Clean energy is starting to bend the curve on China’s fossil-fuel use.

Overall, carbon-free sources met more than 80% of China’s new electricity demand last year — a marked difference from recent years. Between 2011 and 2020, they met less than half of new demand, according to a new report from think tank Ember.

Thanks to China’s astonishingly fast rollout of carbon-free electricity, the country saw its fossil-fueled power generation fall by 2% in the first half of this year compared to the first six months of 2024. That’s a crucial metric to watch: China is the world’s largest source of planet-warming carbon emissions, and its electricity production generates more carbon dioxide than any other sector.

So far this year, the country has deployed 256 gigawatts of new solar capacity — double the amount it installed during the same period last year and orders of magnitude more than installed by the runner-up nations, India and the U.S. Earlier this year, China’s total solar and wind power capacity surpassed its coal-fired power capacity. In 2024, China installed more grid batteries than the U.S. and Europe combined. And the country is home to nearly half of the nuclear power plants currently under construction.

China’s overall fossil-fuel use could be about to decline, too. That’s because the nation is rapidly electrifying its economy — retooling more and more fuel-burning sectors, like transportation and heavy industry, to be powered by electrons instead of combustion. Electricity accounted for nearly one-third of the country’s final energy consumption in 2023, compared to less than a quarter for the U.S. and major European nations.

It’s yet more evidence that China is all in on becoming an “electrostate.” Meanwhile, under President Donald Trump, the U.S. has lost its momentum in abandoning fossil fuels. Greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. are still expected to fall under Trump, but more slowly than had been expected under Biden-era policies, as the federal government chooses to embrace fossil-fuel nostalgia over a clean-energy future.

There’s nothing like a shared frustration to bring people together. For a group of Mid-Atlantic and Midwestern states, that’s rising power prices on the grid operated by PJM Interconnection. Both Republican and Democratic governors are calling out PJM’s management and demanding change — a repeat of a cycle that’s been going on for years and has no easy solution.

The U.S. is home to seven regional transmission organizations and independent system operators that are each responsible for managing power transmission and operating energy markets among utilities in their area. PJM is the largest, serving more than 65 million customers across D.C., Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and 10 other states. And for years, leaders in those states have said it’s not doing a great job.

The crux of the issue is rising electricity prices. This summer, PJM announced a new record in its annual capacity auction, which it uses to secure power resources for the grid. Prices hit $16.1 billion, up from $2.2 billion in 2023, Canary Media’s Jeff St. John reported in July.

There are a few reasons for the spike in costs. For one, PJM expects that it will need a ton more power-generation capacity in the coming years as data centers come online — though experts dispute just how big the AI energy-demand bubble will actually be. PJM does have a massive backlog of clean-power and battery projects looking to connect to the grid and meet that demand. But the operator hasn’t undertaken reforms that critics say could speed interconnections, and is instead campaigning to keep expensive, dirty fossil-fuel power plants online.

PJM member states’ longstanding dispute with the grid operator reemerged this week as 11 of their governors met in Philadelphia. There, Pennsylvania’s Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro and Virginia’s Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin both said they would leave PJM if states don’t get a bigger role in the grid operator’s governance.

“This is a crisis of not having enough power, and it is a crisis in confidence,” Youngkin said. “It’s this crisis that demands real reform, real reform immediately — and at the top of the list is that states must have a real say.”

PJM President and CEO Manu Asthana acknowledged that his organization needs to take cost-cutting steps like improving its load forecasting and interconnection processes, but he also put the onus on states to better their own infrastructure siting and permitting rules.

Washington Analysis researcher Rob Rains is doubtful that states will follow through and depart PJM. He said doing so could actually cost customers more in the short term, as the states may have to negotiate their own power procurement at rates even higher than what PJM has secured. Rains predicts that instead of cutting ties with the grid operator, governors will pull other levers to pressure PJM to establish stronger power-market safeguards to keep prices low. Meanwhile, analysts at ClearView Energy Partners suggest states should keep up their push to get more electricity generation developed as soon as possible.

Trump stands alone at the U.N. climate summit

The U.S. set itself apart from the rest of the world at the United Nations’ climate summit this week, and not in a good way. On Wednesday, around 120 countries announced new emissions-reduction plans and climate commitments. That included China, the world’s top carbon polluter, which declared it would aim to cut emissions at least 7% from its peak by 2035. New pledges also came from other major emitters, including the European Union, and from countries with smaller populations and lower gross domestic product.

But the U.S. wasn’t among them. Instead, in a speech on Tuesday, President Donald Trump railed against all things green, clean, and climate-friendly. Climate change is “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world,” Trump said — a scientifically unsound statement, to say the least.

The summit came just days after U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres said the Paris climate agreement is at risk of “collapsing” and that countries needed to ramp up their emissions goals to get things back on track.

Utilities are failing on climate, Sierra Club says

For the past four years, the Sierra Club has annually graded the U.S.’s biggest utilities on their clean-energy progress. The marks haven’t been stellar, but utilities were at least taking steps in the right direction. That is, until this year, when the Sierra Club granted utilities a collective “F,” Canary Media’s Jeff St. John reports.

The “Dirty Truth” report examined 75 of the nation’s biggest utilities to see whether they intend to close their coal plants by 2030, whether they plan to build new gas plants, and how much clean energy they expect to build by 2035. In a spot of good news, 65% of utilities have increased their clean-energy deployment plans since 2021. But they’ve slid backward on fossil fuels, increasing their intended gas-plant additions and walking back plans to shut down coal plants.

You say you want a Revolution? A federal judge lets the Revolution Wind offshore project continue construction in a ruling that signals the Trump administration may have trouble defending its attacks on other already-approved wind farms in court. (Canary Media)

Endangerment fight continues: Every Democratic U.S. senator signs on to a letter opposing the Trump administration’s attempt to rescind the endangerment finding, which establishes that greenhouse gases harm human health, while Republican senators urge the administration to repeal it. (The Hill, Kentucky Lantern)

A clear path forward: Glassmaking for windows, beverage bottles, and other products relies on high heat, typically supplied by fossil fuels, but some global manufacturers are exploring alternatives powered by electricity, hydrogen, and biofuels. (Canary Media)

Turbines keep on turnin’: Nearly a decade after the Block Island offshore wind farm began delivering power, residents of the Rhode Island vacation destination say the five turbines have brought them cleaner, quieter power. (New York Times)

“Motherfucking wind farms”: A viral ad promoting offshore wind development featuring Samuel L. Jackson shows how comedy can bring climate change information to everyday audiences — if it’s not silenced under the Trump administration. (Canary Media)

Heat pumps straight ahead: A coalition of states releases a road map for driving widespread adoption of electric heat pumps as they look to cut emissions from fossil-fuel heating systems. (Canary Media)

From the ground up: In 2014, the northeastern Iowa city of West Union became among the first in the country to install a municipal geothermal network; today, the community is saving money and serving as a model for other cities. (Inside Climate News)

Half of global greenhouse gas emissions are now covered by a 2035 climate pledge following a key UN summit this week, Carbon Brief analysis finds.

China stole the show at the UN climate summit held in New York on 24 September, announcing a pledge to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035.

However, other major emitters also came forward with new climate-pledge announcements at the event, including the world’s fourth biggest emitter, Russia, and Turkey.

Following the summit, around one-third (63) of countries have now announced or submitted their 2035 climate pledges, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs).

The NDCs are a formal five-yearly requirement under the “ratchet mechanism” of the Paris Agreement, the landmark deal to keep temperatures well-below 2C, with aspirations to keep to 1.5C, by the end of this century.

Nations were meant to have submitted these pledges by 10 February of this year, but around 95% of countries missed this deadline.

UN climate chief Simon Stiell then asked laggard countries to make 2035 pledges by the end of September, so they can be included in a report synthesising countries’ climate progress.

At the summit, many nations shared that they were still working on their NDCs and that they would aim to submit them to the UN before or during COP30 in November.

The map below shows countries that submitted their 2035 pledges by the 10 February deadline (dark blue), after the deadline (blue) and that have now announced their pledge, but not yet submitted it formally to the UN registry (pale blue).

The EU has not yet agreed on a 2035 climate pledge. At the UN climate summit, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen announced a “statement of intent” to cut emissions somewhere in the range of 66.3-72.5% below 1990 levels by 2035.

She added that the EU would aim to make its formal NDC submission to the UN before COP30 in November.

The world’s second-largest emitter, the US, submitted its 2035 pledge in 2024 under former president Joe Biden.

However, current president Donald Trump has since signed an order to withdraw the country from the Paris Agreement. Therefore, it is now assumed that the US pledge is now void.

More than 100 nations spoke at the UN climate summit, which was held on the margins of the annual UN general assembly in New York.

Some media outlets mistakenly reported that all of these countries “announced” new pledges at the summit.

However, many of the countries speaking at the summit had already submitted their 2035 pledges, or used their slots to promise to do so at a future date.

Carbon Brief reviewed the six hours of footage from the UN climate summit to get a clear picture of which countries announced new 2035 pledges during the event.

Countries that made new NDC target announcements during the event included China, Russia, Turkey, Palau, Tuvalu, Kyrgyzstan, Peru, São Tomé and Príncipe, Fiji, Bangladesh and Eritrea. (Tuvalu has since submitted its NDC to the UN.)

These countries together represent 36% of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to Carbon Brief analysis. (It is worth noting that China alone accounts for 29% of emissions.)

Some 53 countries have already submitted their 2035 climate pledges to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). These nations account for 14% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Therefore, countries that have either announced or submitted their 2035 climate pledges now represent half of global emissions, according to Carbon Brief analysis. (The 50% figure excludes the US and the EU for the reasons outlined above.)

Despite the new announcements, two-thirds of nations have still not submitted their 2035 climate pledges, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

This includes major emitters, such as India, Indonesia and Mexico.

According to the Hindu, India plans to submit its 2035 climate pledge at the beginning of COP30 on 10 November.

Both Mexico and Indonesia spoke at the UN climate summit. Mexico said it was “still consulting industries” about its proposed target, while Indonesia made no mention of when it might submit its NDC.

Many other nations appearing at the summit made promises to submit their 2035 climate pledges by COP30.

This might mean that many nations miss the end of September deadline set by UN climate chief Simon Stiell to be included in an upcoming NDC synthesis report.

President Xi Jinping has personally pledged to cut China’s greenhouse gas emissions to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035, while “striving to do better”.

This is China’s third pledge under the Paris Agreement, but is the first to put firm constraints on the country’s emissions by setting an “absolute” target to reduce them.

China’s leader spoke via video to a UN climate summit in New York organised by secretary general António Guterres, making comments seen as a “veiled swipe” at US president Donald Trump.

