Electric trucks can beat diesel-fueled ones on the cost of moving freight from California’s seaports to its inland distribution hubs — as long as the battery-powered vehicles can reliably recharge at both ends of their route. That fact is spurring a boom in the construction of truck-charging depots across the state.

On Thursday, EV Realty, a San Francisco-based charging site developer, broke ground on what will be one of California’s biggest fully grid-powered, fast-charging depots for electric trucks so far.

The company’s site in San Bernardino, located in a region known as the Inland Empire that’s crowded with distribution warehouses, will pull about 10 megawatts of power from the grid once it’s up and running in early 2026. It will be equipped with 76 direct-current fast-charging ports, including a number of ultra-high-capacity chargers capable of refilling a Tesla Semi truck in 30 minutes or less.

EV Realty has more large-scale depots in the works, including another in San Bernardino, one in Torrance near the Port of Long Beach, and a fourth in Livermore in Northern California. Thursday’s groundbreaking was accompanied by the announcement that the company had raised $75 million from private equity investor NGP, which also led a $28 million investment in 2022.

With that cash infusion, along with last year’s debut of a joint venture with GreenPoint Partners to develop $200 million in charging hubs, “we are fully capitalized against an underwritten, five-year business plan,” EV Realty CEO Patrick Sullivan told Canary Media.

That plan includes “five to seven more projects of the scale we have in San Bernardino, plus some smaller, more built-to-suit projects,” he said.

EV Realty does build and operate sites for passenger vehicles, such as the chargers it installed in a parking garage in Oakland, California, backed by power provider Ava Community Energy. But the company isn’t in the business of setting up open public charging sites that depend on drive-by traffic to earn money back, Sullivan said.

Instead, it’s signing deals with major freight carriers and fleet owners that want a dedicated spot to get their trucks charged and back on the road as quickly as possible.

That’s why EV Realty’s 76 chargers at its San Bernardino site are all dedicated to specific customers, he said. Of those, 72 are committed to those paying monthly rates on multiyear contracts. “Our customers will have stalls and amounts of power that are theirs 24/7, and we will have customers basing their operations out of that site,” he said.

The remaining four chargers, including those offering high-voltage megawatt charging systems, are “pull-through” slots where trucks towing trailers can get a quick recharge. “That pricing will be more of a pay-as-you-go, per kilowatt-hour — but all those trucks are registered at our site,” he said.

EV Realty is far from the only business building megawatt-scale truck-charging sites in California. Big EV truck depots are springing up around Southern California’s massive port complexes and along its major freight corridors, built by startups such as Terawatt Infrastructure, Forum Mobility, Voltera, WattEV, and Zeem; freight haulers like NFI Industries and Schneider National; and logistics operators such as Prologis.

Most of these depots are providing dedicated service to customers under contracts, but a few are starting to offer charging on a first-come, first-served basis. Greenlane, a joint venture of Daimler Truck North America, utility NextEra Energy, and investment firm BlackRock Alternatives, opened a 10-megawatt truck-charging site in Colton, a city neighboring San Bernardino, that’s meant to provide a more traditional “truck stop” service to vehicles needing to charge.

If anything, EV Realty has been “a little bit more slow and purposeful than others” in building its charging hubs, Sullivan said. But he insists that the broader truck-electrification project remains economically viable, despite the challenges erected by the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress.

There’s no doubt that electric trucking is experiencing a tough moment in California and across the country. The megalaw passed by Republicans in July cut short tax credits for commercial EVs and EV chargers that had been put in place by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. This has weakened support for purchasing battery-powered vehicles, which still cost two to three times more than their fossil-fueled counterparts, even if EVs’ lower fueling and maintenance costs can make them cheaper in the long run.

This summer, Republicans and the Trump administration also revoked Clean Air Act provisions that permitted California and 10 other states to set mandates forcing manufacturers to sell increasing numbers of zero-emissions trucks. Last month, major truck manufacturers sued California, seeking to extricate themselves from a clean-vehicle partnership agreement.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration’s trade policies have thrown “sand into the works” of the U.S. freight industry, Sullivan said. Imports are set to decline significantly under President Donald Trump’s tariffs on foreign-made goods, and the on-again, off-again nature of his taxes has scrambled long-term planning.

“Carriers, trucking, transportation companies are at the very front lines of a global trade war,” Sullivan said. “You have no predictability on how you can utilize your assets.”

In the face of that uncertainty, cementing charging for electric trucks along established routes becomes more important than ever, he said. Like many of its charging depot competitors, EV Realty is inking partnerships with other parties in the broader freight-hauling industry, such as its August agreement with Prologis to share and streamline access and software systems across both companies’ networks.

With dedicated charging in hand, freight companies and their customers can start to realize the underlying competitive economics of electric trucks, Sullivan said. “A carrier bidding on freight on a lane is bidding whatever their marginal operating cost is, above or below the cost of fuel,” he said. “If you can move short and regional haul, point to point, with an EV, you’re bidding on a marginal cost that’s lower than diesel.”

Cleveland has big ambitions to reduce its planet-warming emissions. But a massive steelmaking facility run by Cleveland-Cliffs, one of Ohio’s major employers, could make it difficult for the city to see those plans through.

The plant emits roughly 4.2 million metric tons of greenhouse gases each year, complicating Cleveland’s effort to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, according to a report released by advocacy group Industrious Labs this summer. The plant is the city’s largest single source of planet-warming pollution.

Cleveland’s climate action plan is “bold and achievable,” said Hilary Lewis, steel director for Industrious Labs. But “if they want to achieve those goals, they have to take action on this Cleveland Works facility.”

As a major investment decision looms over an aging blast furnace at the facility, it’s unclear whether the company will move to cut its direct greenhouse gas emissions — or opt to reinvest in its existing coal-dependent processes.

Cliffs’ progress in reducing its nationwide emissions earned it recognition as a 2023 Goal Achiever in the Department of Energy’s Better Climate Challenge. As this year began, the company was set to slash emissions even further through projects supported by Biden-era legislation — the Inflation Reduction Act and the 2021 infrastructure law.

Then the Trump administration commenced its monthslong campaign of reneging on funding commitments for clean energy projects, including ones meant to ramp up the production of “green” hydrogen made with renewable energy. In June, Cliffs’ CEO Lourenco Goncalves backed away from a federally funded project to convert its Middletown Works in southwestern Ohio to produce green steel, saying there wouldn’t be a sufficient supply of hydrogen for the plant.

To Lewis, coauthor of the Industrious Labs report, that’s a weak excuse, because hydrogen production by other companies would have ramped up to supply the facility. “[Cliffs was] going to need so much hydrogen that they would be creating the demand,” she said.

Meanwhile, Cliffs’ Cleveland Works continues to spew emissions that drive climate change and harm human health. Industrious Labs’ modeling estimates that pollution from Cleveland Works is responsible for up to 39 early deaths per year, more than 1,700 lost work days, and more than 9,000 asthma cases. Cleveland ranks as the country’s fifth-worst city for people with asthma, according to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America.

Cleveland Works’ Blast Furnace #6 is a hulking vessel that removes impurities from iron ore by combining it with limestone and coke, a form of coal that burns at very high temperatures. Industrious Labs’ report notes the unit’s lining is nearing the end of its useful life.

To Industrious Labs, this presents an opportunity: The company could replace the old infrastructure with equipment that can process iron ore with natural gas or hydrogen instead of coal. Investing in this technology, called direct reduction, would cut the plant’s greenhouse gas emissions by more than 30% if natural gas is used. Using green hydrogen would slash emissions even more, the Industrious Labs team found.

The alternative is to just reline the furnace, which was the course Cliffs chose for the Cleveland facility’s Blast Furnace #5 in 2022.

Relining might provide small emissions cuts when measured per ton of steel, due to increased efficiencies, Lewis said. But ramped-up production from running more ore through the furnace could offset those reductions or even increase total emissions.

Cliffs did not respond to Canary Media’s repeated requests for comment for this story, and it has not yet publicly announced its plans for Blast Furnace #6.

To put itself on track with Cleveland’s emissions goals, however, the company would need to do more than just convert Blast Furnace #6 to the direct reduction process, Industrious Labs said.

The next step in the road map the group laid out would be for Cliffs to process refined iron ore into steel with an electric arc furnace — which can run on carbon-free power — instead of using the current basic oxygen equipment. Investing in green-hydrogen-based direct reduction and an electric arc furnace, instead of relining Blast Furnace #6, would increase emissions cuts to 47%, according to the Industrious Labs report.

Later steps would use direct reduction of iron and an electric arc furnace to refine and process the ore that is currently handled by Blast Furnace #5. Completing that work would cut Cleveland Works’ greenhouse gas emissions by 96%, according to the report.

The Industrious Labs analysis appears to lay out a credible decarbonization pathway, although not necessarily the only one, said Jenita McGowan, Cuyahoga County’s deputy chief of sustainability and climate. Cuyahoga County, which includes Cleveland, also has a goal of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and is in the process of finalizing the latest version of its climate action plan.

“My question about the paper is how feasible it truly is that Cleveland-Cliffs will deploy it in the near future,” McGowan said. Policy uncertainties at the federal level further complicate matters, she added.

