surrender.

Soon, PPC will complete the construction of 2.1 gigawatts of solar in Western Macedonia, erected mostly on top of remediated coal lands. It will be the largest cluster of solar panels in Europe. Most of it was built within the last 12 months.

The success of the region’s energy transition is undeniable. But so too is the failure to build an economy for the post-coal era. Even though Greece announced back in 2019 that it would eliminate coal, uncertainty reigns over Western Macedonia’s future, and the region remains wracked by poverty and unemployment.

“We had an economy dominated just from coal, and everybody knew that the coal would have to end,” said Ioannidis. “But nobody did anything to prevent the disaster. It’s like the Titanic — everybody dancing on board, but the disaster is coming.”

Most of PPC Group's massive solar cluster in Western Macedonia was built recently, as is visible when comparing satellite imagery from October 2024 to April 2025.

The situation underscores an urgent question as 17 other European nations work to eliminate coal over the coming years: How can a country do what’s right for the planet without wronging the people who depend on fossil fuels for jobs?

The European Union is searching for answers: In 2021 it created a €17.5 billion fund “to ensure no one is left behind on the road to a greener economy.”

The following year, Greece became the first country to have a just-transition plan approved by this fund. But to date, only a sliver of the nearly €1 billion allocated specifically to Western Macedonia has trickled into the impacted communities. There’s not yet a large-scale flagship project in operation — something to demonstrate what a world without coal might look like.

Ioannidis says the lack of progress is unacceptable, the result of a top-down, Athens-led approach that has left little room for the locals to shape their own destiny.

“The main path is to create a bottom-up strategy,” he said. “But I’m not optimistic. I’m not waiting for anything from the government. For them, Western Macedonia is only a very small part of Greece. … Anything outside Athens, it’s not a priority.”

This sense of fatalism hangs over the region like smog. Frustrated by the lack of progress, many residents are leaving in search of better prospects.

It’s a devastating feedback loop: Every working-age resident who pursues a job in Athens or Thessaloniki, every young person who goes off to university and never returns, is one less person to help wrest Western Macedonia from the quicksand of its dirty past. The task of inventing the future becomes harder with each departure — and the sense that it is possible to do so becomes that much more remote.

On a warm Sunday evening in September, every bench in Plateia Nikis, Kozani’s main plaza, was full.

Conversation rose from the tavernas that line the west side of the plaza. Groups of teenagers roamed the pedestrian-only street that feeds into the plaza from the south, pushing one another around and giggling their way into one of several nearby arcades. A child kicked a soccer ball in the plaza’s center and suddenly 10 more appeared; a game began. Another cut across the match, running not after the ball but to hug her grandmother, whom she had spotted from across the way. An elderly couple sat next to me on a bench, and the man offered me a cigarette. I declined politely in Greek, and together we watched silently as the fading sun painted the Kozani clock tower gold.

Just blocks away, the atmosphere was far less vibrant. As I walked away from Plateia Nikis, the bustling shops and cafés gave way to empty storefronts, their smudged windows covered in white paper signs with big red letters that read “ΕΝΟΙΚΙΑΖΕΤΑΙ” — “for rent.”

Outside a bar on one of these side streets, I met up with Sokratis Moutidis, the longtime editor-in-chief of Chronos Kozanis, Western Macedonia’s oldest newspaper. He and two other residents who sat with us explained that these quiet streets were once home to nice shops.

The contrast illustrates how Western Macedonia is struggling to adapt to the end of coal, its core industry for over half a century.

Then entirely state-owned and known as the Public Power Corporation, PPC opened its first major lignite power plant in 1959, perched on the edge of a coalfield located about 15 miles north of Kozani. Its smokestack jutted from the valley floor, a symbol of Greece’s rapid modernization; it was the tallest structure in the nation upon completion.

In the decades that followed, PPC built a total of 15 coal-fired units across the region, which provided over 70% of Greece’s electricity at its high-water mark. (The newest one, Ptolemaida 5, was brought online in 2023 — four years after the country decided to eliminate coal — at a cost of nearly €2 billion. PPC will convert it to gas by 2028.) Western Macedonia’s mines swelled in step with its coal fleet, and by the early 2000s Greece was the world’s fourth-largest producer of lignite.

Coal created not just jobs for miners and engineers but also a bustling secondary economy of mechanics, truck drivers, and lunch-spot proprietors. As much as 20% of the working population was employed directly or indirectly by the sector, according to a 2020 World Bank study. Lignite generated a whopping 42% of Western Macedonia’s gross domestic product.

But as soon as world leaders signed the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, awakening at last to the reality of climate change, the clock started ticking, Ioannidis said. It became inevitable that someday time would run out for coal — in Western Macedonia and beyond.

The only question was when.

As mayor of Kozani from 2014 to 2019, Ioannidis was not content to wait around for an answer. In 2016, he organized the city’s first public discussion about life after lignite. He also convinced the World Bank to visit the region in order to create a road map for how it could move beyond coal.

But by the time the World Bank recommendations came out in 2020, the post-lignite era was already hurtling toward Western Macedonia. The year before, just months into his first term, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis had stood before the United Nations Climate Action Summit and pronounced that Greece would “close all lignite power plants, the latest by 2028,” an inspired target for a country in which the industry was so deeply entrenched. That timeline has since been accelerated to 2026.

“We lost many decades to understand the problem, to realize the problem,” said Ioannidis. “Now we don’t have time.”

Though Mitsotakis’ announcement was couched in soaring rhetoric about the imperative to deal with climate change, it was ultimately long-simmering regulatory and economic forces that brought lignite to its knees.

In 2005, the EU launched the Emissions Trading System, a cap-and-trade program that puts a price on carbon dioxide emissions. The scheme hit lignite especially hard because it emits more than other forms of coal do. Five years later, the EU clamped down on air pollution from industrial sources. Meanwhile, the cost of natural gas, wind, and solar power began to plummet. These trends converged, and as the region’s carbon price slowly crept up, the profitability of PPC’s lignite plants went down.

Still, the phaseout came as a surprise.

“In Greek, when we want to say we are in shock, we say ‘Our legs were cut,’” said Ioannis Fasidis, a 44-year-old coal miner and power plant worker who is now president of Spartakos, a major union of PPC workers, via Moutidis, who translated. “It was a shock.”

That shock is still reverberating throughout Western Macedonia.

No region in Greece, itself a shrinking nation, is losing people faster. Between 2011 and 2021, the year of the most recent census, Western Macedonia lost 10.3% of its population. It has one of the highest youth unemployment rates in Europe: In 2023, more than one-third of young people there were out of work, compared with nearly 22% nationwide and 11% across the EU.

The future of Western Macedonia, it feels, is slipping away — even as the region drives the increasingly ambitious Greek energy transition forward.