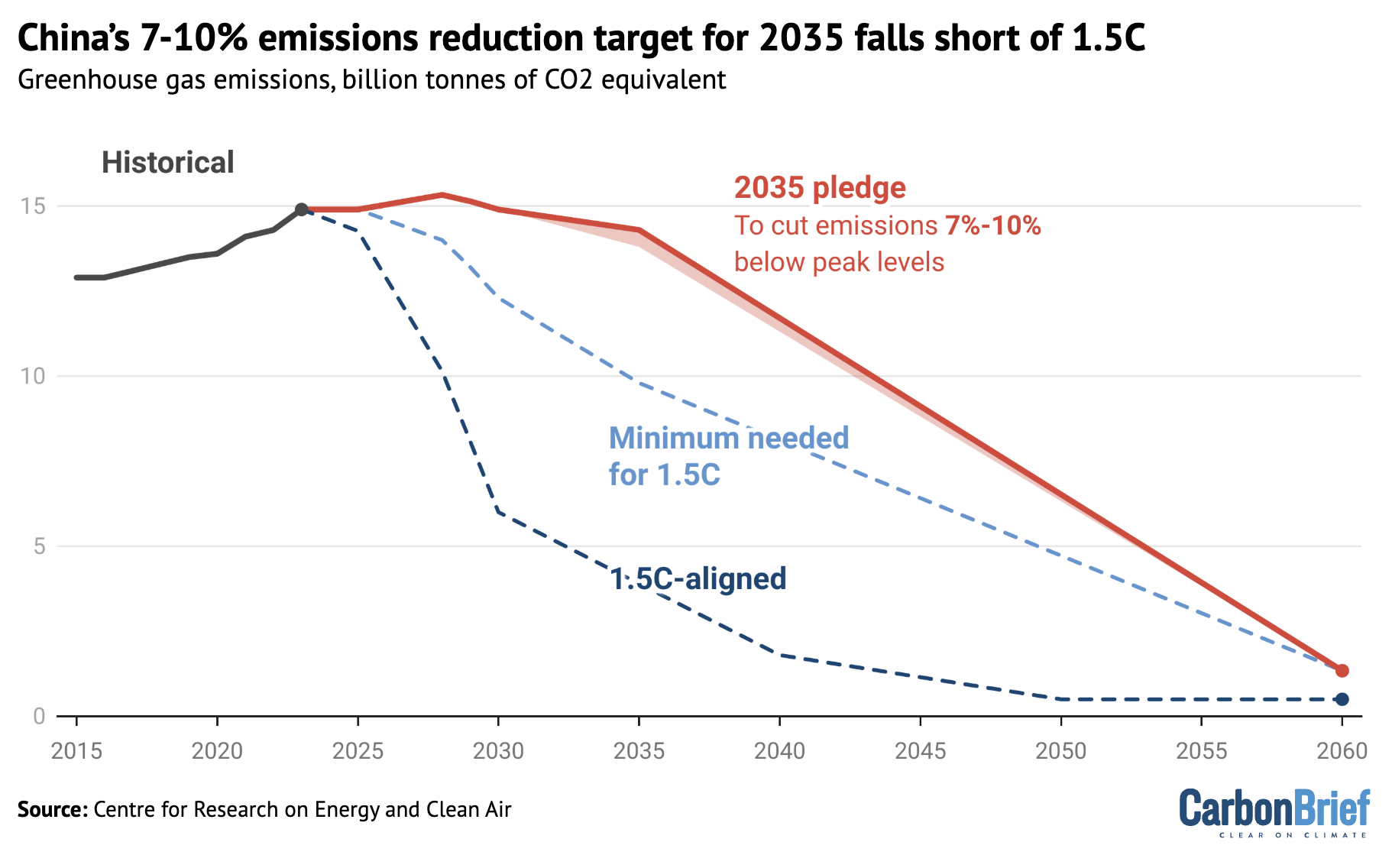

The headline target, with its undefined peak-year baseline, falls “far short” of what would have been needed to help limit warming to well-below 2C or 1.5C, according to experts.

Moreover, Xi’s pledge for non-fossil fuels to make up 30% of China’s energy is far below the latest forecasts, while his goal for wind and solar capacity to reach 3,600 gigawatts (GW) implies a significant slowdown, relative to recent growth.

Overall, the targets for China’s new 2035 “nationally determined contribution” (NDC) under the Paris Agreement have received a lukewarm response, described as “conservative”, “too weak” and as not reflecting the pace of clean-energy expansion on the ground.

Nevertheless, Li Shuo, director of the China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI), tells Carbon Brief that the pledge marks a “big psychological jump for the Chinese”, shifting from targets that constrained emissions growth to a requirement to cut them.

Below, Carbon Brief unpacks what China’s new targets mean for its emissions and energy use, pending further details once its full NDC is formally published in full.

For now, the only available information on China’s 2035 NDC is the short series of pledges in Xi’s speech to the UN.

(This article will be updated once the NDC itself is published on the UN’s website.)

Xi’s speech is the first time his country has promised to place an absolute limit on its greenhouse gas emissions, marking a significant shift in approach.

Xi had previously pledged that China would peak its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions “before 2030”, without defining at what level, reaching “carbon neutrality” by 2060.

He also outlined a handful of other key targets for 2035, shown in the table below against the goals set in previous NDCs.

In his speech, Xi also said that, by 2035, “new energy vehicles” would be the “mainstream” for new vehicle sales, China’s national carbon market would cover all “major high-emission industries” and that a “climate-adaptive society” would be “basically established”.

This is the first time that China’s targets will cover the entire economy and all greenhouse gases (GHGs), a move that has been long signalled by Chinese policymakers.

In 2023, the joint China-US Sunnylands statement, released during the Biden administration, had said that both countries’ 2035 NDCs “will be economy-wide, include all GHGs and reflect…[the goal of] holding the increase in global average temperature to well-below 2C”.

Subsequently, the world’s first global stocktake, issued at COP28 in Dubai, “encourage[d]” all countries to submit “ambitious, economy-wide emission reduction targets, covering all GHGs, sectors and categories…aligned with limiting global warming to 1.5C”.

Responding to this the following year, executive vice-premier and climate lead Ding Xuexiang stated at COP29 in Baku that China’s 2035 climate pledge would be economy-wide and cover all GHGs. (His remarks did not mention alignment with 1.5C.)

This was reiterated by Xi at a climate meeting between world leaders in April 2025.

The absolute target for all greenhouse gases marks a turning point in China’s emissions strategy. Until now, China’s emissions targets have largely focused on carbon intensity, the emissions per unit of GDP, a metric that does not directly constrain emissions as a whole.

The change aligns with China’s broader shift from “dual control of energy” towards “dual control of carbon”, a policy that replaces China’s current tradition of setting targets for energy intensity and total energy consumption, with carbon intensity and carbon emissions.

Under the policy, in the 15th five-year plan period (2026-2030), China will continue to centre carbon intensity as its main metric for emissions reduction. After 2030, an absolute cap on carbon emissions will become the predominant target.

In his UN address, Xi pledged to cut China’s “economy-wide net greenhouse gas emissions” to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035, while “striving to do better”.

This means the target includes not just CO2, but also methane, nitrous oxide (N2O) and F-gases, all of which make significant contributions to global warming. (See: What does China say about non-CO2 emissions?)

The reference to “economy-wide net” emissions means that the target refers to the total of China’s emissions, from all sources, minus removals, which could come from natural sources, such as afforestation, or via “carbon dioxide removal” technologies.

Outlining the targets, Xi told the UN summit that they represented China’s “best efforts, based on the requirements of the Paris Agreement”. He added:

“Meeting these targets requires both painstaking efforts by China itself and a supportive and open international environment. We have the resolve and confidence to deliver on our commitments.”

China has a reputation for under-promising and over-delivering.

Prof Wang Zhongying, director-general of the Energy Research Institute, a Chinese government-affilitated thinktank, told Carbon Brief in an interview at COP26 that China’s policy targets represent a “bottom line”, which the policymakers are “definitely certain” about meeting. He views this as a “cultural difference”, relative to other countries.

The headline target announced by Xi this week has, nevertheless, been seen as falling far short of what was needed.

A series of experts had previously told Carbon Brief that a 30% reduction from 2023 levels was the absolute minimum contribution towards a 1.5C global limit, with many pointing to much larger reductions in order to be fully aligned with the 1.5C target.

The figure below illustrates how China’s 2035 target stacks up against these levels.

(Note that the timing and level of peak emissions is not defined by China’s targets. The pledge trajectory is constrained by China’s previous targets for carbon intensity and expected GDP growth, as well as the newly announced 7-10% range. It is based on total emissions, excluding removals, which are more uncertain.)

Analysis by the Asia Society Policy Institute also found that China’s GHG emissions “must be reduced by at least 30% from the peak through 2035” in order to align with 1.5C warming.

It said that this level of ambition was achievable, due to China’s rapid clean-energy buildout and signs that the nation’s emissions may have already reached a peak.

Similarly, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said last October that implementing the collective goals of the first stocktake – such as tripling renewables by 2030 – as well as aligning near-term efforts with long-term net-zero targets, implied emissions cuts of 35-60% by 2035 for emerging market economies, a grouping that includes China.

In response to these sorts of numbers, Teng Fei, deputy director of Tsinghua University’s Institute of Energy, Environment and Economy, previously described a 30% by 2035 target as “extreme”, telling Agence France-Presse that this would be “too ambitious to be achievable”, given uncertainties around China’s current development trajectory.

In contrast, a January 2025 academic study, co-authored by researchers from Chinese government institutions and top universities and understood to have been influential in Beijing’s thinking, argued for a pledge to cut energy-related CO2 emissions “by about 10% compared with 2030”, estimating that emissions would peak “between 2028 and 2029”.

(Other assessments have pegged relevant indicators, such as emissions and coal consumption, as peaking in 2028 at the earliest.)

The relatively modest emissions reduction range pledged by Xi, as well as the uncertainty introduced by avoiding a definitive baseline year, has disappointed analysts.

In a note responding to Xi’s pledges, Li Shuo and his ASPI colleague Kate Logan write that he has “misse[d] a chance at leadership”.

Li tells Carbon Brief that factors behind the modest target include the “domestic economic slowdown and uncertain economic prospects, the weakening global climate momentum and the turbulent geopolitical environment”. He adds:

“I also think it is a big psychological jump for the Chinese, shifting for the first time after decades of rapid growth, from essentially climate targets that meant to contain further increase to all of a sudden a target that forces emissions to go down.”