For now, the city and county seem to be taking a pragmatic approach, focusing on achievements to date and encouraging future cuts wherever companies will make them.

But getting to net-zero for the industrial sector “will require more fundamental changes … [which] will take place over decades, rather than over a few years,” Cleveland’s climate action plan says. It also notes that low-carbon steel costs 40% more to produce compared to standard methods, “making it difficult for steelmakers to justify the investment in clean production.”

Cuyahoga County’s draft climate plan highlights Cliffs’ energy-efficiency improvements, including Cleveland Works’ use of some iron from the firm’s direct reduction plant in Toledo, Ohio. Cleveland Works also leverages much of the waste heat from its industrial activities to make electricity. The facility recently boosted that combined-heat-and-power generation by about 50 megawatts, the plan notes. That replaces electricity the plant would otherwise need from the grid, a majority of which still comes from fossil fuels.

Faster emissions reductions are certainly better, McGowan said. But the county also wants to make sure companies can stay in business as they decarbonize — especially Cliffs, one of the largest sources of commerce at the city’s port.

In Lewis’ view, decarbonizing Cleveland Works earlier rather than later would be a smart business move for Cliffs. “I think the biggest thing is staying competitive,” Lewis said.

One of Cliffs’ largest markets is supplying high-quality steel for automobiles, including electric vehicles, she added. In March, Hyundai announced plans to invest $6 billion in a new plant in Ascension Parish, Louisiana, that will produce low-carbon steel. As automakers face global pressure to source cleaner metal, Cliffs could find itself left behind, Lewis suggested.

The Industrious Labs report “opens the door for Cleveland to be a leader in clean steel,” Lewis said. Before that can happen, though, “there’s a lot of work to do.”

California’s Legislature has approved a slate of policies aimed at curbing high and rising electricity costs, involving everything from short-term relief for high summertime utility bills to public financing of transmission grids — a big accomplishment in the waning days of the session.

The affordability measures emerged as part of a sprawling energy and climate package negotiated by legislative leaders and Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office last week and passed by lawmakers Saturday. Newsom, a Democrat, now has until Oct. 12 to sign the bills into law.

“It’s just a massive end of session,” said state Sen. Josh Becker, a Democrat whose bill, SB 254, was included in the package. “We had all these planes in the air. Are they all going to crash, or are they going to land?”

Becker hopes the provisions in SB 254 will contain rapidly rising costs for the state’s three biggest utilities — Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric — which are in turn driving up rates for their customers. Those residents now pay roughly twice the U.S. average for their power, and nearly one in five are behind on paying their energy bills.

“Energy affordability was understood to be one of the top issues the Legislature needed to act on, due to massive rate increases and widespread customer outrage,” said Matthew Freedman, staff attorney at The Utility Reform Network, a consumer advocacy group that supported SB 254.

Among other things, that legislation aims to rein in how much utilities spend hardening their grids to reduce the risk of sparking wildfires, a major factor in cost increases. To that end, the bill would prohibit utilities from earning profits on some of the investments they make in wildfire-related upgrades.

It would also create a new “transmission accelerator” that enables utilities to use public financing to expand the state’s high-voltage grid rather than recoup those expenditures by charging customers. Those savings will take longer to kick in but could add up to billions of dollars a year, said Sam Uden, managing director of Net-Zero California, an advocacy group that cowrote a report last year examining how much utilities could save by relying on public financing.

“There’s a strategic role for public-sector investment to drive the clean energy transition,” he said. “We see this transmission financing as an embodiment of that viewpoint.”

SB 254 ended up as a 136-page document with a multitude of energy and climate provisions, Becker told Canary Media last week. But he highlighted one set of key cost-containment measures that the utilities had particularly resisted.

Utilities typically earn a profit by receiving a return on the investments they make in grid upkeep. Now, though, California’s big three utilities will have to finance a portion of what they spend hardening their grids via bonds — a process known as securitization.

Utilities “were kicking and screaming on that,” Becker said.

The amount to be financed through bonds was initially set to be $15 billion for all three utilities. But Freedman suggested that the utilities might have used their political clout last week to negotiate the final securitization requirement down to $6 billion, which is “a pretty big reduction,” he said.

Regardless, securitizing a portion of the growing grid-hardening costs will reduce pressure on utilities to increase rates in the future, said Merrian Borgeson, California policy director for climate and energy for the Natural Resources Defense Council, which supported the legislation. “I don’t know what the rates are going to be next year, but they’ll be lower,” she said.

Enabling public financing of transmission projects could deliver even more savings over time, Borgeson said. The “transmission accelerator” created by SB 254 for that purpose would be based out of the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GO-Biz). That entity would be authorized to pool state funds drawn from California’s cap-and-trade program and from a climate bond passed last year to lower the cost of capital for transmission projects.

The California Independent System Operator, which manages the state’s grid, estimates that California must invest between $46 billion and $63 billion into transmission over the next 20 years to meet its goal of achieving a carbon-free grid by 2045. Using public money to offset a portion of utilities’ capital spending on those projects could cut the costs of the currently planned long-range transmission buildout by more than half, saving customers as much as $3 billion a year, according to an October report from Net-Zero California and the Clean Air Task Force.

Just how much money could be saved will depend on how the accelerator structures its public-private financing, Freedman said. “SB 254 leaves open a range of possible outcomes on this front,” he added. “It depends on the ambitiousness of the implementation by this and future governors.”

The final days of this year’s session also saw lawmakers reauthorize the state’s decade-old cap-and-trade program, an initiative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that was set to expire in 2030. AB 1207 and SB 840 would extend the program through 2045 and make a number of changes with significant implications for polluting industries, though regulators and lawmakers still need to work out the exact structures for executing the new rules, Borgeson said.

The bills also take an initial stab at reallocating funds raised by the cap-and-trade system to the myriad state programs and industry sectors jockeying for the money.

For example, one key affordability measure in AB 1207 institutes important changes to the “climate credit” now paid to utility customers out of funds collected from the cap-and-trade program.

Today, those credits are delivered to customers in twice-a-year lump-sum rebates. Under the new structure created by AB 1207, those rebates can be redirected to specifically help lower utility bills during summer months, when air conditioning drives up power consumption.

“Just think about the Central Valley,” Becker said during a virtual town-hall event in June, referring to a region of California that’s both hotter and poorer than the rest of the state. During summer heat waves, “it’s 100 degrees all day — and sometimes all night — in those areas. It’s literally a matter of life and death to keep the air conditioning on.”

AB 1207 will also redirect climate credits issued to gas utilities to support lowering summer electrical bills exclusively, through a process to be worked out by California utility regulators, Borgeson said. (Today, both gas utilities and electric utilities issue climate credits to their customers.)

That provision was strongly opposed by Sempra, the holding company of San Diego Gas & Electric and Southern California Gas Co., the state’s biggest gas-only utility. In an opposition letter, Sempra said the shift would create a “statewide subsidy requiring gas customers to fund bill relief for electric customers, worsening the high cost of living in California for millions of families.”

But climate advocates say the legislation aligns with California’s goal of shifting customers from using gas to using electricity. “This is a good idea, because it doesn’t need any more money,” Juliet Christian-Smith, Western states program director at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told Canary Media in July. Instead, “it’s redirecting money already in a pot to reduce electricity rates and enable the clean energy transition in a more affordable way.”

The U.S. does not have a big enough power grid to accommodate rising energy demand — a fact that’s making electricity less affordable and reliable nationwide.

But there’s broad public support for growing the grid and allowing more electricity, including cheap, clean energy, to come online.

So says a new survey of likely voters in Ohio and Pennsylvania — two states in the severely backlogged PJM Interconnection grid region — and Arkansas, Mississippi, and Missouri, which are covered by the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO). The survey was conducted by polling firm Cygnal on behalf of the Conservative Energy Network.

Roughly three-fourths of likely voters support expanding the electric grid, the survey found. About two-thirds are in favor of adding more transmission lines to connect clean energy and strengthen grid reliability.

And nearly 90% of respondents are concerned about rising energy costs. A majority of surveyed Republicans, Democrats, and Independents said they are “very concerned.”

“This is not a partisan issue. … You don’t have to appeal to one side or another,” said Chris Lane, a senior partner at Cygnal, who previewed the findings at the National Conservative Energy Summit in Cleveland on Aug. 25.

He noted that the results stand out for their consistency between regions and among different groups — including political parties. Even so, the Trump administration has in recent months worked against grid expansion, not toward it.

Energy costs are climbing in part because of rising power demand from data centers and the electrification of buildings and vehicles. Bringing more electricity generation online — especially quick-to-build, low-cost wind and solar — could increase competition and lower prices under the basic principles of supply and demand.

But just as transportation planners need to make sure highways can handle increased road traffic, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and regional transmission operators need to make sure the grid has room for more electrons. That calls for more “lanes” in the form of added transmission lines, plus technologies to squeeze more capacity out of the system overall.

Currently, “there aren’t enough power lines, they’re not all in the right places, and the ones we have are too outdated to meet the rising power demand for electricity,” Evelyn Robinson, director of PJM affairs for the renewable-energy industry group MAREC Action, said during a separate panel at the conference in Cleveland.