In April, Mitsotakis and PPC Chairman and CEO Georgios Stassis stood outside the decommissioned Kardia power plant and unveiled a €5.75 billion “green” vision for Western Macedonia.

Some of that plan is already underway — namely PPC’s colossal solar installations and the company’s work restoring already inactive mine lands. But it also included more aspirational proposals, like turning two lignite mines into pumped hydroelectric facilities and converting Ptolemaida 5 to a hydrogen-ready gas-burning facility. In total, PPC says the plan could create up to 20,000 construction jobs and 2,000 permanent jobs.

“If we wanted to be very fast in phasing out coal and developing renewable energy — and mostly solar — we had to leverage all of the weapons in our armory. There, we owned the land, we had space. We owned the grid connections,” explained Elena Giannakopolou, the chief strategy officer of PPC. “That’s why Western Macedonia was such a special place for us. It was our vehicle to the new day.”

I could see that new day dawning when I visited PPC’s expansive Western Macedonia facilities in September.

Immediately outside the silent turbine hall of the former Kardia power plant, whose four units were shut down between 2019 and 2021, electric boilers now sit to help heat Kozani’s buildings during the city’s chilly winters — a job previously done by the lignite plants. Across the street, construction was newly underway on a gas-fired thermal plant that will also help with heating. Five minutes up the road, PPC’s first-ever grid battery facility was being built. The red-and-white cooling tower of Ptolemaida 5 stood in the distance.

A short drive away was the Kardia mine, which once fed piles of lignite to the units of the power plant that shares its name. From within the mine, some PPC engineers explained how the great crater will gradually fill with rain and groundwater and be repurposed as a pumped-hydro station, an old-school form of energy storage that harnesses gravity to squirrel away electricity. Already, a deep blue pond sat on the mine floor as if to suggest the future.

Past the Kardia complex, fields of solar panels stretched so far that when I looked out from among them, I could see only the region’s most striking features in the distance: the occasional coal excavator rising like a skyscraper; the towers of the half-dead, half-alive Agios Dimitrios coal-fired plant; and the mountain peaks that ensconce the Ptolemaida basin, the physical delimiters of a region whose fate was determined by geological machinations long ago.

PPC’s rapid transformation from a lignite giant to a “powertech” firm that develops clean energy and gas is a microcosm of Greece’s energy transition more broadly.

Earlier this year, the country increased its renewable energy targets under its EU-mandated National Energy and Climate Plan. Previously, Greece aimed to get 66% of its electricity from renewables by 2030 — a figure it flirted with this spring. Now it’s targeting 76%, and the virtual elimination of fossil fuels from its grid by 2035. (PPC, meanwhile, says it will see its emissions plummet by a staggering 85% between 2019 and 2028.) Mitsotakis, whose country was once singled out as a laggard on clean energy, is now taking to the Financial Times’ op-ed pages to lecture other nations on “golden rules” for the green transition.

Made with Flourish • Create a chart

For all the progress on renewables, however, fossil fuels are not yet in the country’s past.

Natural gas, that pesky “bridge fuel,” is on the rise in Greece. Once a comparatively small part of the Greek grid, it provided nearly 40% of the country’s power across 2024. The nation has opened major import infrastructure for liquefied natural gas, positioning itself as a hub for Europe, and is proudly courting Chevron and Exxon Mobil to explore for the fossil fuel off the coast of Crete.

Some influential groups are also pushing to keep burning coal.

One prominent example is the coal workers’ union led by Fasidis. We met at a shady café on a hot afternoon in Kozani, and Moutidis, the local journalist, translated. A serious but not unfriendly man, Fasidis brought his two preteen daughters along, who chimed in occasionally when Moutidis was stuck searching for a word.

Fasidis is in active negotiations with PPC about the future of his roughly 1,800 mine and power plant workers. Though he welcomes the company’s new investment plan, he was clear on what the union really wants.

“Our main goal is for lignite, coal, to be alive,” he said. “This is the main demand of the union.”

He clarified that it is “not an economical point of view” but rather one based on energy security concerns. Greece imports all the natural gas it consumes; lignite remains its core domestic fossil fuel. This fact offered Fasidis and his workers a brief reprieve three years ago, after Russia invaded Ukraine and spurred the worst European energy crisis since the 1970s oil shock that pushed Greece to embrace lignite to begin with.

“But it’s not realistic today to talk about lignite,” said Ioannidis, who later pulled up a chair and joined the conversation with Fasidis — a man he had clashed with as the mayor soothsaying the end of coal.

“Lignite is a dead man,” Ioannidis concluded.

That reality was hard to forget even when I stopped by the Agios Dimitrios power plant during my tour of PPC’s energy complex.

In the hulking facility’s coal yard, I was surrounded by screeching conveyor belts carrying lignite, and my eyes watered and nostrils stung from the caustic swirls of coal dust. But I could also see some telling graffiti spray-painted on one of the power plant’s cooling towers. A decade ago, activists had climbed the steel structure and left behind a message: “GO SOLAR” — a message that now, with all the challenges it brings, the region is heeding.

But for all the clean energy being built in Western Macedonia, the boom is creating little wealth for the people who live there.

Konstantinos Siampanopoulos, a 34-year-old resident of Kozani, is a case in point.

Siampanopoulos is a restless entrepreneur. Details of venture after venture dribbled out as we spoke over meze at a Kozani taverna. There’s the fur clothing brand he founded, the accounting firm he runs, and, most recently, a facility where locals can play the squash-like racquet sport padel.

Siampanopoulos is also a longtime investor in renewable energy, one of the few locals who managed to get in early on the region’s solar boom. In 2010, he and his father developed their first solar installations. In partnership with other investors, their portfolio grew to 16 megawatts, including some small hydropower projects. But as the country has become awash in solar, he told me, what was once a prescient and profitable bet has soured.

Holding up a phone displaying the real-time market dashboard from Greece’s grid operator, he showed me the problem for small investors. “Tomorrow, the price is zero. It’s zero for many hours,” he said. “We signed the contract that if the price is zero for more than two hours, we are not paid.”

Put simply: Greece often has more solar power than it can use. Plans to build energy storage will help alleviate this problem, but that’s small comfort for investors like Siampanopoulos right now. Under the current conditions, he and his coinvestors were hardly able to keep up with the loan payments on their installations, let alone earn an attractive profit. They sold 10.8 MW of their portfolio in August.

These price dynamics, among other challenges, have made it difficult for locals to profit from the energy transition.

Overall, at least 95% of the operational or licensed renewable projects in Western Macedonia are owned by large investors, per April 2024 data from Greece’s transmission and distribution grid operators shared by Siampanopoulos; he obtained and analyzed the data in his capacity as a member of the Kozani Chamber of Commerce and president of the local photovoltaic investors’ group. That means only a fraction of the wealth is going directly to residents.