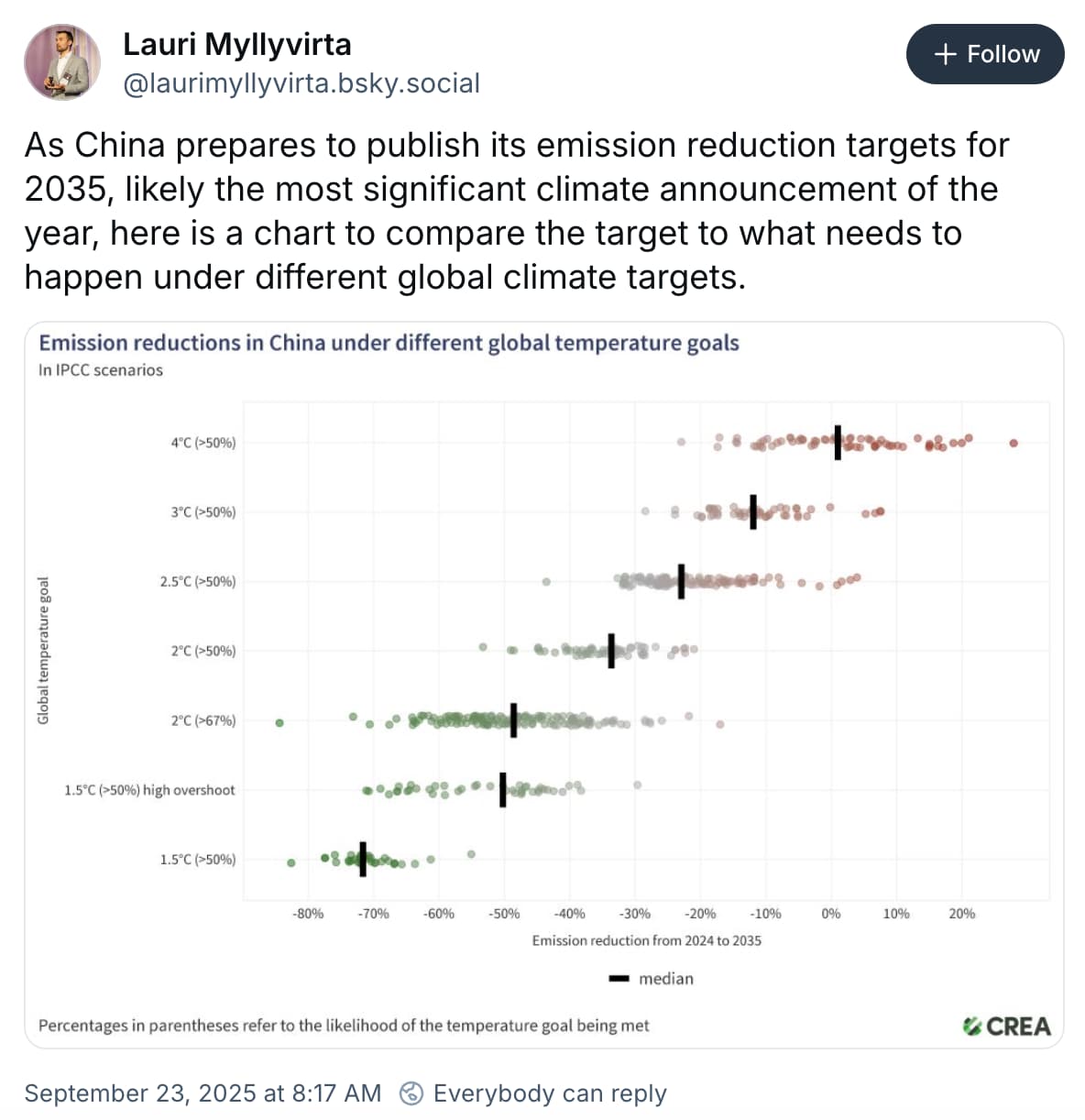

Instead of a target consistent with limiting warming to 1.5C, China’s 2035 pledge is more closely aligned with 3C of warming, according to analysis by CREA’s Lauri Myllyirta.

Climate Action Tracker says that China’s target is “unlikely to drive down emissions”, because it was already set to achieve similar reductions under current policies.

In addition to a headline emissions reduction target, Xi also pledged to expand non-fossil fuels as a share of China’s energy mix and to continue the rollout of wind and solar power.

This continues the trend in China’s previous NDC.

Notably, however, Xi made no mention of efforts to control coal in his speech.

In its second NDC, focused on 2030, China had pledged to “strictly control coal-fired power generation projects”, as well as “strictly limit” coal consumption between 2021-2025 and “phase it down” between 2026-2030. It also said China “will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad”.

It remains to be seen if coal is addressed in China’s full NDC for 2035.

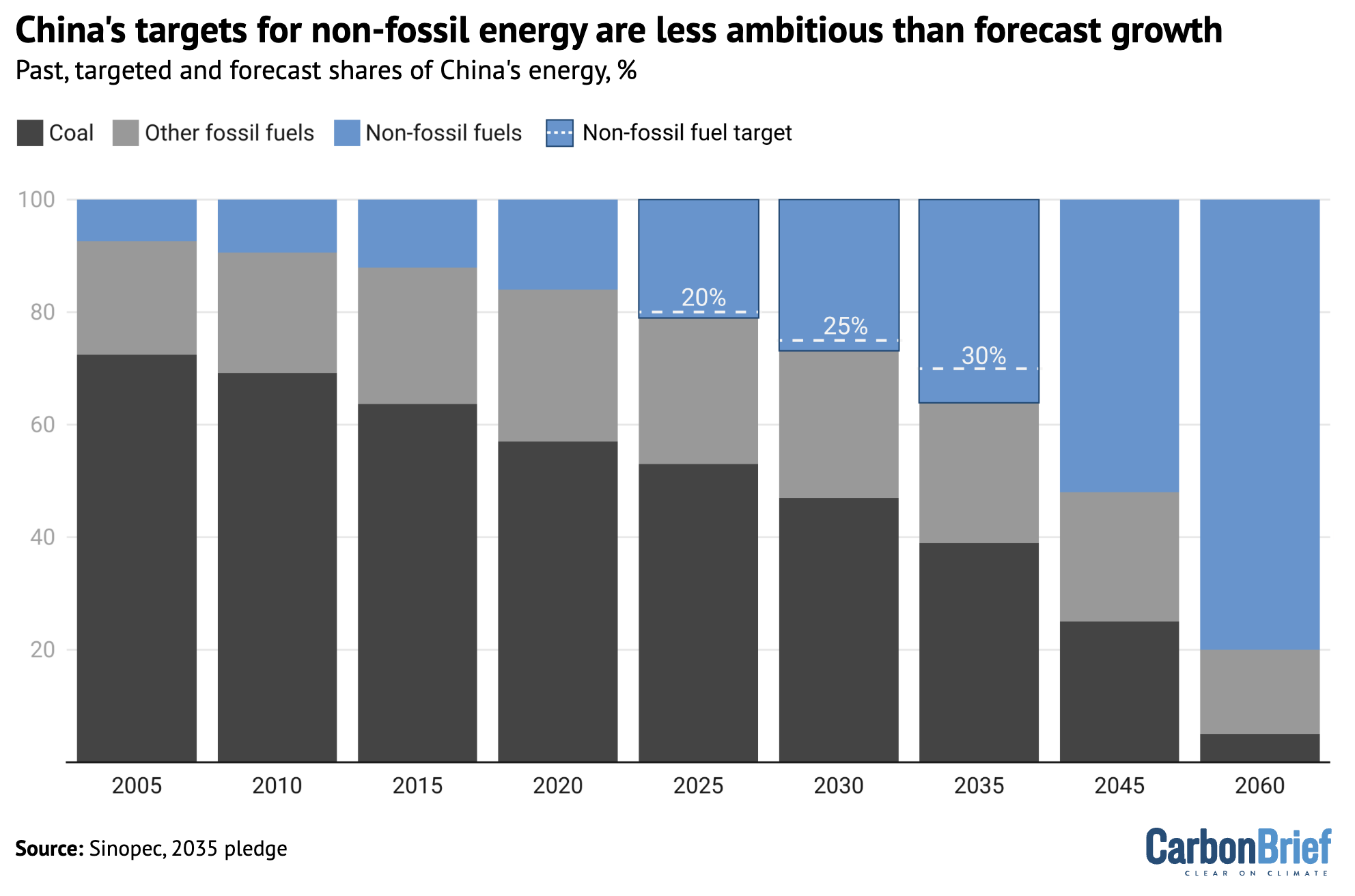

The 2030 NDC also stated that China would “increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 25%” – and Xi has updated this to 30% by 2035.

These targets are shown in the figure below, alongside recent forecasts from the Sinopec Economics and Development Research Institute, which estimated that non-fossil fuel energy could account for 27% of primary energy consumption in 2030 and 36% in 2035.

As such, China’s targets for non-fossil energy are less ambitious than the levels implied by current expectations for growth in low-carbon sources.

In a recent meeting with the National People’s Congress Standing Committee – the highest body of China’s state legislature – environment minister Huang Runqiu said that progress on China’s earlier target for increasing non-fossil energy’s share of energy consumption was “broadly in line” with the “expected pace” of the 2030 NDC.

On wind and solar, China’s 2030 NDC had pledged to raise installed capacity to more than 1,200GW – a target that analysts at the time told Carbon Brief was likely to be beaten. It was duly met six years early, with capacity standing at 1,680GW as of the end of July 2025.

Xi has set a 2035 target of reaching 3,600GW of wind and solar capacity.

This looks ambitious, relative to other countries and global capacity of around 3,000GW in total as of 2024, but represents a significant slowdown from the recent pace of growth.

Given its current capacity, China would need to install around 200GW of new wind and solar per year and 2,000GW in total to reach the 2035 target. Yet it installed 360GW in 2024 and 212GW of solar alone in the first half of this year.

Myllyvirta tells Carbon Brief this pace of additions is “not enough to even peak emissions [in the power sector] unless energy demand growth slows significantly”.

While the pace of demand growth is a key uncertainty, a recent study by Michael R Davidson, associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, with colleagues at Tsinghua University, suggested that deploying 2,910-3,800GW of wind and solar by 2035 would be consistent with a 2C warming pathway.

Davidson tells Carbon Brief that “most experts within China do not see the [recent] 300+GW per year growth as sustainable”. Still, he adds that the lower levels outlined in his study could be consistent with cutting power-sector emissions 40% by 2035, subject to caveats around whether new capacity is well-sited and appropriately integrated:

“We found that 40% emissions reductions in the power sector can be supported by 3,000-3,800GW wind and solar capacity [by 2035]. Most of the capacity modeling really depends on integration and quality of resources.”

Renewable energy’s share of consumption in China has lagged behind its record capacity installations, largely due to challenges with updating grid infrastructure and economic incentives that lock in coal-fired power.

In Davidson’s study, capacity growth of up to 3,800GW would see wind and solar reaching around 40% of total power generation by 2030 and 50% by 2035.

Meanwhile, China will need to install around 10,000GW of wind and solar capacity to reach carbon neutrality by 2060, according to a separate report by the Energy Research Institute, a Chinese government-affilitated thinktank.

This is the first time that one of China’s NDC pledges has explicitly covered the emissions from non-CO2 GHGs.

However, while Xi’s speech made clear that China’s headline emissions goal for 2035 will cover non-CO2 gases, such as methane, nitrous oxide and F-gases, he did not give further details on whether the NDC would set specific targets for these emissions.

In China’s 2030 NDC, the country stated it would “step up the control of key non-CO2 GHG emissions”, including through new control policies, but did not include a quantitative emissions reduction target.

In preparation for a comprehensive greenhouse gas emissions target, China has issued action plans for methane, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs, one type of F-gas) and nitrous oxide.

The nitrous oxide action plan, published earlier this month, called for emissions per unit of production for specific chemicals to decrease to a “world-leading level” by 2030, but did not set overarching limits.

Similarly, the overarching methane action plan, issued in late 2023, listed several key tasks for reducing emissions in the energy, agriculture and waste sectors, but lacked numerical targets for emissions reduction.

A subsequent rule change in December 2024 tightened waste gas requirements for coal mines. Under the new rules, Reuters reports, any coal mine that releases “emissions with methane content of 8% or higher” must capture the gas, and either use or destroy it – down from a previous threshold of 30%.

But analysts believe that the true challenge of coal-mine methane emissions may come from abandoned mines, which, one study found, have surged in the past 10 years and will likely overtake emissions from active coal mines to become the prime source of methane emissions in the coal sector.

As the demand for coal could be facing a “structural decline”, the number of abandoned mines is expected to grow significantly.

