At the start of next year, companies that make and buy energy-intensive commodities like steel and aluminum will enter the era of CBAM — the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

CBAM is a first-in-the-world policy by the European Union that charges fees on imports based on how much planet-warming pollution was produced in their manufacturing. On Jan. 1, 2026, the carbon tariff will officially take effect, raising costs for European businesses that source products from dirty facilities abroad.

The policy is part of the EU’s broader effort to drive the decarbonization of heavy industries in the 27-member bloc as well as globally. It’s already having a ripple effect, with other countries considering adopting their own carbon-pricing schemes and international firms investing in cleaner technologies to make their exports more enticing to Europe.

Here’s what to know as the landmark policy goes into effect.

In 2005, the EU launched the Emissions Trading System, the first scheme in the world to limit greenhouse gas emissions from power plants and industrial facilities. The ETS caps the total amount of carbon pollution that each operator is allowed to spew. The companies can then buy allowances that give them the right to generate 1 metric ton of CO2-equivalent. The idea is that making it costlier to pollute will incentivize businesses to clean up their operations.

Until now, however, the ETS has given what experts call a “free pass” to producers of certain trade-exposed commodities. Manufacturers argued that raising the costs of producing goods in Europe would make their industries less competitive on the global market. It could also push key customers, including European automakers, to import cheaper materials from countries without stringent climate policies — a phenomenon known as “carbon leakage.”

As the EU phases out these free passes, CBAM is designed to plug such a leak.

“It doesn’t make sense that you basically ask your own producers to produce in a certain way, to be as clean as possible, or else ask them to pay a price, and then let others — competitors from outside Europe — bring in their products and then compete unfairly,” Mohammed Chahim, the European Parliament’s lead negotiator on the carbon border fee, said on the Energy Policy Now podcast earlier this year.

The EU officially finalized CBAM’s rules in May 2023. Later that year, a “transitional phase” began for importers of goods from six carbon-intensive sectors: aluminum, cement, electricity, fertilizers, hydrogen, and iron and steel. Companies had to begin filing quarterly reports listing the direct and indirect carbon emissions of those products.

On Dec. 31, that phase will end, kicking off the “definitive period.”

Starting next month, in addition to tracking emissions, importers will pay a fee on covered products like steel rods, metal wiring, and ammonia. Initially, the fee will be a small percentage of the average quarterly price of CO2 allowances under the ETS — though participants could pay less, or nothing at all, if the exporting country has a similar carbon-pricing scheme in place. Over eight years, the CBAM tariff will gradually increase to represent 100% of the weekly average allowance price.

At the same time, the EU will wind down the special treatment it’s given to trade-exposed industries under the regional cap-and-trade scheme, requiring European manufacturers to gradually pay more for their facilities’ emissions.

The free allowances were “always viewed as a bit of a black mark on Europe’s decarbonization ambitions,” said Trevor Sutton, who leads the program on trade and the clean energy transition at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. European regulators have billed CBAM as a “necessary component” to meeting the region’s climate goals — a way to curb industrial emissions without endangering its economy, he added.

To start, the rules will only apply to importers that bring in more than 50 metric tons of goods every year. According to the EU, this threshold excludes roughly 90% of importers, who are mainly small and medium-sized businesses, but still captures around 99% of emissions from CBAM-covered goods, since large manufacturers represent the bulk of industrial imports.

CBAM has dominated global discussions on climate policy and trade in recent years. But the regulation itself is surprisingly narrow in scope. Targeted products only make up 3% of EU imports from countries outside the bloc. And the carbon footprint of those goods collectively represents about 0.31% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2022, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Still, “it’s a topic that inspires intense emotions,” Sutton said.

Critics, including Europe’s trade partners in the Global South, have argued that the carbon tariff amounts to protectionism — an excuse to shut out foreign competition — and “green imperialism,” since Europe is unilaterally making decisions that affect producers abroad. Mozambique, for instance, sends 97% of its aluminum exports to the EU, leaving it especially exposed.

Manufacturers within the EU have also pushed back against CBAM and the related decline in free CO2 allowances, claiming that the measures put companies at a competitive disadvantage in global markets and will inflate costs for producers. Last week, the head of French aluminum producer Constellium urged Europe’s regulators to “eradicate” CBAM altogether. Importers and their suppliers have also expressed frustration at the onerous and confusing requirements involved with tracing and reporting emissions, Sutton said.

Even so, some of the EU’s key trading partners are responding to CBAM’s signals. Since the measure passed, countries like Brazil and Turkey have introduced domestic carbon-pricing policies. The United Kingdom is set to implement its own Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism starting in 2027. China, for its part, has started shipping steel made using hydrogen to Italy — a move experts say could set the stage for increasing Chinese green-steel exports.

Sutton said that CBAM “has helped drive a conversation and elevated the salience of carbon pricing” in other countries, while also setting “a foundation for decarbonization of European industry.”

Since spring of last year, North Carolina’s largest utility has been testing whether household batteries can help the electric grid in times of need — and now the company wants to roll out the plan to businesses, local governments, and nonprofits, too.

Duke Energy has already paid hundreds of North Carolinians to let it tap power from their home storage systems when electricity demand is highest. It’s Duke’s first foray into running a “virtual power plant,” in which the company manages electricity produced and stored by consumers, much as it would control generation from its own facilities.

In September, the utility proposed a similar model for its nonresidential customers, asserting that the scheme will save money by shrinking the need for new power plants and expensive upgrades to the grid. The recognition signals a way forward for distributed renewable energy and storage as state and national politicians back away from the clean energy transition.

The initiative now needs approval from the five-member North Carolina Utilities Commission, where the virtual-power-plant model has faced some skepticism. But the apparent merits of Duke’s plan, which has broad backing, may be too enticing for commissioners to ignore — especially when the state is grappling with rising rates and voracious demand from data centers and other heavy electricity users.

“In an era of massive load growth, something that should lower costs to customers while helping meet peak demand — to me, it’s an absolute no-brainer,” said Ethan Blumenthal, regulatory counsel for the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, an advocacy group. “I’m hopeful that [regulators] see it the same way.”

Duke’s trial residential battery incentives grew out of a compromise with rooftop solar installers. Like many investor-owned utilities around the country, the company sought to lower bill credits for the electrons that solar owners add to the grid. When the solar industry and clean energy advocates fought back, the scheme dubbed PowerPair was born.

The test program provides rebates of up to $9,000 for a battery paired with rooftop photovoltaic panels. It’s capped at roughly 6,000 participants, or however many it takes to reach a limit of 60 megawatts of solar. Half of the households agree to let Duke access their batteries 30 to 36 times each year, earning an extra $37 per month on average; the other half enroll in electric rates that discourage use when demand peaks.

The incentives have been crucial for rooftop solar installers, who’ve faced a torrent of policy and macroeconomic headwinds this year, and they’ve proved vital for customers who couldn’t otherwise afford the up-front costs of installing cheap, clean energy.

But the PowerPair enrollees already make up 30 megawatts in one of Duke’s two North Carolina utility territories and could hit their limit in the central part of the state early next year, leaving both consumers and the rooftop solar industry anxious about what’s next.

Duke’s latest proposal for nonresidential customers — which, unlike the PowerPair test, would be permanent — is one answer.

The proposed program is similar to PowerPair in that it’s born of compromise: Last summer, the state-sanctioned customer advocate, clean energy companies, and others agreed to drop their objections to Duke’s carbon-reduction plan under several conditions, including that the utility develop incentives for battery storage for commercial and industrial customers. The Utilities Commission later blessed the deal.

“This was pursuant to the settlement in last year’s carbon plan,” said Blumenthal, “so it’s been a long time coming.”

While many industry and nonprofit insiders refer to the scheme as “Commercial PowerPair,” its official title is the Non-Residential Storage Demand Response Program.

That name reflects the incentives’ focus on storage, with solar as only a minor factor: Duke wants to offer businesses, local governments, and nonprofits $120 per kilowatt of battery capacity installed on its own and just $30 more if it’s paired with photovoltaics.

The maximum up-front inducement of $150 per storage kilowatt is much less than the $360 per kilowatt offered under PowerPair. But more significant for nonresidential customers could be monthly bill credits: about $250 for a 100-kilowatt battery that could be tapped 36 times a year, plus extra if the battery is actually discharged.