“I characterize this as an air bridge, by which income is transferred from Western Macedonia to somewhere else,” said Lefteris Topaloglou, a professor who runs the Energy Transition and Developmental Transformation Laboratory at the University of Western Macedonia.

In one sense, this is nothing new. Although majority owned by Greece until 2021, PPC was still a single large entity — headquartered elsewhere, in Athens — that controlled the energy infrastructure in Western Macedonia.

But the coal-fired power plants made up for this centralized ownership with jobs. Solar provides neither significant revenue nor employment to residents. PPC declined to disclose the exact number of permanent jobs that its solar installations have created in Western Macedonia to date.

In some ways, this is a good thing. Solar results in so few jobs once installed because it requires no fuel and little maintenance. That’s one reason it is the cheapest form of energy, and that affordability is itself why solar is growing at blazing speed worldwide — giving humanity a chance to kick our self-destructive habit of burning fossil fuels like lignite.

Coal, by contrast, creates jobs because it is extractive. Humans must pilot excavators that disfigure the Earth to produce coal, which then must be transported by humans to power plants, where yet more humans oversee operations. Its economic benefits are a direct function of its pollution, of its destruction; its jobs are paid for with the health of workers and nearby residents and that of the planet.

But the point remains for the people of Western Macedonia: Solar isn’t bringing them jobs.

“This is the employment paradox of the green energy boom,” said Topaloglou.

On a brisk and sunny morning in early October, the marble sidewalks of Athens slick from the previous day’s uncharacteristic downpour, I met Alexandra Mavrogonatou in her office near the Hellenic Parliament.

She offered me an espresso, a comfortable seat, and a history lesson. In June 2022, she explained, Greece became the first country to receive European Commission approval for its €1.63 billion just-transition plan. Most of the money comes from the EU’s broader Just Transition Fund, which supports 96 regions across the bloc.

Mavrogonatou is the head of the directorate of strategic planning and coordination of funds for Greece’s Just Transition Special Authority. That means she oversees the implementation of the country’s just-transition program, from which Western Macedonia was allocated about €994 million. The rest is split between the country’s other main lignite area, Megalopolis, and then among the islands and other mainland regions.

To date, her agency has made some progress: It has approved projects amounting to 50% of the funds and inked contracts with awardees for almost 35% of the funds, she said. But through September, she told me, less than 5% of the money had actually been given to the beneficiaries.

“This percentage may seem low, but we need to take into consideration that we are a newly established program,” Mavrogonatou said. “We’ve had no projects coming from a previous programming period, so we started from scratch — from zero.”

Most of the funding approved by Mavrogonatou’s office so far is for projects in Western Macedonia, she said.

Entrepreneurship has been a main focus, and the office to date has greenlit more than 500 such investments for the region, she said. It funded the creation of a coworking space and a startup incubator in Kozani. The 22-person accounting firm Siampanopoulos manages received approval for funding, and he’s working on securing money for his padel hub, too. The agency has also funded regional support offices in Kozani and the city of Florina — “one-stop shops” for entrepreneurs, she said — as well as a skills development and employment center in Kozani.

But during my five days in Western Macedonia, locals dismissed these sorts of programs as not enough. They are not unwelcome, necessarily, but viewed as insufficient. Ioannidis called them “very, very soft actions.”

“We are full of soft actions and programs,” he told me, weeks before my conversation with Mavrogonatou, while on a break from his job managing a 40-person health clinic in town. As we spoke at his favorite café, the former mayor fielded a steady stream of greetings. Some passersby pulled up a chair, Ioannidis poured them a glass of beer, and they sat and chatted before continuing on their way.

“That’s enough with soft actions, trips, discussions, studies,” he said. “We need jobs. We need something concrete.”

Ioannidis’ frustration is shared by many in the region: Even though it’s been six years since Mitsotakis’ fateful announcement, there’s been no large-scale job creation, and there’s not a clear and broadly understood vision for how to change that.

Above all, the residents I spoke to feel that they’ve had no chance to participate in planning for what comes next.

When I brought up these criticisms to Mavrogonatou in Athens, she said she “totally” disagrees with the notion that locals have had no voice. She pointed to working groups in Western Macedonia, which are staffed by representatives from the local university and municipalities and which are under the supervision of the region’s governor. The idea, she said, is to provide a way for one unified stream of feedback to flow to Athens.

Be that as it may, the perception that the transition is being mismanaged is real — and that perception is eroding trust in the entire process. Ongoing field research from Fenia Pliatsika, a doctoral student in Topaloglou’s lab, found a high level of concern that the transition is suffering because of a lack of trust and “tokenistic participation,” echoing similar peer-reviewed findings published by Topaloglou and Ioannidis in 2022.

Perceived inconsistencies in the government’s stance on clean energy threaten to wash away what little confidence remains.

Again and again, throughout my time in Western Macedonia, residents called out two projects as confusing and unfair.

First, there’s the waste-to-energy facility. Under an EU regulation, Greece needs to rapidly decrease the amount of trash it puts into landfills. Its proposed solution is to construct six incinerators around the country that will burn garbage for energy. That includes a facility PPC intends to build at the site of Ptolemaida 5, to which waste would be trucked in from as far as the island of Corfu. Opposition runs deep. Fasidis singled it out as the only proposed new investment the union is against. As I returned from touring PPC’s energy complex, a protest against the plant was winding down, the shouts of opposition still ringing through Kozani’s narrow streets.

Then, there is the lignite mine in the village of Achlada, near Florina. The facility, which is not owned by PPC, ships its coal across the border to North Macedonia, home to one of the most polluting power plants in Europe. The mine has a contract in place until 2028.

Locals make the point that the government is all but eliminating the industry that has anchored their economy for decades in the name of a green energy transition while embarking on two projects that undermine that very effort. In their view, the government is still allowing dirty activities — but only the ones it finds convenient.

Back in Athens, Mavrogonatou urged patience. She stressed that her agency has had only a few years to achieve something difficult — the wholesale transformation of a regional economy — and that results will take time. The projects approved so far will create 2,500 permanent jobs in Western Macedonia, she said. Her team has until 2030 to spend the money.

“We’re trying to do the best we can for the area,” she said. “We’re not perfect. No one is perfect in this world, but I am pretty sure that very soon, especially during 2026, the area will start seeing the first results of our effort.”

The microchip factory her office approved for funding in 2024 is one example. Greek telecoms firm Intracom plans to break ground soon on a €45 million facility and complete construction by 2027. It will create at least 150 skilled jobs.

She also pointed to her agency’s plan to build an “innovation zone” at the University of Western Macedonia’s main campus. It’s a sweeping idea that includes everything from a green hydrogen hub to a supercomputer, as well as mechanisms for university researchers to commercialize their work via startups. Funding for the project has been approved, but construction has not yet begun.

