Exxon Mobil has pulled the plug on what would have been one of the world’s largest hydrogen plants, the latest setback for the effort to scale production of low-carbon versions of the fuel.

In 2022, the oil giant announced plans to build a facility at its refining and petrochemical complex in Baytown, Texas, with the capacity to produce 1 billion cubic feet per day of so-called blue hydrogen, which is made using natural gas and carbon-capture equipment. It won a nearly $332 million grant from the Biden administration’s Department of Energy to finance the project.

But the Trump administration yanked that funding this spring. Since blue hydrogen typically costs about one-third more than the “gray” version of the fuel made with unmitigated gas, Exxon Mobil CEO Darren Woods said the company could not find enough buyers willing to pay the premium.

“There’s been a continued challenge to establish committed customers who are willing to provide contracts for off-take,” Woods said in an interview with Reuters.

Exxon Mobil Corp. did not return Canary Media’s call Wednesday requesting comment.

The pullback highlights mounting problems for the clean hydrogen industry. Green hydrogen, the zero-carbon version of the fuel made with clean electricity and water, costs even more than the blue or gray types. In October, the Trump administration terminated federal funding for two regional hydrogen hubs on the West Coast that were meant to help bring down the cost of the green fuel. Blue hydrogen, in theory, was seen as less politically vulnerable since its production ensures a market for gas. But that, too, now appears to be running into similar problems.

“Exxon’s decision reflects a broader reality: Large-scale hydrogen projects depend on long-term market signals, stable policy environments, and customers ready to commit,” said Roxana Bekemohammadi, the founder and executive director of the United States Hydrogen Alliance, an industry group. “These dynamics take time to mature.”

But it’s not just the Energy Department’s decision to shutter its Industrial Demonstrations Program, which had given Exxon Mobil the grant, and the cuts to the 45V federal tax credits, which support low-carbon hydrogen production, that have put the industry on shaky ground.

Trump administration moves have also undermined demand for low-carbon hydrogen. In October, the U.S. government thwarted an effort at the United Nations’ International Maritime Organization to put a price on carbon emissions from the shipping sector, pressuring foreign delegates to back off a proposal that would have expanded the market for low-carbon hydrogen.

Blue hydrogen also faces some specific headwinds.

Late last month, the European Parliament passed legislation outlining rules for low-carbon hydrogen that require producers to demonstrate not only that carbon-capture equipment catches at least 70% of emissions but also “pretty rigorous accounting of upstream methane leakage,” according to Pete Budden of the Natural Resources Defense Council. A study published last year in the International Journal of Hydrogen Energy found that carbon-capture equipment could reduce emissions by 60%, below the threshold set in the European Union law.

“Based on the work we’ve done tracking emissions from blue hydrogen, it’s going to be really tough for U.S. hydrogen producers to meet that reduction with fossil fuels and [carbon capture and storage],” said Budden, the lead hydrogen advocate at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “It’s a really ambitious emissions reduction because you need a really, really high capture rate, and you need to minimize all your upstream leakage.”

In the U.S., California remains the biggest market for the fuel. While state regulators slashed their 2030 forecast for hydrogen-powered vehicles, a giant power plant in Los Angeles just received approval to convert from gas to hydrogen.

“Yes, there have been significant reductions to federal funding for programs. Yes, we took a hit this year. Yes, it caused uncertainty in the markets. And yes, it caused some projects to pause,” said Katrina Fritz, the chief executive of the California Hydrogen Business Council, the nation’s largest and oldest statewide trade group for the fuel. “But in California, we still have offtake markets that are moving forward. There’s still demand. And we still have new production projects moving forward.”

Among those projects: a solar-powered green hydrogen facility. Its owner? Chevron.

This story was first published by Grist.

Phillip Stafford has been converted. After two years of driving a Tesla, he says there’s no going back to gasoline — the money he saves on fuel alone makes that clear. And since his work as a crisis counselor takes him all over Richmond, Virginia, he charges often.

That’s made him picky about where he buys electrons. On a crisp fall afternoon last month, Stafford had his Model 3 plugged in at a Sheetz. A red-and-white Wawa sandwich wrapper on the seat hinted at where his heart lies in that convenience-store rivalry. Still, brand loyalty goes only so far when the battery is running low. Given a choice between the two, Sheetz wins. “It has more watts, so it charges a little faster,” he said.

The seemingly small question of where to spend 20 or so minutes topping off a battery reveals the transformation taking hold among fuel retailers. For more than 50 years, chains like Wawa, Sheetz, and Love’s Travel Stops have defined when and where people refuel. As EVs reshape mobility, these retailers are among those embracing charging.

Their challenge goes beyond providing power to turning the time that drivers spend plugged in into profitable foot traffic. Selling electricity alone won’t pay the bills; the real money lies in selling snacks. Making that work requires reimagining what a pit stop looks and feels like, even as costly infrastructure upgrades and shifting federal policies complicate the transition.

Wawa and Sheetz are two of the furthest along. The Pennsylvania-based companies have built out hundreds of chargers and enjoy fervent fanbases that make them two of the most popular convenience stores in the country. Their made-to-order sandwiches, vast array of snacks, and clean restrooms have made them regular stops for road trippers and commuters alike — and now, for EV drivers looking to recharge their cars and, often, themselves.

They offer a glimpse of the road ahead. As electric vehicles move ever further from niche toward norm, the focus for retailers like these could shift from which one offers the cheapest fuel to which one can make waiting for the car to fill up the best experience.

“The problem with a lot of current gas stations is [they’re] not that nice of a place to spend 15, 20, or 30 minutes,” said Scott Hardman of the Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, Davis. “Hopefully in the future, we’ll see more of them turn into coffee shops, cafes — places you actually want to be.”

That future is slowly coming into focus. Retailers like Wawa and Sheetz have spent the past few years exploring what the transition from selling gasoline to selling electricity might look like. Even with the headwinds EVs face, at least 26 percent of cars on U.S. roads could be electric by 2035, and some projections suggest they could account for 65 percent of all sales by 2050.

The two chains offer a place to plug in at over 10 percent of their locations. Wawa has installed more than 210 chargers, while Sheetz provides more than 650 at 95 locations that have logged at least 2 million sessions. Clean amenities and expansive menus with offerings like Wawa’s turkey-stuffed Gobbler and Sheetz’s deep-fried Big Mozz have placed them near the top of convenience store satisfaction rankings.

Both say embracing cars with cords builds on what already attracts customers. Wawa frames it as an extension of its “one-stop” model for food and fuel. Its competitor calls charging “a seamless extension of the Sheetz experience.” The language differs, but the message is the same: Selling electricity works if it brings people like John Baiano inside.

The New York resident owns two Tesla Model Ys and travels throughout the northeast for his two businesses — a Bitcoin consultancy and a horse racing operation. He plugs in at Wawa because the stores are clean, offer plenty of amenities, and provide a comfortable place to check in with clients. “I use the bathroom, maybe get a snack,” he said. (He prefers the turkey pinwheel.) “I was a little nervous about the charging aspect of things. Once I started experiencing this, it was seamless.”