Unlike households participating in PowerPair, which must install solar and storage at the same time to get rebates, nonresidential customers can also get the incentives for adding a battery to pair with existing solar arrays.

“That could be very important for municipalities around North Carolina that have already installed a very significant amount of solar, but very little of that is paired with battery storage,” said Blumenthal.

Duke has high hopes for the program, projecting some 500 customers to enroll. Five years in, the resulting 26 megawatts of battery storage would help it avoid building nearly 28 megawatts of new power plants to meet peak demand, saving over $13.6 million. That’s significantly more than the cost of providing and administering the incentives, which Duke places at nearly $11.8 million.

“The Program provides a source of cost-effective capacity that the Company’s system operators can use at their discretion in situations to deliver economic benefits for all customers,” Duke said in its September filing to regulators. “Importantly, the Company received positive feedback from its customers … when sharing the details of the Program.”

Indeed, the proposal has been met with support not just from the Sustainable Energy Association and other clean energy groups but also organizations like the North Carolina Justice Center, which advocates for low-income households. It earned praise from local governments represented by the Southeast Sustainability Directors Network and conditional support from the state-sanctioned customer advocate, known as Public Staff, too.

The good vibes continued last week, when Duke responded positively to detailed suggestions from these parties on how to improve the program. That included a request from Public Staff that the company raise the per-customer limit on battery capacity to align with the maximum amount of solar that a business or other nonresidential consumer can connect to the grid, which is currently 5 megawatts.

“Larger batteries sited at larger customer sites can help provide more significant system benefits and can reduce the need for incremental utility-owned energy storage installed at all ratepayers’ expense,” the agency told regulators in its November comments. It recommends a cap tied to a customer’s peak demand; for example, a business that consumes more energy at once should get incentives for a bigger battery. Duke agreed in its Dec. 5 comments, calling that limit “reasonable.”

Still, questions remain about how to make the incentives most impactful.

Public Staff, for instance, believes Duke should increase its monthly payment to customers for keeping their batteries charged and ready to deploy. This “capacity credit” is now set at $3.50 per kilowatt but effectively reduced to $2.48, because the utility assumes that a percentage of users won’t properly maintain their systems, based on its experience with households. The company calls that a “capability factor,” but the agency dubs it “collective punishment” for all customers and says it should be eliminated or recalibrated for “more sophisticated” nonresidential participants.

Raleigh, North Carolina–based 8MSolar, a member of the Sustainable Energy Association, is among the many installers that have been eagerly anticipating Duke’s proposal.

The program on its own likely won’t “move the needle unless the incentives get bumped up,” said Bryce Bruncati, the company’s director of sales. However, the scheme could tip the scales for large customers when stacked on top of two federal tax opportunities: a 30% incentive available through the end of 2027 and a deduction tied to the depreciation value of the system — up to 100% thanks to the Republican budget law passed this summer.

“The combined three could really have a big impact for small- to medium-sized commercial projects,” Bruncati said. The Duke program would represent “a little bit of icing on the cake.”

Whatever their size and design, the fate of the incentives rests entirely with the Utilities Commission, now that the final round of comments from Duke and other stakeholders is in. There’s no timeline for a decision.

At least one commissioner, Tommy Tucker, has voiced skepticism about leveraging customer-owned equipment to serve the grid at large. “I’m not a big fan of the [demand-side management] or virtual power plants because you’re dependent upon somebody else,” the former Republican state senator said at a recent hearing, albeit one not connected to the Duke program.

Still, Blumenthal waxes optimistic. After all, Tucker and three other current members of the commission are among those who ruled last year that Duke should present the new incentive program.

“They seem to recognize there is value to distributed batteries being added to the grid,” Blumenthal said. “The fact that [the proposal] is cost-effective is key because the idea is, the more of it you do, the more savings there are.”

Two corrections were made on Dec. 10, 2025: This story originally misstated the number of times a year that Duke can tap a PowerPair participant’s battery; it is 30 to 36 times a year, not 18. The story also originally misstated the enrollment Duke expects for the nonresidential program; the utility expects 26 megawatts of batteries, not 26,000 customer participants.

ITHACA, N.Y. — A faded-red wellhead emerged in the middle of a pockmarked parking lot, its metal bolts and pipes illuminated only by the headlights of Wayne Bezner Kerr’s electric car. He stepped out of the vehicle into the dark, frigid evening to open the fence enclosing the equipment, which is just down the road from Cornell University’s snow-speckled campus in upstate New York.

We were there, shivering outside in mid-November, to talk about heat.

