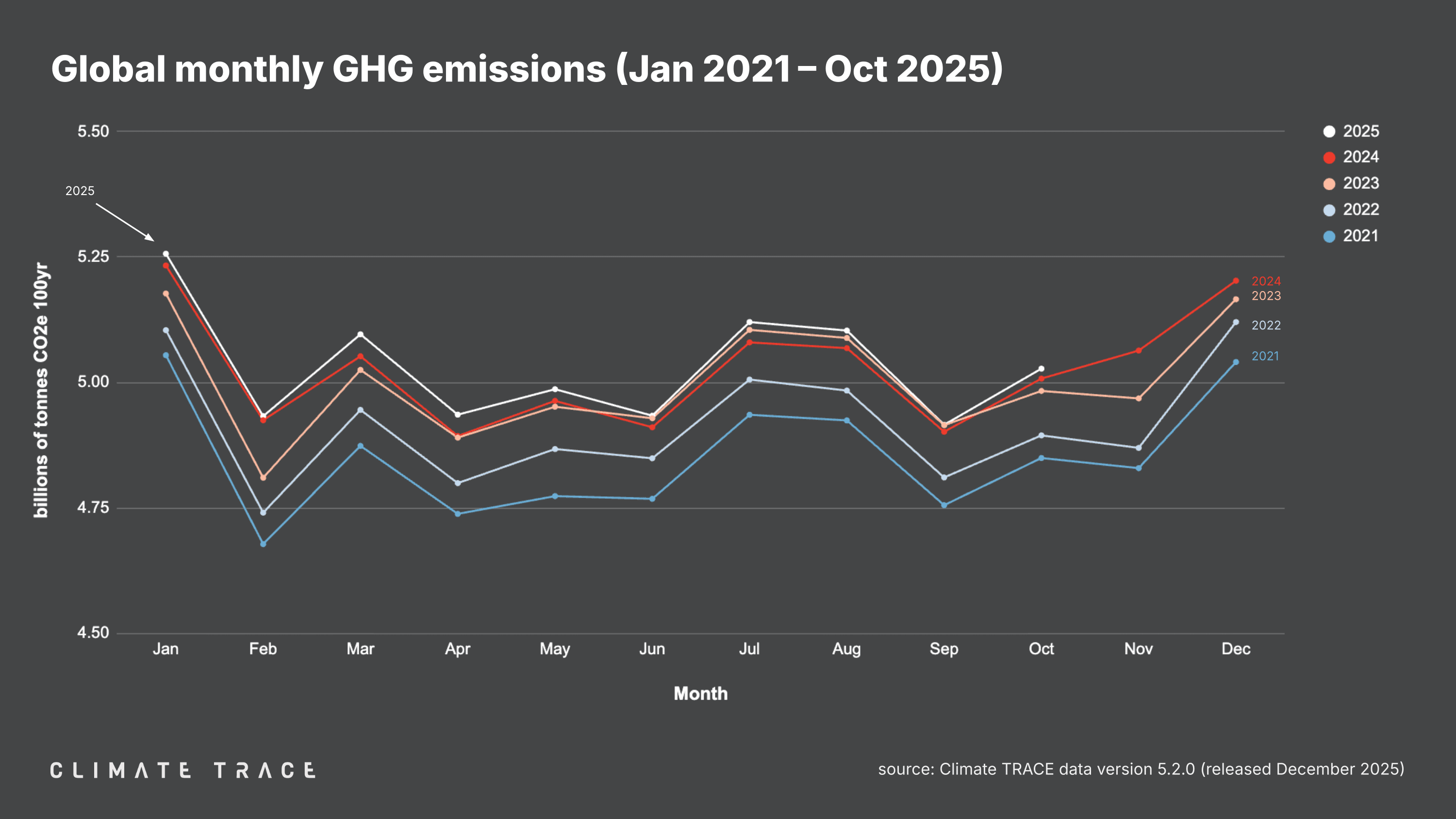

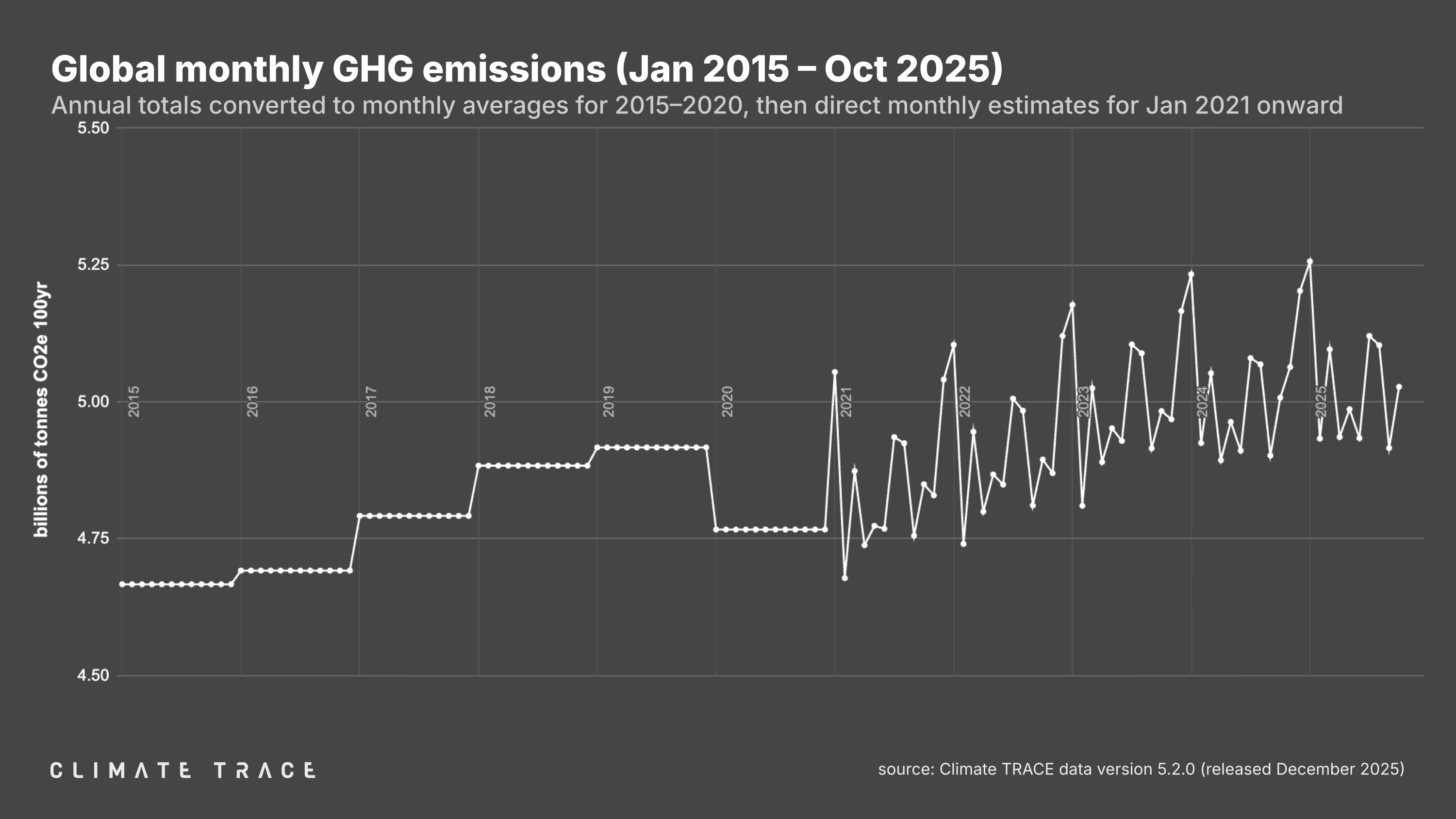

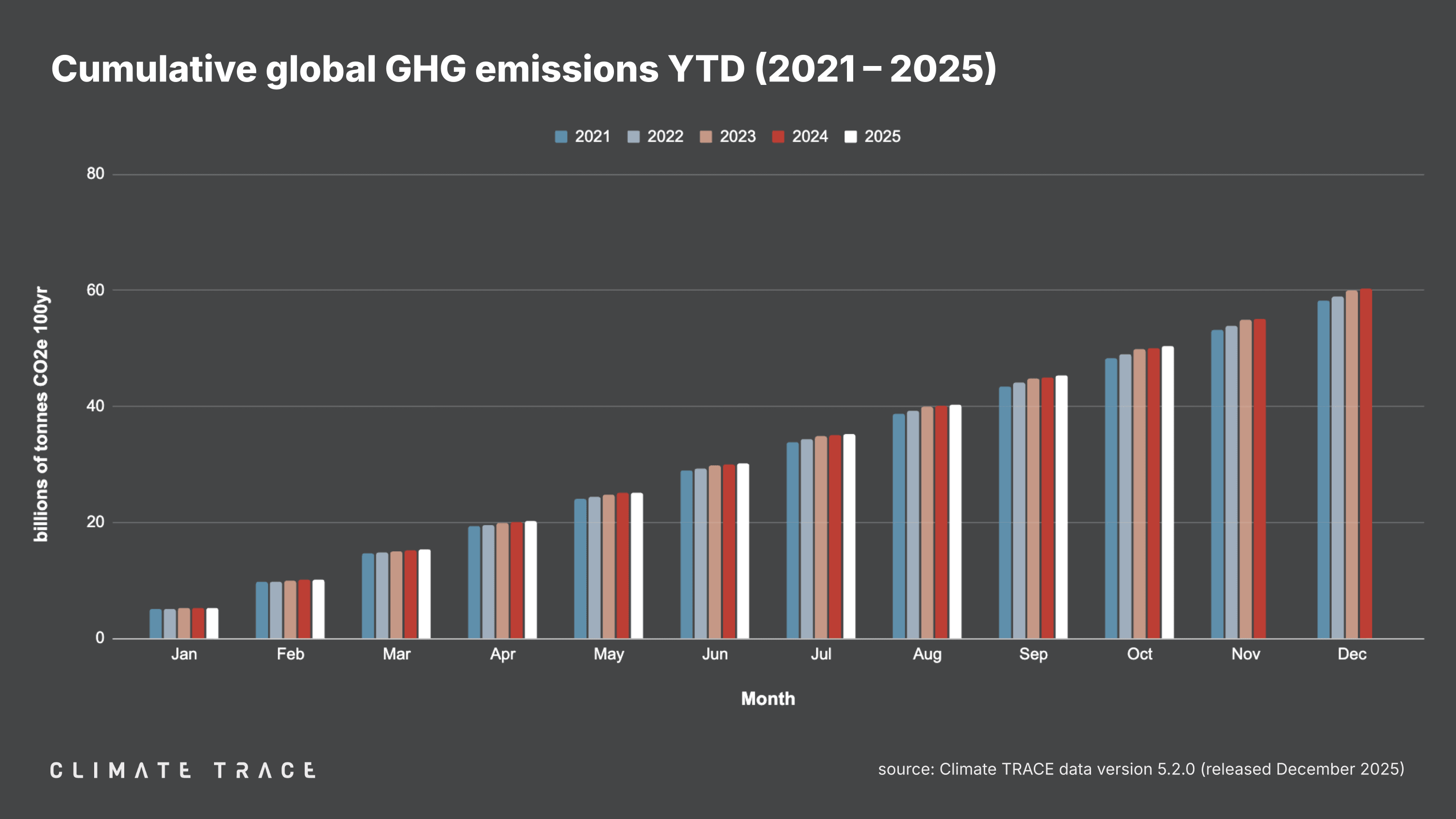

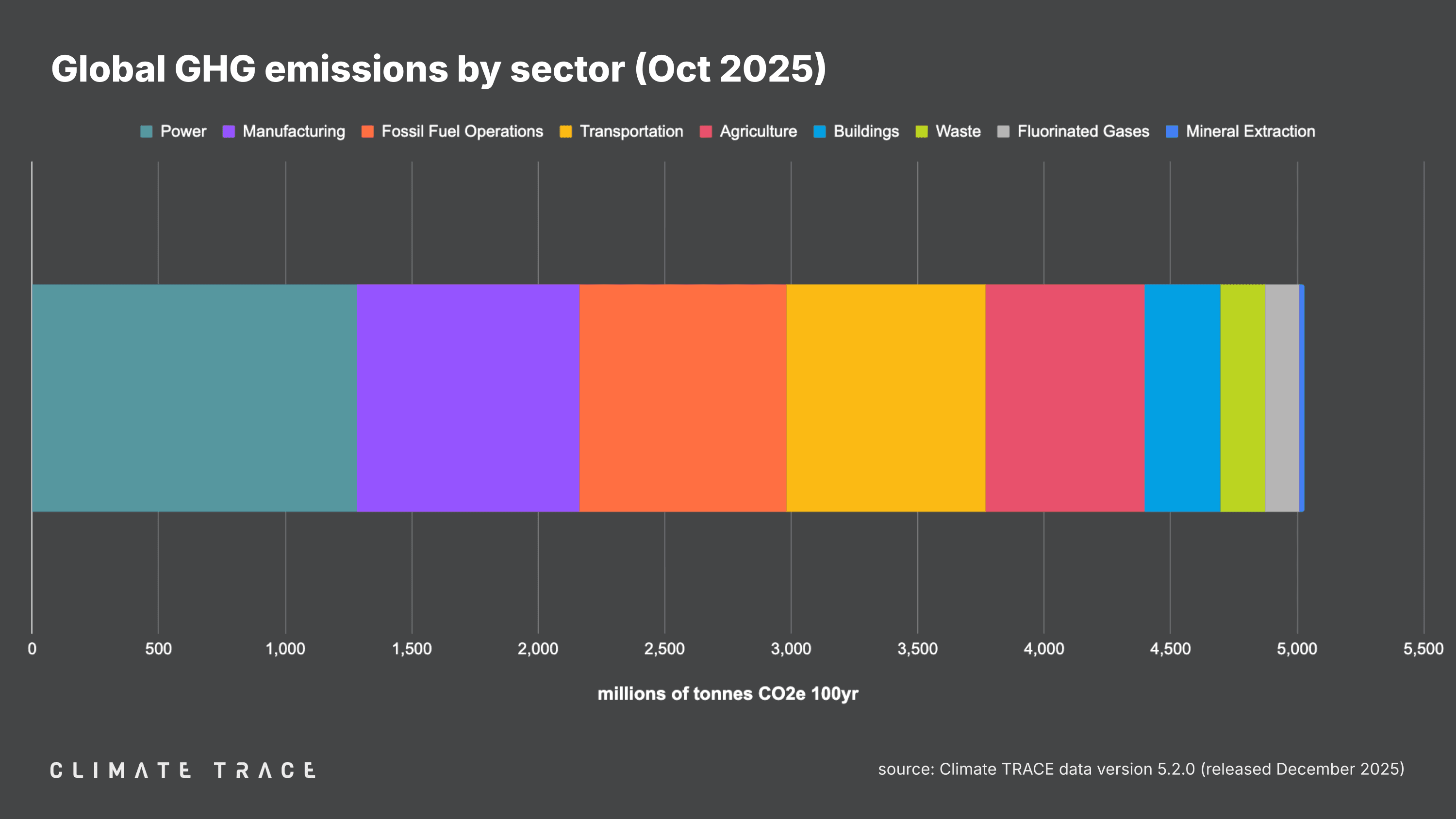

December 18, 2025 – Today, Climate TRACE reported that global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for the month of October 2025 totaled 5.03 billion tonnes CO₂e. This represents an increase of 0.40% vs. October 2024. Total global year-to-date emissions are 50.31 billion tonnes CO₂e. This is 0.55% higher than 2024's year-to-date total. Global methane emissions in October 2025 were 33.83 million tonnes CH₄, an increase of 0.07% vs. October 2024.

Data tables summarizing GHG and primary particulate matter (PM2.5) emissions totals by sector and country, and GHG emissions for the top 100 urban areas for October 2025 are available for download here.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Country: October 2025

Climate TRACE's preliminary estimate of October 2025 emissions in China, the world's top emitting country, is 1.42 billion tonnes CO₂e, an increase of 8.46 million tonnes of CO₂e, or 0.60% vs. October 2024.

Of the other top five emitting countries:

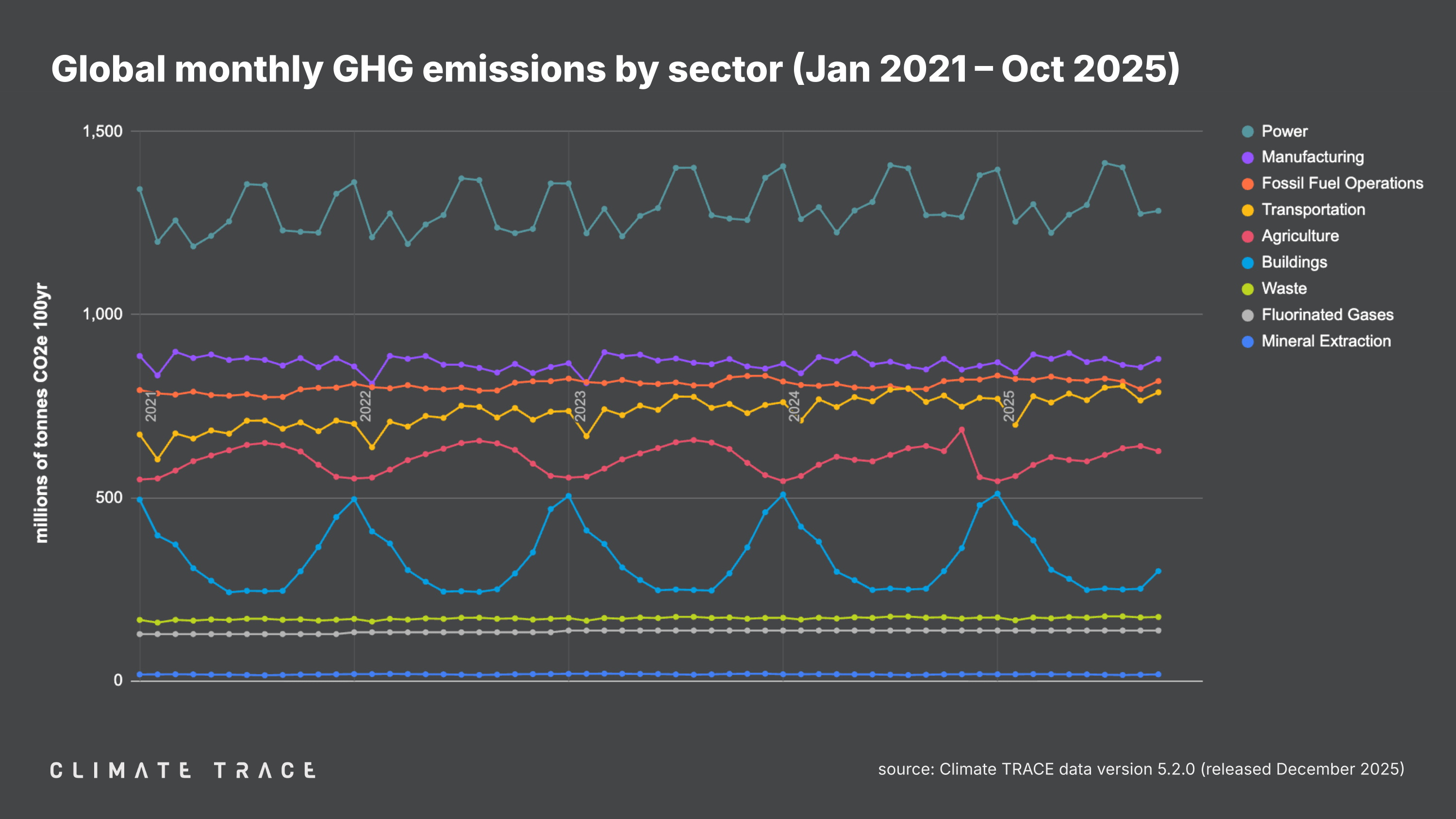

Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector: October 2025

Greenhouse gas emissions increased in October 2025 vs. October 2024 in power, transportation, and waste, and did not decrease in any major sectors. Transportation saw the greatest change in emissions year over year, with emissions increasing by 1.13% as compared to October 2024.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions by City: October 2025

The urban areas with the highest total GHG emissions in October 2025 were Shanghai, China; Tokyo, Japan; Houston, United States; New York, United States; and Los Angeles, United States.

The urban areas with the greatest increases in absolute emissions in October 2025 as compared to October 2024 were Ramagundam, India; Obra, India; Newcastle, Australia; Toranagallu, India; and Owensboro, United States. Those with the largest absolute emissions declines between this October and last October were Waidhan, India; Korba, India; Anpara, India; Rotterdam [The Hague], Netherlands; and UNNAMED, India.

The urban areas with the greatest increases in emissions as a percentage of their total emissions were Butibori, India; Uruguaiana, Brazil; Shitang, China; Obra, India; and Shostka, Ukraine. Those with the greatest decreases by percentage were Heilbronn, Germany; UNNAMED, India; Santaldih, India; Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Russia; and Alotau, Papua New Guinea.

RELEASE NOTES

Revisions to existing Climate TRACE data are common and expected. They allow us to take the most up-to-date and accurate information into account. As new information becomes available, Climate TRACE will update its emissions totals (potentially including historical estimates) to reflect new data inputs, methodologies, and revisions.