While all of the United States faces delays in getting new energy onto the grid, the problem is worst in the PJM region, where hundreds of projects have been stalled in the queue for years. To deal with the backlog, the grid operator switched to a new interconnection process in 2023; as of June, PJM still had about 63 gigawatts of power, mostly clean energy, stuck in that “transition queue.”

Across the country, wind, solar, and battery storage make up most of the resources waiting to come online, and their “levelized cost of energy” is cheaper or on par with other electricity sources.

The Trump administration has called for “the rapid and efficient buildout” of energy infrastructure, including transmission lines and grid-enhancing technologies, “by easing Federal regulatory burdens.”

But the administration’s actions have so far had the opposite effect. A February executive order calling for review of independent agency rulings threatens the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s ability to expand transmission. And in July, the Trump administration canceled a $4.9 billion loan guarantee for the Grain Belt Express — the largest transmission line underway in the United States. The project aims to shuttle gigawatts of wind and solar power from the Great Plains to the East, and Sen. Martin Heinrich, D-N.M., has called the cancellation of its federal loan guarantee illegal.

The administration’s policies, including the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, are also expected to more than halve the amount of clean energy built over the next decade, further exacerbating concerns about soaring power prices and rising demand.

The survey results may help the Conservative Energy Network convince decision makers to take steps to expand the grid.

“To the best of my knowledge, this is the first poll that’s been done in the PJM area testing these things, and in the MISO south area,” said John Szoka, the group’s CEO, at the National Conservative Energy Summit.

The polling also gauged the persuasiveness of four statements to support grid expansion. The takeaways could inform how advocates and legislators work to boost public support for clean energy.

Among conservatives in Ohio and Pennsylvania, a message focused on lower costs was about 12 times more likely to shift someone’s opinion than one about preventing blackouts, Lane noted. Messages about increasing American energy production, preventing blackouts, and providing positive job and economic impacts for Americans were more likely to move liberals than one about lowering costs.

Opinions were more divided on whether the federal government, states, or private companies should pay for grid expansion, although a slight majority of respondents in both the PJM and MISO areas said they would be willing to pay a few dollars more per month in the short term if it would reduce outages and lower costs over time.

Respondents were also mixed on who should get to choose how electricity is produced. States, landowners, and local officials all ranked above federal authorities.

Clean energy, meanwhile, received only modest support on its own. About one-fourth of the Ohio and Pennsylvania respondents said using clean energy was one of their top two policy goals, with nearly one-fifth of those surveyed in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Missouri giving that response.

Ultimately, affordability and reliability were the clear consensus energy policy priorities for poll respondents in both the PJM and MISO areas.

With the federal government standing in the way of both grid expansion and clean energy development, however, it will be tough for the voters to get the improvements they want.

LAS VEGAS — There were plenty of reasons to think that this year’s RE+, the U.S. solar industry’s biggest annual gathering, would be a gloomy and downtrodden affair.

The Trump administration had declared an energy emergency, then set about reducing energy supply by going after renewables projects. The massive spending law yanked nearly seven years of tax credits for wind and solar. The White House arbitrarily halted construction on two major offshore wind farms that had all their permits in order, raising the fear that it might block other fully approved projects. Tariffs have changed the price of parts that go into clean energy equipment on a sometimes weekly basis. The cleantech bankruptcies have been relentless: Powin, Sunnova, Mosaic, Northvolt, Li-Cycle, Nikola, to name a few.

“I can’t think of a time when we have been subject to quite as much of a brutal swing as we’ve been in now,” said Abby Ross Hopper, president and CEO of the Solar Energy Industries Association, which puts on the conference.

But when I got to the exhibit hall at the Venetian Expo, it stretched farther than I’d ever seen at a clean energy show, and I heard rumors of additional halls above and below. The exhibitors even sprawled across a sunwashed bridge to Caesar’s Forum, where vendors of flow batteries and other alternative technologies hawked their wares, quite fittingly, from the periphery of the event.

Final attendance for the show hit 37,000, just shy of the record 40,000 from the previous two years, and other metrics broke records. The mood on the floor, in the halls, and at the myriad Vegas afterparties reflected an industry that had taken some punches, had lost some nice things, but was nonetheless charging forward, resolute and battle-tested.

“If you’d asked me in May how I was feeling about RE+, I would have a very different answer,” Hopper noted at a roundtable with journalists a few days into the show. “But we have more exhibitors than we’ve ever had in our history, and we have more registration revenue than we’ve ever had in our history. … [People] are really, really hungry for information and for a vision for what’s coming next.”

Judging by this year’s dire headlines, the show’s ebullient atmosphere does not seem entirely rational. Of course, even teetering startups try to project confidence among peers, customers, and especially journalists. And the overstimulated Vegas backdrop inspires a particular strain of optimism, the kind that encourages you to light cash on fire and feel lucky for the opportunity.

But after three days of roaming the frenetic halls, I came to see this year’s positive outlook as warranted. The general consensus among conference goers seemed to be that though political headwinds are blowing hard, economic tailwinds are blowing harder. Here are three reasons why I think they are right.

With the federal tax credits cut short, fewer solar projects will get built, and costs will rise for the ones that still go forward, passing on higher energy bills to American consumers.

But, with a little distance from the sting of this summer’s legislative setbacks, many solar and energy storage professionals believe losses in the policy arena are counterbalanced by increasingly rosy outlooks in the marketplace.

“I think people tend to over-orient on the policy story, and under-orient on the economic and financial story,” said Alfred Johnson, CEO of the clean energy financing platform Crux, as we sipped espressos outside the hubbub of the cavernous expo halls.

Johnson’s company launched as a marketplace for tax credit transferability, which was created by the Inflation Reduction Act, but has expanded into other forms of financing, like debt and tax equity. That perch gives him visibility into clean energy project economics and the flows of capital into the sector. He ticked off a series of key factors defining the current energy market: Electricity prices are way up; solar and battery keeps getting cheaper while improving performance; gas prices are rising as the Trump administration promotes exports; gas turbine prices are rising due to intense competition from buyers.

In short, it’s a bad time to be someone who uses electricity in America, despite President Donald Trump’s campaign promise to cut energy prices. That means, though, that it’s a great time to be someone who sells power.

Even better for power producers, the biggest new customers — data centers — have the price sensitivity of a ravenous grizzly bear. They’re trying, with the enthusiastic support of the White House, to win a global arms race to unlock artificial superintelligence, whatever that means. Facing such civilizational stakes, the hyperscalers aren’t going to quibble over nickels and dimes.

Even with elevated electricity prices, hyperscalers still have to pay a lot more for the “graphics processing units” that train and run their AI models, Johnson noted. And once they’ve paid for those GPUs, they want to use them as much as possible, which means gobbling up as much electricity as they can get.

“The value of being faster on delivering the model … is worth so much more … than the additional cost of energy, which means that the marginal demand in a lot of these markets is the data centers, who are not price sensitive,” Johnson said.

Solar is clearly the cheapest source of new electricity production. But what matters most now is speed to market, and here solar and batteries easily trounce all other commercially viable sources of power. Taking mass-produced panels and parts and assembling them in a field is fundamentally easier than constructing a traditional large power plant. And it’s a hell of a lot easier than some of the hyperscalers’ other ideas, like building nonexistent nuclear fusion plants, or nonexistent small modular reactors, or restarting a long-shuttered nuclear reactor at the notorious Three Mile Island plant.

These dynamics led some of my fellow conference goers to muse about a counterfactual choice: Would you rather have strong federal policy tailwinds and an unfavorable market, or booming market fundamentals but unfavorable policy? Nine months ago, the industry enjoyed both. Trump ended those good times, but the robust market serves to mollify the pain of his policy attacks.

SEIA has strived to welcome energy storage into the fold, and diversification from solar alone looks especially prescient these days. Rooftop solar is struggling in a big way, with the federal onslaught and friendly fire from states like California, and large-scale developers are racing to cram in a bumper crop of projects before tax credits disappear next July. (Projects that start construction after that must be operating by the end of 2027 to qualify for the federal incentives.) But storage companies evaded the policy setbacks of their solar-powered brethren, and are building toward yet another record year of construction.

“Right now, we are seeing all of the factors are very supportive to storage,” said Johnson. “Demand is going up, there’s more of a focus on having dispatchable power. It got tax credits for the first time in the IRA … and then it retained the tax credits in [the One Big Beautiful Bill Act].”

The budget law preserves the battery-installation tax credits through 2033, with the stipulation that projects prove they don’t excessively rely on parts or corporate support from China. That sparked initial concerns from some analysts that these Foreign Entity of Concern rules (FEOC) could be enforced in a way that strangles development arbitrarily.

A few months later, many storage developers are encouraged by how clearly the text of the law lays out the boxes to check. Even so, compliance creates extra work for the American companies trying to expand the capacity of the grid, and the law does not explicitly encourage domestic manufacturing, since the rules are anti-China rather than pro-America.

Trump’s tariffs also pose a unique threat to storage, because so many of the battery cells used in these projects come from China. The U.S. has only just begun building supply chains for lithium ferrous phosphate, the battery chemistry now favored for grid storage. LG opened an LFP factory in Michigan this summer; AESC did so in an old Nissan Leaf battery plant in Tennessee, and Tesla is working on one in Nevada slated to start up early next year.