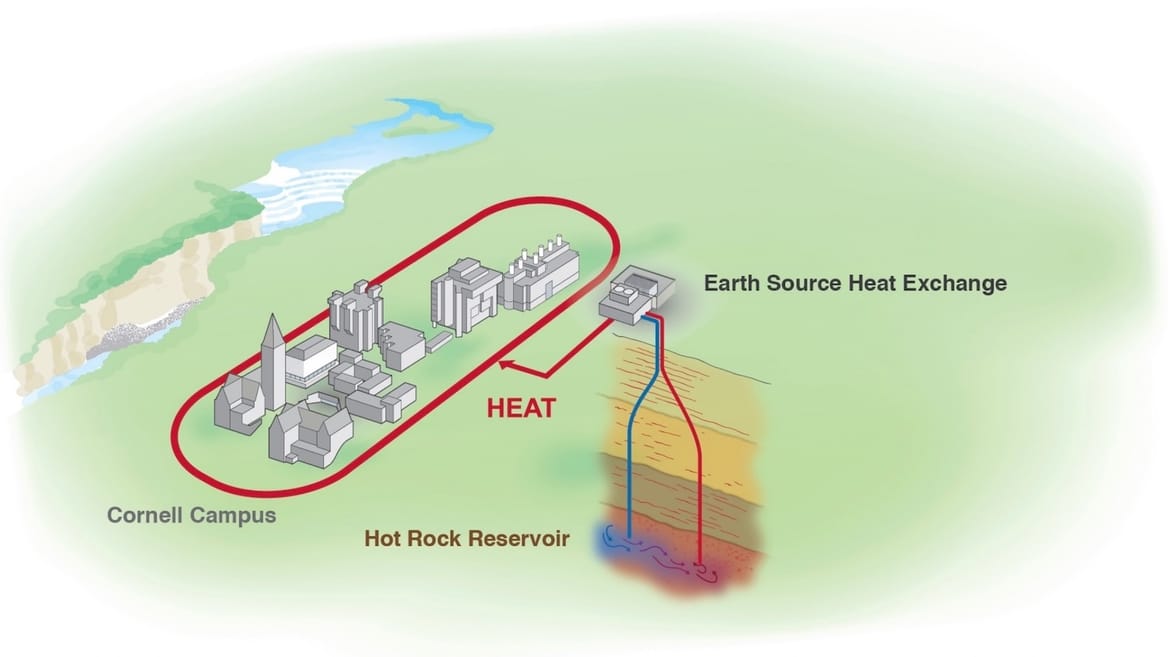

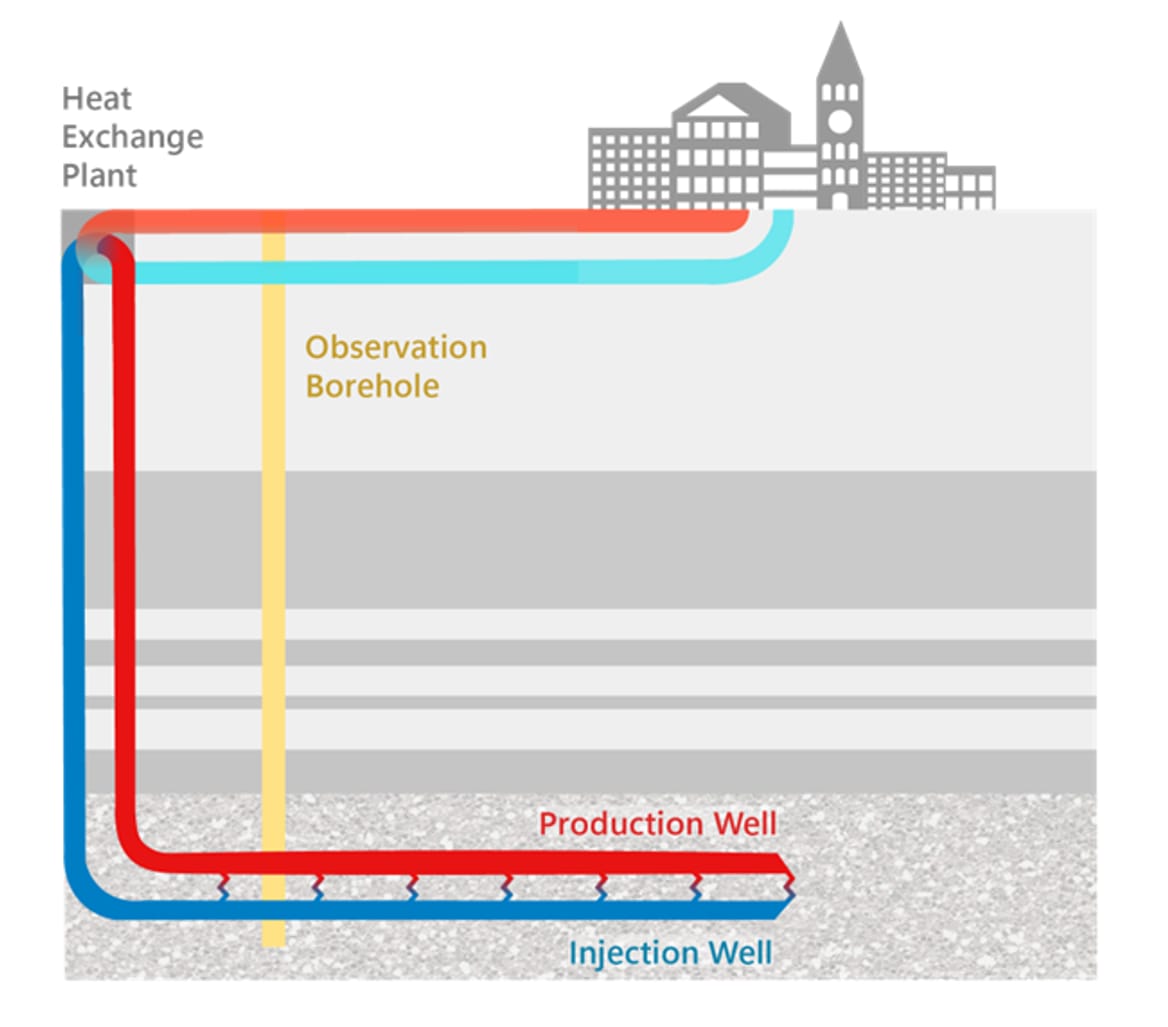

Bezner Kerr is the program manager of Cornell’s Earth Source Heat, an ambitious project to directly warm the sprawling campus with geothermal energy pulled from deep underground. The wellhead was the tip of the iceberg — the visible part of a nearly 10,000-foot-long borehole that slices vertically through layers of rock to reach sufficiently toasty temperatures. Cornell is using data from the site to develop a system that will replace the school’s fossil-gas-based heating network, potentially by 2035.

“We can’t decarbonize without solving the heat problem,” Bezner Kerr repeated like a refrain during my visit to Ithaca.

The Ivy League university is trying to accomplish something that’s never been done in an area with rocky geology like upstate New York’s. Most existing geothermal projects are built near the boundaries of major tectonic plates, where the Earth’s warmth wells up toward the surface. Iceland, for example, is filled with naturally heated reservoirs that circulate by pipe to keep virtually every home in the country cozy. And in Kenya and New Zealand, geothermal aquifers supply the heat used in industrial processes, including for pasteurizing milk and making toilet paper.

Bezner Kerr and I, however, stood atop a multilayered cake of mudstone, limestone, sandstone, and other rocks — seemingly everything but water. To access the heat radiating beneath our feet, his team will need to create artificial reservoirs more than 2 miles into the earth.

America’s geothermal industry has made significant strides in recent years to generate clean energy in less obvious locations, and it’s done so by adapting tools and techniques from oil and gas drilling. One leading startup, Fervo Energy, is developing “enhanced geothermal systems” in Utah and Nevada to produce clean electricity around the clock. The approach involves fracking impermeable rocks, then pumping them full of water so that the rocks heat the liquid, which eventually produces steam to drive electric turbines.

Earth Source Heat plans to use similar methods to drill a handful of super-deep wells and create fractures near or within the crystalline basement rock, where temperatures are consistently around 180 degrees Fahrenheit, no matter the weather above. The project is also unique in that, among next-generation systems, it’s focused only on heating buildings — not supplying electricity — for the nearly 30,000 students and faculty. That’s because heat represents the biggest source of Cornell’s energy use, and its largest obstacle to reducing planet-warming emissions.

On the chilliest days, the campus can use up to 104 megawatts of thermal energy, which is more than triple its peak use of electrical energy during the year.

Such a ratio poses a big conundrum for not only large institutions like Cornell but also any cold-climate cities that burn fossil fuels to keep warm, as well as manufacturing plants that require lots of steam and hot water for steps as varied as fermenting beer, making oat milk, and sterilizing equipment.

Right now, one of the most immediate ways to cut emissions from thermal energy use is to replace gas-fired boilers and the like with heat pumps and other electrified technologies. But that can substantially increase a city’s or factory’s electricity use. In an ideal world, all the new power demand would be satisfied by renewable energy projects and served by a modern and efficient grid, helping limit the costs and logistical headaches of ditching fossil fuels.

In reality, though, the U.S. electricity system is straining to keep up with the emergence of data centers, new factories, and electrified buildings and vehicles. Utilities are pushing plans to build new gas-fired power plants and proposing higher electricity rates to cover the costs. New York, for its part, is failing to meet its own goals for installing gigawatts of new renewables and energy storage projects by 2030, in part because of barriers to permitting projects in the state. New York’s independent grid operator recently warned of “profound reliability challenges” in coming years as rapidly growing demand threatens to outpace supply.

Geothermal heating could provide a way to curb thermal-energy emissions without burdening the electric system even more, said Drew Nelson, vice president of programs, policy, and strategy with Project InnerSpace, a nonprofit that advocates for geothermal energy use.

“Electrification is great, but that’s a whole lot of new electrons that need to be brought onto the grid, and a whole lot of new transmission and distribution upgrades that need to be made,” Nelson said by phone. “For applications like industrial heat, or building heating and cooling, geothermal almost becomes a ‘Swiss Army knife,’ in that it can help reduce demand.” Using geothermal energy directly is also far more efficient than converting it to electricity, since a lot of energy gets lost in the process of generating electrons.

Still, deep, direct-use geothermal systems like the one Cornell is developing are relatively novel, and many manufacturers and city planners are either unfamiliar with the solution or unwilling to be early adopters.

Sarah Carson, the director of Cornell’s Campus Sustainability Office, explained that Earth Source Heat is intended to reduce technology risks and costs for other major heat users that might benefit from geothermal, including the region’s dairy producers and breweries. We spoke inside her office, which is attached to the 30-megawatt gas-fired cogeneration plant that currently provides both electricity and heating for the campus.

“We’re working really hard to build a ‘living lab’ approach into the ethos of how we approach things,” she said. “Can we not only take care of our own [carbon] footprint but also help develop and demonstrate solutions that could scale out?”

Earlier on that overcast day, Bezner Kerr and I drove to the shores of Cayuga Lake.

Winds whipped up the grayish-blue waters, which form one of the 11 long, skinny Finger Lakes that glaciers etched into the Earth millions of years ago. Cayuga Lake is, in a way, the inverse of a heated geothermal reservoir. Cornell uses the chilly lake to cool the water that circulates across campus, replacing the need for industrial chillers that use lots of refrigerants and electricity.

Inside the Lake Source Cooling facility, giant blue pipes intersect through pieces of equipment called heat exchangers. Since heat naturally flows from hotter objects to colder ones, the lake water acts like a magnet, pulling heat out of the campus-water loop. The lake-water loop then moves the heat down to the cold bottom of Cayuga, and the cycle repeats. Bezner Kerr said Earth Source Heat will do the same but in reverse, flowing hot water up to the surface and returning the cooled-off water underground, where the earth can continuously reheat it.