With the addition of October 2025 data, the Climate TRACE database is now updated to version V5.2.0. This release expands asset coverage to include 245 additional power plants (globally) and 2,287 additional cattle operations (all in Japan). It includes non-greenhouse gas emissions for petrochemical steam cracking facilities in Asia Pacific and the Middle East. The waste sector has updated modeling for its landfill emissions: emissions are now modeled natively for each month, where previously, annual estimates were disaggregated into monthly estimates. The release also includes data fixes within transportation and waste sectors.

A detailed description of data updates is available in our changelog here.

To learn more about what is included in our monthly data releases and for frequently asked questions, click here.

All methodologies for Climate TRACE data estimates are available to view and download here.

For any further technical questions about data updates, please contact: coalition@ClimateTRACE.org.

To sign up for monthly updates from Climate TRACE, click here.

Emissions data for November 2025 are scheduled for release on January 29, 2026.

About Climate TRACE

The Climate TRACE coalition was formed by a group of AI specialists, data scientists, researchers, and nongovernmental organizations. Current members include Carbon Yield; Carnegie Mellon University's CREATE Lab; CTrees; Duke University's Nicholas Institute for Energy, Environment & Sustainability; Earth Genome; Former Vice President Al Gore; Global Energy Monitor; Global Fishing Watch/emLab; Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab; OceanMind; RMI; TransitionZero; and WattTime. Climate TRACE is also supported by more than 100 other contributing organizations and researchers, including key data and analysis contributors: Arboretica, Michigan State University, Ode Partners, Open Supply Hub, Saint Louis University's Remote Sensing Lab, and University of Malaysia Terengganu. For more information about the coalition and a list of contributors, click here.

Media Contacts

Fae Jencks and Nikki Arnone for Climate TRACE media@climatetrace.org

This analysis and news roundup come from the Canary Media Weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it every Friday.

President Donald Trump’s sweeping freeze on offshore wind construction is starting to hurt his own party’s energy ambitions.

Just days before Christmas, the Trump administration halted work on all five large-scale offshore wind farms under construction in the U.S, citing unspecified national security concerns. The order may have come as a shock to the project developers, who received letters from the Interior Department only after Fox News publicly reported on the move, as Canary Media’s Clare Fieseler reported at the time.

All but one of the targeted developers have since sued the Trump administration. Danish developer Ørsted filed two separate suits over pauses to its nearly complete Revolution Wind — which the Interior already halted for a month last fall — and to Sunrise Wind. In another lawsuit, Equinor warned that the freeze would result in the “likely termination” of its Empire Wind project off New York, which also suffered a monthlong stop-work order last spring. And Dominion Energy is asking a judge to let construction resume on the utility’s Virginia project, once considered safe because it had the backing of the state’s outgoing Republican governor.

The halts are also sparking backlash on Capitol Hill that could derail some of the White House’s other energy plans. In the weeks leading up to the holidays, Congress had taken up what seemed like the millionth round of negotiations to reform energy-project permitting. Reforms are essential to Republicans’ goal of speeding fossil-fuel construction, and this time around, they’d actually made progress with the House’s passage of the SPEED Act, which had support from a handful of Democrats.

That bill requires 60 votes to clear the Senate, but with Republicans holding just 53 seats, it would need significant Democratic support. That won’t happen while the Interior’s stop-work order remains in place, two high-ranking Senate Democrats say.

“The illegal attacks on fully permitted renewable energy projects must be reversed if there is to be any chance that permitting talks resume,” Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) and Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.) said in a late December statement calling out the offshore wind halts. “There is no path to permitting reform if this administration refuses to follow the law.”

Congress reconvened this week, but Whitehouse affirmed that permitting talks won’t go anywhere until offshore wind construction is free to proceed.

Venezuela is dominating the energy discussion

While the Trump administration used allegations of narcoterrorism to justify its invasion of Venezuela and seizure of leader Nicolás Maduro, pretty much every conversation since has revolved around the country’s oil resources. In his first news conference after Maduro’s capture, President Donald Trump said the U.S. would “run” Venezuela and control its oil production, and he has been pressuring American oil companies to reinvest in the South American nation.

But it’s not just oil that the White House is eyeing. An administration official told Latitude Media that Trump and the private sector may also target Venezuela’s critical mineral resources, though experts warn that little reliable data exists on those deposits and that the country’s mining sectors are in disarray.

More delayed coal-plant retirements

The U.S Department of Energy issued a wave of orders in the waning days of 2025 to keep coal power plants running past their retirement dates. The first targeted a plant in Centralia, Washington, which its owner had been planning to close since 2011. Next up came orders to keep two Indiana coal plants open until at least late March. And just before year’s end came another, this one targeting Unit 1 at Colorado’s Craig power plant.

Both the Craig facility and one of the units in Indiana have been out of commission due to mechanical failures since earlier in 2025, meaning their owners will now have to shoulder potentially huge repair costs to comply with the federal mandate, Canary Media’s Jeff St. John reports.

And the U.S. EPA may soon throw another lifeline to coal power. The agency plans to let 11 plants dump toxic coal ash into unlined pits years after current federal rules allow, Canary Media’s Kari Lydersen reports. Without the extension, those plants would likely shutter.

A just transition? As the European Union shifts off coal, advocates and leaders are working to ensure Poland’s powerhouse mining region isn’t left behind. (Canary Media)

It’s electrifying: The rising cost of natural gas and growing popularity of heat pumps and induction cooking indicate a bright future ahead for building electrification in the U.S. (Canary Media)

State of the emergency: In the year since Trump declared a national emergency on energy, experts say an actual electricity-supply crisis has emerged, and the White House is discouraging renewable energy development that could help solve it. (Canary Media)

A new EV champion: Tesla’s sales fell year-over-year in 2025, finishing at 1.64 million deliveries, putting the company’s sales totals behind emerging Chinese company BYD, which sold 2.26 million EVs. (AFP)

Back from the dead: Nearly obsolete fossil-fuel-fired peaker plants are being forced back into service thanks to rising electricity demand from AI data centers. (Reuters)

Solar’s bigger in Texas: Data shows that solar arrays provided more power to Texas’ standalone grid in 2025 than did coal-fired power plants, marking the first time that has happened. (Houston Chronicle)

The Environmental Protection Agency plans to let 11 coal plants dump toxic coal ash into unlined pits until 2031 — a full decade later than allowed under current federal rules.

The move tosses a lifeline to the polluting power plants. If the facilities were barred from dumping ash into unlined pits, they would be forced to close, since they can’t operate if they don’t have a place to dispose of the ash, and the companies say finding alternative locations for disposal would be impossible.

These 11 plants have already circumvented the 2021 deadline to close such pits, through a 2020 extension offer from the first Trump administration. By filing applications for that extension through 2028, the plants were allowed to keep running even though the EPA has yet to rule on the applications.

On January 6, the EPA held a virtual public hearing on its proposal to give the plants an additional three years to stop dumping coal ash in unlined pits. Attorneys, advocates, and people who live near the plants called the plan illegal, a threat to public health, and another tactic by the Trump administration to prolong the lives of polluting coal plants.

In recent months, the Department of Energy has ordered coal plants scheduled for retirement to continue operating, saying their electricity is needed — an argument the EPA echoed in its proposal. Some state regulators, grid operators, and energy experts have pushed back on the notion that it is necessary to force these power plants to stay online. At the hearing, critics of the EPA’s proposed extension said reliability concerns are outside the agency’s coal ash mandate to protect human health and the environment.

“If the proposal is not finalized, the plants would have to close their [coal ash] impoundments and cease burning coal by 2028,” said Lisa Evans, a senior attorney for the environmental law firm Earthjustice. But under the proposed extension, “the plants will continue to burn coal, thus creating additional air pollution,” and contamination from coal ash.

Coal ash dumped in unlined pits can leach into groundwater, potentially contaminating drinking water wells with carcinogens and other dangerous elements. In 2018, the federal D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the 2015 federal regulation on Coal Combustion Residuals (CCR) must be strengthened to better deal with such sites. The ruling led to an April 2021 deadline to start closing unlined coal ash ponds.

Through a 2020 extension offer from the first Trump administration, the EPA invited power companies to apply for the extension through 2028 if they had no other way to deal with the ash and were otherwise in compliance with the rules for disposal.

The EPA made a final decision in only one case, denying an extension to the troubled James M. Gavin plant in Ohio in 2022. But any company that filed an application has been able to keep its plant running while the EPA considers the case, something critics say is an obvious loophole.

The latest proposal would let three such plants in Illinois, two in Louisiana, two in Texas, and one each in Indiana, Ohio, Utah, and Wyoming operate until 2031.

“That [2021] deadline was established to stop ongoing contamination and protect communities,” said Cate Caldwell, senior policy manager of the Illinois Environmental Council, which represents 130 groups in the state. “By expanding a loophole created during the first Trump administration, EPA would allow coal plants to delay closure for at least three more years and potentially much longer.”

The EPA’s previous and proposed regulations say that an extension for unlined pits can be granted only if the site is in compliance with the federal coal ash rules, including those involving cleaning up groundwater contamination.

At the hearing, experts argued that the 11 plants are not in compliance. Groundwater monitoring data that the companies are required to provide shows that all the sites eligible for the extension have elevated levels of contaminants linked to coal ash.

“EPA never reviewed these demonstrations,” Evans said. “If they did, I am confident that they would likely find that each of the plants are ineligible for an extension.”

In the virtual hearing, Indra Frank, coal ash adviser to the citizens group Hoosier Environmental Council, told the EPA that the R.M. Schahfer plant in Indiana is violating the coal ash rules by failing to file the required groundwater monitoring reports and other documents for a retired coal ash pond, which she and Earthjustice attorneys discovered in reviewing maps and images of the site.

“That impoundment is subject to the federal CCR rule, but it has not met any of the requirements of the rule. To qualify for the extension offered in 2020, utilities were required to be in full compliance,” Frank said at the hearing. “Since Schahfer was not in compliance, Schahfer did not qualify for the extension in 2020 and should not receive the additional proposed extension.”

Schahfer’s two coal-fired units were scheduled to close in December, but the Department of Energy ordered the plant to keep running — though one unit has actually been offline since July in need of repairs. In an August email to the EPA, an official with the plant’s parent company said the coal ash extension would be necessary to justify spending money to get the plant back online.

Locals are dismayed that Schahfer may continue to run and say that no more coal ash should be placed in its unlined pond. Arsenic, molybdenum, cobalt, and radium have been found in groundwater near the pond, and the coal ash is held back by a dam with a high hazard rating, meaning its failure would be likely to cause death.

“We just see this proposed rule as a downright unlawful, reckless attempt by the Trump EPA to let polluters keep polluting,” said Ashley Williams, executive director of the advocacy organization Just Transition Northwest Indiana. She called the coal ash at the Schahfer site a “largely silent crisis that we’ve had to continue to sound the alarms on.”