At the moment, most public quick chargers are tucked away in the far corners of shopping centers, inside parking garages, and other functional but hardly inviting places to spend 20 minutes. They’re fine when you’re out and about running errands, but not terribly appealing at night and not particularly conducive to a road trip.

Tesla dominates the space with its Supercharger network, which provides over half the country’s quick chargers, with Electrify America, EVgo, and ChargePoint together accounting for another 25 to 30 percent. Retailers like Love’s Travel Stops, Pilot Flying J, and Buc-ee’s are joining Sheetz and Wawa in working with those networks and others to add chargers alongside gas pumps. Their efforts signal how a system built for gasoline is starting to evolve for electricity.

Everything Stafford and Baiano like about plugging in at a convenience store reflects an Electric Vehicle Council study that ranked security, lighting, and 24/7 access as the three things drivers want most in a charging station. Another survey found that 80 percent of them will go out of their way to get it. Reliability is another concern — and a frequent complaint with the nation’s current charging infrastructure. As EVs become more common, drivers are going to be less willing to put up with malfunctioning or broken chargers than the early adopters were.

Ryan McKinnon of the Charge Ahead Partnership, which pushes for a comprehensive charging network, sees fuel retailers as a logical place to build out such a system because they already have the right locations and amenities. “What EV charging needs is a competitive and lucrative marketplace where folks can actually make money selling EV charging,” he said.

Therein lies the challenge. Buying and installing a quick charger can cost more than $100,000. Beyond that lie fluctuating prices from utility companies, which one leading charging provider said is a key factor in deciding where to locate the devices. Retailers won’t recover that by selling electrons alone, given that the machines might generate just $10,000 in revenue each year, Hardman said. EVgo noted in its second-quarter earnings report that it earned just under $12,000 per stall.

Making this work for retailers requires getting people out of their cars and into the stores. Just as gas retailers earn two-thirds of their profit selling sandwiches, snacks, and sodas, those selling electricity can expect to do the same. Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that installing an EV charger increased spending by 1 percent, which would cover 11 percent of the cost of installing the charger. (Other studies have found similar benefits for surrounding businesses; Tesla Superchargers can boost revenue by 4 percent.)

For some retailers, chargers are a loss leader meant to pull customers into stores, said Karl Doenges of the National Association of Convenience Stores. Others see them as a way to secure increasingly scarce electrical capacity while it’s available. Some are moving “forward on a charging station, even though they don’t think [the market is] 100 percent ready,” he said.

Even the strongest business cases for installing the devices depended on Washington’s help to pencil out. Incentives that the Biden administration created through the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law provided billions in grants, tax credits, and matching funds to help expand the fueling infrastructure of tomorrow, particularly in rural and low-income communities that a free market might overlook.

When Donald Trump won the 2024 presidential election, there was little doubt federal support for this ambitious effort would change. Yet the upheaval was more dramatic than expected. In February, the Trump administration paused the $5 billion National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure, or NEVI, program, the backbone of Washington’s effort to build a nationwide charging network. Fuel retailers, which have been some of the effort’s biggest beneficiaries, expressed concern.

The administration reluctantly reinstated NEVI, which had installed just 126 charging ports by the time Trump won his second term, in August. “If Congress is requiring the federal government to support charging stations, let’s cut the waste and do it right,” Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy said at the time. But with most of the funding allocated, the program will likely expire in 2026.

When it revived NEVI, the Trump administration updated recommendations for states, which administer the funds, in a way that seems to favor a national network run by big chains with highway operations. The Federal Highway Administration’s guidance explicitly recommended building charging infrastructure near fuel retailers.

Nonetheless, at least some of those companies see this as a difficult moment for EV charging. Joe Sheetz, executive vice chairman of the family-owned company, has said momentum is slowing because much of the funding has come from the government and big players like Tesla. Some smaller chains are backing away, but Sheetz said his company will keep at it.

Even as EV adoption grows, most people will continue to plug in largely at home. About 80 percent of charging occurs there, and some providers, like It’s Electric, are skipping partnerships with fuel retailers, focusing instead on slower and cheaper level 2 chargers that are convenient for apartments or homes without garages and do the job in four to 10 hours.

Charles Gerena, a lead organizer of the advocacy organization Drive Electric RVA, rarely visits a public charger in his Chevy Bolt. But on longer trips, he’s noticed more opportunities to plug in, especially in rural areas where fast charging was once scarce. On a recent road trip to Virginia Beach in his wife’s Ford Mustang Mach-E, he took advantage of the car’s ability to tap the Tesla Supercharger network and used the app PlugShare to find a reliable station — at a Wawa.

“I like Wawa’s food better than Sheetz,” he said. “I think I’m in the minority. My daughter actually likes Sheetz better.” Still, for Gerena, reliability trumps loyalty. “If it gets a lousy rating, I’d be wary of going to it, regardless of which gas station it was.”

Despite customer loyalty that can sometimes divide households, retailers are learning that sandwiches and snacks aren’t enough. Success will depend on providing plenty of opportunities to plug in, and making sure the hardware works when drivers need it.

The world is clamoring for more electrons. It’s getting them from solar and wind.

Between January and September, the two clean-energy sources grew fast enough to more than offset all new demand worldwide, according to data from energy research firm Ember.

Power demand rose by 603 terawatt-hours compared to that same time period last year. Solar met nearly all that new demand on its own, increasing by 498 TWh. Wind generation, meanwhile, climbed by 137 TWh.

What happens when clean energy not only meets but exceeds new power demand? We start to burn less fossil fuels. At least a little less: Through Q3, fossil-fuel generation dropped by 17 TWh, compared to the first three quarters of 2024. This trend is expected to continue through the end of the year. Ember forecasts that fossil-fuel generation will have experienced no notable growth in 2025 — something that hasn’t happened since the height of the Covid-19 pandemic.

It’s unclear whether this flatlining marks the beginning of the end for fossil-fueled electricity or whether it’s just a pause before another surge in dirty power. The answer will more or less be determined by what grows faster: electricity demand or renewable energy.

Common consensus is that the world’s appetite for electricity will expand rapidly in the coming years. The planet is warming and driving increased use of air conditioning. AI developers are building massive power-hungry data centers. Cars, homes, and factories are being electrified. That all adds up: The International Energy Agency expects power demand to rise by a staggering 40% over the next decade.

Meanwhile, it’s almost not worth considering long-term forecasts about the growth of clean energy, given how inaccurate they’ve been in the past. Analysts have consistently underestimated solar, in particular.

For the global power sector to truly decarbonize, carbon-free energy needs to not only keep pace with electricity demand but far outrun it. Let’s hope solar continues to overperform.

Over the past decade or so, the Connecticut Green Bank, the first green bank in the United States, has taken on an unusual role — that of a “public developer” of solar projects for schools, cities, and low-income housing across the state.

“There are all sorts of public institutions that take in public money and give a loan, a grant, and that’s all they do,” said Jason Kowalski, executive director of the Public Renewables Project. “This is completely different in what it can achieve.”