Initially, he said, the new geothermal system will connect to an existing underground hot-water loop that heats East Campus, including two energy-intensive research buildings. This first stage is expected to cost over $100 million and could be completed in the next few years. Depending on how Earth Source Heat performs, the university might expand the system to warm around 150 large buildings on the main campus.

The university’s approach is far more intensive than the geothermal systems that cities and high-rise buildings are increasingly deploying across the country. An underground thermal network in Framingham, Massachusetts, consists of 90 holes drilled about 650 feet deep that heat 36 homes and commercial buildings; it also uses electric heat pumps to boost the temperatures coming out of the ground. Cornell’s home city of Ithaca has proposed piloting its own thermal network to heat and cool buildings on a city block.

Jefferson Tester, a Cornell professor and the principal scientist for Earth Source Heat, said these shallower geothermal systems aren’t as practical for heating the 15-million-square-foot campus.

For one, the university would need to drill north of 10,000 smaller wells to adequately warm all its buildings, instead of the five very deep wells it has planned. And digging deeper into the ground will allow Cornell to use the heat straight away, without adding heat pumps.

Tester joined Cornell in 2009 to help launch Earth Source Heat, which is part of the university’s larger plan to achieve a carbon-neutral campus in Ithaca by 2035. For over a decade, faculty and engineers gathered data and developed models to get a better sense of the region’s geology, heat resources, and potential for drilling-related earthquakes, often in partnership with the U.S. Department of Energy.

But to fully grasp the subsurface’s conditions, they needed to drill. “And once you understand the geology well enough … you could go anywhere in this region” to harness geothermal energy, Tester said.

In 2022, the university drilled that first 10,000-foot-long hole, which is called the Cornell University Borehole Observatory, in the parking lot. “It was the same level of intensity as an oil-and-gas exploration rig,” Bezner Kerr recalled. “It was oil-and-gas workers drilling a well that produces knowledge instead of producing hydrocarbons.” Cornell received about $7 million from the Energy Department for the project, which cost around $14 million to deploy.

Now the team is ready to drill again, though the timing of the next phase is up in the air amid funding uncertainty.

Earth Source Heat wants to reopen the borehole, deepen it, and use fiber-optic cables and other tools to study how the rock responds to stress and high-pressure injections of water — data that will inform the design of the final system. In 2024, during the Biden administration, Cornell applied for over $10 million from the Energy Department for the project, with plans to line up drilling equipment this year. But the Trump administration hasn’t yet responded to the request.

If the team can finish the second phase of its borehole observatory, the next step will be to drill a demonstration well pair — two vertical spines with horizontal legs, and fractured rocks in between — to begin heating part of East Campus.

The drilling delays come as Cornell faces growing criticism from climate activists both on and off campus, who argue that the university isn’t reducing its emissions nearly fast enough to help limit global temperature rise. Cornell on Fire, a climate-justice group, has raised concerns that Cornell is using Earth Source Heat as a “delay tactic to avoid undertaking necessary actions now on other critical fronts.” The group says Cornell should immediately provide more adequate funding for the geothermal project and be more transparent about its timeline for implementing the system.

Meanwhile, Carson said her office is feeling pressure from climate advocates to start replacing the current gas-fueled heating network with electrified technologies like heat pumps and electric boilers. But she and her colleagues believe that swiftly boosting Cornell’s electricity demand would require increasing gas-fired power generation off campus, reducing the school’s CO2 footprint on paper without lowering emissions overall. Even so, Carson’s team is evaluating a range of potential solutions, including heat-storing batteries and shallower geothermal networks, in case Earth Source Heat doesn’t work as well as hoped.

These tensions highlight the tricky reality of developing big and novel clean-energy projects. A well-designed, smartly managed geothermal system could help decarbonize heat for buildings and factories over the course of many decades. But finding the right locations and best ways to install those networks takes careful planning, patience, and significant upfront investment. That can be tough to stomach, both for project investors antsy to see financial returns and for citizens eager to dump polluting fossil fuels today.

“We’ve got to be thinking about a long-term, multigenerational commitment” for tackling climate change, Tester said. “And that is really hard for people.”

To Bezner Kerr, it doesn’t seem like larger discussions on decarbonization fully acknowledge just how big of a challenge heat represents — and what it would mean to electrify all the country’s heating needs. We were speaking then in his office, where a grayish chunk of Potsdam sandstone retrieved from deep below sat in a white plastic bucket next to his desk.

“It’s like there’s this huge train coming down the tracks,” he said. “And nobody realizes we’re about to get flattened by this thing if we do it wrong.”

A correction was made on Dec. 10, 2025: This story originally misstated Cornell on Fire’s position on the Earth Source Heat project; this piece has been updated to more accurately reflect the group’s stance.

In the waning days of Governor Phil Murphy’s tenure, New Jersey officials unveiled an updated Energy Master Plan that calls for 100% clean electricity by 2035 and steep reductions in climate pollution by midcentury. Since 2019, the state has used the first version of the plan as the backbone of its climate strategy, promising reliable, affordable, and clean power.

The blueprint lands at a moment when delivering on all three goals is increasingly in doubt.

While the second Trump administration rolls back federal clean-energy support, PJM Interconnection, the regional grid operator that serves New Jersey and a dozen other states, struggles to manage surging electricity demand from artificial intelligence data centers.

“The Energy Master Plan is a statutorily required report to chart out New Jersey’s energy future,” said Eric Miller, who leads the Governor’s Office of Climate Action and the Green Economy. While not binding, it is the state’s official roadmap to attain its climate goals.

Miller’s office and the state Board of Public Utilities developed the plan with public input and help from outside consultants.

Under the plan, New Jersey is betting heavily on utility-scale solar and battery storage. State modeling envisions total solar capacity climbing to about 22 gigawatts by 2050, which is four times today’s roughly 5 gigawatts of installed solar. On paper, it would be enough to supply nearly all the state’s current households over a year. To get there, the plan assumes adding about 750 megawatts of new solar each year from 2026, roughly double the pace of solar construction in 2024.

The plan’s release follows a governor’s race in which energy costs dominated, and voters chose U.S. Rep. Mikie Sherrill, a Democrat who campaigned on preserving Murphy-era climate targets, over Jack Ciattarelli, a Republican who argued for a slower transition.

“Voters sent a clear message that clean energy is the most cost-effective path forward and the smartest long-term investment,” said Ed Potosnak, head of the New Jersey League of Conservation Voters and a local council member in Franklin Township.

The plan lands as New Jersey enters what Miller calls the “load-growth era.”

For roughly two decades, electricity demand in PJM’s footprint, which stretches from New Jersey to Illinois, was flat or falling as aging power plants retired and efficiency improved. That trend has flipped because of data centers.

“What we saw in 2024 into ’25, and I think what we’re going to see for the next 15 years, is a scenario where demand on the electric grid is growing,” Miller said.

For years, New Jersey spent billions subsidizing hundreds of thousands of electric vehicles and thousands of buildings to electrify. Now, Miller said, “some of the techniques for greenhouse gas reductions are going to have to kind of meet the moment,” by taking a more proactive role in engaging with PJM or by filling in the dearth in clean energy incentives caused by the Trump administration.

The recent PJM capacity auctions have added billions of dollars in costs for customers across the region. This showed up as a 20% jump in summer electricity bills in New Jersey this year, which became a hot campaign issue during its recent gubernatorial race.

“The wholesale price of electricity is determined by PJM and federal policy, and then also the price of natural gas,” said Frank Felder, an energy economist who has advised regulators. “New Jersey can’t do much about that.”

Participating in a fast-track rulemaking process that PJM initiated to address data center–driven demand, outgoing governor Murphy joined other governors in proposing that data center developers bring their own power generators in exchange for quicker permit processing.

PJM seeks to decide which proposals to pursue this month and file them with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission by the end of the year.

Layered on top of PJM’s turmoil are decisions coming from Washington.

Experts repeatedly pointed to President Donald Trump’s second-term moves to strip away clean-energy tax incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act and to impose new tariffs on imported solar panels and wind equipment. They say those steps have raised costs and driven off developers.

Potosnak called it “Trump’s clean energy ban” and said the administration’s opposition to offshore wind “derailed the best chance we had to get massive amounts of offshore wind going that would have begun lowering our utility rates this year.” Several major Atlantic projects, including those planned off New Jersey’s coast, have been canceled or delayed.