Colette Morrow, a professor at an Indiana public university, told the EPA during the hearing that she suffers from an autoimmune disease and fears for her health if the Schahfer plant is allowed to keep running.

“This is unconscionable that the U.S government would put its own people at risk to such a high degree, only in order to enhance profits of these utility providers,” Morrow said.

Retired chemistry teacher Mary Ellen DeClue said she was shocked to learn about the contaminants that could be leaching into Illinoisans’ drinking water — since many rural residents tap private wells.

“This is not acceptable,” she said, imploring the EPA not to “rubber-stamp” the extension.

The three Illinois plants seeking the extension — Kincaid, Newton, and Baldwin — are owned by Texas-based Vistra Corp. The plants have already benefited from leniency under the Trump administration: Last year the company accepted the administration’s offer of an extension on complying with federal air pollutant limits.

Illinois is one of the states with the highest number of coal ash sites, according to data filed by power companies. Illinois coal plants will have to shut down by 2030 under state law, but each extra year of operation places residents at risk, local advocates say.

“Many of these communities rely on groundwater for drinking water and lack the resources to address widespread contamination on their own,” Caldwell of the Illinois Environmental Council told the EPA. “The agency should not be asking coal companies how long they would like to continue dumping toxic waste. It should be enforcing closure requirements that are already long overdue.”

2025 was, to put it very mildly, an eventful year for the U.S. power sector. The rise of data centers drove soaring electricity demand, debates about energy affordability hit a fever pitch, and the Trump administration went to unprecedented — and legally dubious — lengths to prop up coal and stymie renewables.

Yet despite the excitement, the broader electricity mix looked about the same as ever. Natural gas provided by far the biggest share of the country’s electricity, followed by nuclear, followed by coal, per U.S. Energy Information Administration data released in December.

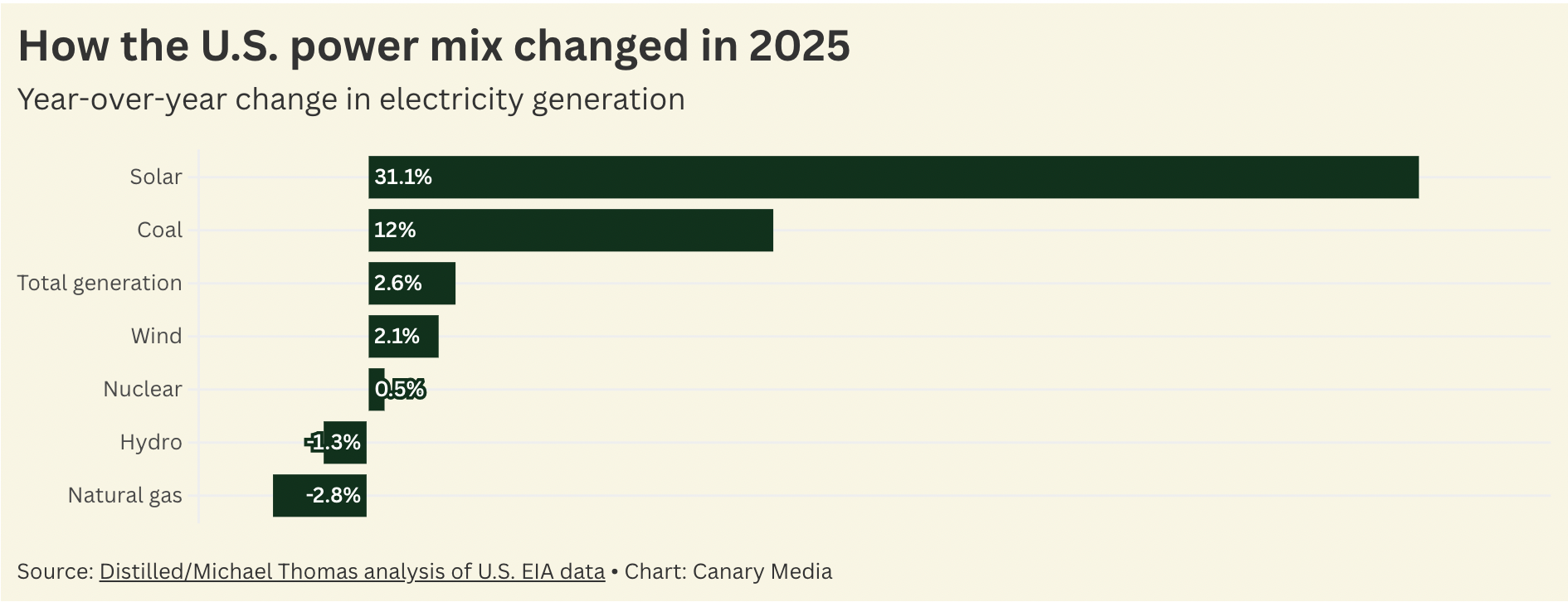

The story gets more interesting, however, when you zoom in. Last year, solar panels produced 31.1% more electricity than in 2024, while coal-fired power plants generated 12% more megawatt-hours, according to EIA data crunched by Michael Thomas at Distilled. Natural gas generation, meanwhile, fell by nearly 3%.

Overall, power demand ticked up by 2.6% — a seismic number for a sector that has been stagnant for over a decade.

Solar’s growth is easy enough to explain: We need more power, and no source of electricity is quicker or cheaper to deploy. The rise of cost-effective battery storage has made solar even more attractive. In fact, despite the considerable roadblocks created by the Trump administration last year, solar and batteries together accounted for more than 80% of new energy capacity added to the grid between last January and November.

The dynamics around coal and gas are a bit wonkier.

Yes, as Thomas points out, President Donald Trump made a show of celebrating “beautiful, clean coal” last year. His administration also used emergency powers to order a number of aging, expensive-to-run coal plants to stay open on the eve of their planned closures. But it’s not as if Trump isn’t also supportive of the U.S.’s natural gas industry. So why the rise for one and the fall for the other?

It boils down to market forces. Gas prices spiked last year, and so did electricity demand. That bolstered the financials for some coal plants, resulting in more coal generation — and, as Thomas points out, a dirtier grid. Power-sector emissions jumped by 4.4% from 2024 to 2025, per Thomas, a significant leap and the second year in a row of rising emissions after years of consistent declines. The EIA expects coal-fired power to shrink this year, however, as more renewables come online and once again erode the economic case for burning the dirty fuel.

And despite coal’s brief resurgence, it wasn’t all positive for the fossil fuel in 2025. In fact, a separate metric may be a better indicator of its long-term outlook: For the second year in a row, wind and solar together produced more U.S. electricity than did coal.

The Trump administration’s campaign to force aging coal plants to keep running has entered a new phase: ordering broken-down units to come back online. Repairing those polluting plants could take months and cost tens of millions of dollars — all just to comply with legally questionable stay-open mandates that last only 90 days at a time.

In December, the Department of Energy ordered four coal plants — two in Indiana and one each in Colorado and Washington state — that were set to retire by year’s end to continue generating power for 90 days. Two of them have units that have been out of commission because of mechanical failure: Colorado’s Craig Generating Station Unit 1 has been down for three weeks and Indiana’s R.M. Schahfer Unit 18 has sat idle since July.

This means the utilities that own those plants must now race to bring them into working order, even though they’ve long ago deemed the facilities uneconomical to operate. Customers already grappling with skyrocketing electricity rates are likely to shoulder the costs of fixing and running the equipment. Complicating matters further is that the required repairs may not even be feasible to complete within the 90-day window covered by the DOE orders.

“Coal plants — and in particular the plants DOE has targeted — are these clunky old jalopies that, out of nowhere, just fail,” said Michael Lenoff, a senior attorney at nonprofit law firm Earthjustice, one of several environmental groups challenging the must-run orders. “DOE forcing these things to be available, and in some instances to run, actually creates reliability risk to the grid.”

The Trump administration claims that keeping the plants online is the only way to prevent blackouts in the near future. Last month’s must-run orders, as well as earlier ones forcing a Michigan coal plant and an oil- and gas-fired plant in Pennsylvania to stay open, were issued under Section 202(c) of the Federal Power Act, which lets the DOE compel power plants to operate to forestall immediate energy emergencies.

Critics say the Trump administration has weaponized this authority to prop up the U.S. coal industry, which provided about half the country’s generation capacity in 2001 but now supplies about 15%. None of the plants that the DOE has forced to stay open is needed for near-term reliability, according to the utilities, state regulators, and regional authorities responsible for maintaining a functioning grid. And despite its claims of an energy crisis, the federal government is throwing up roadblocks to wind, solar, and battery projects that are a fast and cheap way to add electrons to the grid.

The costs of the Trump administration’s coal interventions are mounting. The Sierra Club estimates that the price tag of keeping those six power plants running under the DOE’s orders has added up to more than $158 million as of this week.

And utilities that have to repair units before starting to generate power again will face a new set of costs.

In Indiana, Schahfer’s Unit 18 has been offline since July because of a damaged turbine. Vincent Parisi, president of Northern Indiana Power Service Co., the utility that owns and operates the plant, told Indiana state regulators in December, “It can take six months or longer for us to ultimately be able to get that unit back to where it would need to be to operate for an extended period of time.” Parisi did not provide cost estimates for those repairs or for extending operations at the Schahfer plant, and a NIPSCO spokesperson declined to provide an estimate to Canary Media.

In Colorado, Craig Unit 1 has been offline since Dec. 19 because of mechanical failure, according to Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association, the electric cooperative that operates and holds a partial ownership stake in the plant. “As a not-for-profit cooperative, our membership will bear the costs of compliance with this order unless we can identify a method to share costs with those in the region,” Tri-State CEO Duane Highley said in a December press release. “There is not a clear path for doing so, but we will continue to evaluate our options.”

Tri-State spokesperson Mark Stutz said the co-op and its partners don’t have firm cost estimates for repairs or for compliance with the order, “which will likely require additional investments in operations, maintenance, and potentially fuel supply.”

Consultancy Grid Strategies has estimated that keeping Craig 1 running for 90 days would cost at least $20 million, and that running it for a year could add up to $85 million to $150 million. Those costs do not include repairs of the equipment that failed and caused it to go offline.

Fixing up coal plants to comply with the DOE mandates could also put utilities in a legal bind. State attorneys general and environmental groups are already challenging many of the agency’s Section 202(c) orders, saying those orders are based on false premises and violate the law’s strictures for the agency to use its authority only to prevent immediate grid emergencies.

These arguments may soon see their day in federal court. In December, a coalition of environmental groups, including Earthjustice, filed a legal brief with the federal D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals challenging the DOE’s use of Section 202(c) authority to force the J.H. Campbell coal plant in Michigan to keep running. The brief asks the court to “put an end to the Department’s continued abuse of its authority, which has imposed millions of dollars in unnecessary costs and pollution on residents of Michigan and the Midwest.”