The Connecticut Green Bank’s Solar Marketplace Assistance Program Plus (Solar MAP+) actively engages in originating, developing, and even owning projects, he said. To date, the program has deployed $145 million in capital on nearly 54 megawatts’ worth of solar projects that are expected to help save a collective $57 million in energy costs, according to bank data shared with Canary Media.

Though the approach is unusual for a public entity, it needn’t be, Kowalski said. In fact, it is a model that cash-strapped state governments should consider closely as federal clean-energy tax credits disappear and energy costs rise. That’s particularly true for the 16 states, plus the District of Columbia, that have created a government-backed or nonprofit green bank since Connecticut first launched its version in 2011.

The bank’s program targets sectors that private lenders and solar developers might shy away from because of perceived credit risks or low returns on investment, Kowalski explained. It taps into low-cost financing available to state entities and builds portfolios of projects to achieve economies of scale.

Then the revenues generated from those projects are “recycled”: used to expand the pool of capital from which it can make loans for other projects that help achieve Connecticut’s clean energy and environmental justice goals.

While some private-sector solar industry players may see the Solar MAP+ approach as infringing on their turf, state-backed agencies “see it as expanding the role of the private-sector installation business,” Kowalski said.

That’s certainly the case for the school solar projects that Solar MAP+ has built, said Tish Tablan, senior program director at Generation180, a clean energy advocacy group.

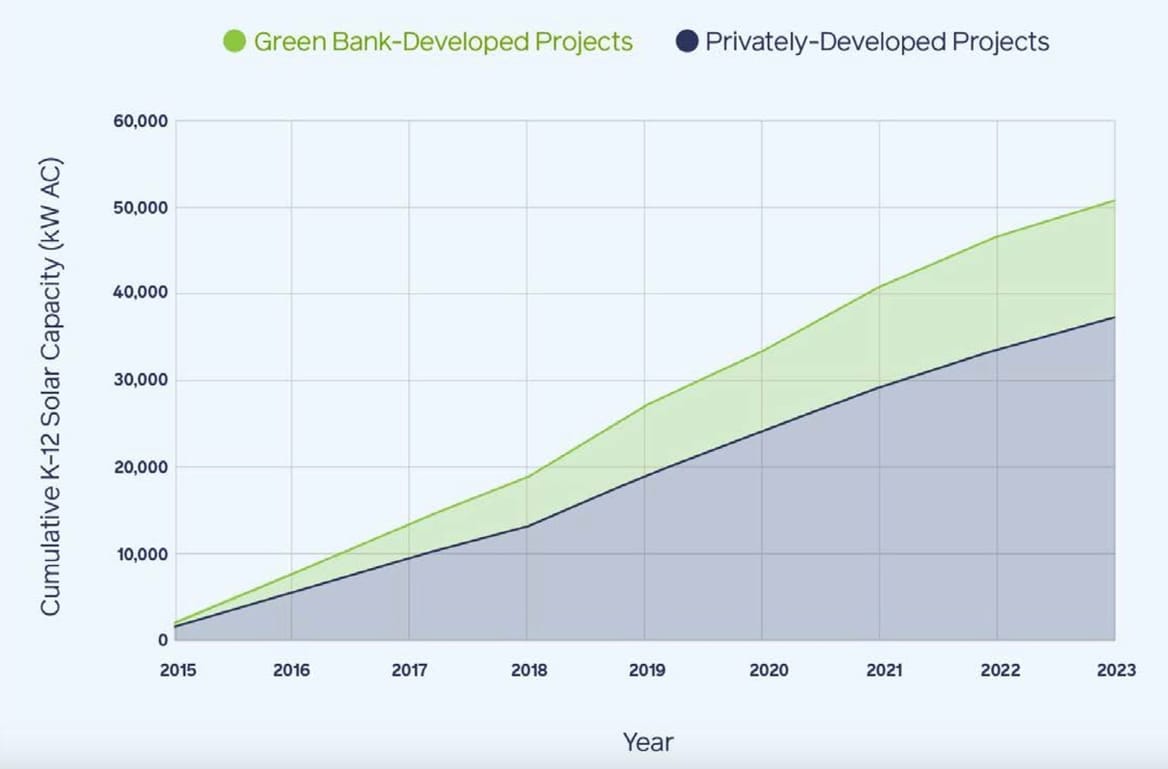

A September report by Tablan’s and Kowalski’s groups and the Climate Reality Project found that Connecticut — the third-smallest state by land mass and 29th in population — ranks fifth in the country for total solar capacity installed on K–12 schools and second (behind Hawaii) in the percentage of K–12 schools with solar.

The Connecticut Green Bank developed 27% of school solar installations in the state from 2015 to 2023, according to the report. Those installations are projected to save schools tens of millions of dollars in energy costs, and more than half are in low-income and disadvantaged communities.

The same model can help schools and public buildings do more than solar, Tablan added. “We can look at electrification, we can look at heat pumps, we can look at solar-plus-storage, we can look at microgrids.”

This kind of financial support is increasingly important as the Trump administration cancels federal funding for clean energy projects more broadly, and in disadvantaged communities in particular, Tablan and Kowalski said. That includes the administration’s move to claw back $20 billion in federal “green bank” funds meant to promote precisely this kind of public-sector finance, which is now being challenged in court.

Solar MAP+ evolved largely as a response to gaps in the state’s broader solar market, said Mackey Dykes, the Connecticut Green Bank’s executive vice president of financing programs.

The same 2011 law that launched the bank also created state solar incentives meant to boost development across multiple sectors of the economy, Dykes said. “But there were some areas where we didn’t see a lot of activity. We sat down and started to figure out why that was.”

The first targets were state agencies that were lagging in solar development, despite their access to relatively low-cost capital, he said. This indicated that incentives alone weren’t the solution. It turned out that those agencies “needed help with documentation structures, with procurement, with project labor agreements,” he said. “We put that together, and projects started happening.”

“Then we realized we built this Swiss Army knife of tools that we could bring to bear in other sectors where there were gaps in solar deployment,” Dykes said. The Connecticut Green Bank also started looking at municipalities that were lagging in using solar incentives, particularly smaller towns, he said. At around the same time, he noted, “we realized the solar incentive program in the state was undersubscribed for school projects,” and they set out to fix that.

Bundling multiple school projects can help lower costs. Dykes cited the example of a 67-kilowatt system at an intermediate school in Portland, Connecticut. “You’d have trouble attracting attention for a project that small,” he said. “When you combine it with dozens of projects, and have developers competing with a pool of projects, the projects become more feasible,” with the Connecticut Green Bank serving as a clearinghouse for hiring installers and securing financing at a larger scale.

Tablan highlighted the similarities with Generation180’s work with schools. “If you ask any public-sector entity, they’re going to say budget and cost are the first concerns,” she said. Most of the country’s school solar projects have been developed via third-party ownership models, and “Connecticut Green Bank has taken that approach” as well, she said.