The projects are all part of the nebulous plan to turn the energy-rich region into something of a tech hub for Greece.

Perhaps the most promising venture on this front is one that Mavrogonatou’s office has nothing to do with: a huge data center proposed by PPC as part of its April investment plan.

The €2.3 billion, 300-megawatt facility would replace the lignite field outside the Agios Dimitrios plant. PPC says it can have the data center online by 2027, a potentially appealing timeline for tech firms that are struggling to swiftly secure energy to power their artificial intelligence strategies.

“Time to market is one of the most critical, if not the most critical, points in this decision,” said Giannakopolou of PPC. “Building the building is not difficult. What’s difficult is to have grid connections, to have electricity to power the data center.”

If the demand is there, PPC says it can scale the facility to 1,000 megawatts — a move that would make it among the largest data centers in Europe and also spur the company to outfit Ptolemaida 5 with a 500 MW combined-cycle gas turbine. The facility would, in theory, help propel the area’s startup ecosystem by attracting young, tech-savvy professionals. PPC declined to disclose exactly how many jobs the data center or its related gas-turbine upgrades would generate.

But these visions of a high-tech economy are tentative at best. PPC has to convince a major tech company to set up a data center in Western Macedonia — and that’s just the first step. PPC said that negotiations are active but declined to provide further detail.

Marquee projects promised to the region have fallen apart before. A €1.4 billion lithium-ion battery manufacturing facility was supposed to bring more than 2,000 permanent jobs; it was abandoned late last year. An €8 billion green-hydrogen complex that pledged an audacious 18,000 direct jobs fizzled out after failing to secure European Commission funding.

Amid these false starts, the pleas for patience from Athens have worn thin. As the journalist Moutidis put it in a message after I spoke with Mavrogonatou, “Since 2019, they’ve been saying, ‘Next year things will be better — just be patient.’”

The hope, of course, is that the cynicism is wrong. That the big ideas do work out — that, very specifically, the data center gets built. The residents I spoke to want the region to see a large-scale project that isn’t coal, not only for the much-needed jobs it will bring but also for the symbolic weight — for the suggestion that it’s possible for Western Macedonia to reinvent itself.

“The first buildings, the beginning of the construction — it will be a good signal,” said Ioannidis. “We need a good signal here. We need a flagship investment. This is the main problem: The people here don’t see a good signal and lose their belief in this process.”

“This is not political,” he clarified, before pausing, searching for the word in English. “It’s psychological.”

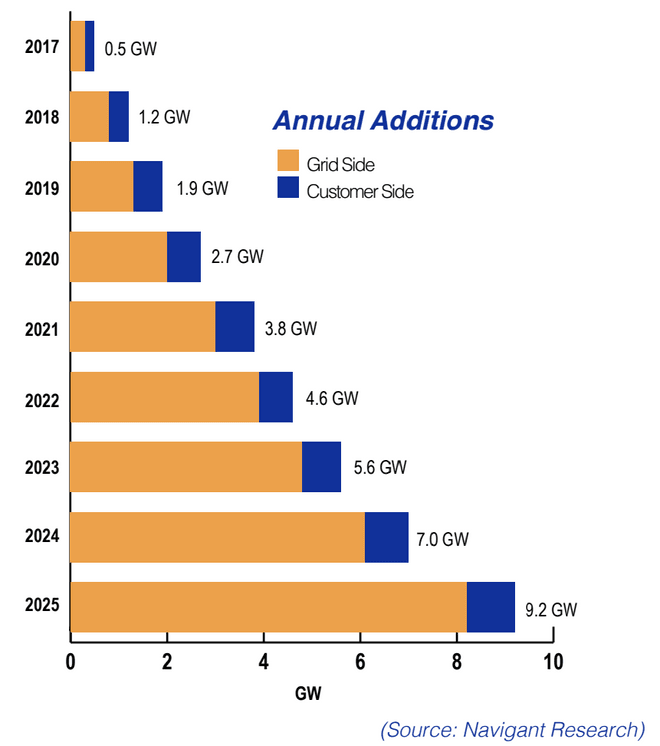

In 2017, the early leaders in energy storage made an audacious bet: 35 gigawatts of the new grid technology would be installed in the United States by 2025.

That goal sounded improbable even to some who believed that storage was on a growth trajectory. A smattering of independent developers and utilities had managed to install just 500 megawatts of batteries nationwide, equivalent to one good-size gas-fired power plant. Building 35 gigawatts would entail 70-fold growth in just eight years.

The number didn’t come out of thin air, though. The Energy Storage Association worked with Navigant Research to model scenarios based on a range of assumptions, recalled Praveen Kathpal, then chair of the ESA board of directors. The association decided to run with the most aggressive of the defensible scenarios in its November 2017 report.

In 2021, ESA agreed to merge with the American Clean Power Association and ceased to exist. But, somehow, its boast proved not self-aggrandizing but prophetic.