Nor does the DOE have authority to order utilities to undertake repairs or alterations to power plants under Section 202(c), Earthjustice, Sierra Club, and Indiana-based environmental and consumer advocates argued in a December letter to NIPSCO. The groups warned the utility that they plan to legally challenge any repair costs it tries to pass on to customers.

“The authority does not exist within Section 202(c) for DOE to force upgrades or major investments in energy-generating facilities. The authority only extends to operational choices,” said Greg Wannier, senior attorney for the Sierra Club. “I do think that at some point, regulated utilities do bear some responsibility for not taking illegal actions to comply with illegal orders.”

NIPSCO spokesperson Joshauna Nash told Canary Media that compliance with the DOE’s order is “mandatory.” The utility is “carefully reviewing the details of this order to assess its impact on our employees, customers, and company to ensure compliance,” Nash said. “While this development alters the timeline for decommissioning this station, our long-term plan to transition to a more sustainable energy future remains unchanged.”

The Trump administration seems set to continue using Section 202(c) authority. The DOE has issued three consecutive 90-day must-run orders for both the J.H. Campbell plant and the Eddystone plant in Pennsylvania. It has also issued a report that appears to lay the groundwork for justifying federal action to prevent any fossil-fueled plant from closing, citing data that critics say has been cherry-picked and misrepresented to paint a false picture of a power grid on the verge of collapse.

If the DOE continues to prevent fossil-fuel plants from closing, the costs could reach into the billions of dollars. Grid Strategies has estimated that forcing the continued operations of the nearly 35 gigawatts’ worth of large fossil-fueled power plants scheduled to retire between now and the end of 2028 could add up to $4.8 billion over that period.

Financial concerns aside, forcing utilities to react to successive 90-day emergency orders amounts to “sticking a wrench in the spokes of how utilities and their state regulators have planned their systems,” said Brendan Pierpont, director of electricity at think tank Energy Innovation.

The utilities under DOE must-run orders have developed plans to retire workers at those plants or move them to other jobs, he said. They’ve ended long-term coal-delivery contracts and procured alternative resources to make up for the lost power from the shuttering units. Some plan to convert the facilities to run on fossil gas, as is the case with the Schahfer plant and the coal plant in Washington state. Those projects will likely be delayed if the coal units must keep running, he said.

Earthjustice’s Lenoff agreed that the DOE’s intrusion into those plans is “creating uncertainty that harms investment, raises costs, and disrupts orderly planning by experts and authorities who know what they’re doing. The Department of Energy has shown that it is just blundering into markets and processes that it doesn’t understand with flimsy arguments that don’t withstand scrutiny. And other people are bearing the costs.”

BYTOM, Poland — Adam Drobniak pulled into the parking lot of a convenience store and stepped out of his sedan into the overcast afternoon. A coal mine just across the street cast dust into the air as conveyor belts sorted the shards of black, burnable rock. Down the road, a goliath coking plant belched fire and thick clouds of steam as its roaring ovens cooked off impurities in the coal to refine it for blast furnaces. The air smelled burnt, and it was difficult to tell whether the sky was gray from clouds or smoke. Drobniak took out a silver case from his pocket and flashed a mischievous smile as he withdrew a hand-rolled cigarette, then dangled it from his lips and touched the flame of an old-fashioned Zippo to the tip.

“I spent decades around this,” he said, motioning to the surrounding area. “How much more damage can it do?”

Bytom is located in Silesia, an ethnically distinct province in southern Poland and the European Union’s biggest coal-mining region. Silesia still produces millions of tons of coal annually and has been extracting it from the ground for hundreds of years. The first state-owned coal mine opened about 20 minutes southwest of Bytom in 1791, when the region was controlled by Prussia. Over the next two centuries, the area was transformed into a key node in Central Europe’s industrial supply chain, with the third-largest gross domestic product of any province in the region, behind only the Polish capital of Warsaw and the Romanian capital of Bucharest. Coal became a way of life.

Now Silesia is figuring out the least painful way to kill the coal industry.

An economist by training, Drobniak has become something of a doctor administering palliative care.

Over the past five years, Drobniak, who works at Poland’s University of Economics in Katowice, Silesia’s provincial capital, has partnered with labor unions, local officials, and industry leaders on a “just transition” plan to shift Silesia away from coal without abruptly destroying the livelihoods of thousands of people whose families have worked in the industry for generations, spanning kingdoms, republics, communism, and capitalism.

That plan, which seeks to capitalize on an economic transition already underway in Poland and give workers the time and resources to adjust, has become something of a model for neighboring countries such as Romania and Bulgaria, which are struggling with their own transition away from coal. And, though the plan faces pushback from EU policymakers in Brussels and shifting priorities in Warsaw as different parties vie for national power, Poland seems to be moving in the right direction. Across the province, new industries — from manufacturing to technology — are booming.

However, development has not been evenly distributed. The economic gap between cities such as Bytom and Katowice has more than doubled in the past three decades. While Katowice teems with new buildings and businesses, Bytom represents what Drobniak called the “worst case” for the transition, a corner of Silesia unusually entrenched in coal and suffering from high poverty and unemployment rates as the industry shrinks. The city has lost nearly a quarter of its population since the early 2000s, with residents leaving in pursuit of better opportunities elsewhere. Indeed, the coal mine that was cranking away when Drobniak and I visited Bytom this fall was set to close in December. Most of the miners there will likely transfer to other coal mines in Silesia.

As in many parts of Europe, wind turbines line the horizon on the drive into Silesia. Solar panels glimmer on old stone roofs. Poland is racing to build its first nuclear power plant and is inking deals with virtually every major small-modular-reactor vendor in the U.S. and the United Kingdom. The country is even carrying out drilling experiments to see whether geothermal heat could replace coal in its district heating system. It’s no wonder why: Poland’s coal phaseout is set to kick up a notch this year, even as electricity demand is rising. But the size, history, and Europe-wide importance of Silesia’s coal industry put the phaseout on a different scale — making the steps the region is taking to avoid upheaval for workers especially consequential.

The Silesian coal industry’s first brush with death came three decades ago.

In 1996, Poland enacted sector-wide reforms meant to consolidate mines and privatize state-owned enterprises as the country transformed after the fall of the Soviet Union. Over the course of just a few years, the number of jobs in the mining sector plunged by 356,000. After Poland joined the EU in 2004, its economy grew rapidly and employment in the coal sector partially recovered. But it dipped again, by tens of thousands of jobs, during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic.

Poland’s overall wealth expanded as the country integrated into the EU. But the relationship also brought tensions. As Brussels imposed increasingly strict targets to cut emissions from power plants and phase out coal, many countries built up renewables backed by natural-gas-fired plants. Pipelines stretching westward across Europe from the bloc’s eastern border soon flowed with gas molecules from Russia, one of the world’s biggest producers.

Poland was reluctant to follow suit. Centuries of fighting off invasions from the east — including four decades under Moscow’s control as a Soviet satellite — left Poles wary of depending on Russia for fuel. When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022 and started throttling Europe’s gas supply, Warsaw’s continued reliance on coal seemed, to some extent, vindicated. However, even as the conflict underscored the risks of Russian gas, surging electricity demand across the EU and looming emissions-cutting deadlines only emphasized the need for Poland to find new sources of power.

To Silesia’s coal miners, the end is looking inevitable.

“We are fighting for our lives here,” Krzysztof Stanisławski, a lifelong miner, told me when I visited the headquarters of the Kadra trade union, which represents many of the region’s coal workers. “It’s a big problem. We are fighting, and we are losing.”

But there are degrees of losing. In July, Drobniak and members of the Kadra union had visited the British city of Newcastle as part of a tour of the U.K.’s former coal-producing regions. The location was fitting. The city in northeastern England was once a coal-mining capital whose product fueled the first phase of the Industrial Revolution. But in the early 1980s, then–British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher incapacitated the coal unions as part of the Conservative Party’s crackdown on organized labor, and the steady push toward cleaner sources of power shrank the industry. The final coal mine near Newcastle closed in 2005.

“We visited Newcastle to learn about what we should avoid in the future,” Drobniak said. “There were very poor provisions to support the people there. We saw it physically. The Newcastle area just seemed very degraded.”

Hoping that Poland could avoid a similar fate, Drobniak had already helped broker a deal with the national and provincial governments to phase out coal in waves. The talks started in early 2020, when government regulators invited a group of economists to prepare a report on what a just transition away from coal could look like. The economists came out with recommendations in May of that year and promptly began work on a national strategy in June, all while drafting regional plans for provinces such as Silesia.

To start, the agreement promised benefits to keep coal workers solvent. Under the plan, which took effect in 2021, workers can access free training to transition to other lines of work while continuing to receive some compensation from their mining jobs.

Workers who opt to quit the mining industry for good are entitled to a one-time severance payout of 170,000 Polish zloty ($47,000). Miners who are within four years of retirement and leave early can count on a salary equivalent to 80% of their typical annual earnings.

The deal that Drobniak helped broker set a deadline of 2049 for Poland’s final coal operations to shut down, years later than in many other EU nations. Not everyone supported the idea. Poland’s reliance on coal has rendered its air some of the dirtiest in Europe, shaving an average of nine months off its citizens’ lives. Its per capita greenhouse gas emissions are the fifth-highest in the EU, and Brussels has continued to pressure Poland to speed up its transition. Meanwhile, Warsaw is bristling at spending more money to keep the coal sector’s operations going for another 23 years.

Over coffee and cookies at Kadra’s modest offices on the outskirts of Katowice, in the shadow of idle smokestacks from now-defunct coal-fired plants, Grzegorz Trefon, the union’s head of international affairs, recalled a famous speech Nikita Khrushchev gave at the Polish Embassy in 1956, in which the Soviet leader vowed to defeat the capitalist forces of the world through patient confidence that “history is on our side.”

“That’s what we want,” Trefon said. “We want to win by time.”

The reference to a reviled Russian ruler drew chuckles among his compatriots in the room. Dariusz Stankiewicz, the regional government’s lead specialist on the transition from coal, stepped in to clarify what Trefon meant.

“This shows that when we are facing this in a very slow manner, our economy can transform itself and produce new workplaces,” he said.

Between 2005 and 2022, Silesia lost 55,000 jobs in the mining sector, according to government data. But the region added 160,000 jobs in other sectors during that same 17-year time period.

“If we slow down the process, the economy can cope with this problem and produce new jobs,” Stankiewicz said. “This is why I support this very slow phasing-out process.”