The wraparound services that Solar MAP+ offers bring more than money to the equation, said Advait Arun, senior associate for capital markets at the Center for Public Enterprise. The nonprofit think tank uses the term “public development” to characterize the way public entities can expand beyond financing to include “all of the steps in a project development pipeline,” including ownership, operations, and maintenance.

That’s not a normal role for green banks, Arun said. As of the end of 2023, green banks and partners had driven a cumulative $25.4 billion in public and private investments, according to the Coalition for Green Capital, a group that includes green banks and environmental advocacy organizations. Most of that funding has focused on de-risking harder-to-finance sectors, such as energy efficiency and rooftop solar installations in low-income neighborhoods, without taking the plunge into the full range of project development activities that Solar MAP+ is involved in.

But even under this model, there are gaps that private sector financiers don’t want to fill. That’s where public-sector ownership can help, as the data on school solar’s growth in Connecticut indicates, Arun noted.

“We’re not used to this kind of thing in this country,” he said. But “without the Connecticut Green Bank de-risking schools for this kind of solar investment, the market would have remained smaller than it could be.”

That direct involvement has helped smaller school districts build more ambitious project pipelines over time, said Emily Basham, director of financing programs for Solar MAP+.

In Manchester, Connecticut, once the private developers caught wind of state involvement, city leaders “were somewhat bombarded with proposals,” Basham said. “They wanted to do their first projects with us, to cut their teeth on it.”

The more than $100,000 in projected annual energy savings from the solar systems at seven municipal buildings, including six schools, helped the city gain confidence in moving forward with a subsequent project that has converted one of its elementary schools into the state’s first net-zero school by adding advanced insulation systems and on-site geothermal energy, she said.

The Connecticut Green Bank’s dive into parts of the project development process has drawn fire from solar industry groups in the state.

In 2024, solar developers pushed lawmakers to restrict the bank from developing projects at schools and municipal sites, citing concerns around a lack of competitive bidding. That effort was defeated after representatives of state and local government as well as labor and clean-energy advocates at the Connecticut Roundtable on Climate and Jobs weighed in to support the bank.

Some of those supporters came from Branford, Connecticut, which contracted with the Connecticut Green Bank to build solar arrays on two elementary schools.

“We’re a municipality with limited staff and dedicated volunteers, but you can’t ask volunteers to procure and oversee a project of that size,” said Jamie Cosgrove, who recently ended a 12-year stint as Branford’s first selectman — the equivalent of the town’s mayor — to join the Connecticut Green Bank’s board of directors. “We use them as a trusted source, and we feel comfortable engaging with them to move forward on a number of these projects.”

The two elementary schools’ solar installations are expected to save about $248,000 over the next 20 years, Cosgrove noted — not a huge payback for a private-sector developer. “Maybe these projects aren’t significantly cash-flow positive. But there are other priorities we have as a municipality. We’re looking to advance our clean energy goals.”

Branford has also done plenty of work with the private sector, including a 4.3-megawatt solar array on a former gravel yard and solar projects at the town’s high school and fire station, said Jim Finch, Branford’s finance director. “It’s not an either-or thing,” he said.

“I don’t think it’s unreasonable for a state entity that’s identified reducing carbon emissions as a public purpose to do this kind of work,” Finch added. “We have organizations to deal with clean air, financing sewer projects, et cetera — we can have public purpose entities do that.”

State development finance agencies — government entities in all 50 states that support economic development through a variety of financing structures — could also take on this kind of public developer model, he said.

New York could be a first target, said Kowalski of the Public Renewables Project. The New York Power Authority, the public agency that owns and develops transmission and generation in the state, has been tasked with building gigawatts of large-scale renewables. Backers of more muscular government intervention to rejuvenate the state’s faltering progress on clean energy are calling for the NYPA to follow Connecticut’s lead in building solar on school rooftops.

Finding ways to push more finance into solar projects has become a more pressing matter, Kowalski said, both to offset the loss of solar tax credits from the megalaw passed by Republicans in Congress this summer and to combat fast-rising electricity costs across the country.

“Our whole report is an answer to how to respond to the tax credits getting rolled back. If there’s a shortfall, we think we have an answer,” Kowalski said. “Public developer models can be part of an affordability agenda on climate.”

DALLAS — The automated machinery and bright, clean factory floor wouldn’t look out of place in the solar manufacturing hub of Changzhou, China. But every so often, the pristine industrial order was punctuated by, of all things, carrier robots blasting psychedelic rock as they rolled down the aisles.

T1 Energy runs this half-mile-long factory just 15 miles south of Dallas, where seven parallel manufacturing lines produced more than 20,000 photovoltaic modules on the day I visited in October. After ramping up in the early months of 2025, T1 is on track to produce up to 3 gigawatts this year, but with the systems dialed in and workers operating 24/7, the facility has been running fast enough to make 5 gigawatts in a year, said Russell Gold, executive vice president for strategic communications.

The factory is finding its legs just as the Trump administration vaporizes pro–clean energy policies and instead pursues a fossil-heavy vision of “energy dominance.”

“What the manufacturers here really want, and really need, is just certainty,” said MJ Shiao, vice president of supply chain and manufacturing at the trade group American Clean Power. What they got this year was “policy whiplash,” he said, which has caused the Biden-era drumbeat of clean-energy manufacturing announcements to morph into a chorus of cancellations, per data from Atlas Public Policy.

But T1 nonetheless is staking a claim to homegrown American solar energy and making the case that it’s still lucrative. The firm has plowed ahead this year, signing deals for U.S.-made polysilicon and U.S.-made steel frames and preparing to build its own solar-cell fabrication facility.

Gold pointed to the booming demand for solar, which has become the biggest source of new power plant capacity getting built in the U.S. today by a long shot.

“We absolutely believe that it is a great time to be making solar,” said Gold, who came to T1 in May after a career covering energy for The Wall Street Journal. “The main reason is we’re in the middle of this massive trend toward more electricity usage … Solar is the scalable energy resource that can produce the amount of electricity that is demanded today.”

T1’s facility bustles with robots and people working side by side.

Autonomous units ferry materials around and handle the heavy lifting of pallets stacked high with finished panels. Specialized machines cut cells and string them together with electrically conductive filaments, while others sandwich rows of cells between glass, snap their frames into place, and roll them through a high-temperature curing process.

Today those frames are made out of imported aluminum, but next year T1 will replace them with U.S.-made steel frames from Nextpower, the solar equipment juggernaut formerly known as Nextracker. Dan Shugar, Nextpower’s CEO, had visited T1 shortly before I did; given Shugar’s well-known love for classic guitar rock, technicians reprogrammed the autonomous guided vehicles’ warning sounds with grooves by Santana and AC/DC. (“Because of course, AC/DC — it’s appropriate,” Gold told me.) The sounds stuck around.

The factory was running two 12-hour shifts every day, with workers watching over the robots and stepping in when necessary to correct their work. Signs listed every key notice in English, Mandarin, and Spanish, and the 1,200-person workforce reflected the diversity of the Texas metropolis.

The only production line that wasn’t operating during my visit had been geared toward smaller residential panels. T1 had paused production in response to slack demand, Gold said, and was working to adjust the line to produce panels for the booming utility-scale market instead.