Meanwhile, the HFC plan did set quantitative targets. The country aims to lower HFC production by 2029 by 10% from a 2024 baseline of 2GtCO2e, while consumption would also be reduced 10% from a baseline of 0.9gtCO2e in this timeframe – in line with China’s obligations under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on ozone protection.

From 2026, China will “prohibit” the production of fridges and freezers using HFC refrigerants.

However, the action plan does not govern China’s exports of products that use HFCs – a significant source of emissions.

Illinois could start turning homes and businesses into “virtual power plants” with solar-powered batteries aiding the grid, under a bill that has been gaining momentum in the state legislature.

In Puerto Rico, Vermont, California, Texas, and other states, virtual power plants have helped the grid survive spikes in demand, avoiding outages or the need to fire up gas-fueled peaker plants, and saving consumers money.

Illinois is among the areas expecting electricity demand to grow rapidly because of new data centers; meanwhile, the state is mandated to phase out fossil-fuel generation by 2045, and residential and commercial solar have boomed thanks to state incentive programs. If those solar arrays were paired with batteries, they could provide crucial clean power to the grid during high demand.

HB 4120, an ambitious bill that Illinois lawmakers may consider during an October veto session, would create a basic virtual power plant (VPP) program while mandating that the state’s two largest utilities — ComEd and Ameren — propose their own VPP programs by 2027.

The bill’s plan would offer a rebate to customers who purchase a battery, if they agree to let the battery be tapped for several hours a day during the summer months, when air conditioners drive up electricity use.

The Illinois proposal is less nuanced and comprehensive than VPP programs in other states. For example, in Vermont, Green Mountain Power subsidizes the purchase of batteries, which the utility can then tap while also controlling customers’ smart thermostats, EV chargers, and water heaters whenever the grid is stressed.

But stakeholders in the solar and energy storage industry say Illinois’ proposal is an important first step, opening the door for more ambitious VPP services.

“A utility may want a program to address ‘emergency calls’ to reduce peak load, or deal with a winter peaking issue, or address locational capacity constraints,” said Amy Heart, senior vice president of public policy at Sunrun, a national company that has invested heavily in Illinois solar and that runs VPPs in Puerto Rico, California, and other places. “There is an official pathway and timeline for all of this.”

Energy players in Illinois have been talking seriously about VPPs for several years, during negotiations over what has now become HB 4120. The legislation would incentivize the construction of large-scale energy storage in Illinois, through procurement by the state power agency. VPPs, meanwhile, would provide a decentralized form of storage.

Under the bill’s VPP program, residential customers would get a rebate of $300 per kilowatt-hour on the capacity of the battery they purchase, and then receive at least $10 per kilowatt during scheduled dispatches from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays in June, July, August, and September for a five-year period. “It’s sort of a ‘set-it and forget-it’ program,” said Heart.

Illinois residents already receive a rebate for the same amount when they purchase a battery, but with the new rules, consumers would need to participate in the VPP program to qualify.

All community solar projects with storage would be required to participate in the VPP program, dispatching from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m.

ComEd, which serves northern Illinois, and Ameren, which serves most of the rest of the state, could petition the Illinois Commerce Commission for permission to tap the batteries on a different schedule, for no more than two or three hours a day over 80 days each year.

The basic program would not help with peak demand during unscheduled times — like unexpectedly hot fall weather. But at least utilities would be guaranteed power during the scheduled peaks, said Heart.

“People wanted to move quickly,” on getting a VPP program in the legislation, she added. “You avoid delays [caused by] trying to make this perfect. Industry is talking about how we need stability; nonprofits, ratepayer advocates, utilities, [and] labor are all talking about why we need these investments.”

Illinois, like many states, has demand-response programs that are often considered part of virtual power plants, helping people reduce their energy use during peak demand. And ComEd has already proposed a VPP program to state regulators.

But legislation is crucial for VPPs to really take off, to ensure that programs “feature robust participation, innovation by aggregators, and a wide range of benefits,” said Samarth Medakkar, policy principal for Advanced Energy United, a national trade association of power, transportation, and software companies focused on clean energy.

Illinois’ bill would permit third-party aggregators to manage VPP deployment, a common setup in other states wherein a company, like Virtual Peaker in Vermont, coordinates battery deployment and demand response for the customer and utility.

ComEd and Ameren would be required to file reports by the end of 2028 detailing how many people have enrolled in the VPP program and its effects on energy supply.

By the end of 2027, the companies would have to file proposals for their own VPP programs, which the state regulatory commission must approve by the close of 2028. Those programs would need to include higher incentives for low- to moderate-income customers, “community-driven” community solar projects, and areas targeted for equity investments in Illinois’ existing energy laws.

“VPPs have a huge potential in a state like Illinois, where there are already many capable devices — like smart thermostats and solar systems which can pair with storage — increasing in number at a rate we can accelerate,” said Medakkar.

An analysis conducted by clean-energy think tank RMI found that VPPs could meet most of the expected new demand in Illinois, providing a crucial bridge while more clean-power generation and transmission lines are built.

The report notes that the state will need around 3.9 gigawatts of new generation or energy savings by 2029, as demand grows and old fossil-fueled plants retire.

VPPs could satisfy about three-quarters of that need, the analysis says, if they account for 10% of electricity used during peak demand times by tapping batteries and dialing down customers’ energy consumption.

Plus, it takes much less time to set up a VPP than to build a new traditional power plant. “VPPs can be deployed in as little as six months, nearly three years quicker than the median deployment timelines for utility-scale batteries and natural gas plants,” notes the RMI report, which was produced for Advanced Energy United to inform the legislative process.

The analysis determined that VPPs would save the average Illinois customer $34 a year by reducing the amount of expensive capacity that utilities would have to purchase in the auctions run by regional grid operators. ComEd’s customers especially are seeing their bills skyrocket due to record-high capacity costs in the PJM regional market.

“There’s great untapped potential in demand-response and VPP-type products,” said Sarah Moskowitz, executive director of the Citizens Utility Board, which advocates for Illinois’ electric and gas customers. “It’s disappointing we haven’t seen more opportunities of this sort take root here. But maybe now, with the spiraling energy prices, policymakers will finally see that these are programs that can bring real benefit not just to those who directly participate but to everybody.”

A year after Hurricane Helene hit western North Carolina — dumping as much as 30 inches of rain and felling thousands of trees — countless homes still suffer from leaky roofs, mold and mildew, and rotting floors.

All that damage doesn’t just threaten residents’ comfort, health, and safety. Unless it’s resolved, low-income households can’t access free energy-efficiency retrofits that could save them hundreds of dollars each year on their utility bills.

Now, North Carolina plans to solve that problem by allocating $10 million to urgent home repair in the region. Officials in the administration of Gov. Josh Stein, a Democrat, hope the funds will aid more than 575 households in the counties most devastated by Helene.

“This effort is going to increase western North Carolina’s sound and efficient housing stock, reduce energy costs for the most vulnerable families and individuals, and make homes safer and more comfortable,” Julie Woosley, director of the State Energy Office, said in a statement.

Drawing on a disaster-relief package passed by lawmakers in the early aftermath of Helene, the home-repair monies will be distributed to a regional government entity and nine community action agencies that implement the federal Weatherization Assistance Program.

Established nearly a half century ago, the weatherization initiative is aimed at families below certain annual income thresholds; for example, a family of four must earn about $60,000 or less to qualify. The program’s services — including sealing leaks around doors and windows, adding insulation, and improving appliance efficiency — benefit hundreds of North Carolina households each year, lowering their utility bills by up to $300.

But the Weatherization Assistance Program only scratches the surface of need for the energy burdened. Because its funds are restricted to minor repairs and mostly can’t be used for major ones such as roof replacement, about one in five families nationwide are deferred from receiving benefits, according to a survey by the nonprofit American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. Of those, 40% never get weatherized at all.

That’s why the newly announced money for western North Carolina households is so vital, said Claire Williamson, energy policy advocate at the North Carolina Justice Center: It will unlock assistance for households that have previously been unable to access weatherization aid.

“It’s not only helping families recovering from Hurricane Helene,” Williamson said, “but also helping these families not be burdened by rising energy costs.”

To be sure, there are several existing efforts to bridge the gap for households that need energy-efficiency retrofits as well as major repairs. Some municipalities have their own fix-it programs, Williamson said, as does the North Carolina Housing Finance Agency.

For Duke Energy customers, Williamson’s group helped win $16 million for urgent home fixes financed by shareholders. But the predominant utility doesn’t serve the state’s farthest-flung counties, including some heavily hit by Helene.

“It’s fantastic that pre-weatherization dollars can be used for people who are members of electric cooperatives,” she said. “Otherwise, these households are getting left behind.”

The $10 million announcement from the State Energy Office comes at a crucial time for weatherization efforts statewide. In 2021, the program got a $90 million boost from the federal bipartisan infrastructure law — funding not yet swept up in the Trump administration’s assault on clean energy and energy efficiency.

After months of planning, the Stein administration says those funds will be deployed starting in January and spent by the end of the decade, with hopes of serving around 2,000 households annually. The plan includes up to $12.6 million for major health and safety repairs.

“It’s such a great sign that the state is dedicating funds to this issue,” Williamson said. “When homes are more efficient, it helps benefit the rest of North Carolina,” she added. “They’re lowering energy use and lowering their impact on the grid.”

Microsoft says it will get green steel from a first-of-a-kind facility in northern Sweden as the tech giant looks to curb the climate impact of its data center build-out.

This week, Microsoft announced a two-part deal with Stegra (formerly H2 Green Steel), which is building a multibillion-dollar plant set to be completed in late 2026. Instead of relying on traditional coal-based methods, the Swedish project will produce steel using green hydrogen — made from renewable energy sources — and clean electricity.

The first part of Microsoft’s agreement involves actual coils of steel. Because the company doesn’t directly buy construction materials itself, Microsoft has agreed to work with its equipment suppliers to ensure that Stegra’s green steel is used in some of its data center projects in Europe.

The second part of the deal enables Microsoft to claim green credentials for the infrastructure it builds outside of Europe, where Stegra isn’t planning to operate. Under this scheme, Stegra will sell its “near-zero emission” steel into the European market — except that the metal will be sold as if it had an industry-average carbon footprint and without a price premium. Microsoft will then buy “environmental attribute certificates” that represent the emissions reductions provided by Stegra’s product, helping to cover the extra cost of making green steel.

With the certificates, “We aim to signal demand, enable project financing, and accelerate global production,” Melanie Nakagawa, Microsoft’s chief sustainability officer, said in a Sept. 23 press release. Ultimately, she said, “The end game is to source physical materials with the lowest possible CO₂ footprint. Achieving this requires greater volumes of low-carbon steel available in more regions.”

The world produces roughly 2 billion metric tons of steel every year, most of which is made using dirty coal-fueled furnaces. As a result, the industry is responsible for between 7% and 9% of total global carbon emissions.

Microsoft and Stegra didn’t provide details about the financial value or volumes of steel tied to their deal. Johan M. Reunanen, who leads Stegra’s climate impact work, said only that its contract with Microsoft is neither the biggest nor the smallest offtake agreement that the steelmaker has signed since launching in 2021.

“But it’s very strategic for us,” Reunanen told Canary Media during a visit to New York for Climate Week NYC. “It gives Stegra access to a customer that is in data centers, which is a market that we’ll be developing.”