Now, said Brian Hayes, CEO of storage developer Key Capture Energy, it’s common for suppliers to offer three battery-sourcing options: China, Southeast Asia, and domestic. Buyers can toggle based on current tariff rates, U.S. manufacturing premiums, and the FEOC obligations of a particular project. Once the new FEOC rules kick in, though, the industry will need to move away from Chinese-made battery cells.

“I’m feeling a lot more positive today than I was six months ago,” said Hayes, whose company has built 40 megawatts in New York and 580 megawatts in Texas. “We ended up in a good place.”

That’s not to say storage developers can afford to get complacent.

“We can’t rest on our laurels,” Hayes mused. “We always have to be paying attention to what else could come.”

The Biden administration combined trade policy with methodical domestic incentives to reshore the manufacturing of clean energy equipment and other tech, like semiconductors. Trump supports the resurgence of domestic manufacturing in theory, but his primary tactic for that goal has been frequently shifting and legally dubious tariffs. These policies raise the price for materials that American manufacturers need to make their products and for the equipment required to build new factories, and they undermine the long-term certainty that reassures investors.

Still, the reshoring of clean energy supply chains has continued, and signs touting FEOC compliance have become a new form of currency on the expo hall floors.

Nextracker, the homegrown solar-tracking manufacturer and publicly traded cleantech success story, used the occasion of the conference to publicize its acquisition of Origami Solar for $53 million. That marked a refreshing shift in an era when cleantech acquisitions have tended to feature bankruptcy auctions or the kind of firesale where participants abashedly refuse to share the purchase price.

Origami developed a steel frame technology to replace the usual aluminum frames that wrap around solar panels. This enhances structural integrity as solar modules grow ever larger and more powerful. Indiana manufacturer Bila Solar, for instance, recently tapped Origami to frame its new 550-watt solar module.

But beyond preventing bending or buckling, the acquisition is a domestic-production play. The U.S. aluminium industry has cratered since the 1980s, so aluminum frames are now largely an import business, subject to all the vagaries of trade in 2025. The U.S. still makes things with steel though; Nextracker has been working with partners to open steel plants around the country to produce the torque tubes that carry the panels through their daily rotation. Origami manufactures in the U.S. too; now Nextracker can offer a more complete domestic solar package, making it easier for developers to clinch the 10% tax credit adder for Made-in-America content.

Over in Texas, module manufacturer T1 Energy signed a deal a few weeks back with glass producer Corning for a lot more than oven-safe casserole dishes. Corning subsidiary Hemlock Semiconductor will make hyper-pure polysilicon and carve it into solar wafers in Michigan, to supply T1’s forthcoming solar cell factory starting in the second half of 2026.

I tracked down Alex Zhu, CEO of ES Foundry, which in January opened one of the only currently operating solar cell factories in the country. Production from the 1-gigawatt line in Greenwood, South Carolina, is already sold out until 2027, Zhu said. He has greenlit a 2-gigawatt expansion, slated to be fully running by June 2026, to meet demand from domestic panel producers. A digital display by the company’s booth advertised “No FEOC Ownership. No FEOC Board. No FEOC Funding.”

Zhu stressed that it wasn’t easy opening a cell factory when the U.S. lacks a supply chain for some of the industrial inputs that are abundant and cheap in China. One of the key gases used in the process cost him 120 times the rate it sells for in that country’s solar industry centers. But Zhu nonetheless raised investment, launched the company, and built the factory all in the last two years.

Sales of these U.S.-made cells very much depend on the domestic content adder to compete with cheaper imports: “That’s the only drive to make the economic sense to buy a more expensive domestic module and domestic cell,” Zhu noted.

That’s a clear risk factor, because that perk will disappear along with the solar tax credits. But tax rules say that if developers start construction before next July 4, they can take up to four years to finish projects. That means projects could get built with both the credit and the domestic content adder through the end of the decade.

It’s hard to know what context manufacturers will be operating in at that point. But Zhu noted that “after five years, we definitely need to move to the next generation.” Much like semiconductor fabs, solar cell factories must regularly refresh themselves to keep up with technological advancements.

Longer-term certainty would be nice for the generational effort to reshore the solar supply chain, but maybe five busy years of manufacturing is enough to look forward to right now.

Maryland’s first offshore wind farm could have broken ground next year. But now the 114-turbine renewable energy project is all but doomed following the Trump administration’s most recent move in a long line of attacks on the industry.

In a motion filed Friday with the U.S. District Court in Maryland, the Interior Department asked a judge to cancel approval of the Maryland Offshore Wind Project, which was authorized in the final weeks of the Biden administration. The wind farm was expected to power over 718,000 homes in a Democrat-led state facing rocketing energy demands.

Officials claim that the agency’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management made an “error” when assessing the turbines’ potential impact on other activities — like search-and-rescue operations and fishing — within the 80,000-acre swath of ocean where the wind farm would be located.

The project is over a decade in the making, with developer US Wind purchasing the lease in 2014. But after President Donald Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act in July and greatly shortened the duration of the wind energy tax credit, Maryland’s first offshore wind farm already seemed impossible to pull off — at least economically.

Harrison Sholler, an offshore wind analyst with BloombergNEF, told Canary Media in July that with the tax credits sunsetting at a much earlier date, the Maryland project would likely no longer be able to offset 30% of its costs. The original rule for receiving the incentives required construction to start by 2033 or potentially even later, but the new law stipulates that wind farms must be “placed in service” by the end of 2027 or begin construction by July 4, 2026, to qualify.

Onshore construction is not supposed to start until next year at the earliest, and at-sea installation not until 2028, so the new deadline for receiving tax credits was crushing. Also, US Wind doesn’t have its financing in place yet to underwrite construction, according to Sholler. Securing financing without those credits guaranteed is a hard sell.

Analysts saw the tightening of the tax credit’s timeframe down to this one-year sprint as the final nail in the coffin for offshore wind farms that were fully approved but not currently underway.

Two projects — MarWin, the first phase of the Maryland Offshore Wind Project, and New England Wind off the Massachusetts coastline — exist in that gray zone. If the judge yanks its approval, MarWin will almost certainly be mothballed for the rest of Trump’s tenure.

Four offshore wind farms are currently being built in America’s waters. A fifth project, Revolution Wind, is 80% complete, but Interior Secretary Doug Burgum abruptly paused its construction in August, citing “national security” concerns. Project developer Ørsted is challenging the federal freeze in court. That saga is part of an escalating war on wind power led by the White House that has thrown the industry into chaos in recent weeks.

US Wind is a joint venture of the Italian corporate giant Toto Holding and Apollo Global Management, an investment firm. A spokesperson for the company said it will fight to maintain its approvals.

“After many years of analysis, several federal agencies issued final permits to the project,” spokesperson Nancy Sopko said in a public statement released Friday. “We intend to vigorously defend those permits in federal court, and we are confident that the court will uphold their validity and prevent any adverse action against them.”

This article was copublished with The Daily Yonder, a newsroom covering rural America.

YARMOUTH, Maine — At a dock along the banks of the Cousins River, Chad Strater loaded up his small aluminum workboat with power tools and a winch. Strater, who owns a marine construction business, was setting out to tinker with floating equipment at a nearby oyster farm. On the quiet morning in August, with the sun already beating down hard, his vessel whirred to life, only without the usual growl of an oil-guzzling motor. The boat is all electric.

Just north of where the Cousins River meets Casco Bay, Willy Leathers was powering up his own electric watercraft, which had its first outing in July. Leathers uses his 28-foot boat for cultivating oysters at Maine Ocean Farms, where roughly 3 million of the animals grow in dozens of floating cages.

Both Strater and Leathers said they switched to electric workboats for several reasons. Their new watercraft are a cleaner alternative to the smelly, polluting petroleum-powered vessels that dominate Maine’s 3,500 miles of coastline. Electric propulsion is also significantly quieter than a gas or diesel motor. For Leathers, whose 10-acre sea farm is a significant presence in the cove where he operates, the swap is about being a good neighbor to the shoreside community.

“It’s an innovation born from necessity for us,” said Strater about his electric boat, which he docks each night at the Sea Meadow Marine Foundation, the nonprofit boatyard and aquaculture innovation hub he runs with several other small business owners. “[The boat] really works well for what we do with it, and we’re letting farmers use it to see how it could work for them.”

Battery-powered vessels are starting to catch on in the United States and worldwide as companies and maritime authorities work to reduce emissions and improve the experience of cruising waterways. The technology ranges from small outboard motors on workboats and recreational watercraft to powerful inboard systems on ferries, tugboats, and supply vessels for offshore wind farms and oil rigs.

In recent decades, Norway, with its extensive coastline and ample government funding, has spearheaded the transition globally. China, which is both the world’s largest shipbuilder and battery manufacturer, has rapidly deployed hundreds of battery-powered vessels over the last several years. Falling battery costs, better technology, and stricter environmental rules are compelling some vessel owners to install partial or fully electric systems, primarily for watercraft that operate near the shore or on fixed routes. For commercial fishing in particular, customers are helping to drive the push to clean up.

“Everyone’s more concerned now with where their food comes from, and we’ve seen that [consumers] are looking for that complete sustainable supply chain,” said Ed Schwarz, the head of marine solutions sales in North America for Siemens Energy, which has built electric propulsion systems for U.S. ferries.