Offshore wind “was a big piece of trying to get to 100% clean electricity by 2035,” Felder said. With new contracts unlikely for several years, he warned that New Jersey could be “back at basically square one” by the end of the decade.

Even so, Felder and others urged caution against writing off renewables entirely. Robert Mieth, a Rutgers University researcher who studies power systems, noted that offshore wind is well established in Europe and that, with or without U.S. manufacturing, “there will be access to competitive and affordable renewable technology from other countries.”

In the meantime, state officials point to progress in areas they can influence more directly.

Miller noted that New Jersey has gone from roughly 20,000 plug-in vehicles in 2018 to about 270,000 today, after lawmakers set clear targets and funded incentives and chargers.

The state’s “nation-leading solar program,” he said, is “primarily state-incentivized, primarily state-funded,” and it can keep expanding — albeit more slowly now — even as federal tax credits expire.

“The cheapest energy is the energy you don’t have to make,” Potosnak said, citing efficiency programs, rooftop and warehouse solar, and batteries on parking lots that “drive down utility costs for families and businesses” while cutting pollution.

For all its detail, the Energy Master Plan is not binding.

“The Energy Master Plan does not have the force of law,” Miller said. It has been “very informative,” he added, but “it is not a legal requirement that we follow it exactly.”

Gov.-elect Sherrill will determine how closely New Jersey hews to the map. Neither she nor her opponent had any role in shaping the modeling, Miller said, and the plan was not written with a particular “political future” in mind. Instead, Miller said, the Murphy administration hopes the incoming governor will treat it as “a very useful modeling exercise” or a guide.

Advocates are already trying to lock some of those targets into a statute. Potosnak’s group is backing a lame-duck bill that would incorporate the state’s 2035 goal of 100% clean energy — currently in place from a 2023 Murphy executive order — into state law.

If it passes, he said, it would give residents and environmental groups the right to sue if future administrations fall short and send a signal to investors that New Jersey’s direction will not change with every election.

The New York Power Authority approved a plan Tuesday to nearly double the state-owned utility’s goal for solar, wind, and energy storage projects to 5.5 gigawatts. The new investments would boost clean power in the state as the private market fails to deploy renewable energy fast enough to meet New York’s lofty decarbonization goals.

In a unanimous decision, the board of trustees voted to greenlight the utility’s new strategic plan for renewables. Though the 5.5 GW figure is an increase over the utility’s initial plan, released this January, it also represents a reduction from the 7 GW draft plan NYPA unveiled over the summer.

The utility blamed the slimmer target on private renewable-energy developers pulling out of 16 joint ventures. Activists, however, accused NYPA of dropping projects to boost plans for new fossil-fuel infrastructure recently approved by Gov. Kathy Hochul, a Democrat.

The 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act requires New York to generate 70% of its power from renewables by 2030 and the rest of its electricity from zero-carbon sources by 2040. It’s one of the most ambitious decarbonization goals in the country, but the state is lagging behind on meeting its legally mandated benchmarks in virtually every category of clean power except for distributed energy sources that include rooftop solar.

Today, natural-gas-fired power stations provide about half New York’s electricity. Aging hydroelectric stations, backed up by additional dams in Canada, provide nearly one-quarter of the state’s power, closely followed by nuclear reactors from plants upstate. Solar and wind each account for only a single-digit share of the state’s power mix, below the U.S.-wide share and far below that of California, Texas, and other states.

NYPA, the second-largest state-owned utility after the federal Tennessee Valley Authority, is increasingly being called on to help close that gap.

Two years ago, Hochul approved measures to give NYPA a mandate to invest directly in clean energy projects — an authority modeled closely on a piece of legislation called the Build Public Renewables Act.

This January, NYPA unveiled a plan to build out more than 3 GW of wind, solar, and batteries using its expanded remit. In July, it released a draft plan that more than doubled that target to 7 GW

But NYPA, required by law to take majority stakes in the developments it backs, elected to own just 51% of these projects. So when developers backed out of the 16 joint ventures, due largely to the rollback of federal tax credits for wind and solar projects and a lack of available transmission capacity, NYPA said it was forced to move forward with fewer projects.

In a statement cautioning that the strategic plan “is an iterative document that will be continually re-assessed and updated,” NYPA’s chief executive Justin Driscoll called the latest proposal “a strong portfolio of refined project opportunities that builds on the energy capacity outlined in the inaugural plan.”

“Despite strong headwinds threatening the viability of renewables projects throughout the nation, NYPA continues to leverage its expertise and reputational strength to develop projects that will bolster the energy diversity of New York’s electric grid,” Driscoll said. “This updated plan is only a snapshot of our ongoing efforts, and NYPA will continue to assess the state’s addressable renewables market to identify new projects that can be added into future plans.”

While the state’s climate law sets deadlines for New York to up the share of renewables in its power mix, NYPA is not beholden to completing the full 5.5 GW by a specific date. The plan, though scheduled for an update only every two years, could be revised as early as next year as new projects become viable or existing ones go under.

The finalized plan drew sharp criticism from Public Power New York, a left-wing group that campaigned for the Build Public Renewables Act. Rather than cut back, the group said, NYPA should expand its target to 15 GW of solar, wind, and batteries. The organization helped marshal more than 10,000 public comments supporting the higher-end goal.

In an interview, Public Power New York’s co-chair Michael Paulson accused Hochul of deliberately dampening the state’s renewables potential to bolster the controversial Williams Companies gas pipeline into New York City, a project The New York Times reported would benefit clients of the law firm that employs the governor’s husband, William Hochul.

“This is unfortunately part of a pattern,” Paulson said. “Instead of using the tools to build a more affordable and better future, Hochul is pushing toxic fossil-fuel projects to enrich her utility donors and potentially even enrich her own family.”

In an email, Hochul’s office called the claims “both disingenuous and ludicrous.”

“NYPA’s plan represents a realistic strategy, as required by law, to build out a portfolio of new renewables,” Ken Lovett, a spokesperson for the governor, told Canary Media. “Under Governor Hochul’s leadership, New York continues to be a national clean energy leader. In the face of federal and economic roadblocks, and warnings of energy shortages downstate as soon as next summer, the Governor’s all-of-the-above energy agenda is designed to keep the lights on and costs down.”

In a June press release, Public Power New York also slammed Hochul and NYPA’s plan to build at least 1 GW of new nuclear power upstate by the time New York’s climate law requires a fully decarbonized system in 2040, calling the effort a distraction from wind and solar.

While Paulson acknowledged the real bottleneck the transmission system poses, he criticized the governor for not doing more to approve new power lines and said her administration should support more distributed solar and batteries in the region facing the state’s worst electricity shortages: New York City and its surrounding suburbs.

Paul Williams, the founder and executive director of the Center for Public Enterprise, a think tank that favors expanded state capacity, agreed New York lawmakers need to do more to make building transmission lines — a challenge everywhere in the U.S. — easier.

“What this strategic plan makes clear is that while NYPA was planning on more renewables projects, there are interconnection barriers that are keeping them from moving forward faster,” Williams said. “The question for those of us who want to see NYPA succeed and build more public renewables is, What can we do to help NYPA overcome interconnection barriers? The faster we can help solve that bottleneck, the faster we can build these projects.”

An update and a clarification were made on December 9, 2025: A statement from Gov. Kathy Hochul’s office was added to this piece, and the story has been changed to make clear that NYPA is required by law to take a majority stake in the projects it backs

President Donald Trump’s freeze on approvals of new wind energy projects has been deemed “unlawful” in a federal court.

On Monday, Judge Patti B. Saris of the U.S. District Court in Massachusetts ruled in favor of 18 state attorneys general who had challenged the temporary ban on onshore and offshore wind permitting, which has been in place since Trump issued an executive order on his first day in office.

Led by New York, the coalition of states and the District of Columbia was joined by the Alliance for Clean Energy New York, a nonprofit advocacy group based in Albany. The lawsuit cited, among other things, harms caused by a stop-work order that paused construction of New York’s Empire Wind 1 in April, which had cited the president’s executive order. (The pause was later reversed after a lobbying blitz.)

The attorneys general also claimed that the wind ban on new projects on federal lands and waters impeded their ability to “lower energy costs” and “reduce greenhouse gas emissions” through wind energy generation.