Stegra isn’t the only Swedish steelmaker chasing Big Tech. Last year, the manufacturer SSAB signed an agreement with Amazon Web Services to supply hydrogen-based steel for one of Amazon’s three new data centers in Sweden. SSAB operates the Hybrit pilot plant in Luleå — the world’s first steelmaking facility to use hydrogen at any meaningful scale, though the Stegra project will be the first large-scale plant to use this approach once completed.

Microsoft’s agreement with Stegra arrives at a tenuous time for developers of green hydrogen.

More than a dozen hydrogen projects have been canceled, postponed, or scaled back in recent months owing to soaring production costs and waning demand for the low-carbon and highly expensive fuel, Reuters reported in late July. That includes ArcelorMittal’s hydrogen-based steelmaking initiative in Germany, which the company shelved in June, as well as U.S. green steel projects formerly planned in Ohio and Mississippi.

Stegra, for its part, is seeking to raise additional cash to complete its flagship project in Boden, Sweden, after a government agency denied the company 165 million euros ($193 million) in previously approved grant funding. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency reportedly objected to the fact that the steel mill will use some fossil gas during a heat-treatment process — though Stegra claims the project could still cut emissions by up to 95% compared to coal-based steelmaking.

Stegra has already secured 6.5 billion euros ($7.6 billion) from private investors for the project, which broke ground in 2022. The company is installing 740 megawatts’ worth of electrolyzers to convert electricity from the region’s hydropower plants and wind farms into hydrogen gas. The hydrogen will be used in the “direct reduction” process to convert iron ore into iron, which will then be transformed into steel using electric arc furnaces.

The sprawling facility, located just south of the Arctic Circle, is expected to produce 2.5 million metric tons of steel by 2028, before ramping up to make 5 million metric tons by 2030. Reunanen said that more than half of the steel produced during the first phase is already covered by offtake contracts with automakers like Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, and Scania, as well major companies including Cargill, Ikea, and now Microsoft.

The tech firm — which previously invested in Stegra through its $1 billion Climate Innovation Fund — is the first company to commit to buying environmental attribute certificates from a steel facility. Microsoft has struck similar deals to help drum up demand for lower-carbon versions of other industrial materials, including with cement startup Fortera and alternative-jet-fuel producers like World Energy.

RMI, a think tank focused on clean energy, said it helped advise Stegra and Microsoft on their deal, and both companies are part of an RMI initiative that’s working to design tools that track, validate, and account for certificates.

“Agreements like this one signal a wider demand pool for lower-carbon steel, expanding the offtake beyond conventional direct steel purchasers and into sectors where steel is a critical yet buried part of the supply chain,” said Claire Dougherty, a senior associate at RMI. She added that the deal “serves as a proof-of-concept for the role that [certificates] can play in getting first-of-a-kind, near-zero steel projects off the ground.”

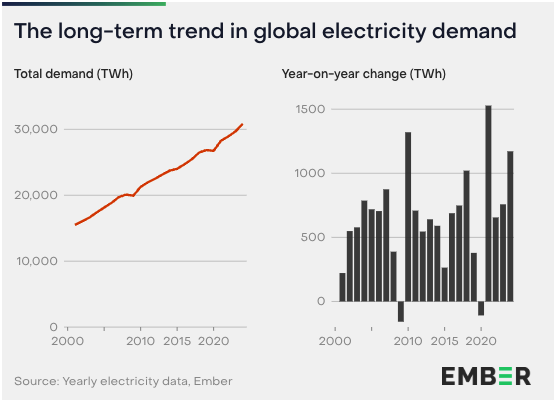

01 Electricity demand saw the third-largest absolute increase ever in 2024

02 China’s per capita electricity use overtook France’s for the first time in 2024, and was five times that of India’s

03 A fifth of the demand increase in 2024 was due to the impacts of hotter temperatures compared to 2023

Global electricity demand increased by 4% (+1,172 TWh) in 2024. This was the third-largest absolute increase in electricity demand ever, only surpassed by rebounds in demand in 2010 from the global recession and in 2021 from the Covid-19 pandemic. This increase is significantly above the average annual demand growth of 2.5% in the previous ten years (2014-2023).

Global electricity demand rose to 30,856 TWh, crossing 30,000 TWh for the first time. Since the turn of the century, electricity demand has doubled.

Some of the exceptional growth in 2024 was due to weather conditions. As explored in chapter 1, we calculate that hotter temperatures added 0.7% to global demand in 2024. Nonetheless, emerging drivers of electricity demand such as electric vehicles (EVs), data centres and heat pumps also added 0.7% to global demand growth in 2024 (+195 TWh), a slight step up from the 0.6% they added in 2023 (+174 TWh). See more in chapter 2.2.

China recorded the largest increase in electricity demand, adding 623 TWh (+6.6%), which accounted for more than half of the global increase. The US saw a rise of 128 TWh (+3%). India’s demand increased by 98 TWh (+5%). As recent Ember analysis shows, all three countries experienced heatwaves that drove up electricity demand beyond increases due to economic activity.

Other countries with substantial increases were Brazil (+35 TWh, +4.9%), Russia (+32 TWh, +2.8%), Viet Nam (+26 TWh, +9.5%) and Türkiye (+18 TWh, +5.6%).

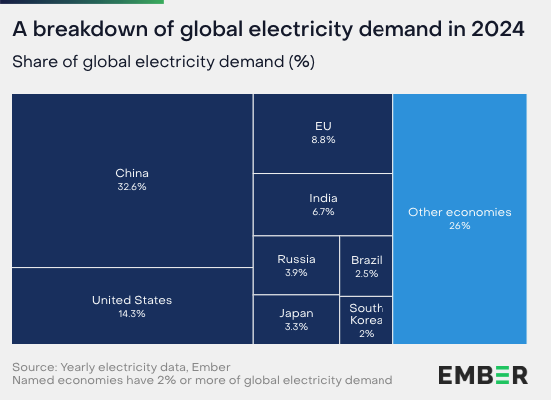

China’s share of global electricity demand has increased due to its continued demand growth above the world average. With 10,066 TWh, China’s electricity demand contributed roughly a third (32.6%) of the global total, up from 28% five years ago.

China’s global share of demand was more than double that of the US at 4,401 TWh (14.3% of the global total). The EU made up 8.8% (2,727 TWh) of global electricity demand. India’s electricity demand reached 2,054 TWh (6.7% of global demand).

26% of global electricity demand comes from economies that each contribute less than 2%.

Among the top ten electricity consumers, the difference in per capita consumption remained vast. Canada had the highest per capita demand for electricity at 15.5 megawatt hours (MWh). This was more than 10 times higher than India, which places last among this group at 1.4 MWh.

China’s per capita demand (7.1 MWh) was almost double the world average of 3.8 MWh, overtaking France in 2024 and Germany in 2023.

Asia’s electricity demand has grown fourfold since the turn of the century from 4,199 TWh in 2000 to 16,153 TWh in 2024 (+285%), driven by demand increases in China, and increasingly India, Indonesia, Viet Nam and other fast-growing economies.

This trend was not replicated elsewhere. Demand outside Asia grew by just 3,624 TWh (+33%) over the same period, from 11,079 TWh to 14,703 TWh.

Despite moderate increases in the past decade, the entire continent of Africa accounted for just 3.1% of total global electricity demand in 2024, less than Japan.

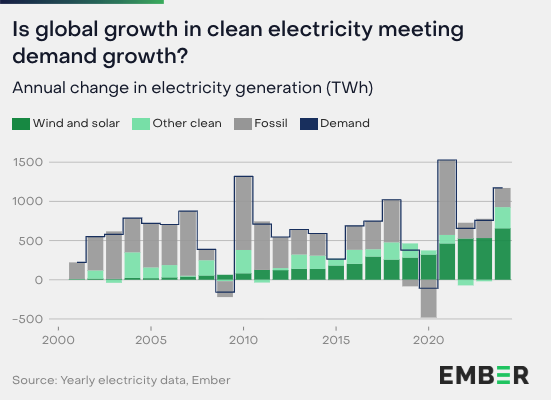

01 Low-carbon sources surpassed 40% of global electricity generation, driven by record renewables growth

02 Global solar generation has doubled in three years, continuing its pattern of exponential growth

03 Wind and solar have met more than half of global growth in electricity demand since 2015

In 2024, low-carbon power sources rose to 40.9% of global electricity generation, the highest level since the 1940s when hydro generation alone met over 40%.

Solar and wind power are the fastest-growing sources of electricity. Combined, they accounted for 15% of global electricity in 2024, with solar contributing 6.9% and wind 8.1%. The two sources combined now produce more electricity than hydropower at 14.3%. They already surpassed nuclear generation in 2021, which continues to reduce in share (9% in 2024). The rise in wind and solar power over recent years has been remarkable, with solar in particular maintaining rapid growth rates despite reaching high levels of absolute generation. Solar power has doubled in the three years since 2021, continuing its pattern of exponential growth.

The share of fossil sources declined to 59.1% in 2024, despite increases in absolute generation. It has declined substantially since the peak of 68.3% in 2007 and is set to fall further in the coming years as renewable generation growth continues to accelerate. The share of coal generation has fallen significantly, from 40.8% in 2007 to 34.4% in 2024, with more consistent falls in the last 10 years. The share of gas generation has fallen for four consecutive years since it peaked in 2020 at 23.9%, reaching 22% in 2024.

Clean generation met 79% of the increase in global electricity demand in 2024. Electricity generation from clean sources grew by 927 TWh (+7.9%), the largest increase ever recorded. The clean generation increase in 2024 would have been large enough to meet the rise in electricity demand in all but three years in the last two decades.

However, heatwaves in 2024 elevated cooling demand, which was the main driver of a small 1.4% increase in fossil generation (+245 TWh), similar to the rise in the previous two years. Without the impact of hotter temperatures, fossil generation would have remained flat.

Renewables growth alone met 73% of the increase in electricity demand. In total, renewable power sources added a record 858 TWh of generation in 2024, 49% more than the previous record set in 2022 of 577 TWh.

Solar dominated the growth in electricity generation as it was the largest source of new electricity for the third year in a row. Solar added 474 TWh (+29%) in 2024. Solar’s increase alone met 40% of global electricity demand growth in 2024. Wind growth remained more moderate (+182 TWh, +7.9%), with lower wind speeds in some geographies leading to the lowest increase in wind generation in four years despite continued capacity additions. Hydro generation rebounded in 2024 (+182 TWh) as drought conditions in 2023 eased, particularly in China.

Nuclear generation increased by 69 TWh (+2.5%), mostly as a result of less downtime for reactors in France as well as small increases from new reactors in China.

The global increase in fossil generation came mostly from coal which rose by 149 TWh (+1.4%). Gas generation increased by 103 TWh (+1.6%). Other fossil fuels saw a minor fall of 7.7 TWh (-0.9%).

China and India saw the largest increases in coal generation in 2024, together totalling more than the global net increase. The gas generation growth in the US alone (+59 TWh, +3.3%) was equivalent to 57% of the global increase. Gas generation in the US is rising mainly as a result of coal-to-gas switching. Ember’s analysis shows that heatwaves also played a role in raising fossil generation in China, India and the US in 2024.