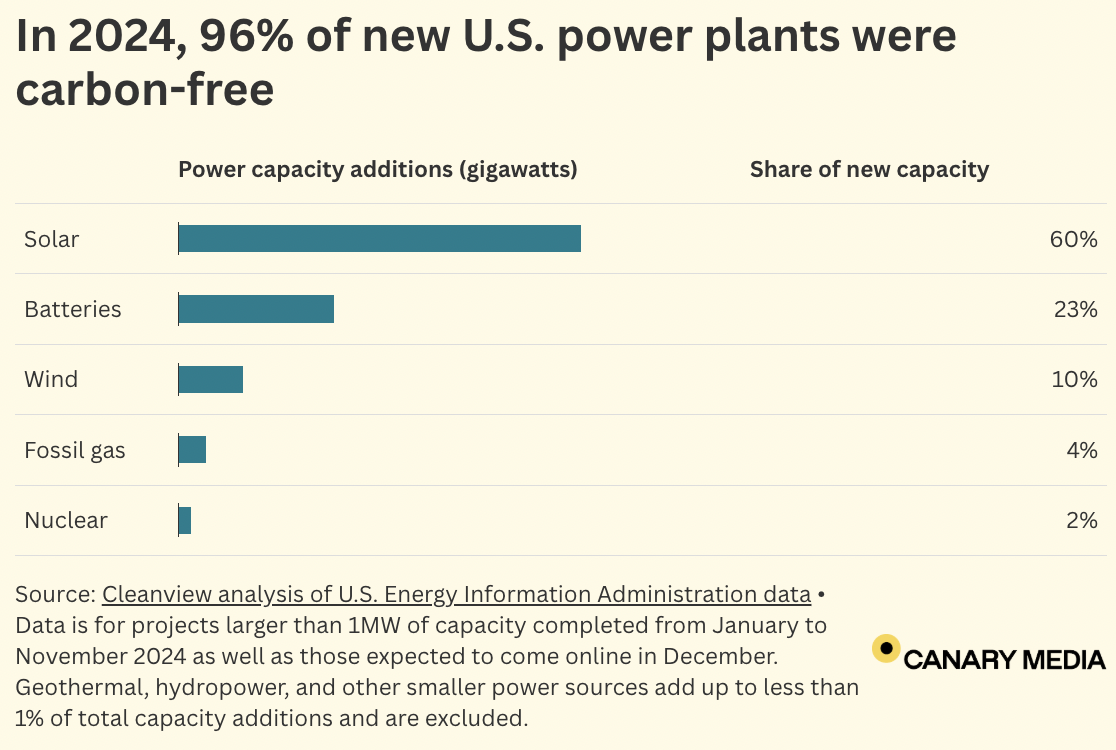

The U.S. crossed the threshold of 35 gigawatts of battery installations this July and then passed 40 gigawatts in the third quarter, according to data from the American Clean Power Association. The group of vendors, developers, and installers who just eight years ago stood at the margins of the power industry is now second only to solar developers in gigawatts built per year. Storage capacity outnumbers gas power in the queues for future grid additions by a factor of 6.5, according to data compiled by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

“Storage has become the dominant form of new power addition,” Kathpal said. “I think it’s fair to say that batteries are how America does capacity.”

Back in 2017, I was covering the young storage industry for an outlet called Greentech Media, a beat that was complicated by how little was happening. There was much to write about the “enormous potential” of energy storage to make the grid more reliable and affordable, but it required caveats like “if states change their grid regulations to allow this new technology to compete fairly on its merits, yada yada yada.”

Those batteries that did get built in 2017 look tiny by today’s standards. The locally owned utility cooperative in Kauai built a trailblazing 13-megawatt/52-megawatt-hour battery, the first such utility-scale system designed to sit alongside a solar power plant. And 2017 saw the tail end of the Aliso Canyon procurement, a foundational trial for the storage industry in which developers built a series of batteries in Southern California in just a handful of months to shore up the grid after a record-busting gas leak — adding up to about 100 megawatts.

“You saw green shoots of a lot of where the industry has gone,” said Kathpal.

California passed a law creating a storage mandate in 2010, then found a pressing need for the technology to neutralize the threat of summertime power shortages. Kauai’s small island grid quickly hit a saturation point with daytime solar, so the utility wanted a battery to shift that clean power into the nighttime. These installations weren’t research projects; they were solving real grid problems. But they were few and far in between.

Kathpal recalled one moment that encapsulated the storage industry’s early lean era. At the time, he was developing storage projects for the independent power producer AES. One night around midnight, he parked a rented Camry off a dirt road and pointed a flashlight through a sheet of rain. It was his last stop on a trip to evaluate potential lease sites for grid storage ahead of a utility procurement — looking at available space, proximity to the grid, and stormwater characteristics. But once the utility saw the bids, it decided not to install any batteries after all.

“The storage market is built not only from Navigant reports but also from moments like that,” he said. “We had to lose a lot of projects before we started winning.”

Now that same utility is putting out a call for storage near its substations — exactly the kind of setting Kathpal had toured in the rain all those years ago.

Indeed, many of the projects connected to the grid this year started with developers anticipating future grid needs and putting money on the line for storage back around the time ESA was formulating its big goal, said Aaron Zubaty, CEO of early storage developer Eolian.

“Eolian began developing projects around major metro areas in the western U.S. starting in 2016 and putting the queue positions in that then became operational in 2025,” Zubaty said. The 200-megawatt Seaside battery site at a substation in Portland, Oregon, is one example.

Though the storage industry pioneers somehow nailed the 35-gigawatt goal, market growth defied their expectations in several important ways.

ESA had expected more of a steady ramp to the 35 gigawatts, said Kelly Speakes-Backman, who served as its chief executive officer from 2017 to 2021. But the storage market ran into plenty of false starts, such as when states passed mandates to install batteries but never enforced them, and when federal regulators ordered wholesale markets to incorporate storage but regional implementation dragged on for years.

The ESA report predicted that 2018 deployments would cross the 1-gigawatt threshold, which didn’t actually happen until 2020. But real installations significantly outpaced the expected numbers in the run-up to 2025. The group hoped to hit 9.2 gigawatts installed this year, and instead the industry is on track to deliver 15 gigawatts.

“Once it hit, it really hit,” Speakes-Backman said.

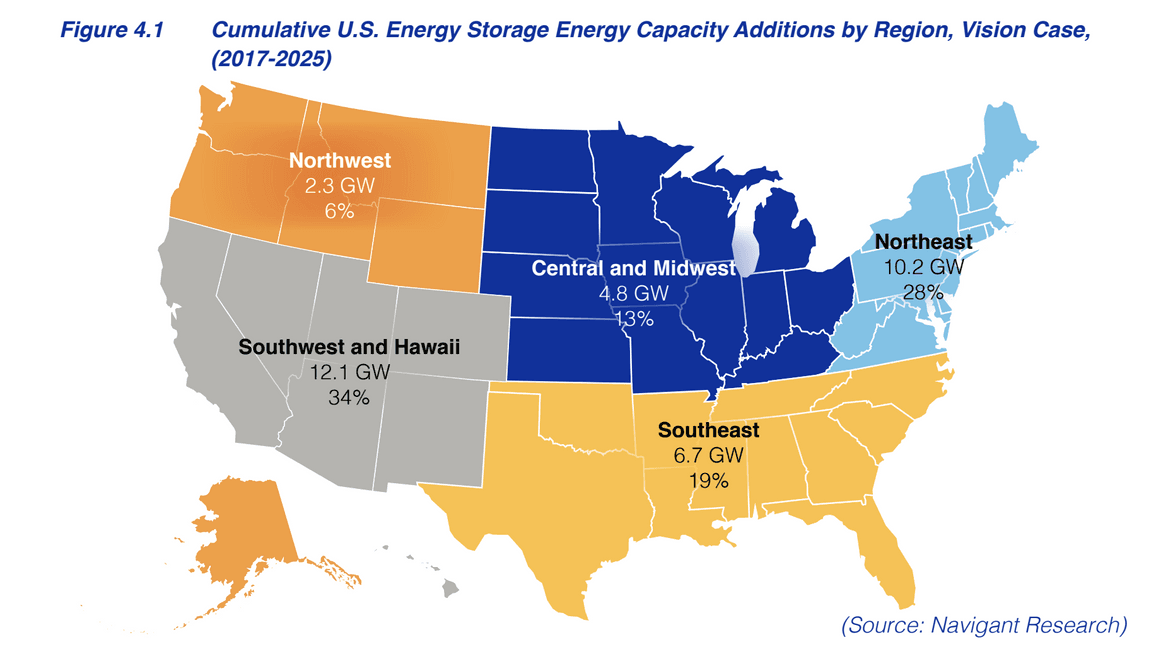

The regional breakdown of storage growth didn’t play out as ESA expected, either. The analysis anticipated that the Northeast would install more than 10 gigawatts, nearly as much as the Southwest (including California and Hawaii); after all, it noted, New England states had passed “aggressive greenhouse gas reduction policies.”