Electrification has only very recently come to America’s aquaculture sector. In Maine, the small but fast-growing segment includes nearly 200 farms for shellfish, fin fish, and edible seaweed. Strater and Leathers are among the first in their business to trade gas motors for electric propulsion — a switch they say they’re hoping to accelerate. Oil-guzzling motors are among the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions for the state’s multibillion-dollar seafood sector.

Still, electrifying commercial watercraft can be a difficult course to navigate, given the higher up-front costs of electric motors and the lack of charging infrastructure — and grid infrastructure in general — in rural waterfront communities.

Early adopters like Strater and Leathers said they hope the experiences gained from their demonstrations can help pave the way for decarbonizing Maine’s blue economy. With the help of the Island Institute, a Maine-based nonprofit that works on marine-related energy transitions, Leathers is collecting performance data from his vessel to share more broadly with the industry.

“People say it looks cool and shiny and looks like it operates great,” Lia Morris, the Island Institute’s senior community development officer, said of electric boats. “But we really want to be able to prove out the [business] case.”

Electric boats can cost between 20% and 30% more than a gas- or diesel-powered vessel of a comparable size. However, owners can save on maintenance and fuel over the long term, Strater’s business partner Nick Planson said.

“The high-level math that we’ve come up with” is a financial break-even point of “about four to five years, and then over a 10-year time span, you’re definitely coming out way ahead based on the vastly reduced maintenance cost, replacement cost of failed equipment, and fuel costs,” said Planson.

But the initial price tag presents a significant hurdle. Strater and Planson’s sleekly designed, no-frills watercraft cost $100,000 to build and outfit with a single electric outboard motor. Leathers’ boat, called Heron, cost about four times more. It has two electric outboards and a ramp for unloading and hauling more than 10,000 oysters at a time from the sea farm to distributors waiting on the dock. Its hull is also equipped with a small cabin and toilet.

Both operations relied on grant funding to defray the expense of going electric.

For their part, Strater and Planson used about $50,000 from a larger U.S. Department of Agriculture small business grant they got in 2024 to establish a use case for electric workboats in the aquaculture industry. Leathers’ business, Maine Ocean Farms, was included on a collaborative $500,000 U.S. Department of Energy grant last year that earmarked about $289,000 for boat building and propulsion systems, in addition to other funds for charging infrastructure and data collection.

The prospects for funding future projects are now much murkier under the Trump administration, maritime policy experts say.

The DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, which awarded the money to Maine Ocean Farms and its partners, is facing significant budget cuts in the next fiscal year. The GOP-backed spending law that passed in July rescinded some unobligated grant funding for cleaning up marine diesel engines. While other programs were spared, it’s unclear whether the current Congress will approve new funding for initiatives ranging from electrifying huge urban ports to deploying low-emissions ferries in rural communities.

But federal grants aren’t the only way to address the higher cost of electric boats. Strater and Planson also worked with Coastal Enterprises Inc., a Maine-based community development financial institution focused on climate resilience, to establish a “marine green” loan program that can make the up-front costs of switching to electric propulsion more accessible to small businesses.

“The more electric engines that are being employed in Maine helps lift the whole tide for everyone,” said Nick Branchina, director of CEI’s fisheries and aquaculture program. As part of its marine green lending, CEI offers loans starting at $25,000 for small businesses to make the switch to electric propulsion and comfortably afford the cost of batteries or a shoreside charging installation.

Planson said that as electrification moves beyond initial grant-funded projects, the challenge is keeping systems affordable. He said he wants to see other small business owners able to “take a reasonable swing” at electric propulsion.

Buying a boat, of course, is only the first obstacle. Electric vessel owners must also learn how to use their new propulsion systems and find a place to charge them.

This summer, Leathers said he’s had no trouble making the nearly two-mile round trip from the slip where he docks Heron in South Freeport, Maine, to his farm on Casco Bay. With a full charge, he can make trips slightly farther to meet distributors closer to Portland. But as temperatures drop this winter, Leathers said he’s not sure how far the outboards’ two batteries will take him. Cold weather can reduce battery capacity and impact performance, shrinking an electric motor’s range. It’s a part of Leathers’ demonstration to find out what the impacts are in practice.

Like Leathers, Strater and Planson also work year-round. They said they’re both impressed with how their boat performed last winter after launching in the fall of 2024. For Planson, who markets battery-powered equipment to aquaculture farmers as part of his startup, Shred Electric, a boat’s ability to run through the year’s coldest months is a key selling point.

“The proof is in the pudding,” said Planson. “When you’re working with … waterfront applications, it really needs to work every day and all year.”

Strater and Planson said their boat’s range was an important consideration when they partnered with the startup Flux Marine to build the electric outboard motor. With limited shoreside charging infrastructure in place, the boat has to make it out and back on a single charge, sometimes to aquaculture operations seven miles away. In the 10 months since the boat’s launch, Strater has learned range correlates to speed. He can modulate the boat’s pace depending on how far he wants to go.

“We can go really fast for a short distance. We can go really slow for a long distance, and it works for what we do with it,” he said.

Soon, Maine’s early adopters will have shared access to a higher-capacity Level 2 charger that will be installed at the Sea Meadow Marine Foundation and can charge batteries in little over two hours, or three times faster than the current system. The startup Aqua superPower was awarded a portion of the DOE funding last year to install additional marine chargers there and at a wharf in Portland owned by the Gulf of Maine Research Institute. Island Institute also helped with grant funding for the charger at the Sea Meadow boatyard.

Maine will need much more high-capacity charging infrastructure for the marine industry to transition to electric propulsion, said the Island Institute’s Morris. As the state’s aquaculture and fisheries industries look to grow beyond small-scale operations, other businesses will need to charge more frequently to make longer, farther trips up and down the coast.

Expanding charging stations north of Casco Bay represents what Morris calls a “chicken and egg” problem: a dynamic where chargers are either installed before demand gets high, and sit unused, or electric boats hit the water and there’s not enough charging infrastructure, stalling future adoption.

This challenge is compounded by both New England’s aging grid infrastructure and the remote nature of some of the region’s waterfront access points. Getting the right amount of power to a charging station on the shore can be costly, even in Yarmouth, which sits on Casco Bay. Often it’s the last mile that can be the most expensive. At Sea Meadow Marine Foundation, three-phase power, which can accommodate higher loads, is limited by the dirt road that separates the boat launch from the more heavily trafficked U.S. Route 1.

“There are a lot of complicated questions,” Morris said. “I don’t think it’s unique to Maine, it’s any rural area, but complicated questions and conversations with the utilities and the rural municipalities are going to have to be solved for.”

Back on the water, Leathers docked his electric boat, Heron, alongside the sea farm’s barge, where thousands of oysters pass through for processing on harvest days. He switched the motor off and hopped onto the floating platform. For a moment, the bay was calm to the point of near silence. Then Leathers picked up an oyster cage with a rattle, turning it over in his hands as water splashed out. The sounds of the workday began.

“As a whole industry, I think it’s going to take proving that someone like us can do it,” Leathers said. “And then the next person kind of snowballing after that.”

The first passenger terminal for air travel in the U.S. was an Art Deco celebration of aviation. In 1935, the fearless Amelia Earhart dedicated the building at the busy airport now known as Newark Liberty International, and within a few years, hundreds of thousands of passengers were hurrying through its marble-and-terrazzo lobby to catch commercial flights.

Now an administrative center called Building One, the former terminal has made history for a new reason: It’s the first edifice owned by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, a bistate transportation agency, to undergo an all-electric retrofit.

“It’s so exciting to see [this kind of] reinvestment and making things new again,” said James Lindberg, senior policy director at the nonprofit National Trust for Historic Preservation, who wasn’t involved in the project. “Energy efficiency and decarbonization is part of that. … We know how to do it — we just need more of it.”

Buildings account for a whopping one-third of the nation’s carbon pollution. Every building — even the 80,000 structures that, like Building One, are listed in the National Register of Historic Places — must break up with fossil fuels to align with a cooler climate future.

Retrofitting any existing structure is going to be tougher than going with all-electric systems from the start. But engineers looking to upgrade historic buildings are doubly constrained by the need to maintain their charges’ distinctive architectural features; you can’t just tear down the walls of a landmark.

The Port Authority’s Building One is an early example demonstrating that storied buildings can be electrified — all while keeping their vaunted status intact.

It “was the perfect project to show the art of what’s possible,” said Dennis Pietrocola, director of operations services at the Port Authority. “If we were able to undergo an electrification transformation to Building One” — among the most challenging of the Port Authority’s structures — “then it sets the stage for [decarbonizing] the rest.”

That’s coming. The Port Authority aims to be carbon neutral by 2050, a goal that includes its entire portfolio of more than 1,000 buildings — from storage and parking structures to terminals to offices — at its airports, bridges, tunnels, railways, bus stops, and shipping ports.

Building One is the bustling home base of 190 Port Authority employees, including operations and maintenance workers, police, and firefighters. In 2023, the building’s gas-fueled equipment was ready to conk out, making it a prime candidate for a decarbonization retrofit. Pietrocola and his colleagues carefully planned a series of cost-effective electrifying updates and hired an experienced general contractor, Constellation NewEnergy, to carry them out.