Around the factory, a few clues hinted at a more nuanced backstory than the triumphal, homegrown American solar narrative that T1 leads with. Much of the production machinery sported the logo of Trina Solar, a Chinese company that ranks among the most prolific solar manufacturers in the world. At the end of the tour, we surveyed the warehouse area, where pallets of finished modules awaited shipping in Trina Solar–branded cardboard boxes.

The Chinese company, in fact, built the factory, as part of a wave of foreign investment in U.S. solar panel assembly that kicked off back in 2018, when the first Trump administration levied new tariffs on Chinese imports. Chinese investment in U.S. solar factories accelerated considerably when the Biden administration passed industrial policy that rewarded manufacturers for U.S. production and developers for installing domestically made equipment.

Within two and a half years of Biden signing the Inflation Reduction Act, the U.S. built enough factories to assemble all the panels it needed. The entire supply chain had not been re-shored, but it was well on its way — a remarkable turnaround for a sector long since decimated by cheaper Chinese competition. The lone exception to that collapse was First Solar, which makes a thin-film cadmium-telluride panel, in contrast to the dominant silicon-based photovoltaics; that company, too, has expanded its U.S. footprint, recently completing a factory in Louisiana and announcing a new one in South Carolina.

Even before Trump won his second election, though, bipartisan political sentiment was shifting against Chinese companies’ benefiting from federal incentives, even those that built state-of-the-art factories in the U.S. and staffed them with American workers.

Trina had constructed the Dallas factory and had just begun the laborious process of commissioning the lines when it evidently saw the writing on the wall. Trina sold the factory in December to Freyr Battery, which had tried and failed to build battery gigafactories in Norway and Georgia. The entity officially rebranded as T1 Energy in February and now is headquartered in the U.S. and traded on the New York Stock Exchange.

Gold demurred on the question of who approached whom with an offer. In any case, after the transaction, T1 owned the factory, which it calls G1 Dallas, and Trina retained a 13.2% stake in the company. That arrangement neatly anticipated the “foreign entity of concern” (FEOC) rules that Trump signed into law this summer: Republicans restricted clean energy tax credits from going to companies with too much ownership by Chinese companies.

“FEOC is going to be a challenge for this industry because China has dominated the solar industry for years,” Gold said. But the December transaction took the factory from a level of Chinese ownership that would violate the subsequent FEOC rules to a level “well below the equity cutoff,” Gold noted. “We were doing it before Congress spelled out what people need to do.”

Congress set the FEOC restrictions to kick in at the start of 2026, which means some domestic solar factories will, ironically, cease to qualify for the made-in-America tax credits under their current ownership structures. Santa’s sack just might hold some factories for corporations, like T1, that have made it onto the FEOC “nice list.”

As for the ongoing use of Trina-branded containers for shipping T1 modules, “there was no reason to make extra waste by trashing a bunch of boxes,” Gold said.

Solar panels are the last step of the supply chain, and the one with the lowest barrier to entry: Though highly specialized and automated, the machines at T1, as at Qcells’ facility in Dalton, Georgia, are assembling components produced elsewhere. Making silicon cells requires a step change in capital and technical proficiency, as do the precursor steps of producing wafers and polysilicon ingots.

The U.S. has proved it can make solar panels that, if not economically competitive with those made in China, can get by in a protectionist trade regime that, at least for now, is still buoyed by federal incentives. Cell production is ticking up in the U.S., which currently has factories that can use them — Suniva and ES Foundry each brought about 1 gigawatt of cell capacity on line in the past year. Qcells is finishing up a 3.3-gigawatt cell-production facility in Georgia.

This constitutes an “orderly strategic buildout” for the domestic industry, said Shiao of American Clean Power. “The cell producers aren’t going to come until the module producers come … Right now, we’re starting to see that larger growth of cell production because we’ve had those years for those investment decisions to come to fruition.”

T1 is also getting in on the photovoltaic-cell action. By the end of the year, Gold said, the company expects to break ground on a $400 million cell-fabrication plant, or fab, in Rockdale, Texas, down the road from another silicon-oriented business: a major Samsung chip-fab development. The plan is to ramp up to 2.1 gigawatts of cell production by the end of 2026 and add another 3.2 gigawatts in a subsequent phase.

That’s one angle. This fall T1 also bought a minority equity stake in a fellow upstart solar manufacturer called Talon PV, which is building a 4.8-gigawatt cell fab in Baytown, Texas, and targeting production in early 2027.

Until those factories open, T1 is importing cells from non-FEOC countries, Gold said.

A T1 deal with legacy glass producer Corning signals a further deepening of the U.S. solar supply chain. Corning announced in October that it had opened polysilicon ingot and wafer production in Michigan — the crucial precursor to cell production, and something the U.S. hasn’t had in almost a decade. Business launched on an auspicious note, as Corning has already sold 80% of all its expected production for the next five years to customers including T1.

With that industrial breakthrough, the pieces have fallen into place for a fully American supply of the key silicon solar-panel components. Now the question is whether this fledgling supply chain can survive the tumultuous policy swings of the second Trump presidency.

Around the world, smelters use massive amounts of electricity — often generated by fossil fuels — to turn raw materials into aluminum. As more carbon-free energy comes onto the grid, these power-hungry facilities will get progressively cleaner. But smelters will never be entirely emissions-free until producers can solve a much trickier technical problem.

That’s because modern aluminum plants rely on a 19th-century process that uses big blocks of carbon, which account for almost one-sixth of the greenhouse gases associated with producing new aluminum globally. Replacing the blocks is crucial to decarbonizing this key industrial process.

Now the industry may be one step closer to reaching that goal.

Earlier this month, the Canadian firm Elysis said it hit a major milestone when it deployed an industrial-size, carbon-free anode inside an existing smelter in Alma, Quebec. Elysis is a joint venture of the U.S. aluminum giant Alcoa and global mining company Rio Tinto, both of which produce aluminum in the Canadian province.

“This is really a first for the aluminum industry, and a worldwide first as well,” François Perras, president and CEO of Elysis, told Canary Media.

Elysis installed its “inert,” or chemically inactive, anode technology in a 450-kiloampere (kA) cell, the same amount of electric current used in many large, modern smelters. The full-scale prototype is a significant step up from the company’s 100 kA pilot unit, which has produced low-carbon aluminum used in certain Apple laptops and iPhones, Michelob Ultra beer cans, and the wheels for Audi’s electric sports car.

Elysis launched in 2018 and has raised over 650 million Canadian dollars ($460 million) in investment for the effort, including from the governments of Canada and Quebec. The 450 kA cell will undergo several more years of testing as the company works to measure and validate how the larger unit performs inside a commercial smelter.

Rio Tinto, meanwhile, has already licensed the inert-anode technology from Elysis. The manufacturer plans to build a demonstration plant with 10 of the 100 kA cells at its existing Arvida smelter in Quebec, possibly by 2027, through a joint venture with the provincial government.

“We’re trying to replace a process that has been used for close to 140 years,” Perras said of the initiatives.