In fact, the Northeast has done exceedingly little to build large-scale storage. (Zubaty told me that “largely dysfunctional power markets combined with utilities that have excessive regulatory capture” thwarted many good battery projects there.)

But other regions surpassed ESA’s expectations. California, Texas, and Arizona alone hold roughly 80% of all U.S. battery storage capacity. This lopsided concentration of storage could be seen as a weakness of the industry. Noah Roberts, executive director of the recently formed Energy Storage Coalition, which advocates for storage in federal arenas, said the pattern reflects how storage has sprung up in spots that suffer acute grid stress.

“Where energy storage has been deployed to date, it is and has been concentrated in areas that have had the greatest reliability need,” he said. “That is Texas and California, where in the early 2020s there were blackouts or brownouts that were quite significant.”

Now, Roberts said, other regions can look at California and Texas for empirical data on how the storage influx has helped reliability while lowering grid costs, for instance by avoiding power scarcity during heat waves and pushing down peak prices. “We’re really seeing the broadening of the geographic footprint of energy storage deployment,” he said, to regions like the Midwest and the mid-Atlantic, which are grappling with unanticipated load growth.

Indeed, the ESA did not foresee the artificial intelligence boom sending power demand through the roof. Instead, its report predicted, “Electrified transportation will likely provide the largest source of new system load.” Now the storage industry has emerged as the biggest player in constructing firm, on-demand power plants, at the exact time that rapid power construction has become the key limiting factor in the AI arms race.

The storage market outdid expectations in one other major way. In 2017 the storage industry was intently focused on getting batteries installed, not so much on where they came from. Since then, bipartisan sentiment has shifted from unfettered global trade to a distinct preference for American manufacturing. The U.S. has made batteries for electric vehicles for years now, but the lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries favored for grid storage have come almost exclusively from China. Now manufacturers are opening domestic cell production for grid storage, just in time for new rules that constrain federal tax credits for battery projects with too much material from China.

LG Energy Solution opened a factory to produce battery cells for grid storage in Michigan this summer that is capable of producing up to 16.5 gigawatt-hours at full capacity; the company expects to raise its North America capacity to 40 gigawatt-hours by the end of 2026. “All of our projects integrated before 2022 combined are smaller than some of our newer individual projects,” noted Tristan Doherty, chief product officer of LG Energy Solution subsidiary Vertech, which focuses on grid batteries.

Tesla is opening domestic LFP battery fabrication in 2026. Fluence announced the first shipment of its “domestically manufactured energy storage system” in September. Newcomers with novel chemistries for longer-duration storage are joining the fray, such as Form Energy and Eos Energy, both of which operate factories outside Pittsburgh.

“By the end of next year, we anticipate reaching the milestone of producing as many domestic energy storage battery cells as we need for demand,” Roberts said. “That is a pretty miraculous story that not many industries have the ability to say they’re able to accomplish.”

The storage industry was vindicated in stretching its aspirations beyond what many thought was possible. Those early adopters knew their technology was valuable, but even they didn’t guess how it would connect with the generational forces reshaping the U.S. economy, from AI to the onshoring of industry.

A clarification was made on Dec. 4, 2025: This story has been updated to reflect that LG Energy Solution’s goal to reach 40 GWh of battery-manufacturing capacity is for North America as a whole, not just for the company’s Michigan plant.

Geothermal energy is undergoing a renaissance, thanks in large part to a crop of buzzy startups that aim to adapt fracking technology to generate power from hot rocks virtually anywhere.

Meanwhile, the conventional wisdom on conventional geothermal — the incumbent technology that has existed for more than a century to tap into the energy of volcanically heated underground reservoirs — is that all the good resources have already been mapped and tapped out.

Zanskar is setting itself apart from the roughly one dozen geothermal startups currently gathering steam by making a contrarian bet on conventional resources. Instead of gambling on new drilling technologies, the Salt Lake City–based company uses modern prospecting methods and artificial intelligence to help identify more conventional resources that can be tapped and turned into power plants using time-tested technology.

On Thursday, Zanskar unveiled its biggest proof point yet.

The company announced the discovery of Big Blind, a naturally occurring geothermal system in western Nevada with the potential to produce more than 100 megawatts of electricity. It’s the first “blind” geothermal system — meaning that the underground reservoir has no visible signs, such as vents or geysers, and no data history from past exploration — identified for commercial use in more than 30 years.

In total, the United States currently has an installed capacity of roughly 4 gigawatts of conventional geothermal, most of which is in California. That makes the U.S. the world’s No. 1 user of geothermal power, even though the energy source accounts for less than half a percentage point of the country’s total electricity output.

The project is set to go into development, with a target of coming online in three to five years. Once complete, it will be the nation’s first new conventional geothermal plant on a previously undeveloped site in nearly a decade, though it may come online later than some next-generation projects.

“We plan to build a power plant there, and that means interconnection, permitting, construction, and drilling out the rest of the well field and the power plant itself. But that’s all pretty standard, almost cookie-cutter,” said Carl Hoiland, Zanskar’s cofounder and chief executive. “We know how to build power plants as an industry. We’ve just not been able to find the resources in the past.”

Prospecting is where Zanskar stands out. While surveying, the company’s geologists found a “geothermal anomaly” indicating the site’s “exceptionally high heat flow,” according to a press release. The team then ran the prospecting data through the company’s AI software to predict viable locations to drill wells in order to test the temperature and permeability of the system.

Zanskar drilled two test wells this summer. Roughly 2,700 feet down, the drills hit a porous layer of the resource with temperatures of approximately 250 degrees Fahrenheit. The company said those “conditions exceed minimum thresholds for utility-scale geothermal power” and “contrast greatly” with other areas in the region, which would require digging as far down as 10,000 feet — potentially viable for the next-generation technologies Zanskar’s rivals are pitching.

The firm’s announcement comes as the U.S. clamors for more electricity, in large part because of shockingly high forecasts of power demand from data centers. Many of the tech companies developing data centers, like Google and Meta, are eager to pay big for “clean, firm” power — electricity that is carbon-free and available 24/7. Geothermal, whether advanced or conventional, is a tantalizing option for meeting those standards, and tech giants already anchor some next-generation projects.

Ultimately, Zanskar thinks it can convince data centers to colocate near where it finds resources.