In Bytom, poverty is entwined with pollution. Men looking older than their years, with sinewy muscles and tattoo-covered torsos, arrive shirtless at the grocer to buy cases of beer or vodka after finishing midday shifts at the mine. Across the street from the coking plant, women visibly solicit customers for sex from the stoops of Soviet-era apartment blocks. Drobniak warned me to be ready to run if anyone seemed to be eyeing my camera.

A roughly half-hour drive east, on the northeast side of Katowice, is a neighborhood with similar-looking buildings but a dramatically different vibe. The cobblestone streets and old brick buildings of the Nikiszowiec Historic Mining District hark back to an earlier era when this part of the region was powdered with coal dust and ash from active mines and industrial sites.

Today, however, the district is spotless and filled with local tourists who come to see hockey games at its indoor rink, eat at upscale restaurants, and shop at its art galleries. A facility that once contained a major coal mine now serves as a hub for video game developers.

“This was not a place that people wanted to come to,” Drobniak said. “Now it’s hard to get a table at the restaurants here on a Friday night.”

Both Warsaw and Brussels have contributed to Katowice’s advancement over the past 20 years, as has celebrity academic Philip Zimbardo, the American social psychologist best known for the Stanford Prison Experiment, whose international work eventually led him to set up a nonprofit called the Heroic Imagination Project in the historic district in 2014. That organization worked to create employment opportunities for young people, and as conditions improved, the EU gave the city a grant of 200 million euros ($235 million) to help revamp industrial buildings for modern uses.

The starkest transformation, however, may be in the city center, where the newer industries that Silesia has attracted have flocked. While mining once accounted for more than half of the province’s gross domestic product, it now makes up a third, as factories producing automobiles, machinery, and electronics have popped up. Gleaming new office towers brandishing the logos of multinational consultancies rise between older brick buildings. Modern luxury condos with architecture one might expect in Miami or Tel Aviv but not Central Europe take up entire blocks of an otherwise quaint city. A grass-covered park swoops down to a vast, futuristic stadium built in the Soviet times. Once an area where coal was gouged from the ground, it is now a gathering space for entertainment and corporate events — part of why Katowice was recognized last year as Poland’s best city to live in.

But Katowice remains small compared with larger cities such as Warsaw and Krakow. To Drobniak, the future of Silesia should look something like Seoul or Tokyo.

A few years ago, researchers proposed the concept of the Metropolis GZM, short for Górnośląsko-Zagłębiowska Metropolia. Rather than a piecemeal approach to developing new industries in the patchwork of former coal-mining hubs that dot central Silesia, Metropolis GZM would unite the urban areas into one, interconnected with railways, bike paths, and corridors of tall buildings.

“In the entire surrounding area, we have about 2.5 million people,” Drobniak said. “We would be the biggest city in Poland.”

Merging would help solve one of the trickier elements of the transition. Bringing the entire region under one municipal planning organization would, in theory, help find ways to bridge the divide between thriving cities like Katowice and declining hinterlands like Bytom.

“People are afraid that they’ll lose their identities because they are connected by generations not with Katowice but with other cities like Bytom,” Drobniak said. “We’d like to put the discussion on a different level and say, ‘There is no Katowice. It will be something new.’ We don’t know what will be the name of this urban structure. But this is a must. We must do this. If not, we will be fragmented and separated, and the metro areas of Krakow and Wroclaw will attract young people from us.”

The critical thing, Drobniak said, is to revive the economy rather than push residents to leave, keeping the youths and workers who draw new industries and stemming the decline of Bytom and other cities.

In former American coal-mining hubs in Appalachia, such as West Virginia, generations of families remain entrenched despite the downward trajectory of the industry and the dangers of a polluted environment. But those roots are shallow compared with Poland’s, said Trefon. Miners in Silesia can trace their families in local history nearly twice as far back as 1777, when the U.S. was founded.

“My family lives here. There are churches with my relatives’ names going back 400 years,” he said. “That’s why we have so much connection to this land. It’s not possible to find another place to remake the mining industry. But we need to find a sustainable way for the development of new economic activity that will stay here.”

It might seem like a dicey time for building decarbonization in the U.S., where edifices and the energy they consume account for about a third of the nation’s annual carbon pollution.

Republicans in Congress have cancelled tax credits that would have helped households save big on clean energy upgrades. The Trump administration is dismantling federal building-decarbonization policies and trying to block states and cities from setting rules that restrict fossil fuel use in homes and businesses. Even some Democrats who once championed such mandates U-turned last year: Los Angeles’ mayor repealed an ordinance that most new construction go all-electric, and New York’s governor delayed a similar statewide law previously slated to go into effect last week.

These are very real headwinds, but they’re not the whole story. Several key barometers suggest that building decarbonization is poised to pick up speed as consumers grow more worried about energy affordability, installers get familiar with electric tech, and policymakers and building owners alike recognize the health, comfort, and financial benefits of ditching fossil fuels.

Let’s dive into seven indicators — and a few bonus figures — that show why the momentum behind climate-friendly buildings may be unstoppable.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the consumer price index for piped gas ballooned more than twice as fast as that for electricity, and nearly four times as fast as overall inflation for all tracked items. That makes utility gas one of the leading causes of inflation, which could give customers pause on whether to depend on the fuel in the future.

The price surge is partly thanks to the fact that the U.S. has been increasing its exports of liquefied natural gas, squeezing the domestic fuel supply and driving up costs at home, said Panama Bartholomy, executive director of the nonprofit Building Decarbonization Coalition.

Gas customers are also shouldering growing infrastructure costs. Utilities have massively ramped up gas-system spending since the 2010s — a result of increased safety investments in response to some high-profile explosions that decade, as well as a sense of urgency stoked by state climate laws, Bartholomy said.

“Many [utilities] view this as a race against time,” he noted in a December interview. “We now have 15 states since 2020 that have started future-of-gas proceedings, where they’re actually [taking] a regulatory approach to how they’re going to wind down the gas system in their state.”

In utility territories across 46 states and Washington, D.C., existing gas customers cover the cost of hooking up new customers to the system. The fees add up to $2 billion to $7 billion each year, according to an August 2025 analysis by the Building Decarbonization Coalition.

Policymakers and utilities in six states have reformed these “line extension allowances” to stop incentivizing growth of the gas system as well as to lower customer bills. Of the six, California, Colorado, and New York have eliminated the subsidies statewide. Another six states and D.C. are considering ending them.

Putting an end to gas-hookup subsidies is a fast-acting affordability measure, Bartholomy said. “States [that] stop subsidies in 2026 … are going to save people money in 2027.”

The majority of homes — both single- and multifamily abodes — are now built with electric heating, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That’s a big change over the last decade for single-family homes especially; in 2015, 60% were equipped with gas or propane heating, and just 39% were heated electrically.

Among multifamily buildings, electrically heated units accounted for 63% of new construction in 2015. In 2024, the share rose to 76%.

The agency doesn’t break down how many newly built homes have super-efficient heat pumps. But the next stat shows that the appliances are increasingly popular.

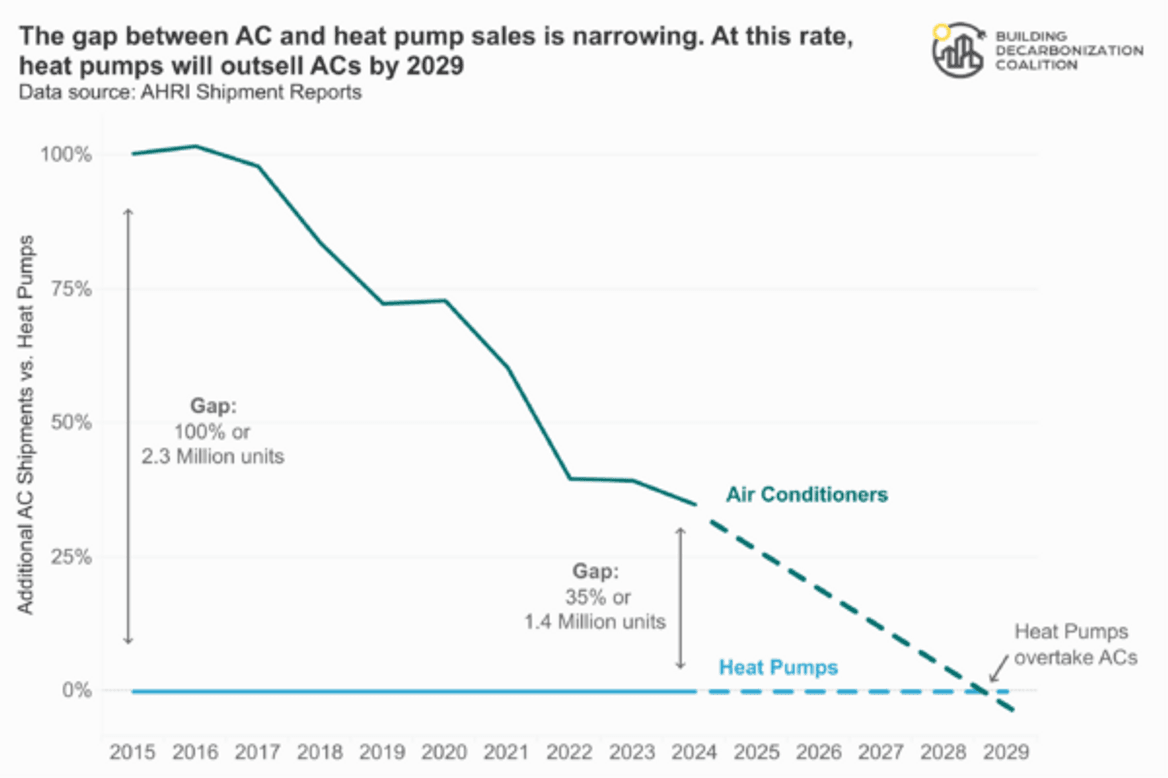

Heat pumps beat out gas furnaces (3.1 million shipped in 2024) by their biggest margin ever, 32%, that year, according to data from the industry trade group Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute. The numbers for 2025 through October, the latest available, show heat pumps in the lead yet again.

These appliances, which provide both heating and cooling, are also steadily gobbling up the market share of conventional air conditioners. In 2015, ACs outsold heat pumps by two-to-one. By 2024, the gap had shrunk to 35%, with ACs still pulling ahead.

Bartholomy of the Building Decarbonization Coalition predicts that margin could shrink to just 20% in 2026.

Lawmakers in 13 states have approved bills that encourage gas utilities to reinvent themselves as utilities that provide carbon-free thermal energy instead of fossil gas. Some of these laws require gas companies to pilot thermal energy networks, which can decarbonize entire neighborhoods at once by replacing gas pipeline systems. Others unlock financing or establish regulatory frameworks that allow utilities to recover costs for these projects from customers.