Elysis belongs to a small but persistent group spread across China, Iceland, Norway, and Russia that aims to disrupt the smelting method known as the Hall–Héroult process.

Smelting involves dissolving powdery alumina in a molten salt, which is heated to over 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit. Large carbon anodes are lowered into the highly corrosive bath, and electrical currents run through the entire structure. Aluminum then deposits at the bottom as oxygen combines with carbon in the blocks, creating CO2 as a by-product. It also releases perfluorochemicals (PFCs) — long-lasting greenhouse gases — as well as harmful sulfur dioxide pollution.

The anodes themselves are made using petroleum coke, a rocklike by-product of oil refining.

The Hall–Héroult process was revolutionary, but it is extremely energy-intensive. Most of the emissions associated with producing aluminum are tied to electricity production. In the United States, more than 70% of CO2 pollution from six operating smelters came from the power supply in 2021, according to the Environmental Integrity Project. (The U.S. now has four smelters left, three of which rely on fossil-fuel power.)

Another 20% of U.S. smelters’ carbon emissions were directly from the electrochemical process, the EIP study found. Smelting was also responsible for virtually all the PFCs reported by metal producers to the Environmental Protection Agency that year.

The solution to reducing electricity-related emissions is relatively straightforward: Deploy vast amounts of wind, solar, battery storage, and other clean energy sources. But completely eliminating emissions from the smelting process requires redesigning how the anodes and cells work — and researchers are only just beginning to develop commercial-size alternatives.

Smelting represents “the hardest-to-abate emissions from primary aluminum production,” said Caroline Kim, a technical analyst on climate and energy at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “It’s really important that we’re able to replace carbon anodes,” she added, noting that PFCs last for tens of thousands of years longer in the atmosphere than CO2 does.

Elysis and other inert-anode developers have been tight-lipped about the composition and performance of their technologies, often citing trade secrets. But Elysis’ industrial-scale prototype, as well as Rio Tinto’s future demonstration plant in Quebec, could provide key answers about whether inert anodes can become the game-changing solution that many aluminum and climate experts are betting on.

“Now that it seems like [Elysis’] technology can work, the question is more about, can it be done at full-scale, sustained operating conditions at or below current costs?” Kim said.

Perras didn’t say what kinds of materials Elysis uses in its anodes. “This is our secret sauce,” he explained. But generally, the idea is to use inert metallic alloys or ceramics that don’t contain carbon, and thus won’t release CO2 and PFCs when zapped with electricity.

Elysis has also swapped the horizontal design of typical smelting pots for a “vertical approach” that Perras said looks more like a battery. These and other technical changes are expected to increase the lifespan of anodes by several years, so aluminum producers won’t have to replace them as often as they do carbon blocks, ideally reducing costs.

Aluminum experts have pointed out that the new technology could, in theory, consume more total electricity than conventional anodes, which would raise smelters’ energy needs even higher. But Perras said that Elysis is focused on making its technology competitive on both costs and energy consumption. “What we are targeting, and what we’ve seen so far, is that the technology we have is in a similar bracket of operation ranges from the incumbent Hall–Héroult technology,” he said.

Eventually, aluminum companies will be able to install Elysis’ technology in existing smelters — whenever they decide to expand production or replace old smelting pots — or in new facilities, Perras said.

In the United States, Emirates Global Aluminium is planning a $4 billion smelter in Oklahoma, while Century Aluminum is evaluating sites for a plant in the Ohio and Mississippi River Basins. Given that Elysis is aiming to mature its full-scale technology by the end of this decade, it seems unlikely that the new U.S. facilities will use inert anodes initially.

The news of Elysis’ milestone comes as the Trump administration guts federal funding for industrial decarbonization projects domestically.

Ian Wells, the federal industrial lead on climate and energy at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said the United States should be making similar investments in large-scale innovation projects to remain competitive with other countries.

Still, “we want to see emissions reductions around the world,” Wells said. If Elysis’ technology works as promised, he added, “it could be a real win for climate, and something that could help aluminum production really compete in an increasingly carbon-conscious global economy.”

President Donald Trump has made it his mission to banish offshore wind farms from America. He has derided wind energy as unreliable and expensive while freezing permitting and halting projects already under construction.

Yet a new report suggests that the president’s moves could be working against grid reliability in key parts of the country. Along the Northeast and mid-Atlantic regions, offshore wind can play a critical role in keeping the lights on year-round, especially through the winter, according to a study published this month by New York City–based consultancy Charles River Associates.

Trump’s attacks on offshore wind and other renewable sectors come amid dire challenges for the nation’s power system. The world’s wealthiest companies are building power-hungry data centers as grid infrastructure ages and households’ energy bills skyrocket. The White House itself has declared an “energy emergency,” which it’s using to push for more fossil-gas, coal, and nuclear power plants.

But offshore wind is well suited to “meeting the moment,” in part because gas plants are reliable in the summer but can buckle under winter weather, according to the study. Ocean winds in the Northeast are at their strongest and steadiest in winter months, making turbines there a way to boost the reliability of power grids connected to underperforming gas plants.

Oliver Stover, a coauthor of the study, called offshore wind farms a “near-term solution,” saying that turbines at sea and gas plants on land complement each other throughout the Northeast’s changing seasons: “They’re stronger together.”

Stover explained that if grid reliability is the goal, it makes sense for planned offshore wind farms to reach completion. Those projects will help regional grids burdened by extreme winter weather and data-center demands “buy time” as more infrastructure is built.

“Every megawatt is a good megawatt,” he said.

The periods in which offshore wind performs best also align with the time of increasing grid strain: winter mornings and evenings, when people tend to crank up the heat. While peak electricity demand has historically happened during the summer months, it is shifting to these winter moments in many parts of the country, largely due to the mass electrification of space-heating systems.

That means securing power generation during colder months must be, according to Stover, “a priority going forward.”

Stover and his colleagues aren’t the first to underscore the reliability benefits of offshore wind. Other analysts, along with grid operators, have warned that Trump’s efforts to squash certain projects that East Coast states were planning to rely on could raise blackout risks and power bills in the region.

Take Revolution Wind: Trump paused construction of the Rhode Island project in August due to “national security concerns” that a federal judge said were not rooted in “factual findings.” Having won an injunction in court, developer Ørsted eventually resumed construction one month later.

But during the pause and amid mounting uncertainty over the project’s fate, ISO New England — the region’s grid operator — released a statement saying that delaying delivery of power from Revolution Wind “will increase risks to reliability.”

Susan Muller, a senior energy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told Canary Media that if Revolution Wind were killed, the impact would be most acutely felt in winter months. That’s when the region’s limited supply of fossil gas is stretched even thinner, since the fuel is used for both building heating and power generation.

Losing Revolution Wind’s electricity entirely would have cost New England consumers about $500 million a year, according to Abe Silverman, a research scholar at Johns Hopkins University. His estimation was based on the value that the offshore project had secured in ISO New England’s forward capacity market as well as its potential to supplant costlier power plants used during grid emergencies, like snowstorms.