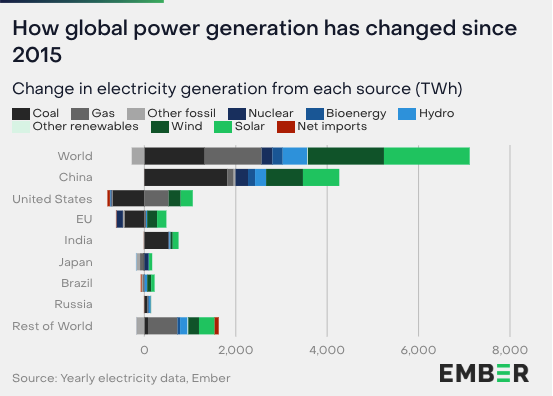

Since 2015, solar and wind have been the two largest-growing sources of electricity, meeting more than half (52%) of global demand growth. Solar generation has grown eightfold since 2015, from 256 TWh in 2015 to 2,131 TWh in 2024. Wind generation tripled from 830 TWh in 2015 to 2,494 TWh in 2024.

China has dominated changes in the global electricity system since 2015, recording the largest increases of any country for solar, wind, hydro, nuclear and coal. China accounts for 45% of global growth in wind and solar generation since 2015. At the same time, global coal generation would have fallen since 2015 without the increase in China.

India saw the second-largest increase in coal generation behind China. India’s rise in coal generation was equivalent to 40% of the global increase in coal since 2015.

The US was responsible for 43% of the global increase in gas generation since 2015. Its gas generation increased by 40% (+531 TWh) over the same period.

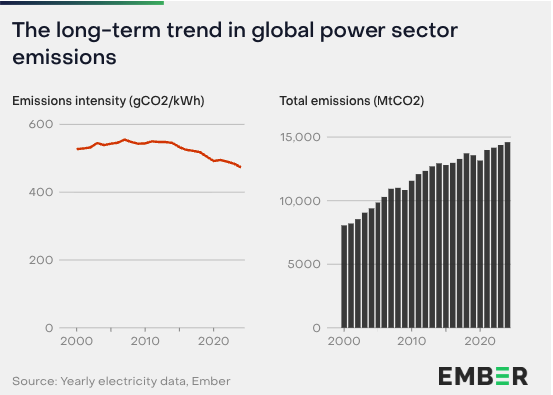

01 Power sector emissions hit a new record high as heatwaves drove a small rise in fossil generation

02 Carbon intensity fell by 15% since its peak in 2007, driven by clean generation growing faster than fossil generation

03 Africa and Latin America each make up less than 4% of global power sector emissions, despite representing 19% and 8% of the global population respectively

Global power sector emissions reached a new record high in 2024, rising by 1.6% or 223 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2), compared to 2023. This increase was similar to 2023 (+1.5%) and 2022 (+1.3%) and was driven by an increase in fossil generation, predominantly from coal. However, without the impact of 2024’s heatwaves, fossil generation would only have risen by 0.2% from 2023, and power sector emissions would have remained almost unchanged (see Chapter 1).

Despite the overall increase in power sector emissions, the emissions intensity (emissions per unit of electricity produced) of global power generation continued to decrease. Emissions intensity dropped by 2.3% to 473 grams of CO2 per kilowatt hour (gCO2/kWh), down from 484 gCO2/kWh in 2023. Emissions intensity has now fallen in nine of the last ten years, with the only increase occurring in 2021 as fossil generation rebounded following large falls in demand during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The decline in emissions intensity is driven by the growing share of clean power in the mix, which reached 40.9% in 2024. As of 2024, the emissions intensity of the global power sector has fallen by 15% since the peak of 555 gCO2/kWh in 2007.

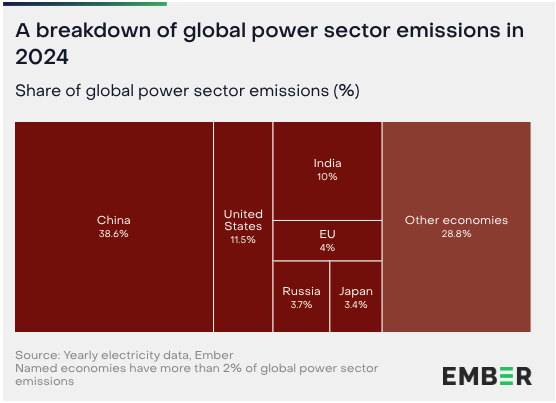

China’s size and reliance on coal generation kept it as the world’s highest power sector emitter in 2024, with emissions reaching 5,640 MtCO2, four times those of the US and India.

Emissions from power generation in the US amounted to 1,683 MtCO2, accounting for 11.5% of the global total. India’s power sector emissions reached 1,457 MtCO2, now close to matching the US and reaching 10% of global power sector emissions for the first time.

China accounted for 38.6% of global power sector emissions – more than the US, India, the EU, Russia and Japan combined. Countries individually producing less than 2% of global power sector emissions made up the remaining 28.8% of the global total.

India and China had the highest emissions intensity of electricity production among the top ten electricity consumers. India’s emissions intensity remained particularly high at 708 gCO2/kWh, compared to the global average of 473 gCO2/kWh. However, India’s emissions intensity has been falling as clean generation has been growing faster than coal.

Canada, Brazil and France had the lowest emissions intensity due to their high shares of low-carbon generation from hydro and nuclear, along with a growing share of wind and solar.

Despite this, Canada’s emissions per capita (2.8 tCO2) were nearly three times larger than India’s (1 tCO2), driven by substantially higher per capita demand for electricity.

South Korea (5 tCO2) and the US (4.9 tCO2) had the highest power sector emissions per capita among the ten biggest electricity consumers due to a combination of high per capita electricity demand and a high share of fossil generation in the mix. China’s emissions per capita have risen to match Japan’s at 4 tCO2.

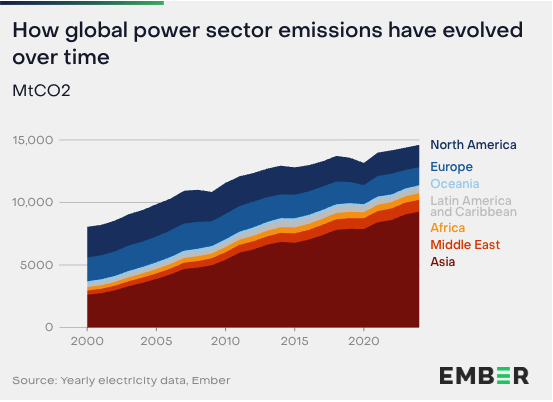

Driven by rapidly growing electricity demand in Asian economies, Asia’s share of global power sector emissions has surged over the last two decades. In 2000, Asia made up a third (33%) of global power sector emissions. In 2024, this had risen to nearly two-thirds (63%).

Power sector emissions in North America and Europe have both fallen by a third since peaking in 2007. Within Europe, EU power sector emissions have halved (-52%) since 2007, whilst emissions in Russia and Türkiye have risen. In the Middle East, emissions have risen more sharply, driven by growing electricity demand in large markets such as Saudi Arabia and Iran, where fossil fuels dominate the electricity mix.

In 2024, African countries still only made up 3.6% of global power sector emissions, despite accounting for 19% of the world’s population. Similarly, Latin America and the Caribbean contributed just 3.2% of global power sector emissions while representing 8% of the global population.