Thermal energy networks that make use of geothermal heat, found tens to hundreds of feet deep, are also the rare climate solution that the federal government is incentivizing. Geothermal networks are eligible for a tax credit of 30% to 50% until 2033. The appliances that harvest underground heat and store it for later — geothermal heat pumps and thermal batteries — qualify for the tax credit, too, as long as eligible commercial customers lease instead of purchase these products.

“In many states, we’re seeing this lease [structure] as a real tipping point, where geothermal becomes less expensive than the status quo for the builders,” Dan Yates, CEO of geothermal heat-pump startup Dandelion Energy, told Canary Media last year.

That’s according to a survey released in January 2025 by the ACHR News. The same survey revealed that 71% of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning installers expect heat pumps to make up a larger fraction of projects in the next three years. Just 61% thought so the year before.

Contractors may be responding to warming consumer sentiment. About nine out of 10 heat-pump owners would recommend the tech to others, and a growing number of homeowners (32% in 2024 versus 23% in 2023) report having a good understanding of what these systems are, per a survey published in February 2025 by manufacturer Mitsubishi Electric Trane.

Innovation in some contractor businesses could also help the tech gain traction. One vertically integrated startup, Jetson, says it’s cutting the cost of heat-pump installations in half.

That nugget comes from the National Kitchen & Bath Association’s 2025 Kitchen Trends Report, according to a September Forbes story.

“I’m a big fan of induction,” Amy Chernoff, vice president of marketing at national retailer AJ Madison, told Forbes. Compared with gas cooking, an induction stove “keeps your kitchen cooler, it’s easier to clean, better for the environment, and much safer for households with children.”

The above numbers reveal how the markets for efficient, electric equipment — nudged along by policy — are steadily transforming. Let’s see if consumers, contractors, developers, advocates, and policymakers can keep up the building-decarbonization momentum in 2026.

Last year, I made a habit of checking the live feed of a particularly pitiful webcam.

The view showed a muddy gravel lot bisected by a chain-link fence in the coastal marshes of southern New Jersey. No person or vehicle ever entered the frame, though I half expected the site to be bustling with activity as the state transformed it into a billion-dollar port for offshore wind.

Only once when I checked this live feed did I see something different. On a summer evening, I logged on and the camera panned to another angle, which showed an adjacent site where some construction work on the New Jersey Wind Port had started and then stopped. A view of the vast Delaware Bay loomed in the background. I watched the sun set over the half-built, now-abandoned port.

Some metaphors write themselves.

The Garden State megaproject, championed by former Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy, is just one offshore wind project among many that were disrupted by the Trump administration last year. Throughout 2025, the federal government clawed back federal funds, sunsetted wind tax credits, and froze permitting for wind farms. It ended the year with a bang: About two weeks ago, the administration issued a sweeping stop-work order to all five offshore wind farms under construction in the U.S.

The fall of New Jersey’s offshore wind port mirrors the fate of planned wind farms, ports, and manufacturing sites that many states, particularly in the Northeast, had spent decades building up.

Still, multiple experts told Canary Media it was inaccurate to call the industry “dead.” At least one described the state of affairs as a hibernation — and as a key time for “learning” before the next wave of activity.

According to some analysts, it’s not easy to see when — or if — that next wave of offshore-wind activity will come.

When Donald Trump was elected last November, BloombergNEF expected the U.S. to build 39 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2035. BNEF’s latest forecast, released in October, expected just 6 gigawatts to be built by 2035 — an amount equivalent to the capacity of those five wind farms that were under construction and America’s only fully completed project, New York’s South Fork.

Even that may be optimistic if Trump’s late-December stop-work order results in cancellations.

In other words, according to BNEF, it’s possible that no new wind farms will break ground in the U.S. for the next decade. Even with a recent court ruling deeming Trump’s permitting freeze “unlawful,” developers would struggle to finance projects that aren’t already underway, analysts say. It’s also hard to imagine why an offshore wind developer would bother trying to get a new project off the ground while Trump is in office, given the level of turmoil and explicit ire.

“We think the risks are inherent to the Trump administration,” said Harrison Sholler, an offshore wind analyst for BNEF.

The sector also faces cost pressures both related and unrelated to Trump.

Even before 2025, pandemic-related supply chain issues, rising interest rates, and inflation had all made it more expensive to build offshore wind in America, Sholler said. In fact, those pre-Trump macroeconomic conditions caused a few projects to collapse during the Biden administration.

But the cost issue has gotten worse, not better, since Trump was sworn in last January.

Take New Jersey’s wind port, for example: The $637 million state-backed project broke ground in 2021 and was supposed to be a staging area for two wind farms planned for the Garden State’s coastline — Atlantic Shores and Ocean Wind. Days after Trump took office, Atlantic Shores began imploding when co-developer Shell pulled out and the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities declined to grant the projects a power purchase agreement. Both Shell and the utility board cited “uncertainty” over federal actions. And in late 2023, developer Ørsted pulled the plug on Ocean Wind and its port commitments because of rising costs. The port’s fate is uncertain, and its webcam appears frozen.

Overall, “offshore wind has gotten one-third more expensive based on our modeling, and that doesn’t include the effects of tariffs,” said Sholler, who explained that the cost increases in BNEF’s latest calculations were driven by Trump’s July move to phase out federal tax credits much earlier than the date previously set by the Biden administration.

Offshore wind, as a sector, has had bad timing in the United States.

The Biden administration started issuing full project approvals about a year into the Covid-19 pandemic, which had scrambled supply chains and sent interest rates soaring. Amid these economic hurdles, the U.S. charged forward with offshore wind anyway.

Elizabeth Klein, former director of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, defended the pace at which the federal government permitted new offshore wind farm projects, even as financial conditions worsened.

“It was incredibly important to get as many projects permitted as possible so we can build some proofs of concept,” Klein said.

But that might have been a mistake, according to Elizabeth Wilson, a wind energy expert and professor of environmental studies at Dartmouth College, who said state and federal leaders should have slowed down wind development during that time instead of leaning in.

“We were building a whole new sector … Building it as rapidly as we had hoped to do was even more ambitious,” Wilson said.

America’s offshore wind industry, Wilson said brightly, is now in a “learning phase.” And considerable learning, she argues, has already happened: State governments are currently more equipped to grow and manage offshore wind power than they were five years ago.

Wilson and three colleagues published a study this month demonstrating that U.S. states, even prior to Trump 2.0, were already “drawing lessons” from the challenges they encountered while trying to launch the nation’s first offshore wind farms.

In New York, for example, state regulators adapted the way they price power purchase agreements to better account for rising costs. In New Jersey, an early oversight in transmission planning led to new requirements for offshore wind developers to show how they would better coordinate transmission across the regional power grid. And throughout the Northeast, state governors — working with federal regulators — identified better processes for compensating fishermen for lost revenue due to wind farm construction.

It’s unclear what learnings will arise from Trump 2.0, but Wilson offered a few preliminary suggestions.

First, regulatory stability is paramount, especially given the industry’s long and cumbersome permitting pipeline. Trump demonstrated how much damage can be caused by a shift in the political winds.

Though it’s impossible to guarantee political stability, Wilson suggested that state and federal regulators could, under a more hospitable future administration, revise the permitting system to at least make it faster and smoother.

After all, European energy developers, who are leaders in offshore wind, were surprised by the fragmented permitting and uncoordinated regulatory landscape they encountered in America, according to Wilson.

This kind of change might address the friction that occurs for projects trying to get approved by multiple governments, which has indeed eroded investor confidence in recent years, according to BNEF’s Sholler.

Klein agreed that coordination between states, counties, and federal agencies could improve, but she also pointed out that the current way of doing things did get results.

“Our permitting process is not broken … We got 11 projects approved,” she said, referencing her time leading the federal branch that regulates offshore wind farms during the Biden administration.

Wilson argues that another “site for learning” would be the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project, which, based on its history of strong bipartisan support, could be a “model of success.”

Klein agreed, calling CVOW, “a little bit of a unicorn.”

The project, located nearly 30 miles off the coast of Virginia Beach, Virginia, has the distinction of being America’s largest offshore wind farm and the only one that is getting built by a regulated utility. The project was slated to feed the grid starting this March — and, prior to last month’s federal pause, was progressing on schedule.

Dominion Energy, the utility building the project, operates under a “vertically integrated model,” said Wilson, giving it a long-term stability that is beneficial to slow-moving offshore wind development.

Virginia is also the world’s data-center capital, with tremendous energy demand that offshore wind is especially good at serving, especially in extreme winter conditions. Thanks to CVOW’s careful site placement and community engagement, opposition from fishermen and local groups has been relatively low, according to Captain Bob Crisher, a Virginia-based commercial fisherman.

Still, the project was ultimately not spared the major political obstacle of a Trump administration stop-work order.

Perhaps the biggest lesson, for Wilson at least, is that hyping the offshore wind industry did little good. The target dates and costs estimated were possibly “overhyped,” she said, leading lawmakers and others who turned a blind eye to the reality of offshore wind farms being, ultimately, megaprojects.

Offshore wind is a megaproject sector, and “megaproject dynamics” are well studied in Europe, said Wilson. These social and political processes are predictable, in that costs always go over, timelines typically run long, and environmental impacts are often not well communicated. Over the years, these inevitable outcomes gave influential offshore wind opponents and GOP lawmakers fodder for pushing back on offshore wind.

“This is a useful framework: Megaprojects are hard,” she said.

An enormous and novel energy storage project could soon break ground in California after receiving state approvals just before Christmas.

The startup Hydrostor’s Willow Rock project would store 500 megawatts of power that could be injected into the grid for up to eight hours, totaling 4 gigawatt-hours. That’s more gigawatt-hours than any lithium-ion battery offers, and a rare step forward for a major long-duration energy storage project. Once online, it could prove a crucial tool for California, where intermittent solar generation has become the state’s top source of electricity.

Hydrostor received permission to start building from the California Energy Commission, which signs off on environmental approvals for large thermal power plants. This has become a rarity in an era when the state pretty much exclusively builds solar and battery plants. Hydrostor, however, compresses air in underground caverns and then releases it to turn conventional turbines and send power back to the grid. Its roster of equipment put the project under the commission’s jurisdiction.

“These are the major approvals. It basically allows us to get to a shovel-ready status,” Jon Norman, president of Hydrostor, told Canary Media.

That means Hydrostor can technically begin construction on the 88.6-acre parcel it controls, where rural Kern County hits the Mojave Desert.

But Hydrostor won’t actually start building until it secures paying customers for the full planned capacity. So far, Central Coast Community Energy has contracted for 200 megawatts of Willow Rock’s capacity. Hydrostor is negotiating contracts for another 50 to 100 megawatts, which leaves 200 to 250 megawatts up for grabs.

That uncontracted capacity stands in the way of Hydrostor securing the financing it needs to pay for the roughly $1.5 billion project. Lenders or investors want assurances that the innovative installation will make enough money to pay them back, with a return. Otherwise, the project is exposed to merchant risk: Maybe Hydrostor could build it anyway, bid into the wholesale markets, and make good money. But that’s too risky a bet for most financiers, who want to see firm customer commitments.