States with ambitious offshore wind plans were especially hard-hit. Almost all offshore projects are built in federal waters, where the government acts as a kind of landlord. The executive order halted seven offshore wind projects that were in the process of being permitted and several others in earlier stages of development, according to data collected by Canary Media from the federal permitting dashboard. In total, roughly 40 offshore wind leases are scattered across the waters offshore of Maine down to the Carolinas, across the Gulf of Mexico, and along the California coast.

Saris ruled that the executive order was “arbitrary and capricious” on multiple grounds. For example, the Department of the Interior had failed to provide a “reasoned explanation” for suddenly changing course from the decades-long practice of issuing wind permits.

“Whatever level of explanation is required when deviating from longstanding agency practice, this is not it,” wrote Saris, referring to four paragraphs of Trump’s presidential memo, which were the basis of the lawsuit.

The ruling is the latest in a series of major losses for the Trump administration as it seeks to defend the president’s anti-wind agenda in court. Last week, a federal judge denied the government’s attempt to revoke approvals for US Wind, a project slated to be Maryland’s first offshore wind farm. In September, a federal judge ruled in favor of the Danish energy giant Ørsted, whose $6.2 billion New England offshore wind project was halted by the Interior Department, which cited the executive order to justify the move but, as the judge put it, didn’t provide any“factual findings.”

The government had defended the order as temporary, pending the completion of a review of permitting and leasing practices. Federal lawyers argued that this assessment was “underway” but submitted no documents to the court to support such claims. Saris struck down this argument, blasting the review for having “no anticipated end date” and creating the risk of a de facto indefinite permitting moratorium.

A former Interior Department official who spoke with Canary Media on the condition of anonymity said that there was little evidence that the agency had even initiated this kind of review, at least within the first half of the year.

“We were ready to support a review at any time we were asked,” said the staffer, who has since left the agency, adding that “no formal request” to start the review described in the presidential memo ever reached the desks of career federal employees.

The Interior Department was not the only agency that harmed the embattled offshore wind sector in the name of Trump’s “day one” order.

The Environmental Protection Agency in March revoked an essential Clean Air Act permit from Atlantic Shores, an offshore wind development slated to be built off the New Jersey coast, using the order as one of the main justifications. An EPA decision based on little more than Trump’s direction — essentially a presidential memo — raised eyebrows among experts.

“It’s not unprecedented,” Stan Meiburg, a former acting deputy administrator of the EPA, told Canary Media, referring to the use of a presidential order to revoke an EPA permit.“But it still seems unusual that you would cite it that heavily in a case.”

Even with the wind order now set aside, the federal government is unlikely to start approving wind farms anytime soon. There is little legal precedent for courts compelling agencies to issue permits. And some see the damage done by Trump’s “unlawful” order as irreversible.

“It’s sad,” said a current Interior Department staffer, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution, but discussed with Canary Media how the permitting freeze had prompted many wind companies to lay off staff and hit the brakes on projects that were years in the making.

“All the regulatory uncertainty … I think that is the goal that this department and this administration is trying to put forward,” said the staffer.

New Haven, Connecticut, has broken ground on an ambitious geothermal energy network that will provide low-emission heating and cooling to the city’s bustling, historic Union Station and a new public housing complex across the street.

The project will play a crucial role in the city’s attempt to decarbonize all municipal buildings and transportation by the end of 2030. As one of Connecticut’s first geothermal energy networks, it will also serve as a case study of how well the technology can both lower energy costs and reduce greenhouse gas emissions as the state considers promoting wider adoption of these systems.

“At the end of the day, you’re going to have the most efficient heating and cooling system available for our historic train station as well as roughly 1,000 units of housing,” said Steven Winter, New Haven’s executive director of climate and sustainability. “Anything we can help do to improve health outcomes and reduce climate change–causing emissions is really valuable.”

In climate-conscious states across the country, thermal energy networks are emerging as a promising way to reduce reliance on fossil fuels for heating, lower utility bills, and create a pathway for the gas industry to transition its business model for a cleaner-energy future. These neighborhood-scale systems use ground-source heat pumps and a web of underground pipes to deliver heating and cooling to connected buildings.

The thermal energy for heating can come from a variety of sources, including geothermal systems, industrial waste heat, and surface water. Because no fossil fuels are directly burned to produce heat, the only emissions are those created generating the electricity to run the network. At the same time, the systems insulate customers from volatile and rising natural gas prices.

“There’s a lot of excitement around networked geothermal because it actually offers solutions to a lot of problems,” said Samantha Dynowski, state director of Sierra Club’s Connecticut chapter. “It can be a more equitable solution for a whole neighborhood, a whole community — not just a single home.”

The practice of deploying such systems as a neighborhood loop is relatively new, but the component parts are well established: Geothermal heat pumps have been around for more than 100 years, and the pipe networks are very similar to those used for natural gas delivery.

“The backbone technology is the same kind of pipe you use in the gas system,” said Jessica Silber-Byrne, thermal energy networks research and communications manager for the nonprofit Building Decarbonization Coalition. “They’re not experimental. This isn’t an immature technology that still needs to be proved out.”

There are a handful of networked geothermal systems around the United States, owned by municipalities, private organizations, and universities. A couple of miles away from the Union Station project, at Yale University, development is underway on a geothermal loop serving several science buildings.

But the idea is catching on among gas utilities, too. The nation’s first utility-owned geothermal network came online in Framingham, Massachusetts, in June 2024, and just received an $8.6 million federal grant that will allow it to double in size. Across the country, 26 utility thermal energy network pilots are underway, and 13 states have passed some form of legislation exploring or supporting the approach, according to the Building Decarbonization Coalition.

In Connecticut, a comprehensive energy bill that passed earlier this year established a grant and loan program to support the development of thermal energy networks. Advocates are now pushing Gov. Ned Lamont, a Democrat, to issue the bonds needed to fund the new initiative.

The New Haven network could provide a concrete example of the opportunities offered by such systems.

The plan began when the federal government was seeking applications for its Climate Pollution Reduction Grant program, an initiative created by President Joe Biden’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. Union Station seemed like an excellent property to retrofit because of its age, its size, and its prominent role in the city: Nearly a million travelers pass through the station each year, making it one of Amtrak’s busiest stops and an excellent platform for demonstrating the potential of geothermal networks.

“We thought it would be a powerful message to send for this beautiful landmark building that’s also the gateway to the city,” Winter said.

In July 2024, the federal program awarded the proposal just under $9.5 million; though there were questions earlier in the year about whether the Trump administration would attempt to block the money, the grant program ultimately proceeded. Planners expect federal tax credits and state incentives to cover the remaining $7 million in the project budget.

The network will use as many as 200 geothermal boreholes. Fluid will circulate through pipes in each of these wells, picking up thermal energy stored within the earth; in hotter weather, when cooling is needed, the systems will transfer energy back into the ground.

The city began drilling the first test boreholes in November. The results were promising: One test hole was able to extend down 1,200 feet, significantly farther than the 850 feet projected, Winter said. If more boreholes can be drilled that deep, it could mean fewer holes are needed overall — and thus less materials — making the project more efficient, he said.

Construction of the network is still in the early stages. The test boreholes should be completed this month, and the design of the ground heat exchanger — the underground portion of the system in which the thermal energy is transferred — is about halfway done, Winter said. The city is also preparing to accept proposals for the retrofit of the heating and cooling systems in the station itself.

The goal is to have the system up and running in the latter half of 2028. The apartment units, which are still in the design phase, will be connected to the system as they are built.

Even as the initial plan comes together, New Haven is already considering the possibility of expanding the nascent network to include more buildings, such as other apartment units under development nearby, existing buildings in the neighborhood, and a police station around the corner, Winter said.

“Ideally, we end up with a municipally owned thermal utility that can help decarbonize this corner of the city and provide affordable, clean heating and cooling,” he said.

Since spring of last year, North Carolina’s largest utility has been testing whether household batteries can help the electric grid in times of need — and now the company wants to roll out the plan to businesses, local governments, and nonprofits, too.

Duke Energy has already paid hundreds of North Carolinians to let it tap power from their home storage systems when electricity demand is highest. It’s Duke’s first foray into running a “virtual power plant,” in which the company manages electricity produced and stored by consumers, much as it would control generation from its own facilities.