The team installed five large heat pumps on the roof to provide zero-emissions heating and cooling. They put in an energy-recovery system to recycle waste heat from the locker and IT rooms. The crew added a system that can dial down power use when the grid is strained by high demand. And in the parking lot, workers installed 29 new charging ports for electric vehicles.

The team also swapped the building’s gas boilers with electric-resistance ones. Operating with the same physics as big electric tea kettles, these provide an extra boost as needed to the building’s water-based heating system. Pietrocola had considered using heat-pump boilers instead, which can be twice as efficient because they move heat instead of making it, but he nixed the idea because it would’ve meant replacing the hydronic system’s distribution pipes with bigger ones.

Workers also made some more staid updates to lower energy costs: weatherizing the building, applying heat-blocking films on the windows, and replacing more than 1,500 light fixtures with ultra-efficient LEDs.

In total, the project took 18 months and cost about $15 million — $3 million more than it would’ve had the Port Authority stuck with gas-fired equipment, according to Pietrocola.

The Port Authority didn’t use any incentives to cover the expenses, in part because the team needed to act quickly to replace the building’s worn-out systems. But federal and state tax credits are available to private entities and public-private partnerships to electrify operations as part of renovation projects, Lindberg pointed out. Unlike the consumer credits for heat pumps, EVs, and other clean energy tech, the Rehabilitation Credit was left unscathed by Republicans’ federal budget law enacted this summer, he said.

Building One’s retrofit has slashed energy use by about 25%, Pietrocola said. Still, due to the area’s relatively high cost of electricity, he doesn’t expect the structure’s utility bills to fall.

Pietrocola plans to apply the lessons learned at Building One to other Port Authority structures as their fossil-fueled systems age out, he said. He’ll approach each project with a fresh eye to the building’s particular needs and the technology available. Next time, he added, the agency may go with hydronic heat pumps instead of the electric-resistance boilers.

Decarbonizing buildings “is a very important cause to me, personally and professionally,” Pietrocola noted. Recently, he worked with his 14-year-old daughter, Kayla, on a climate-change science project. “It made me realize, well, I’m part of the problem — the way I’ve operated facilities [in the past], perhaps with a closed mind.” After guiding the electrification of one of the country’s most storied structures, he feels like he’s become part of the solution.

The article was originally published by Earthobservatory.nasa.gov

August 21, 2025

September 6, 2025

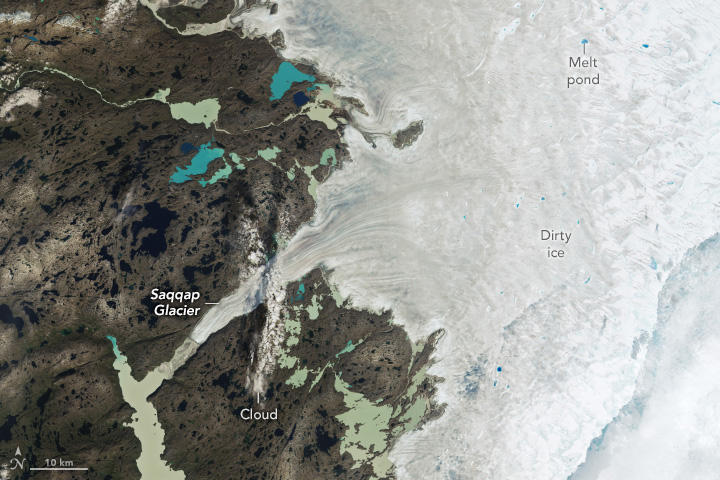

Ice covers about 1.7 million square kilometers (656,000 square miles) of Greenland, forming the largest ice sheet on Earth outside of Antarctica. Each summer, its surface begins to melt under the warmth of the Sun, intensified by the season’s long daylight hours and sometimes further enhanced by clouds and rain.

Greenland’s melting season usually runs from May to early September. The 2025 season was considered “moderately intense,” ranking 19th in the 47-year satellite record for cumulative daily melt area as of late August, according to an analysis by the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). This year’s season featured an extended period of melting in part of July and a sharp increase in warmth and melting in mid-August.

The mid-August spike, which was preceded by significant rainfall in some areas, peaked on August 21, when melting was observed across nearly 35 percent of the ice sheet—a record for that date, according to the NSIDC. These satellite images show the ice sheet on that day (left) and nearly two weeks later (right), along part of its southwestern edge about 150 kilometers (90 miles) northeast of the capital city of Nuuk (not shown). Both images were captured by the OLI-2 (Operational Land Imager-2) on Landsat 9.

In the August image, a vast expanse of gray, “dirty” ice is visible. The darker appearance is due to particles like black carbon and dust that have accumulated on the ice sheet. As the snow and ice melt, these impurities are left behind, making the ice appear even darker. This darkening reduces the ice’s albedo—its ability to reflect sunlight—causing it to absorb more solar energy and melt even faster during the summer months. Several ponds of light- and deep-blue meltwater dot the ice, and scattered clouds cover part of the ice sheet in the middle and bottom-right of the scene.

By the date of the September image, a fresh layer of snow appears to cover much of the dirty ice as well as some of the land. While major melt events have occurred as late as September in previous years, they become less likely this time of year as temperatures typically drop with the Arctic’s diminishing daylight.

Scientists track seasonal melting each year because it is one of the ways the massive Greenland Ice Sheet loses ice. (Iceberg calving and melting at the base of tidewater glaciers also play a role.) As air and water temperatures have risen in recent decades, ice losses have outpaced ice gains, contributing to sea level rise.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kathryn Hansen.

Every day, people are invited to buy products and services with supposed climate benefits – whether this be “carbon-neutral flights”, “net-zero beef” or “carbon-negative coffee”.

Such claims rely on “carbon offsets”.

Put simply, carbon offsets involve an entity that emits greenhouse gases into the atmosphere paying for another entity to pollute less.

For example, an airline in a developed country that wants to claim it is reducing its emissions can pay for a patch of rainforest to be protected in the Amazon. This – in theory – “cancels out” some of the airline’s pollution.

It is not just businesses that are relying on carbon offsets. Major economies, too, are investing in carbon offsets as a way to meet their international emissions targets – with offsetting becoming a major talking point at UN climate negotiations.

For its supporters, offsetting is a mutually beneficial system that funnels billions of dollars into emissions-cutting projects in developing countries, such as renewable energy projects or clean cooking initiatives.

But offsetting has also faced intense scrutiny from researchers, the media and – increasingly – law courts, with businesses facing accusations of “greenwashing” over their carbon-offsetting claims.

There is mounting evidence that offset projects, from clean-cooking initiatives to forest protection schemes, have been overstating their ability to cut emissions. One yet-to-be published study suggests that just 12% of offsets being sold result in “real emissions reductions”.

Projects have also been linked to Indigenous people being forced from their land and other human rights abuses.

Decades of countries trading carbon offsets has had a negligible impact on emissions and likely even increased them.

In this in-depth Q&A, Carbon Brief explains what offsets are, how they are being used by businesses and nations, and why they can be a problematic climate solution. The article also explores whether a system, which one expert describes as “deeply broken”, could ever be effectively reformed.

Carbon offsetting allows individuals, businesses or governments to compensate for their emissions, by supporting projects that reduce emissions elsewhere.

In theory, after cutting their emissions as much as possible, offsets can pay for low-carbon technologies or forest restoration to “cancel out” emissions they cannot avoid.

This could also provide support for relatively low-cost climate action in developing countries and facilitate greater global ambition.

But, in practice, offsetting often enables these entities to justify “business as usual” – producing the same volume of emissions while making claims of reductions that rely on offsets.

Carbon offsets are tokens representing greenhouse gases “avoided”, “reduced” or “removed” that can be traded between an entity that continues to emit and an entity that reduces its own emissions or removes carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere.

While it allows the first group to continue to emit, theoretically, the second must reduce its emissions or sequester CO2 by an equivalent amount.

Offsets are usually calculated as a tonne of CO2-equivalent (tCO2e) and are also described as tradable “rights” or certificates.

The terms “carbon offsets” and “carbon credits” are often used interchangeably, but the key difference lies in the marketplace they are traded in and how they are mandated to deliver on emissions reductions.

There are broadly two types of carbon markets on which offsets can be traded. The first is the “compliance” market, which is regulated and involves emissions reductions that are mandated by law, supported by common standards and count towards national or sub-national targets.

Common examples include cap-and-trade emissions trading schemes, such as the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), where power plants and factories must submit carbon “allowances” to cover their emissions each year, within an overall “cap” for regulated sectors.

Companies can buy and sell allowances from – and to – each other. In some cases they can also buy approved offsets from external emission-cutting projects to stay within their limits.

Such schemes cover around 18% of global emissions and, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), they have contributed to emissions cuts in the EU, US and China.

Nevertheless, there is considerable evidence that many of the external offsets that have fed into these schemes have resulted in negligible emissions cuts. (See: How are countries using carbon offsets to meet their climate targets?)