“We don’t need a bunch of fancy studies to tell us that these units are needed for reliability,” Silverman told Canary Media in September during Revolution Wind’s government-ordered pause.

In Virginia, the world’s data-center capital, America’s largest offshore wind farm is slated to start generating power in March 2026. Trump has not yet targeted the 2.6-gigawatt project, but if it doesn’t come online as planned, the mid-Atlantic grid region run by PJM Interconnection would be less reliable and have higher electricity costs, this month’s study says.

In a large swath of the Mid-Atlantic region, offshore wind has one of the highest “resource-adequacy” scores among energy types, according to the study. In other words, when it comes to lowering the probability of blackouts there, offshore wind outcompetes all other types of renewable energy — and is even on par with the most efficient gas-fired power plants.

But the sector is not without its issues, Stover emphasized. Even before Trump’s anti-wind policies made investors skittish and permits no longer guaranteed, construction costs had been ballooning for years, given supply chain issues and inflation.

Offshore wind farms are also, by nature, megaprojects that come with inherent logistical hurdles. Just last month, New York’s Empire Wind lost the turbine-construction vessel it was banking on, due to a skirmish between two shipbuilding companies. Only a handful of boats in the world are capable of doing that kind of work.

The report’s conclusions stand in stark contrast to rhetoric coming from top officials implementing Trump’s war on offshore wind. The sector was just taking off in the U.S. when the president was inaugurated in January, with the first commercial-scale project coming online last year and five more arrays now under construction.

“Under this administration, there is not a future for offshore wind because it is too expensive and not reliable enough,” Doug Burgum, secretary of the Interior Department, told an audience in September at a fossil-gas industry conference in Italy.

Burgum’s statements mirror some of Trump’s favorite talking points that have long misled the public about the risks of wind power. In September, Trump told the United Nations General Assembly in a speech that “windmills are so pathetic and bad” because of their unreliability, falsely claiming that wind power is “the most expensive energy ever conceived.”

The grid does not automatically face problems when “the wind doesn’t blow,” as Trump falsely claimed at the United Nations. Grid operators routinely handle the intermittent nature of power generation from multiple sources — whether it be solar, gas, or wind turbines — through grid-management techniques and, increasingly, battery storage.

Trump is wrong about costs, too.

While offshore wind energy is currently expensive, nuclear energy — a sector the Trump administration aims to boost — is typically the most expensive type of power.

Globally, power generated from wind turbines in the ocean is comparable to other sectors such as geothermal and coal when it comes to cost-competitiveness. In fact, offshore wind has become more cost-competitive relative to other power types in recent years as the sector has matured in Europe and China, according to the most recent analysis by financial advisory firm Lazard.

But when temperatures plummet, offshore wind power could be a huge cost-saver for many U.S. residents. One analysis found that in New England, if 3.5 gigawatts’ worth of under-construction offshore wind farms had been online, households there could have saved $400 million on power bills last winter. In the coming months, cost savings and reliability will take center stage as Vineyard Wind, the region’s first large-scale offshore wind farm to break ground, feeds the grid for its first full winter season.

In the waning days of the Biden administration, the Metropolitan Mayors Caucus announced an award of $14.5 million in federal funds to build almost 200 EV charging stations across the Chicago area.

A few weeks later, after President Donald Trump had taken office, the funds were “gone,” as the caucus’ environmental initiatives director, Edith Makra, put it. One of Trump’s earliest actions was to suspend the Charging and Fueling Infrastructure grant program, which is where the money for the Chicago-area charging effort had come from.

The Metropolitan Mayors Caucus is forging ahead with its EV Readiness program anyway. Even without the funds, there’s much it can do to help Chicago-area towns and cities get more chargers in the ground and EVs on the road. In fact, the caucus has already been doing that work for the last three years, thanks to funding from the Illinois utility ComEd.

Leaders say it’s an example of how local programs can make progress even when federal dollars are ripped away. It’s also a way to help meet Illinois’ ambitious goal of placing 1 million EVs on the state’s roads by 2030, a major leap from the roughly 160,000 registered as of November.

This fall, the caucus launched its fourth EV Readiness cohort, wherein representatives of 16 municipalities will learn how to upgrade their permitting and zoning processes related to EV charging, raise awareness about EVs and state and local incentives, and craft mandates for charging access.

Since 2022, 38 communities have gone through the program, and state data shows that EV registrations in most of these communities have increased faster than in the state as a whole.

Cost is one of the core factors holding back EV adoption in Illinois, and beyond.

Trump administration policies have made that hurdle even higher. Under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, rebates of $7,500 for new EVs and $4,000 for used ones expired in September, while the federal tax credit for EV chargers will disappear in June 2026.

But price is not the only factor, and as manufacturers manage to bring down costs, these other barriers will become even more crucial to address.

For example, many people hesitate to buy an electric vehicle because of range anxiety — the fear they will run out of battery and be unable to find a reliable charger. Or they may feel intimidated by the concept of an EV in general. That’s where the EV Readiness program comes in, helping municipalities increase charging stations and educate residents on EVs and the incentives that are still available.

Participating communities can achieve bronze, silver, or gold status by taking certain actions on a checklist of over 130 possible steps. These include nuanced zoning and permitting changes, like examining when chargers can be in the public right of way and processing permit applications for the equipment in 10 days or less.

Streamlining such regulations helps charging-station companies that want to do business in the area, and the owners of gas stations, apartment buildings, parking garages, corporations, and other locations who want to install ports.

Makra called EV-friendly zoning and permitting codes “a glide path for sensible development.”

“Municipalities have a big role to play in making charging infrastructure available to their communities,” added Cristina Botero, senior manager of beneficial electrification for ComEd, which funds the EV Readiness program as part of a state mandate called beneficial electrification. “This program is so effective because it’s helping the leadership of these communities understand what steps need to happen.”

The EV Readiness program also encourages municipalities to establish requirements for charging access in new construction and to train first responders to deal with EV battery fires. Participants can take steps to boost public awareness, too, informing residents about utility rate programs conducive to EV charging and creating a landing page about EVs on the town website.

“People sometimes think that the dollars are the only reason people are not transitioning to EVs,” said Botero. “But a big part of it is education.”

The EV Readiness program has so far attracted a wide range of municipalities, from the EV-friendly and relatively high-income Highland Park to smaller communities that otherwise “do not stand out from a sustainability or transportation standpoint,” noted Makra.

“What’s so gratifying is to see the diversity in jurisdictions,” she said. “They’re stepping forward and saying, ‘This would be good for our community.’”

That diversity is reflected in the new cohort, too, which includes the wealthy Chicago suburb of Winnetka and the small farm town of Sandwich.

Glen Cole, assistant manager for the city of Rolling Meadows, said the EV Readiness program helps local governments make it easier for building owners and businesses to comply with state law, which requires that all parking spaces at new large multifamily buildings and at least one space at new smaller residences have the electrical infrastructure needed to one day install an EV charger.

Rolling Meadows is a leafy suburb of about 24,000 people. Along with Chicago, it became one of three municipalities to earn gold status in the cohort that finished this summer.