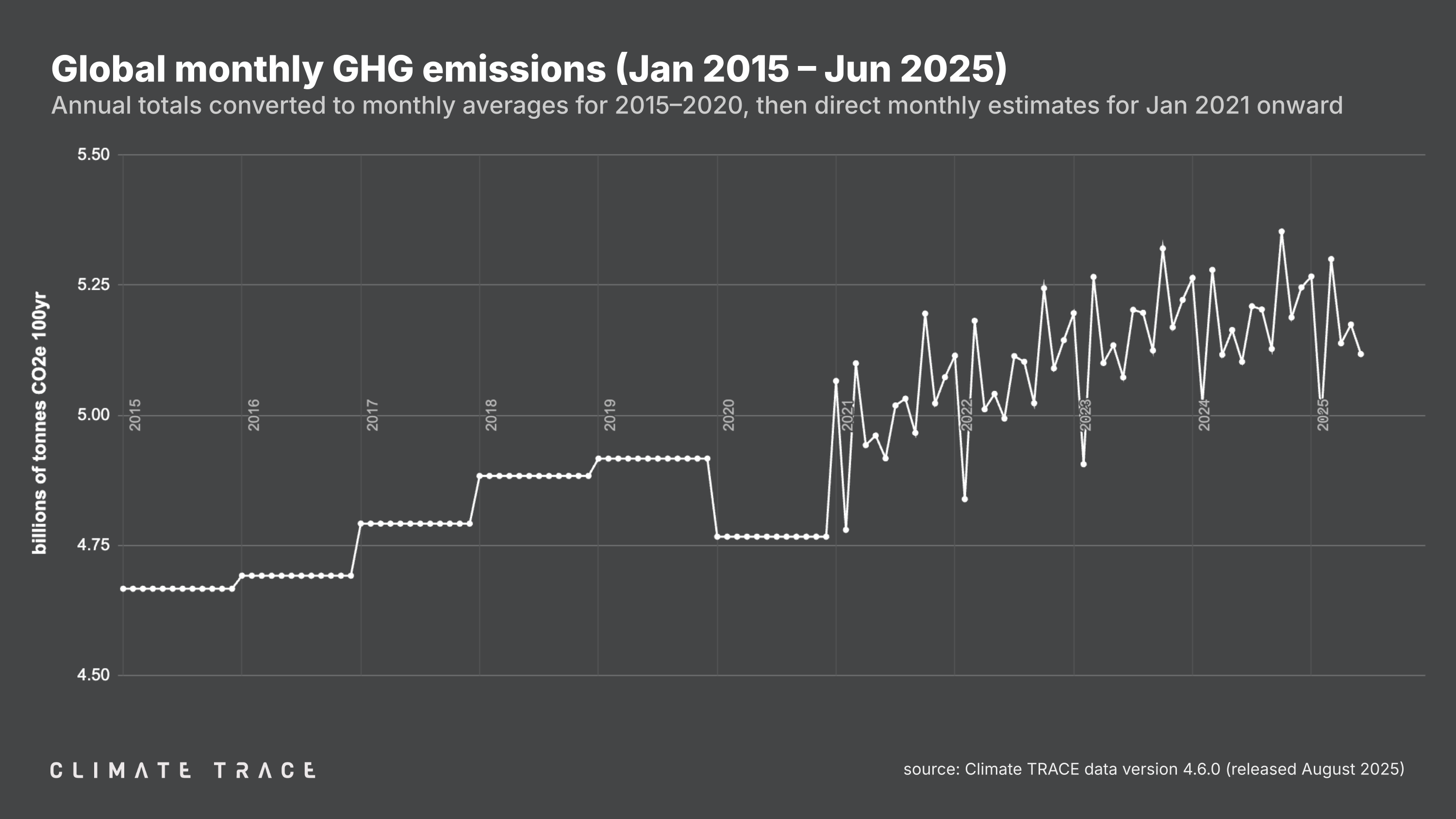

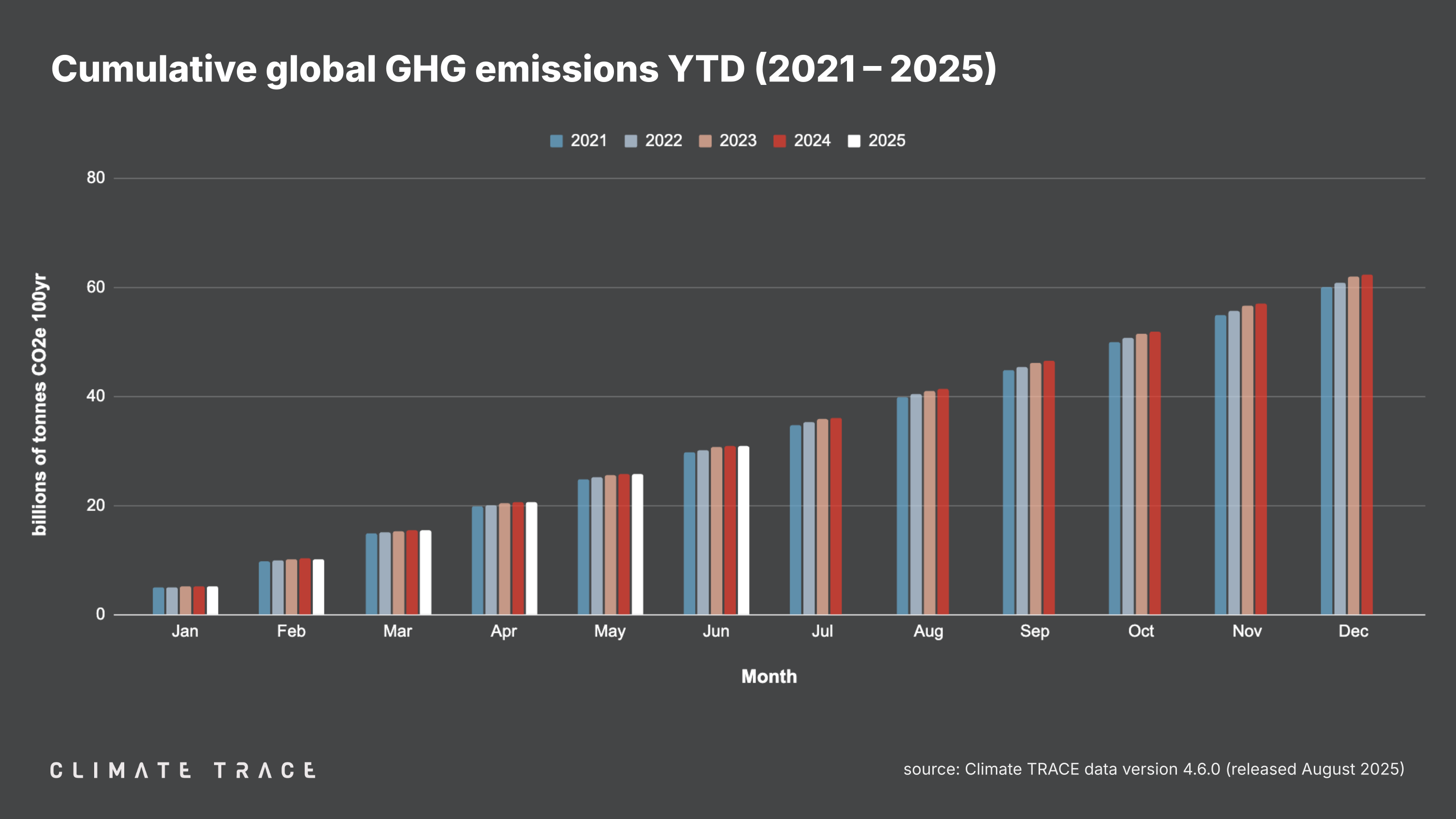

August 28, 2025 – Today, Climate TRACE reported that total global emissions in the first half of 2025 are 30.99 billion tonnes CO₂e. This is 0.13% higher than emissions were in the first half of 2024. Global greenhouse gas emissions for the month of June 2025 totaled 5.12 billion tonnes CO₂e. This represents an increase of 0.29% vs. June 2024. Global methane emissions in June 2025 were 34.82 million tonnes CH₄, an increase of 0.49% vs. June 2024.

Data tables summarizing emissions totals for June 2025 by sector, country, and top 100 urban areas are available for download here.

Lookback: Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions for the First Half of 2025

In the first half of 2025, the sector driving the most growth in emissions was fossil fuel operations, where emissions rose by 1.5% (an increase of 77.65 million tonnes of CO₂e). The United States accounted for more than half of that increase. Manufacturing emissions also rose in the first half of 2025, growing by 0.3% (an increase of 18.75 million tonnes of CO₂e), led by increases in India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Brazil.

Meanwhile, global power sector emissions saw the biggest decline in the first half of 2025, falling by 0.8% (a decrease of 60.27 million tonnes of CO₂e), driven almost entirely by declines in China and India, where power emissions were 1.7% lower and 0.8% lower than their totals in the first half of 2024, respectively.

The first half of 2025 shows small but positive progress on decarbonization in China, Mexico, and Australia. China’s emissions decreased 45.37 million tonnes CO₂e, or 0.51% compared to the first half of 2024. Mexico’s emissions decreased 7.78 million tonnes CO₂e, or 1.71% compared to the first half of 2024. Australia’s emissions decreased 6.56 million tonnes CO₂e, or 1.51% compared to the first half of 2024. However, some of the world’s other major emitting economies, including the United States, India, the EU, Indonesia, and Brazil, saw emissions rise in the first half of 2025.

– United States emissions increased by 48.57 million tonnes CO₂e, or 1.43% compared to the first half of 2024;

– India emissions increased by 4.44 million tonnes CO₂e, or 0.21% compared to the first half of 2024;

– European Union emissions increased by 2.90 million tonnes CO₂e, or 0.15% compared to the first half of 2024.

– Indonesia emissions increased by 3.06 million tonnes CO₂e, or 0.39% compared to the first half of 2024;

– Brazil emissions increased by 9.84 million tonnes CO₂e, or 1.24% compared to the first half of 2024.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Country: June 2025

Climate TRACE’s preliminary estimate of June 2025 emissions in China, the world’s top emitting country, is 1.46 billion tonnes CO₂e — an increase of 0.92 million tonnes of CO₂e or 0.06% vs. June 2024.

Of the other top five emitting countries:

– United States emissions increased by 4.89 million tonnes CO₂e, or 0.86% year over year;

– India emissions declined by 0.11 million tonnes CO₂e, or 0.03% year over year;

– Russia emissions increased by 0.95 million tonnes CO₂e, or 0.38% year over year;

– Indonesia emissions increased by 0.43 million tonnes CO₂e, or 0.33% year over year.

In the EU, which as a bloc would be the fourth largest source of emissions in June 2025, emissions declined by 1.80 million tonnes CO₂e compared to June 2024, or 0.58%.

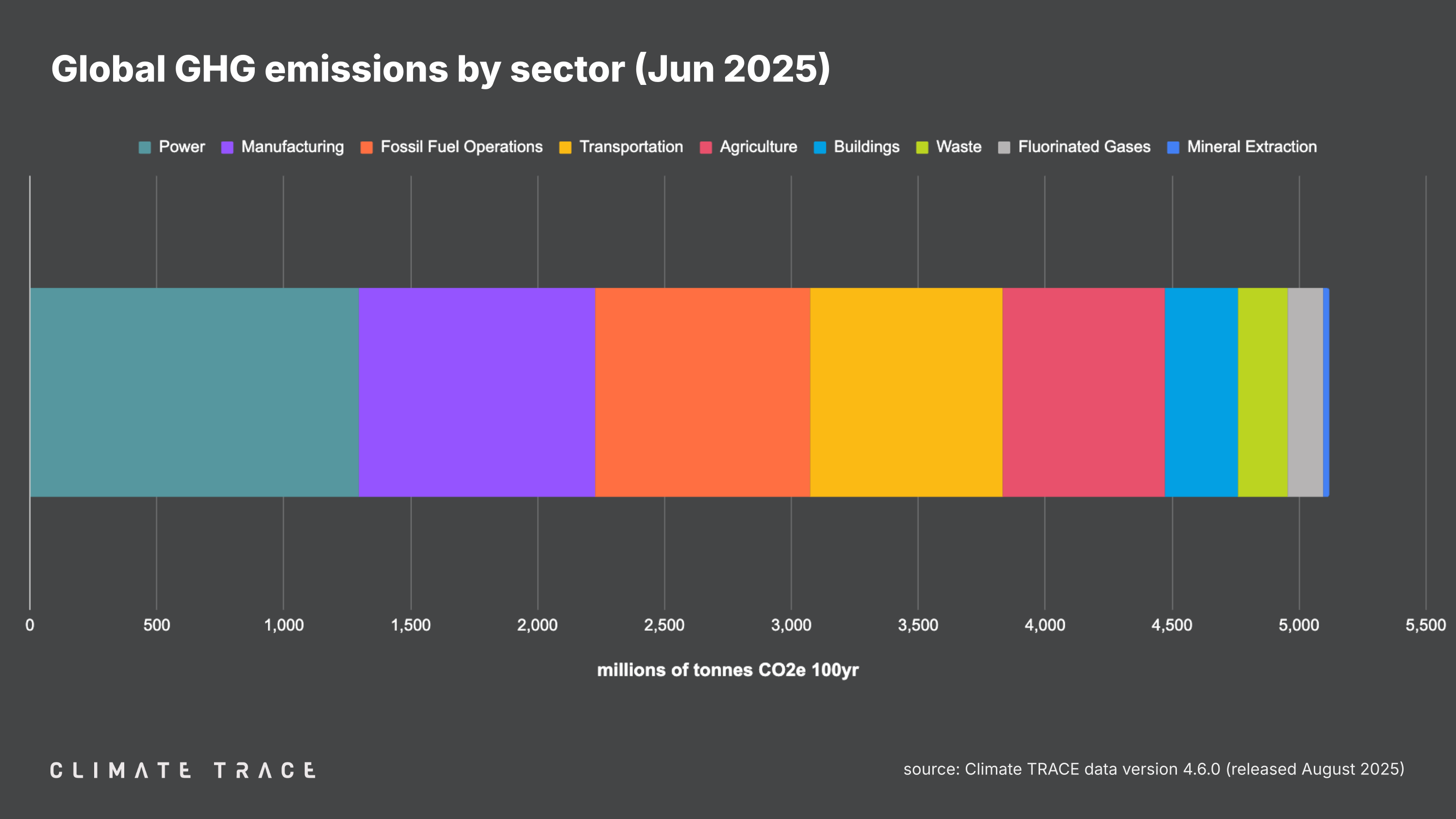

Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector: June 2025

Greenhouse gas emissions increased in June 2025 vs. June 2024 in fossil fuel operations, manufacturing, transportation, and waste, and decreased in power. Fossil fuel operations saw the greatest change in emissions year over year, with emissions increasing by 1.85% as compared to June 2024.