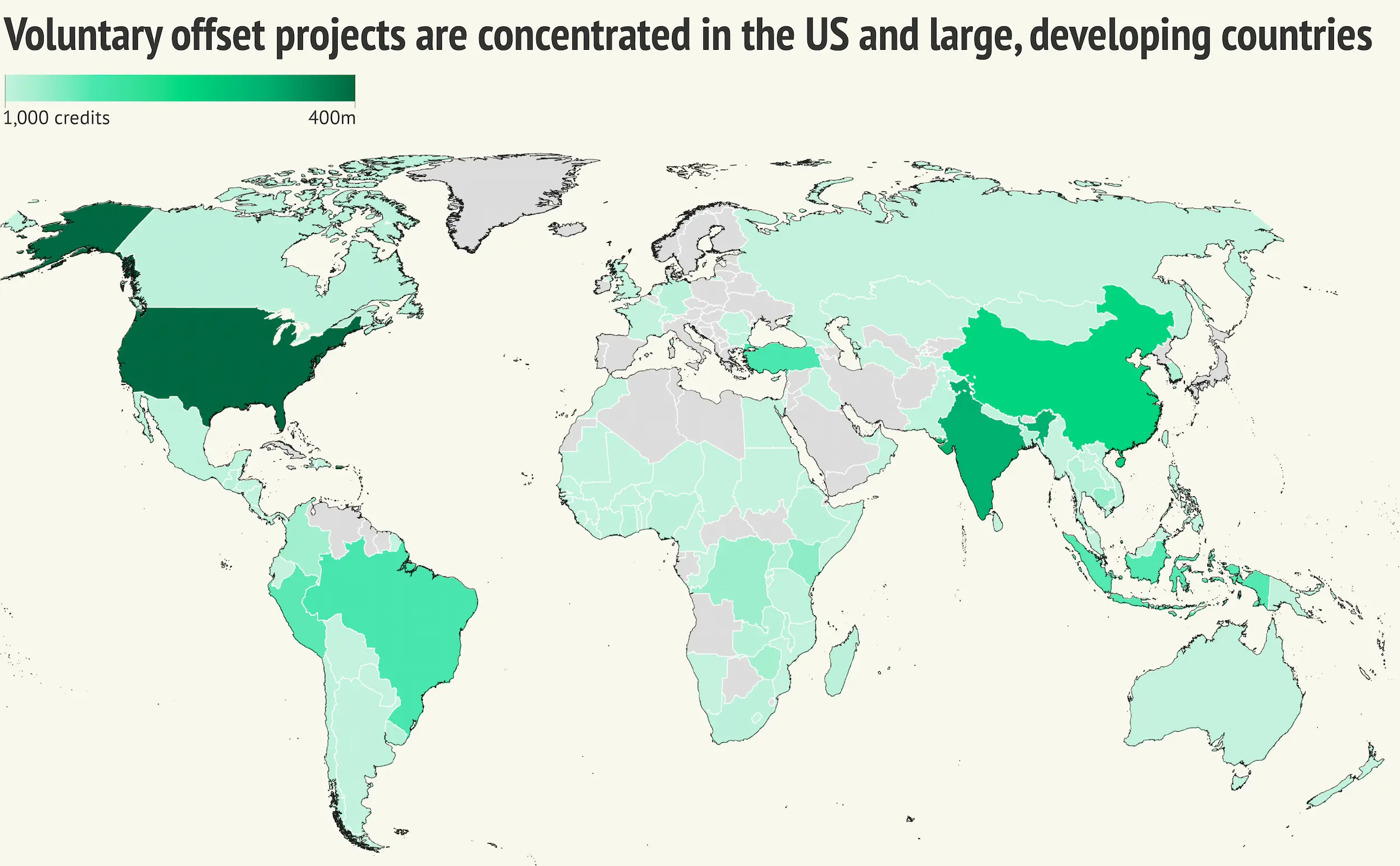

The second type of carbon market is the largely unregulated voluntary carbon market, where offsets are used by corporations, individuals and organisations that are under no legal obligation to make emission cuts. Here, there is far less oversight and even less evidence of real-world emissions reductions.

(Most available credits are eligible for use on the voluntary market, but only a smaller subset can be used for compliance. Initially, UN and government-backed programmes were for compliance markets and NGO-backed programmes were for the voluntary market, but both types of programme now often cater to both markets.)

The table below shows a sample of offsetting registries and programmes on offer. These bodies “issue” offsets – meaning they confirm that a number of tonnes of CO2 has been cut, avoided or removed by a project.

These credits are then bought and “retired” when an entity wishes to count them towards its voluntary goal or binding emissions target. Once retired, they cannot be used again.

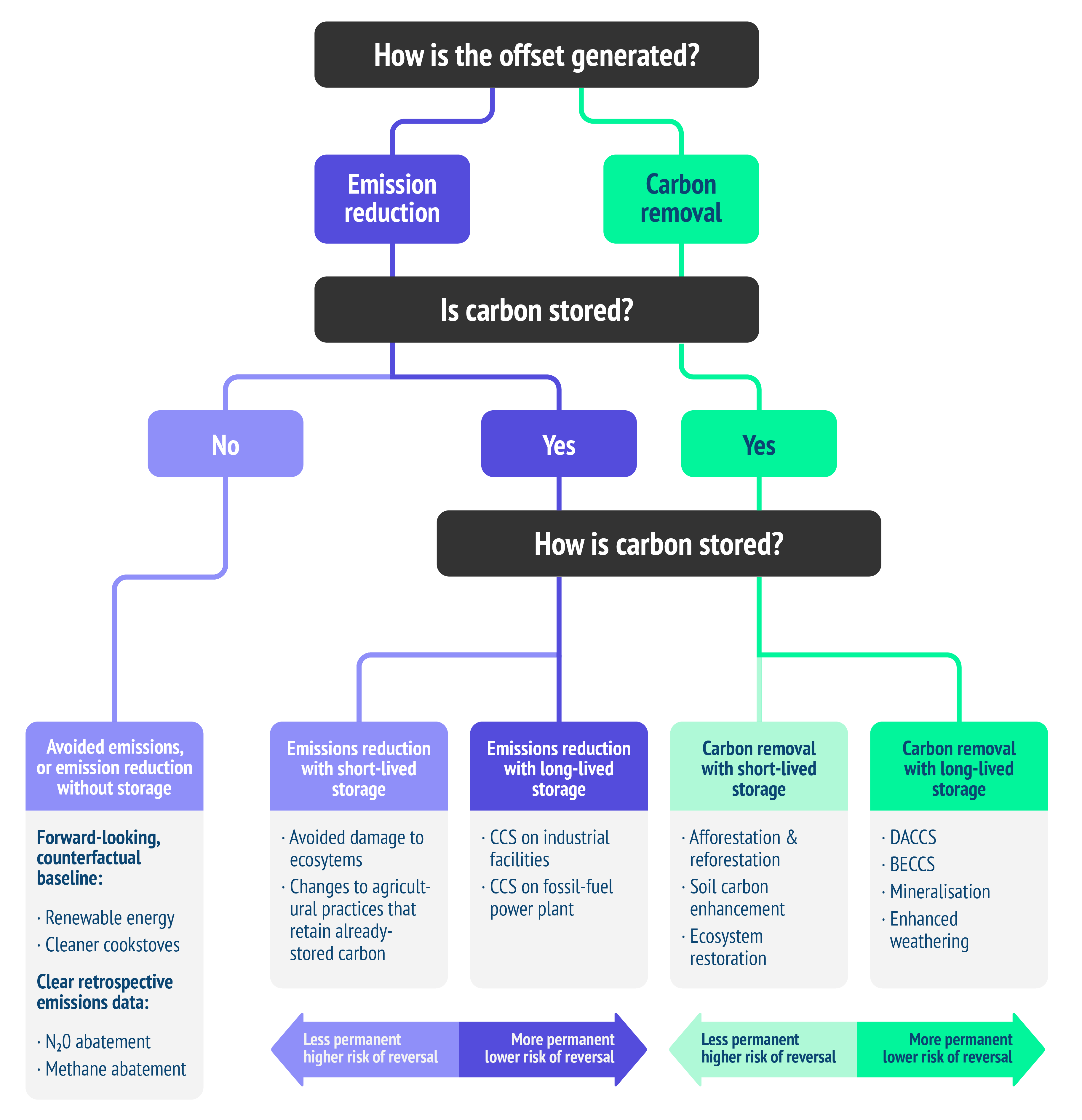

Offsets can broadly be sorted into two groups, which can be seen in the flow chart below, based on the work of the Oxford Offsetting Principles – an academic framework that seeks to define “best practice” for offsetting.

The first group covers “emissions reductions”. These offsets are used when an entity attempts to compensate for an increase in emissions in one area by decreasing emissions in another area. This group of offsets spans a few types, depending on whether emissions are avoided or reduced, with or without storage.