In September, the utility proposed a similar model for its nonresidential customers, asserting that the scheme will save money by shrinking the need for new power plants and expensive upgrades to the grid. The recognition signals a way forward for distributed renewable energy and storage as state and national politicians back away from the clean energy transition.

The initiative now needs approval from the five-member North Carolina Utilities Commission, where the virtual-power-plant model has faced some skepticism. But the apparent merits of Duke’s plan, which has broad backing, may be too enticing for commissioners to ignore — especially when the state is grappling with rising rates and voracious demand from data centers and other heavy electricity users.

“In an era of massive load growth, something that should lower costs to customers while helping meet peak demand — to me, it’s an absolute no-brainer,” said Ethan Blumenthal, regulatory counsel for the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, an advocacy group. “I’m hopeful that [regulators] see it the same way.”

Duke’s trial residential battery incentives grew out of a compromise with rooftop solar installers. Like many investor-owned utilities around the country, the company sought to lower bill credits for the electrons that solar owners add to the grid. When the solar industry and clean energy advocates fought back, the scheme dubbed PowerPair was born.

The test program provides rebates of up to $9,000 for a battery paired with rooftop photovoltaic panels. It’s capped at roughly 6,000 participants, or however many it takes to reach a limit of 60 megawatts of solar. Half of the households agree to let Duke access their batteries 30 to 36 times each year, earning an extra $37 per month on average; the other half enroll in electric rates that discourage use when demand peaks.

The incentives have been crucial for rooftop solar installers, who’ve faced a torrent of policy and macroeconomic headwinds this year, and they’ve proved vital for customers who couldn’t otherwise afford the up-front costs of installing cheap, clean energy.

But the PowerPair enrollees already make up 30 megawatts in one of Duke’s two North Carolina utility territories and could hit their limit in the central part of the state early next year, leaving both consumers and the rooftop solar industry anxious about what’s next.

Duke’s latest proposal for nonresidential customers — which, unlike the PowerPair test, would be permanent — is one answer.

The proposed program is similar to PowerPair in that it’s born of compromise: Last summer, the state-sanctioned customer advocate, clean energy companies, and others agreed to drop their objections to Duke’s carbon-reduction plan under several conditions, including that the utility develop incentives for battery storage for commercial and industrial customers. The Utilities Commission later blessed the deal.

“This was pursuant to the settlement in last year’s carbon plan,” said Blumenthal, “so it’s been a long time coming.”

While many industry and nonprofit insiders refer to the scheme as “Commercial PowerPair,” its official title is the Non-Residential Storage Demand Response Program.

That name reflects the incentives’ focus on storage, with solar as only a minor factor: Duke wants to offer businesses, local governments, and nonprofits $120 per kilowatt of battery capacity installed on its own and just $30 more if it’s paired with photovoltaics.

The maximum up-front inducement of $150 per storage kilowatt is much less than the $360 per kilowatt offered under PowerPair. But more significant for nonresidential customers could be monthly bill credits: about $250 for a 100-kilowatt battery that could be tapped 36 times a year, plus extra if the battery is actually discharged.

Unlike households participating in PowerPair, which must install solar and storage at the same time to get rebates, nonresidential customers can also get the incentives for adding a battery to pair with existing solar arrays.

“That could be very important for municipalities around North Carolina that have already installed a very significant amount of solar, but very little of that is paired with battery storage,” said Blumenthal.

Duke has high hopes for the program, projecting some 500 customers to enroll. Five years in, the resulting 26 megawatts of battery storage would help it avoid building nearly 28 megawatts of new power plants to meet peak demand, saving over $13.6 million. That’s significantly more than the cost of providing and administering the incentives, which Duke places at nearly $11.8 million.

“The Program provides a source of cost-effective capacity that the Company’s system operators can use at their discretion in situations to deliver economic benefits for all customers,” Duke said in its September filing to regulators. “Importantly, the Company received positive feedback from its customers … when sharing the details of the Program.”

Indeed, the proposal has been met with support not just from the Sustainable Energy Association and other clean energy groups but also organizations like the North Carolina Justice Center, which advocates for low-income households. It earned praise from local governments represented by the Southeast Sustainability Directors Network and conditional support from the state-sanctioned customer advocate, known as Public Staff, too.

The good vibes continued last week, when Duke responded positively to detailed suggestions from these parties on how to improve the program. That included a request from Public Staff that the company raise the per-customer limit on battery capacity to align with the maximum amount of solar that a business or other nonresidential consumer can connect to the grid, which is currently 5 megawatts.

“Larger batteries sited at larger customer sites can help provide more significant system benefits and can reduce the need for incremental utility-owned energy storage installed at all ratepayers’ expense,” the agency told regulators in its November comments. It recommends a cap tied to a customer’s peak demand; for example, a business that consumes more energy at once should get incentives for a bigger battery. Duke agreed in its Dec. 5 comments, calling that limit “reasonable.”

Still, questions remain about how to make the incentives most impactful.

Public Staff, for instance, believes Duke should increase its monthly payment to customers for keeping their batteries charged and ready to deploy. This “capacity credit” is now set at $3.50 per kilowatt but effectively reduced to $2.48, because the utility assumes that a percentage of users won’t properly maintain their systems, based on its experience with households. The company calls that a “capability factor,” but the agency dubs it “collective punishment” for all customers and says it should be eliminated or recalibrated for “more sophisticated” nonresidential participants.

Raleigh, North Carolina–based 8MSolar, a member of the Sustainable Energy Association, is among the many installers that have been eagerly anticipating Duke’s proposal.

The program on its own likely won’t “move the needle unless the incentives get bumped up,” said Bryce Bruncati, the company’s director of sales. However, the scheme could tip the scales for large customers when stacked on top of two federal tax opportunities: a 30% incentive available through the end of 2027 and a deduction tied to the depreciation value of the system — up to 100% thanks to the Republican budget law passed this summer.

“The combined three could really have a big impact for small- to medium-sized commercial projects,” Bruncati said. The Duke program would represent “a little bit of icing on the cake.”

Whatever their size and design, the fate of the incentives rests entirely with the Utilities Commission, now that the final round of comments from Duke and other stakeholders is in. There’s no timeline for a decision.

At least one commissioner, Tommy Tucker, has voiced skepticism about leveraging customer-owned equipment to serve the grid at large. “I’m not a big fan of the [demand-side management] or virtual power plants because you’re dependent upon somebody else,” the former Republican state senator said at a recent hearing, albeit one not connected to the Duke program.

Still, Blumenthal waxes optimistic. After all, Tucker and three other current members of the commission are among those who ruled last year that Duke should present the new incentive program.

“They seem to recognize there is value to distributed batteries being added to the grid,” Blumenthal said. “The fact that [the proposal] is cost-effective is key because the idea is, the more of it you do, the more savings there are.”

Two corrections were made on Dec. 10, 2025: This story originally misstated the number of times a year that Duke can tap a PowerPair participant’s battery; it is 30 to 36 times a year, not 18. The story also originally misstated the enrollment Duke expects for the nonresidential program; the utility expects 26 megawatts of batteries, not 26,000 customer participants.

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the week” column.

If you had to guess which country gets the largest share of its electricity from solar, you might understandably toss out the name of a balmy island nation. Or perhaps you’d pick a country with swaths of blistering desert. At the very least, somewhere notoriously hot and sunny. Right?

Well, you would be wrong. The global leader is Hungary, according to a recent report from think tank Ember that pulls from full-year 2024 data and only considers nations that generated over 5 terawatt-hours of solar.

The Central European country got nearly one-quarter of its electricity from solar panels last year, leapfrogging Chile, which had held the top spot since 2021. Hungary’s win is no fluke: From January through October this year, solar grew to account for about one-third of power generated in the nation of 10 million.

It’s quite the shift. Just five years ago, Hungary got only 7% of its power from solar. Ember attributes the rapid growth to robust policies supporting both utility-scale and residential installations.

Rounding out the top five countries on Ember’s list are Greece, Spain, and the Netherlands. The top 10 is dominated by countries in the European Union, which is chipping away at coal- and gas-fired electricity.

To be clear, Hungary is not producing more electrons with solar panels than any other country. That distinction goes to China, which generates far more terawatt-hours’ worth of clean power than anywhere else, even if it only gets about 8% of its electricity from solar.

We’ll check back in next year to see if Hungary has retained its improbable title. The competition will be stiff. After all, the solar boom is a worldwide phenomenon.