Before that designation, Rolling Meadows already hosted a number of EV chargers on-site at corporate employers, including aerospace firm Northrop Grumman and the Gallagher insurance company’s global headquarters. Seven chargers are also under construction at Rolling Meadows’ city hall. The city adopted an ordinance in February mandating that new or renovated gas stations have one EV fast-charger for every four fuel pumps, and that parking lots with 30 or more spots have EV chargers.

Cole said the EV Readiness program helped advance the city’s progress

“The biggest part for us was putting in one place all these standards and expectations for an installer or investor or business, and incrementally easing into policy requirements to provide charging at public locations,” Cole said. “The availability of quick, easy, high-quality access to charging is a big determinant of whether people will take the leap to EVs, and it’s something the city can exercise a lot of control over.”

Multiple items on the EV Readiness checklist require collaborating with ComEd and making the public aware of the utility’s EV incentives and billing plans conducive to charging.

ComEd, whose northern Illinois territory is home to 90% of the state’s EVs, offers rebates for households that install “smart” Level 2 EV chargers and covers the cost of any electrical work needed. In 2026, the maximum rebate will be $2,500, and could change with market conditions, according to the utility. ComEd also covers the cost of fast chargers and the “make-ready” construction and prep work for businesses and public agencies, and offers rebates for EV fleet vehicles.

The utility has paid out over $130 million for more than 8,700 charging ports and more than 2,700 fleet vehicles since early 2024, with 80% of the funds spent in communities identified as low-income or equity-eligible, per state law prioritizing investment in underserved communities. Low-income and equity-eligible customers receive higher rebates, and Botero said the utility has done extensive outreach in those areas, where the tax-credit expiration will make it especially hard for people to afford EVs.

“The opportunities we offer are more important than ever,” Botero said.

Botero said that after the Trump administration ended EV tax credits, the utility “went back to the drawing board” and increased the rebates it had previously planned for 2026, though some of the amounts will still be lower than in 2025. Incentives for light-duty vehicles in non-equity areas will end, but the utility will increase rebates for some types of vehicles in equity areas. For example, the 2026 rebate for electric school buses in those areas will be $220,000 to $240,000, up from $180,000 this year.

The state of Illinois offers $4,000 rebates for low-income EV buyers and a $2,000 rebate for those who don’t qualify as low-income. The state also this month started accepting applications for about $20 million in grants for public charging stations. In the third quarter of 2025, Illinois logged a record number of EV sales, mirroring national trends as people scrambled to buy EVs before the tax credits expired in September.

Despite the troubling federal outlook, Botero said, “the silver lining is Illinois is extremely committed to EVs.”

Gas cars are sputtering, stuck in the slow lane — and battery-powered vehicles are gaining on them fast.

A massive shift has occurred in less than a decade. At their all-time high, in 2017, global sales of pure internal combustion vehicles hit 79.9 million units, per data from the International Energy Agency. Last year, 54.8 million internal combustion cars were sold, a 31% reduction.

Meanwhile, electric vehicles are ascendant. Nearly 11 million new EVs were sold worldwide in 2024, the vast majority in China, while consumers also bought 6.5 million plug-in hybrids — the ones with both gas engines and rechargeable batteries. Those figures represent enormous growth from just a few years ago. Back in 2017 when gas cars were at their peak, a measly 800,000 EVs and 400,000 plug-in hybrids were sold worldwide.

EVs are already more popular than fossil-fuel-guzzling vehicles in several places. And I’m not just talking about Norway. In China, the world’s largest EV manufacturer and auto sales market, around 60% of new cars sold this year will be electric. By 2030, the IEA expects that number to hit 80%.

Still, for the foreseeable future, the number of EVs on the road will pale in comparison to the number of gas-powered cars. (Older gas cars will likely be puttering around for a while even as EVs beat them out in sales.)

And the way forward is not necessarily smooth. In some countries, including the United States, the upfront costs of many EV models remain too high for consumers. Drivers are also still wary about charging infrastructure and range, even as chargers become more common. Plus, the Trump administration has eliminated U.S. policies encouraging EV adoption, causing analysts to revise down estimates of sales for what is one of the world’s largest auto markets.

But despite these speed bumps, the trend lines are tough to ignore. We’re well past peak internal combustion vehicles, and battery-powered cars are experiencing exponential growth. Eventually, that adds up to a world dominated by EVs, rather than by gas engines.

Want to claim thousands of dollars in federal tax credits for electrification upgrades that slash emissions, reduce air pollution, and enhance the comfort of your home? You have just over a month left to get them installed.

In July, Republicans in Congress voted to end two key home-energy tax credits: the Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit (25C), worth up to $2,000 for updates like an über-efficient heat pump; and the Residential Clean Energy Credit (25D), which takes 30% of the cost of rooftop solar and other clean-energy installations off your federal tax bill. To qualify for the credits, projects have to be done by Dec. 31.

Ditching our fossil-fuel equipment for electric options is an opportunity to land a punch in the climate fight. More than 40% of U.S. energy-related emissions stem from how we heat, cool, and power our homes and fuel our cars, according to the nonprofit Rewiring America. Not to mention, clean alternatives are often cheaper to run than dirty-energy versions.

Still, electrifying our lives can be hard. All-electric home upgrades are often big, complex infrastructure projects. Upfront costs can be steep.

But appliances, like cars, come in a wide range of models with different features and a diversity of price points.

It’s worth spending some time to think through the options — after all, doing so could save you tens of thousands of dollars by avoiding an unnecessary electrical-service upgrade or an overpowered heat pump. But to lock in the federal discounts, you’ll need to get up to speed quickly.

That’s where Canary Media can help. I’ve pulled the most relevant stories from the archives to get you prepped on your home retrofit. Dive in anywhere you like.

Why electrify?

Prep Work

How to Electrify Your Home

Get a Heat-Pump Water Heater

Electrify Your Cooking

Get a Heat-Pump Clother Dryer

Get a Charger for Your EV

Electrify Your Landscape Maintenance

Bank Energy With Home Batteries

Need Inspiration?

Coaching & Tools

The Shortcut

Here’s a last piece of advice to help you fast-track electrification projects so that you can get those federal tax credits. Journalist Justin Gerdes, who writes the wonderfully researched newsletter Quitting Carbon, says this is his No. 1 pointer for anyone planning an all-electric home retrofit:

“Search for a specialist electrification contractor you can trust.”

To make that process easier, Rewiring America and the BetterHVAC Alliance launched the National Quality Contractor Network in September. The associated directory is full of certified installers who know and love heat pumps, heat-pump water heaters, insulation, EV chargers, and more.

Gerdes’ advice is golden in a world with or without federal tax breaks. The U.S. government continues to fund state-run home energy rebates for lower-income households. And you can still find a bonanza of state, local, and utility incentives to break up with fossil fuels.

It’s also still early in the adoption curve for many of these electrified technologies. As they become more commonplace, we could see prices drop.

So while now is a great time to invest in electric appliances and reap the benefits of a clean-energy dream home, 2026 — and the years to come — will be too.