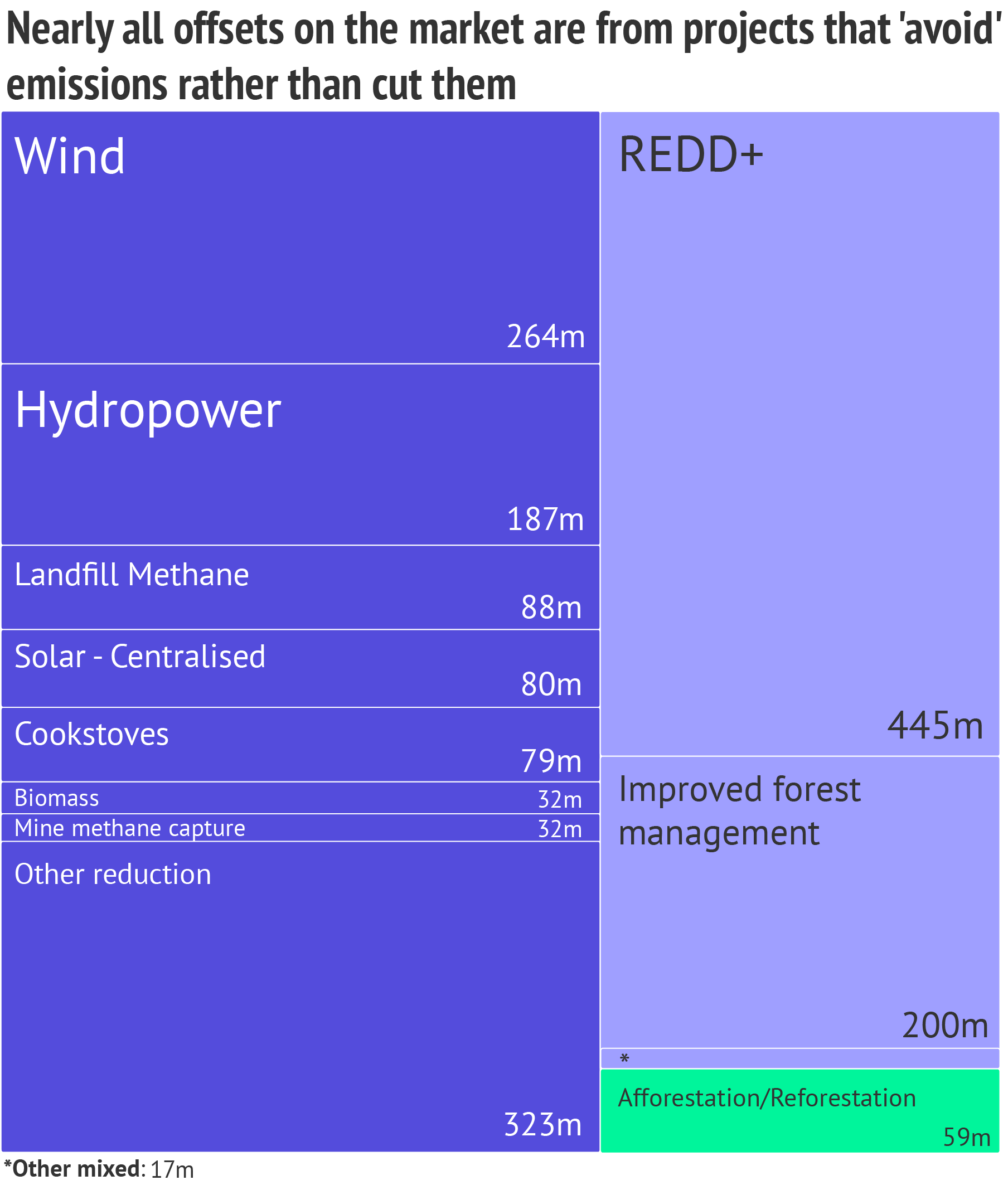

“Avoidance” or “avoided emissions” offsets are from projects that represent emissions reductions compared to a hypothetical alternative. One of the main types of avoidance offsets is renewable projects that are built instead of fossil-fuel plants. Another is “clean” cookstove schemes, where the distribution of more efficient cooking equipment is intended to cut reliance on traditional fuels, such as firewood, leading to lower emissions.

(Note that carbon offsets are a minefield of overlapping terminology and definitions. Here, “avoided emissions” offsets, as defined by the Oxford Offsetting Principles, are distinct from “emissions avoidance” credits, which have a distinct meaning within UN climate talks.)

Emission reduction offsets with short-lived storage of the relevant CO2 include credits from avoided deforestation projects, such as under the framework for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+). These are projects that aim to avoid emissions by protecting forests that would have otherwise been cleared or degraded.

(REDD+ was developed at the UN in the late 2000s as a way to help developing countries preserve their forests and is part of the Paris Agreement on climate change. Separately, projects labelled as REDD+ – which may not be aligned with UN rules – have emerged as a major part of the voluntary offset market, accounting for around a quarter of total volumes.)

Adding carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology to a fossil-fuel power plant, meanwhile, could generate emission reduction credits with a longer shelf-life.

“Removals” offsets are generated by projects that absorb CO2 from the atmosphere. Today, most removal offsets involve tree-planting projects, which do not guarantee permanent storage. (See: Could carbon-offset projects be put at risk by climate change?)

A new wave of more permanent removal offsets could be generated using machines that suck CO2 out of the air and techniques such as enhanced rock weathering. So far, these offsets are limited to the voluntary market and are still under review for inclusion in a new international “Article 6” carbon market by the UN.

Taxonomy of carbon offsets with five types of offset based on whether carbon is stored, and the nature of that storage. Diagram by Carbon Brief, based on the original by Eli Mitchell-Larson for the Oxford Offsetting Principle.

According to Carbon Brief analysis of data from the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, just 3% of offsets on the four largest voluntary offset registries involve removing CO2 – all from tree-planting projects.

Many available offsets have been labelled “junk” or “hot air” because they result from carbon-market design flaws and do not represent real emissions reductions.

The ideas and experiments with carbon offsets and trading trace back at least half a century, as outlined in the timeline below.

Over the years, offset projects have been dogged by allegations of land conflicts, human rights abuses, hampering conservation and furthering coal use and pollution.

They have been decried as a “false solution” by activists. Negotiations over new carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement have seen a sustained outcry for not delivering mitigation at scale, threatening Indigenous rights and “carbon colonialism”.

Meanwhile, companies claiming carbon neutrality using voluntary offsets have been increasingly called out and restrained from making “greenwashing” claims. (See: Why is there a risk of greenwashing with carbon offsets?)

The central problem of carbon offsetting is summarised by Robert Mendelsohn, a forest policy and economics professor at Yale School of the Environment. Reflecting on the achievements of carbon offsets, he tells Carbon Brief:

“They have not changed behaviour and so they have not led to any reduction of carbon in the atmosphere…They have achieved zero mitigation.”

Yet with carbon offsets now firmly established, there are still many who view them as an effective way to bolster corporate climate action, encourage governments to pledge more ambitious emissions cuts and channel climate finance where it is most needed.

“I think we can solve the problems that we currently have in the carbon-market space,” Bogolo Kenewendo, a member of the steering committee for the Africa Carbon Markets Initiative, tells Carbon Brief, emphasising the need for “high quality and high integrity credits”.

Since its formation in 1988, the UN’s climate science authority, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), has published six sets of “assessment reports”. These documents summarise the latest scientific evidence about human-caused climate change and are considered the most authoritative reports on the subject.

Prof Joeri Rogelj – director of research at the Grantham Institute – Climate Change and the Environment and professor in climate science and policy at the Centre for Environmental Policy at Imperial College London – has been involved in writing several of these reports.

He tells Carbon Brief that the phrase “carbon offsets” is “not part of the jargon that the [scientific] literature uses”, so it is not widely used in IPCC reports either.

Most carbon-offset projects around today involve “emissions reductions”, whereby an entity can compensate for their pollution by paying for emissions to not happen somewhere else.

This is most commonly achieved by entities supporting, say, the creation of new renewable energy projects in the place of fossil-fuel schemes, for projects that supply clean cookstoves in the global south or for projects that protect ecosystems in order to avoid more deforestation. (More on this in: What are ‘carbon offsets’?)

While IPCC reports do not say much on carbon offsets, they do discuss the role that these kinds of techniques could play in helping the world meet its climate goals.

For example, the latest IPCC report on how to tackle climate change says that all scenarios for limiting global warming to either 1.5C or 2C involve “greatly reduced” fossil fuel use and a transition to low-carbon sources of energy, such as renewables.

It also says that changes to land-use, such as stopping deforestation, “can deliver large-scale greenhouse gas emissions reductions” – although it adds that this “cannot fully compensate for delayed action in other sectors”.

The report also notes that all scenarios for keeping global warming at 1.5C or 2C require “widespread” access to clean cooking.

A much smaller proportion of carbon offsets around today work by aiming to remove CO2 from the atmosphere to compensate for an entity’s emissions elsewhere.

This is commonly achieved by planting trees, which remove CO2 from the atmosphere as they grow, or by restoring damaged ecosystems, which are natural carbon stores.

Other, more technologically advanced types of CO2 removal are being tested and developed by a handful of companies around the world.

These include growing plants, burning them to generate energy and then capturing the resulting CO2 emissions before they reach the atmosphere – a technique called bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS).

Another proposed technique would be to use giant fans to suck CO2 straight from the atmosphere before burying it underground or under the sea – a technology called direct air capture and storage (DACCS).

However, neither one of these technologies exist at scale at present – and, therefore, do not yet play a large role in carbon offsetting.

The latest IPCC report on how to tackle climate change concludes that CO2 removal techniques are now “unavoidable” if the world is to limit global warming to 1.5C or 2C.

And Carbon Brief analysis finds that CO2 removal is used to some extent in nearly all scenarios that limit warming to below 2C.