– Agriculture emissions were 641.40 million tonnes CO₂e, unchanged vs. June 2024;

– Buildings emissions were 285.59 million tonnes CO₂e, unchanged vs. June 2024;

– Fluorinated gases emissions were 137.71 million tonnes CO₂e, unchanged vs. June 2024;

– Fossil fuel operations emissions were 846.19 million tonnes CO₂e, a 1.85% increase vs. June 2024;

– Manufacturing emissions were 929.05 million tonnes CO₂e, a 0.02% increase vs. June 2024;

– Mineral extraction emissions were 23.22 million tonnes CO₂e, unchanged vs. June 2024;

– Power emissions were 1,297.34 million tonnes CO₂e, a 0.56% decrease vs. June 2024;

– Transportation emissions were 759.10 million tonnes CO₂e, a 0.77% increase vs. June 2024;

– Waste emissions were 197.77 million tonnes CO₂e, a 0.26% increase vs. June 2024.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions by City: June 2025

The urban areas with the highest total greenhouse gas emissions in June 2025 were Shanghai, China; Tokyo, Japan; New York, United States; Houston, United States; and Los Angeles, United States.

The urban areas with the greatest increase in absolute emissions in June 2025 as compared to June 2024 were Pittsburgh, United States; Xinyu, China; Tokyo, Japan; Baotou, China; and Algeciras, Spain. Those with the largest absolute emissions decline between this June and last June were Leipzig, Germany; Anqing, China; Duren, Germany; Houston, United States; and Anchorage, United States.

The urban areas with the greatest increase in emissions as a percentage of their total emissions were Kombissiri, Burkina Faso; Gambat, Pakistan; Bitilta Zebraro, Ethiopia; UNNAMED, Sudan; and Oviedo, Spain. Those with the greatest decrease by percentage were Leipzig, Germany; Duren, Germany; Wolfsburg, Germany; Atebubu, Ghana; and Evansville, United States.

RELEASE NOTES

Revisions to existing Climate TRACE data are common and expected. They allow us to take the most up-to-date and accurate information into account. As new information becomes available, Climate TRACE will update its emissions totals (potentially including historical estimates) to reflect new data inputs, methodologies, and revisions.

With the addition of June 2025 data, the Climate TRACE database is now updated to version V4.6.0. This release incorporates the most recent FAOSTAT and CEDS data in applicable sectors. The release also reflects updated methodology for non-GHG emissions from glass, cement, and lime production; the addition of N2O emissions across agriculture subsectors and additional refinements to agriculture emissions factors; updated North America and Europe data for Q4 2024 in petrochemicals and oil and gas refining; updated methodology and data for cement and steel production to reflect updated emissions factors; and the addition of 56 steel plants to our database.

A detailed description of data updates is available in our changelog here.

To learn more about what is included in our monthly data releases and for frequently asked questions, click here. All methodologies for Climate TRACE data estimates are available to view and download here. For any further technical questions about data updates, please contact: coalition@ClimateTRACE.org.

To sign up for monthly updates from Climate TRACE, click here.

Emissions data for July 2025 are scheduled for release on September 25, 2025.

About Climate TRACE

The Climate TRACE coalition was formed by a group of AI specialists, data scientists, researchers, and nongovernmental organizations. Current members include Carbon Yield; CTrees; Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Energy, Environment & Sustainability; Earth Genome; Former Vice President Al Gore; Global Energy Monitor; Hypervine.io; Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab; OceanMind; RMI; TransitionZero; and WattTime. Climate TRACE is also supported by more than 100 other contributing organizations and researchers, including key data and analysis contributors: Arboretica, Carnegie Mellon University’s CREATE Lab, Global Fishing Watch/emLab, Michigan State University, Open Supply Hub, and University of Malaysia Terengganu. For more information about the coalition and a list of contributors, click here.

Media Contacts

Fae Jencks and Nikki Arnone for Climate TRACE

Glassmaking has dramatically evolved in the thousands of years since ancient artisans crafted their first decorative beads and perfume bottles. But the underlying recipe remains virtually the same: Combine sand, sodium carbonate, and limestone, then blast the ingredients with scorching heat in a kiln or furnace.

Today, the vast majority of that heat is supplied by burning fossil fuels. Whether manufacturers are turning glass into windows, beverage bottles, smartphone screens, or coatings for solar panels, their methods require lots of energy to reach superhigh temperatures and, as a result, can be very carbon-intensive.

Global glassmakers in recent years have begun working to curb their emissions, spurred by environmental laws and the growing demand for low-carbon products. Companies are testing and deploying new furnace technologies that get their heat from electricity — not fossil gas or heating oil — or from alternative fuels such as hydrogen and biogas.

The latest of these emerging efforts comes from Bavaria, Germany, where the multinational firm Schott recently began building a large-scale electric melting tank inside its existing plant in Mitterteich. The tank is the first of its kind for the type and amount of glass it’s making, and it will run primarily on renewable energy sourced from the grid to turn materials into molten glass.

Schott says its electric tank could slash greenhouse gas emissions from the melting process alone by 80% owing to the reduction in fossil gas use. The 40-million-euro ($47 million) pilot tank is expected to fire up in early 2027 and will produce specially engineered glass tubing for syringes, vials, and other pharmaceutical products.

Jonas Spitra, Schott’s head of sustainability communications, said that replacing fossil fuels with electrified technology — while still meeting strict quality requirements for specialty glass — marks “one of the most challenging yet decisive steps on the industry’s path to decarbonization.”

Schott, which operates in over 30 countries, will use the experiences from its all-electric tank initiative “as a foundation for expanding electrification to other sites, wherever technically and economically feasible,” he told Canary Media.

The German pilot project is moving forward just as a few ambitious low-carbon glass initiatives in the United States have fallen into limbo. In May, the Trump administration’s Department of Energy canceled awards worth roughly $177 million for projects aiming to demonstrate cleaner glassmaking methods in California and Ohio, forcing manufacturers to reevaluate their plans.

“Domestic glass manufacturers across the country are advancing energy-efficient technologies, reducing emissions, and working to try and keep jobs onshore,” Scott DeFife, president of the Glass Packaging Institute, said in a June 6 statement in response to the DOE’s decision. “The Department should lean into glass, not ignore it.”

Worldwide, manufacturers made more than 150 million metric tons of glass in total in 2022. Although glass is used across many sectors, it is produced on a smaller scale than other carbon-intensive materials. Cement production, for instance, surpassed 4 billion metric tons in 2023, while steel production reached nearly 2 billion metric tons that year.

Still, glassmaking remains a significant source of planet-warming gases and local air pollutants like nitrogen oxides. And the challenge of slashing those emissions is essentially the same one vexing other heavy industries: figuring out how to reach hot enough temperatures to make materials without cooking the planet in the process.

Chemical producers are pilot-testing their own electric furnaces to make important compounds like ethylene, which is the building block of many plastic products. Cement startups are developing electricity-driven processes and thermal storage systems to replace traditional kilns. Global steelmakers, meanwhile, are investing in technologies that sidestep the need to use coal, such as hydrogen-based ironmaking facilities and electric arc furnaces.

For glass, the biggest hurdle to decarbonization lies in the melting process, Schott’s Spitra explained.

Glass furnaces require temperatures of between 1,200 and 1,700 degrees Celsius (2,192 and 3,092 degrees Fahrenheit) — hotter than lava — to liquefy the raw materials and mix in recycled glass. The process is responsible for about two-thirds of total carbon dioxide emissions from glass production. Most of that CO2 comes from burning fossil fuels, though some emissions result from the chemical reactions that happen when heating up sodium carbonate (soda ash) and limestone.

In a conventional furnace, gas is injected into a combustion chamber to melt the ingredients into a glowing orange liquid. In an electric version, electrodes pass currents through a conductor to generate heat. Today, the industry mostly uses electric equipment only for smaller-scale furnaces or to supplement the fossil-fuel-based heat inside larger furnaces — a step known as “electric boosting.”

Facilities that make high-volume products like container glass and windows are trickier to fully electrify. Existing electric designs have struggled to operate with the same consistency and flexibility as gas furnaces, and they can’t incorporate as much recycled material into the glass mix. Electric furnaces also tend to wear down and need replacing about twice as fast as their gas-burning counterparts, according to glass industry experts.

In Germany, Schott is aiming to address those problems with its new industrial-scale melting tank, which must also meet the exacting standards for bubble-free, high-quality pharmaceutical glass. The initiative, which Schott began developing in 2021, is partly funded by the German government and a European Union–backed program to decarbonize energy-intensive industries in Germany.

The company is investing in electrification in part to meet European climate regulations, including a CO2 emissions cap for heavy industrial sectors. But it’s also responding to the demand from pharmaceutical customers that are working to reduce their supply-chain emissions. Schott views decarbonization as a “strategic opportunity to strengthen its competitiveness,” Spitra said.

Beyond the technical issues, a few other barriers stand in the way of electrifying glassmaking at a wider scale.

In some locations, the local grid may be unable to support a major increase in electricity use, requiring companies and utilities to upgrade that infrastructure or build more wind, solar, and other electricity resources. For producers of mass-market packaging like soda bottles, it can be harder to convince beverage companies to pay more for low-carbon glass if it means raising the sticker price of the final product, especially if the competition is cheap plastic containers.

Another challenge for U.S. glassmakers in particular is that switching to electricity very likely means paying higher utility bills, making it harder to justify ditching fossil gas.

Sonya Pump, the global sustainability director for Ohio-based O-I Glass, said that gas pricing is one of the key factors the company weighs when evaluating low-carbon furnace technologies — along with potential technical constraints or risks to its manufacturing capabilities. O-I Glass makes billions of glass containers every year in facilities in nearly 20 countries, and the criteria it considers vary by market, as well as the type and quantity of glass it’s producing.

For that reason, in the U.S., “a fully electric melter is not currently the best solution for our business,” she said. “Though, in other geographies — areas in Europe, for example — energy pricing, carbon costs, and intense interest from our customers in emerging sustainability solutions make for analyses that look very different.”

In central France, O-I Glass is investing $65 million to build a hybrid-electric melter that can use up to 70% electricity and is set to come online in 2026. Pump said her team is also learning from its participation in electrification projects conducted through the nonprofit consortium Glass Futures and from other industry efforts. At the same time, O-I Glass is replacing some of its older furnaces in the U.S. and globally with modern systems that use oxygen and waste heat to reduce facilities’ total fossil-fuel use.

The manufacturer recently set a goal of slashing its overall greenhouse gas emissions by 47% by 2030, relative to 2019 levels, in addition to boosting its use of electricity from renewables and increasing the use of recycled glass.

O-I Glass had planned to rebuild an aging furnace in Zanesville, Ohio, and combine five cutting-edge technologies — including for electric boosting, preheating materials, and recovering waste heat — to see how much they could offset gas consumption when working together. The project was slated to receive up to $57.3 million from the DOE. Now that the federal funding has been canceled, the company is considering its next steps, Pump said.

Other initiatives to electrify glassmaking or test replacing gas with hydrogen are also now “slightly paused” under the Trump administration, said Matthew Kirian, director and technical program manager of the Northwest Ohio Innovation Consortium. The nonprofit works with O-I Glass and other manufacturers such as solar-panel-maker First Solar to advance innovation within the region’s long-standing glass industry.

“On the energy and fuel side of things, it’s hard to set a firm strategy, especially for the next two to three years, because of federal policy that is so clear … that combustion is king,” Kirian said.

For now, he added, glass manufacturers are largely focusing on other strategies to lessen their environmental impact, including improving the energy efficiency and operating performance of existing facilities and working to increase recycling rates for glass containers — only about 30% of which get recycled nationwide — so that less material winds up in landfills and more is melted into fresh glass.

“Their sustainability goals aren’t going away,” Kirian said of the glassmakers. “We’re hoping to really move the needle for generations to come.”