Two factors further complicate the pitch to financiers. Because Hydrostor is trying to build a fundamentally new type of storage plant, there isn’t a clear market comparison to benchmark against. And it’s also competing in a fundamentally new type of market niche: long-duration storage.

Many analysts have predicted the physical need for longer-term grid storage as more and more of a region’s electricity comes from wind and solar power. Few regions have developed workable market structures to get ahead of that need, since today’s power markets focus on short-term optimization rather than long-term infrastructure planning.

California, though, has supplemented its power markets with a centrally driven push for long-duration storage. The state’s utility regulator required power providers to procure a collective 1 gigawatt of storage that lasts for eight or more hours. That order prompted Central Coast Community Energy to sign the deal with Hydrostor.

In September, the California Public Utilities Commission recommended a portfolio including 10 gigawatts of eight-hour storage for 2031, as part of the state’s planning for its transition to 100% clean electricity. That means a procurement order could come soon, and Hydrostor, with its permits in order, would be in position to compete for that.

“They’ve identified the need for very near-term procurement, so we’re looking forward to participating in that,” Norman said. “We also know that we’re very competitive.”

He also said it’s “very likely” that Hydrostor breaks ground this year.

That would kick off an estimated four-to-five-year construction timeline, Norman said. The company has created a “pretty sophisticated Joshua tree management plan” to protect the alien-looking vegetation unique to the Mojave, where it will build the project. It also secured a water supply and place to deposit the rock it carves from the earth, and it is currently finalizing an engineering, procurement, and construction contractor, Norman said.

That timeline should put Willow Rock in a good place to help California meet those medium-term storage needs. Given current trends, in five or so years the state will be even more awash in surplus solar generation at midday, and in even greater need of on-demand energy to keep the lights on after the sun sets.

In other words, if the regulator’s numbers are right, California will need many more Willow Rocks to keep up, so it’s about time one of them got going.

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

U.S. energy markets and policy are heading toward the equivalent of a multicar pileup in 2026.

The key factors are consumer frustration with rising energy prices, Trump administration policies that are making the problem worse despite promises to make it better and a growing awareness that investment in AI data centers is part of a bubble that could pop at any time.

I asked seven experts for their outlook on what we’ll be talking about in 2026 and almost all of them touched on this set of intertwined problems. Call it a crisis or a disaster. Or just call it terrible politics for the party in power ahead of November’s midterm elections.

Robbie Orvis, senior director for modeling at the think tank Energy Innovation, said he expects energy affordability to be the major issue of the year. He pointed to the rising wholesale price of natural gas and how that is likely to translate into higher utility bills, since gas is the country’s leading fuel for power plants and home heating.

“I don’t anticipate that people’s home energy bills are going to go down anytime soon,” he said.

The country’s benchmark price of natural gas has risen from an average of $2.19 per billion BTUs in 2024 to forecasts of $3.19 in 2025 (full-year figures for 2025 are not yet available) and $4.01 in 2026, according to the Energy Information Administration’s short-term outlook.

Gas prices are rising for many reasons, including an increase in exports of liquified natural gas, mainly to Europe, and growing demand from U.S. gas-fired power plants.

Orvis also highlighted the Trump administration’s policy of requiring old coal plants to remain online, even when their owners would otherwise have closed them for economic reasons. The administration has done this several times, citing the need to maintain the grid’s reliability during periods of high demand.

The result is that utilities are forced to operate plants they wanted to close, which are dirtier and more expensive than readily available alternatives.

Meanwhile, the least-expensive option for new power plants in most of the world is utility-scale solar. Even if we include the cost of batteries to allow solar to be stored for nighttime use, solar is a low-cost leader, as shown by research that includes a report last month from energy think tank Ember.

The federal government could respond to rising prices by rapidly building new power plants. But the country’s permitting system, supply chains and recent policy decisions are harming the ability to provide relief.

Some of these problems predate the Trump administration. But President Donald Trump has made things worse with executive orders that add restrictions on the development of wind and solar power, including a stop-work order in December that halted construction on five offshore wind projects.

Michael Webber, a professor of engineering and public affairs who studies energy at the University of Texas at Austin, puts this problem in the form of a question:

“Do we return to normal for permitting energy projects or will every project have to price in the risk that the president might impulsively cancel it?” he asked in an email.

He said this risk is a cost driver for developers that will be enough to stop some marginal projects and drive up rates for consumers.

Our crystal balls are not super precise on some topics. For example, several people said the investment in AI data centers and forecasts of rising electricity demand to power them are part of an investment bubble. But it’s unclear if this market will face its reckoning in 2026 or later.

The larger problem is that AI companies are spending tens of billions of dollars to build gigantic, energy-sucking data centers, often without clear plans for how these projects are going to make money.

“There’s a bubble, and what’s going to end up happening is there’s going to be a consolidation,” said Stephen A. Smith, executive director of the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, an advocacy group based in Knoxville, Tenn.

In a consolidation, the companies with the weakest business plans will go bust and the companies with viable plans and ample cash reserves will pick over the wreckage.

One of the main questions, Smith said, is how much consumers will need to cover the costs of unwise investments to power data centers.

The worst-case scenario would be if utilities make substantial investments to meet data center demand and the demand doesn’t fully materialize, leaving the costs to be paid by households and other consumers.

Some states, including Indiana and Ohio, have adopted rules to try to make data center developers assume much of this risk. But much of the country has yet to thoroughly explore what happens to utilities and their consumers in a data center bust.

State utility commissions have helped set the table for the affordability crisis by approving rate increases and spending that push the limits of what ratepayers can afford.

Commissioners, along with governors and members of state legislatures, “are finally taking heed of their policy missteps,” said Kent Chandler, senior fellow for the think tank R Street Institute and former chairman of the Kentucky Public Service Commission.

Chandler expects that some state-level discussions will focus on introducing competition in areas where utilities now have local monopolies, with the hope that market forces can help contain costs.

At the same time, states and regions that already allow competition in electricity and natural gas markets may go in the opposite direction and explore giving utilities more leeway to build power plants and pass costs on to consumers.

If this sounds disjointed, that’s because it is. The larger point is that officials will respond to frustration with rising prices by wanting to be seen as taking action.

The decision by Congress and Trump to eliminate consumer tax credits for electric vehicles will cast a pall on at least the first half of 2026 and maybe longer. The credit phaseout in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act last summer led to a sudden surge in EV purchases before the incentives expired at the end of September, followed by an expected drop-off in sales.

“We’re going to see sales be a bit more tepid,” said Mryia Williams, executive director of Drive Electric Columbus in Ohio.

The problem is that potential buyers “are not sure what’s going on with anything,” she said.

Automakers have some high-profile EVs coming this year, including the redesigned Chevrolet Bolt and the new Rivian R2. But some companies also are reducing and redirecting their funding for EVs, including Ford, which discontinued the F-150 Lightning pickup as a fully electric model and is replacing it with a gas-electric hybrid.

Williams has concerns that eliminating tax credits sends the wrong message to automakers and consumers at a time when other countries are moving ahead of the United States in building the vehicles of the future. That said, she remains confident that the world will make a near-complete shift to EVs, even if U.S. policymakers decide they want to move more slowly.

It’s normal for the party that’s not in power to gain seats in Congress in the first midterm election after a presidential election. And, considering that Republicans’ majority in the U.S. House is fewer than five seats, it would surprise nobody if Democrats win control of the chamber.

The larger questions are about the scope of Democrats’ gains, including whether the party will pick up enough seats to gain control of the U.S. Senate and make substantial progress in governor’s offices and state legislative chambers.

A big part of the answer will depend on how effectively Democrats communicate their agenda in terms of voters’ affordability concerns, said Caroline Spears, founder and executive director of Climate Cabinet, an advocacy group that supports pro-climate candidates in state and local races.

“Voters are angry about rising prices, and we have an undercurrent of instability in the economy that has become more of a feature rather than a bug in the last few years,” she said.

Spears’ organization is focusing on states such as Arizona, Michigan, Minnesota and Pennsylvania, where flipping just a few seats could make a big difference on climate and energy policy.

She highlights Arizona as a state with a huge upside in terms of Democrats being close to having enough control to unlock more of the economic benefits of solar power.

“The extreme anti-clean energy legislation we’re seeing out of the sunniest state in the country is just astonishing,” she said.

To underscore this point, she noted that Massachusetts has more solar power jobs than Arizona, a fact that should be upsetting to Arizonans.

Now it’s time for the closer: Amory Lovins, an engineer and cofounder of RMI, has done about as much as anyone to foster research and advocacy about energy efficiency and conservation.

I saved him for last because the discussion of rising energy demand should, and could, turn into one about the need for greater efficiency.

Efficiency can take many forms, including batteries with higher energy density, solar panels that can capture more sunlight and computer servers that require less electricity to perform the same tasks.

He expects to see progress in 2026 but thinks more about how actual progress compares to what could be achieved with the right investment, research and policy support.

The obstacles aren’t technical or economic, he said. They’re mainly cultural and institutional.

“This is not low-hanging fruit that you harvest and then it gets scarce and expensive,” he said. “This fruit has fallen off the tree and is mushing up around our ankles, rotting faster than we can harvest more.”

He didn’t discuss efficiency in partisan terms, but I will. We have a president who has taken steps to weaken government requirements that products become more efficient, casting this as a matter of consumer choice. Trump said in his “Unleashing American Energy” executive order that he is safeguarding “the American people’s freedom to choose from a variety of goods and appliances” including lightbulbs, dishwashers, washing machines, gas stoves, water heaters, toilets and shower heads.

While Trump said this is a consumer-friendly action that will save money, decades of research on efficiency standards show the opposite to be true. The Trump administration has said its actions on the standards will save $11 billion, but this is based on an estimate of the cost of the rules that doesn’t include savings on utility bills. If we consider the costs and benefits, the standards have a net savings of $43 billion, according to an analysis from the Appliance Standards Awareness Project.

So, in an election year amid an energy affordability crisis, one side is actively hostile to energy affordability.

Other stories about the energy transition to take note of this week:

Offshore Wind Developers Seek Quick Court Resolution to Allow Construction to Resume: Ørsted and Equinor, two of the companies building offshore wind farms, have gone to court to seek permission to resume construction of two large projects that were stopped by a Trump administration order, as Diana DiGangi reports for Utility Dive. This is in addition to Dominion Energy’s request that a court allow it to resume work on a separate offshore wind farm, which will be the subject of a hearing next week. Interior Secretary Doug Burgum had ordered a stop to construction last month, saying there is new evidence that offshore wind could pose national security risks, but he didn’t go into detail about the risks.