Big companies have spent years pushing Georgia to let them find and pay for new clean energy to add to the grid, in the hopes that they could then get data centers and other power-hungry facilities online faster.

Now, that concept is tantalizingly close to becoming a reality, with regulators, utility Georgia Power, and others hammering out the details of a program that could be finalized sometime next year. If approved, the framework could not only benefit companies but also reduce the need for a massive buildout of gas-fired plants that Georgia Power is planning to satiate the artificial intelligence boom.

Today, utilities are responsible for bringing the vast majority of new power projects online in the state. But over the past two years, the Clean Energy Buyers Association has negotiated to secure a commitment from Georgia Power that “will, for the first time, allow commercial and industrial customers to bring clean energy projects to the utility’s system,” said Katie Southworth, the deputy director for market and policy innovation in the South and Southeast at the trade group, which includes major hyperscalers like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft.

The terms of the commitment were first sketched out in a letter agreement between Georgia Power and CEBA last year and then codified in a July settlement agreement between the utility, staff at the Georgia Public Service Commission, and other stakeholders that cemented the utility’s long-term integrated resource plan.

The “customer-identified resource” (CIR) option will allow hyperscalers and other big commercial and industrial customers to secure gigawatts of solar, batteries, and other energy resources on their own, not just through the utility.

Letting data centers procure their own energy resources could solve a lot of problems for utilities — like the risk of sticking their customers with the cost of building power plants that may be unneeded if the AI boom goes bust. That’s a real concern for Georgia Power, which plans to spend more than $15 billion to build 10 gigawatts of new gas plants and batteries by 2031. This move could dramatically increase customers’ bills and is almost entirely motivated by gigantic — yet highly uncertain — projections of how much energy that data centers will need.

The tech giants behind most of those data centers could also benefit from being able to track down their own clean energy. The carbon-free resources would not only help in meeting hyperscalers’ aggressive climate targets; they are also likely to be cheaper and faster to build than gas plants, which face yearslong backlogs and rising costs.

The CIR option isn’t a done deal yet. Once Georgia Power, the Public Service Commission, and others work out how the program will function, the utility will file a final version in a separate docket next year.

And the plan put forth by Georgia Power this summer lacks some key features that data center companies want. A big point of contention is that it doesn’t credit the solar and batteries that customers procure as a way to meet future peaks in power demand — the same peaks Georgia Power uses to justify its gas-plant buildout.

But as it stands, CEBA sees “the approved CIR framework as a meaningful step toward the ‘bring-your-own clean energy’ model,” Southworth said — a model that goes by the catchy acronym BYONCE in clean-energy social media circles.

The CIR option is technically an addition to Georgia Power’s existing Clean and Renewable Energy Subscription (CARES) program, which requires the utility to secure up to 4 gigawatts of new renewable resources by 2035. CARES is a more standard “green tariff” program that leaves the utility in control of contracting for resources and making them available to customers under set terms, Southworth explained.

Under the CIR option, by contrast, large customers will be able to seek out their own projects directly with a developer and the utility. Georgia Power will analyze the projects and subject them to tests to establish whether they are cost-effective. Once projects are approved by Georgia Power, built, and online, customers can take credit for the power generated, both on their energy bills and in the form of renewable energy certificates. Georgia Power’s current plan allows the procurement of up to 3 gigawatts of customer-identified resources through 2035.

Letting big companies contract their own clean power is far from a new idea. Since 2014, corporate clean-energy procurements have surpassed 100 gigawatts in the United States, equal to 41% of all clean energy added to the nation’s grid over that time, according to CEBA. Tech giants have made up the lion’s share of that growth and have continued to add more capacity in 2025, despite the headwinds created by the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress.

But most of that investment has happened in parts of the country that operate under competitive energy markets, in which independent developers can build power plants and solar, wind, and battery farms. The Southeast lacks these markets, leaving large, vertically integrated utilities like Georgia Power in control of what gets built. Perhaps not coincidentally, Southeast utilities also have some of the country’s biggest gas-plant expansion plans.

A lot of clean energy projects could use a boost from power-hungry companies. According to the latest data from the Southern Energy Renewable Association trade group, more than 20 gigawatts of solar, battery, and hybrid solar-battery projects are now seeking grid interconnection in Georgia.

“The idea that a large customer can buy down the cost of a clean energy resource to make sure it’s brought onto the grid to benefit them and everybody else, because that’s of value to them — that’s theoretically a great concept,” said Jennifer Whitfield, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, a nonprofit that’s pushing Georgia regulators to find cleaner, lower-cost alternatives to Georgia Power’s proposed gas-plant expansion. “We’re very supportive of the process because it has the potential to be a great asset to everyone else on the grid.”

Isabella Ariza, staff attorney at the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal Campaign, said CEBA deserves credit for working to secure this option for big customers in Georgia. In fact, she identified it as one of the rare bright spots offsetting a series of decisions from Georgia Power and the Public Service Commission that environmental and consumer advocates fear will raise energy costs and climate pollution.

“They’re proposing something that makes total sense and would help some companies be able to say ‘We’re powering our stuff with 100% clean energy,’” Ariza said of the CIR option. That’s particularly important at a time when many hyperscalers are backing away from their clean energy targets in their hunt for power for AI data centers, she noted.

Despite those benefits, the CIR framework’s omissions are substantial enough that CEBA did not join stakeholders like Walmart, the Georgia Association of Manufacturers, and the Southern Renewable Energy Association trade groups in signing on to it.

CEBA wanted companies to be able to procure a full range of carbon-free generation resources — such as geothermal and small modular nuclear reactors — rather than just renewable energy and renewables paired with batteries. The trade group also sought a pathway for customers to bring projects forward on a rolling basis more quickly than the current settlement agreement would allow.

But one of the biggest issues CEBA has with the current CIR plan is that it “does not recognize the full capacity value of customer-funded clean, firm resources to the grid,” Southworth said. Capacity value is a measure of how power plants, batteries, and other resources meet peak power demands during the handful of hours per year that determine how much generation and grid infrastructure utilities need to build.

That’s a significant gap. If the resources that big customers secure under the CIR aren’t considered part of the solution to this challenge — if their capacity value isn’t factored in — they may not be able to reduce Georgia Power’s need for gigawatts of gas-fired power plants, which are the traditional utility backstop for ensuring adequate energy supplies.

This would be bad for Georgia Power customers at large, who would end up paying for more gas plants than are actually needed after the data centers driving up power demand secure their own resources instead. It could also saddle data centers and other big customers with growing capacity-related costs that their self-secured projects could otherwise help reduce.

“A well-designed CIR program that recognizes the capacity value of customer-funded clean resources is a win-win-win for large customers, Georgia Power, and all ratepayers,” Southworth said. “Participating customers pay the incremental cost of new clean, firm projects; the utility gets capacity it can count on; and nonparticipating customers benefit from a more diverse, less gas-dependent resource mix without taking on the full cost or fuel price risk of those projects.”

CEBA has ideas for how Georgia Power could financially compensate customers for the capacity value of the resources that they procure. The utility already calculates “avoided capacity values” for the renewable energy, battery, and fossil-fueled resources it brings to the table in its requests for proposals. Georgia Power could provide a capacity credit of similar value to subscribing customers for the projects they procure.

CEBA will “continue to work with the company and commission staff,” Southworth said. Her group sees Georgia Power’s long-term plan approved this summer “as establishing the floor, not the ceiling, for what CIR can become.”

A big shift at the Public Service Commission could lay the groundwork for a reassessment of the program. Last month, Georgia voters elected two Democratic challengers — health care consultant Alicia Johnson and clean-energy advocate Peter Hubbard — to replace Republican incumbents Tim Echols and Fitz Johnson.

The two new commissioners have both pledged to tackle high and rising electricity costs for Georgia Power residential customers. Across the country, utilities and regulators are striving to force data center developers to take on the costs they’re imposing on power grids, rather than foisting them on everyday utility customers.

“Capacity is still an open question” that the Public Service Commission can take up as it decides on the CIR option, said Whitfield of the Southern Environmental Law Center. “Georgia Power is certainly on record that they don’t prefer it to be accredited, which makes sense for them. They want to build more and profit more,” as a regulated utility that earns guaranteed profits on its capital investments. “But that is going to be very much a live issue.”