If it’s able to find additional untapped resources that are suitable for conventional technology, Zanskar could deliver new geothermal power faster and cheaper than the flashier startups on the scene can. Those firms, including Fervo Energy and XGS Energy, are making significant progress in bringing down the cost of their drilling techniques, but they are still using new technologies that remain more expensive than the traditional approach, which has been refined over time.

“The core reason we started the company is we came to believe that the Department of Energy’s estimates of hydrothermal potential were just orders of magnitude too low and were all based on studies that are over 20 years old,” Hoiland said. “We think that there’s 10 times more out there than they thought, and that every one of those sites can be 10 times more productive in terms of the number of megawatts they can generate.”

Among the notable cheerleaders of this same theory? The chief executive of the leading next-generation geothermal company. Responding to a post on X from Zanskar cofounder and chief technology officer Joel Edwards describing how much more conventional geothermal remains untapped, Fervo CEO Tim Latimer wrote, “Joel makes a great point about geothermal that you see all the time in resource development: when technology improves, turns out there’s a lot more of something than we thought.”

Colorado just set a major new climate goal for the companies that supply homes and businesses with fossil gas.

By 2035, investor-owned gas utilities must cut carbon pollution by 41% from 2015 levels, the Colorado Public Utilities Commission decided in a 2–1 vote in mid-November. The target — which builds on goals already set for 2025 and 2030 — is far more consistent with the state’s aim to decarbonize by 2050 than the other proposals considered. Commissioners rejected the tepid 22% to 30% cut that utilities asked for and the 31% target that state agencies recommended.

Climate advocates hailed the decision as a victory for managing a transition away from burning fossil gas in Colorado buildings.

“It’s a really huge deal,” said Jim Dennison, staff attorney at the Sierra Club, one of more than 20 environmental groups that advocated for an ambitious target. “It’s one of the strongest commitments to tangible progress that’s been made anywhere in the country.”

In 2021, Colorado passed a first-in-the-nation law requiring gas utilities to find ways to deliver heat sans the emissions. That could entail swapping gas for alternative fuels, like methane from manure or hydrogen made with renewable power. But last year the utilities commission found that the most cost-effective approaches are weatherizing buildings and outfitting them with all-electric, ultraefficient appliances such as heat pumps. These double-duty devices keep homes toasty in winter and cool in summer.

The clean-heat law pushes utilities to cut emissions by 4% from 2015 levels by 2025 and then 22% by 2030.

But Colorado leaves exact targets for future years up to the Public Utilities Commission. Last month’s decision on the 2035 standard marks the first time that regulators have taken up that task.

The commission’s move sets a precedent for other states working to ditch fossil fuels from buildings even as the federal government eliminates home-electrification incentives after Dec. 31. Following Colorado’s lead, Massachusetts and Maryland are developing their own clean-heat standards.

Gas is still a fixture in the Centennial State. About seven out of 10 Colorado households burn the fossil fuel as their primary source for heating, which accounts for about 31% of the state’s gas use.

If gas utilities hit the new 2035 mandate, they’ll avoid an estimated 45.5 million metric tons of greenhouse gases over the next decade, according to an analysis by the Colorado Energy Office and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. They’d also prevent the release of hundreds more tons of nitrogen oxides and ultrafine particulates that cause respiratory and cardiovascular problems, from asthma to heart attacks. State officials predicted this would mean 58 averted premature deaths between now and 2035, nearly $1 billion in economic benefits, and $5.1 billion in avoided costs of climate change.

“I think in the next five to 10 years, people will be thinking about burning fossil fuels in their home the way they now think about lead paint,” said former state Rep. Tracey Bernett, a Democrat who was the prime sponsor of the clean-heat law.

Back in August, during proceedings to decide the 2035 target, gas utilities encouraged regulators to aim low. Citing concerns about market uptake of heat pumps and potential costs to customers, they asked for a goal as modest as 22% by 2035 — a target that wouldn’t require any progress at all in the five years after 2030.

Climate advocates argued that such a weak goal would cause the state to fall short on its climate commitments. Nonprofits the Sierra Club, the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project, and the Western Resource Advocates submitted a technical analysis that determined the emissions reductions the gas utilities would need to hit to align with the state’s 2050 net-zero goal: 55% by 2035, 74% by 2040, 93% by 2045, and, finally, 100% by 2050.

History suggests these reductions are feasible, advocates asserted.

“We’re recommending targets that put us on a technology-adoption curve — a trajectory that’s been seen over and over again,” said Ramón DC Alatorre, senior program manager at the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project. “There’s a tremendous amount [of] mature technology available today in order to be able to meet these targets.”

Heat pumps, for example, have a track record of holding their own even in Denver’s deepest freezes. Some companies are devising ways to bring installation costs way down. And the state is making the tech more affordable via a federally funded rebate program for low-income households and tax credits worth hundreds of dollars for both customers and contractors.

Expecting the market to move more slowly than advocates predicted, the Colorado Energy Office and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment recommended a 41% cut. But then in September, after reviewing stakeholders’ comments, the agencies dropped it to 31% — a “more realistic, yet still ambitious goal,” they wrote.

The agencies’ 41% proposal was “far better supported” by their own analysis, Commissioner Megan Gilman said at the Nov. 12 commission meeting: Agencies found that this target comports with the clean-heat law. The 31% figure, by contrast, seemed untethered to the legislation’s mandates, she noted.

The commission’s decision doesn’t factor in concerns about the cost of decarbonization — nor is it meant to, Gilman said. The regulators will address cost-effectiveness when they evaluate utilities’ specific plans for complying with the statute, which are required every four years. Xcel Energy, the state’s largest utility, will file its next plan in 2027.

Even as Colorado doubles down to leave gas in the past, Xcel isn’t planning to relinquish the fossil fuel anytime soon.

Xcel provides gas to 1.5 million customers across the state. From 2025 to 2029, the utility is seeking to invest more than $500 million per year on the gas system — costs passed on to customers via their energy bills. That’s a bigger investment than Xcel’s $440 million plan for 2024 to 2028 to reduce reliance on gas by implementing clean-heat measures.

Overbuilding gas infrastructure now could have decades-long ramifications for energy bills. “If utilities are not scaling these [electrification] programs, the customers left on the gas systems are ultimately going to face higher costs,” said Courtney Fieldman, utility program director of the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project.

Colorado is nudging gas utilities to instead become clean-heat utilities; for example, lawmakers have directed the companies to pilot zero-emissions geothermal heating projects and thermal energy networks.

Meanwhile, the commission’s November decision sends a clear signal that utilities need to adjust their gas-demand forecast, the Sierra Club’s Dennison said. While advocates hoped that regulators would create more policy certainty by setting targets beyond 2035, commissioners demurred. They have until 2032 to get those standards finalized.

“The targets that conservation advocates have proposed are achievable,” said Ed Carley, an expert on building decarbonization policy at Western Resource Advocates. Adopting them “is really our opportunity to be a leader in achieving our greenhouse gas emissions goals — and demonstrating that market transformation is possible.”

Extreme weather is making the grid more prone to outages — and now FirstEnergy’s three Ohio utilities want more leeway on their reliability requirements.

Put simply, FirstEnergy is asking the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio to let Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co., Ohio Edison, and Toledo Edison take longer to restore power when the lights go out. The latter two utilities would also be allowed slightly more frequent outages per customer each year.

Comments regarding the request are due to the utilities commission on Dec. 8, less than three weeks after regulators approved higher electricity rates for hundreds of thousands of northeast Ohio utility customers. An administrative trial, known as an evidentiary hearing, is currently set to start Jan. 21.

Consumer and environmental advocates say it’s unfair to make customers shoulder the burden of lower-quality service, as they have already been paying for substantial grid-hardening upgrades.

“Relaxing reliability standards can jeopardize the health and safety of Ohio consumers,” said Maureen Willis, head of the Office of the Ohio Consumers’ Counsel, which is the state’s legal representative for utility customers. “It also shifts the costs of more frequent and longer outages onto Ohioans who already paid millions of dollars to utilities to enhance and develop their distribution systems.”

The United States has seen a rise in blackouts linked to severe weather, a 2024 analysis by Climate Central found, with about twice as many such events happening from 2014 through 2023 compared to the 10 years from 2000 through 2009.

The duration of the longest blackouts has also grown. As of mid-2025, the average length of 12.8 hours represents a jump of almost 60% from 2022, J.D. Power reported in October.

Ohio regulators have approved less stringent reliability standards before, notably for AES Ohio and Duke Energy Ohio, where obligations from those or other orders required investments and other actions to improve reliability.

Some utilities elsewhere in the country have also sought leeway on reliability expectations. In April, for example, two New York utilities asked to exclude some outages related to tree disease and other factors from their performance metrics, which would in effect relax their standards.

Other utilities haven’t necessarily pursued lower targets, but have nonetheless noted vulnerabilities to climate change or experienced more major events that don’t count toward requirements.

FirstEnergy’s case is particularly notable because the company has slow-rolled clean energy and energy efficiency, two tools that advocates say can cost-effectively bolster grid reliability and guard against weather-related outages.

There is also a certain irony to the request: FirstEnergy’s embrace of fossil fuels at the expense of clean energy and efficiency measures has let its subsidiaries’ operations and others continue to emit high levels of planet-warming carbon dioxide. Now, the company appears to nod toward climate-change-driven weather variability as justification for relaxed reliability standards.

FirstEnergy filed its application to the Public Utilities Commission last December, while its recently decided rate case and other cases linked to its House Bill 6 corruption scandal were pending. FirstEnergy argues that specific reliability standards for each of its utilities should start with an average of the preceding five years’ performance. From there, FirstEnergy says the state should tack on extra allowances for longer or more frequent outages to “account for annual variability in factors outside the Companies’ control, in particular, weather impacts that can vary significantly on a year-to-year basis.”

“Honestly, I don’t know of a viable hypothesis for this increasing variability outside of climate change,” said Victoria Petryshyn, an associate professor of environmental studies at the University of Southern California, who grew up in Ohio.

In summer, systems are burdened by constant air-conditioning use during periods of extreme heat and humidity. In winter, frigid air masses resulting from disruptions to the jet stream can boost demand for heat and “cause extra strain on the grid if natural-gas lines freeze,” Petryshyn said.

“All the weather becomes supercharged,” Petryshyn said. “We can all expect stronger storms, stronger winds, and more frequent extreme weather that threatens grid stability.”

FirstEnergy has a long history of obstructing measures that would both reduce greenhouse gas emissions and alleviate stress on the power grid.

In February 2024, the company abandoned its interim 2030 goals for cutting greenhouse gas emissions and said it would continue running two West Virginia coal plants. Before that, FirstEnergy backed plans to weaken Ohio’s energy-efficiency goals. And during the first Trump administration, the company urged the Department of Energy to use emergency powers to keep unprofitable coal and nuclear plants running.

FirstEnergy also spent roughly $60 million on efforts to get lawmakers to pass and protect House Bill 6, the law at the heart of Ohio’s largest utility corruption scandal. HB 6’s nuclear and coal bailouts have since been repealed, but the state’s clean-energy standards remain gutted.

Meanwhile, regulators have let FirstEnergy’s utilities charge customers millions of dollars for grid modernization, “which are supposed to support the utility’s ability to adapt and improve the electric grid to rigging challenges from climate change,” said Karin Nordstrom, a clean-energy attorney with the Ohio Environmental Council.

“However, FirstEnergy has not provided the same investment in energy-efficiency programs, which can help manage rising demand at lower cost than expensive capital investment,” Nordstrom said. FirstEnergy should fully exhaust those tools and customer-funded grid-modernization investments before regulators relax the company’s requirements, she added.

Limited transparency makes FirstEnergy’s plan even more problematic, according to Shay Banton, a regulatory program engineer and energy justice policy advocate for the Interstate Renewable Energy Council. Earlier this year, Banton reported on grid disparities in FirstEnergy’s service territories that leave some areas more prone to outages.

“It feels too early for them to request leniency without proposing or implementing more comprehensive mitigations based on a detailed understanding of the root cause,” Banton said.

It’s also likely that FirstEnergy’s rate increase of nearly $76 million for Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co.’s roughly 745,000 customers, approved on Nov. 19, already accounts for some weather-related factors. This summer, spokesperson Hannah Catlett told Canary Media that “the Illuminating Co. service territory generally sees bigger storm impacts” than areas served by FirstEnergy’s other Ohio utilities.

“Our request to adjust the reliability standards is not a step back in our commitment,” Catlett told Canary Media this fall. “We are confident in the progress underway and remain focused on improving reliability through continued investment in the communities we are privileged to serve.”

But fundamentally, additional leeway for weather variation is unnecessary, said Ashley Brown, a former Ohio utility commissioner and former executive director of the Harvard Electricity Policy Group. Averaging utility performance over several years — the way most regulators do as part of setting reliability standards — should already account for that.

“In fact, the standard should always be going up,” Brown added. “You should expect more productivity from the company.”

Jean Gay-Robinson said she “cried tears of joy” when utility ComEd switched all the polluting gas-fired equipment in her Chicago home to modern electric versions, at no cost to her. As a retiree on a fixed income, she is relieved that she’ll likely never have to buy another appliance, her energy bills are lower, and her home feels safer. “I don’t have to worry about gas blowing up or carbon monoxide, that kind of nonsense,” she said.