Headlines often paint a picture that America’s energy transition is off track, suggesting that the U.S. is no longer an attractive market for energy project investment.

But DNV’s Energy Transition Outlook and Energy Industry Insights surveys tell a different story, revealing unique perspectives from business leaders involved in North American energy projects.

Enduring optimism:

Business leaders remain confident in a long-term future for a decarbonized energy system. The coming years will see a renewed focus on an all-inclusive approach to how energy is produced, moved, stored, and used.

Pace of change:

The energy transition is seen as slowing, not stopping. Policy shifts and global geopolitical tensions impacting supply chains are the main factors contributing to the slowdown.

“All of the above” solutions:

North America needs more of all forms of energy production to meet growing demand. This includes projects that combine fossil fuels and renewables.

Grid modernization:

Urgent investment in the grid is needed. Connecting renewables, managing distributed energy resources, and meeting demand will be impossible without modernized transmission.

Smarter energy use:

Across America, consumers are reshaping the energy system by converting their homes and businesses into mini power plants featuring rooftop solar, electric vehicles, and battery storage. Advanced digital technology can use these distributed energy resources to help balance the grid.

The answer is yes — if the solutions are as broad as possible.

America needs an “all of the above” approach to meet the increasing demand for energy. The key is to think in systems, not in silos. This means an interconnected energy system that puts everything on the table — solar, wind, oil and natural gas, low-carbon and renewable products, battery storage, energy efficiency, virtual power plants (VPPs), and carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) can all contribute to a reliable, lower-carbon, and affordable energy transition.

In our 2023 Energy Transition Outlook for North America, we estimated a $12 trillion opportunity. Things have changed. Today, DNV continues to see the energy transition in the U.S. and Canada offering significant financial opportunities. However, the size of the prize is different, as regional policy shifts, ongoing geopolitical tensions, and supply chain issues have affected the economics and pace of delivering energy projects.

We will explore this in-depth in our upcoming 2025 Energy Transition Outlook for North America report, but as a preview, here are a few key insights for the major players:

Renewable developers:

Pairing renewable power generation, battery storage, and natural gas–fired power generation is an attractive opportunity to use existing infrastructure to bring lower-emission energy online faster and more affordably.

Utilities:

Virtual power Plants (VPPs) offer a way to reduce peak demand, cut energy bills, make it easier to bring more renewable power online, and — critically — boost energy efficiency.

Investors:

Financing structures are evolving as North America pursues an “all of the above” approach to energy and infrastructure creates exciting opportunities for divestment and opportunities of assets.

Oil and gas companies:

Fossil fuels — especially natural gas — will continue to play a role in the energy mix. Decarbonizing fossil fuel production with low-emission hydrogen and carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), while blending in renewable feedstock, is critical.

Even as incentives are phased out, market forces are making solar and solar-plus- storage projects the optimal choice for new power generation. But solar isn’t the only option. Here’s what winning companies will act now to invest in:

• Energy efficiency

• Energy storage

• Hybrid power generation

• Fossil fuel decarbonization

• Digital trust

For more than 125 years, DNV has helped businesses progress winning energy projects in the US and Canada that contribute to energy security, affordability, and reliability. DNV helps clients confidently navigate complex projects and ensure they are bankable and successful.

DNV’s proven impact

Energy efficiency:

DNV has delivered over 2 million megawatt-hours and 40 million therms in energy savings, significantly reducing costs and emissions for utilities and millions of users.

Clean energy capacity:

DNV supported 400 gigawatts of clean energy capacity and oversaw more than $1 billion in energy spending, accelerating renewable deployment and grid modernization.

Oil and gas:

DNV has a long history of supporting safe oil and gas operations. The vast majority of oil and gas pipelines are built to our standards, and we lead the industry in validating the materials used in technologies essential for offshore oil and gas development.

Research and technology centers:

We operate state-of-the-art technology centers and testing facilities around the world. At these facilities, dedicated experts research and develop solutions for some of the most challenging issues facing the energy sector.

Advanced digital solutions:

We are a world-leading provider of software and digital solutions for managing risk and improving performance of power generation assets, transmission lines, pipelines, processing plants, offshore structures, ships, and more.

Your partner for energy systems thinking

DNV ensures integrated planning across all energy types, sectors, and regions. DNV’s North American team deeply understands the entire energy system, including specific regional markets and regulatory frameworks. This local expertise is powerfully backed by a global network of experts, ready to be mobilized anywhere in the world, with access to world-class technology centers and cutting-edge digital tools.

Learn more in the Global Energy Transition Outlook 2025 report.

A new policy in China could ramp up the nation’s production of green hydrogen for use in airplanes, ships, and other heavy industries, potentially eclipsing output of the fuel in the United States and Europe.

Earlier this month, the National Development and Reform Commission — the high-ranking executive department in charge of economic planning — released what analyst Jian Wu called China’s single “most important low-carbon policy for 2025.”

Until now, China has encouraged provincial governments and state-owned companies to develop hydrogen technology by providing lower electricity prices and loans and by setting production quotas. But unlike the United States and the European Union, the national government in Beijing had no overarching policy to directly subsidize low-carbon hydrogen projects.

While the document published on Oct. 15 does not specify hydrogen by name, the policy change makes Chinese industries that depend on the clean fuel eligible for direct grants.

For the first time ever, the rules outlining which types of industrial projects qualify for national grants list green methanol, carbon capture, sustainable aviation fuel, and zero-carbon industry parks — “paving the way for rapid development of these applications in China,” Wu wrote in his China Hydrogen Bulletin newsletter. Of the hundreds of clean-energy directives China issues at its various levels of government each year, Wu emphasized, the latest policy is “absolutely” the most significant, particularly for heavy industry.

By designating those sectors for direct grants under Beijing’s central budget, “the government is effectively establishing its first national funding mechanism for some of these hydrogen-adjacent technologies,” said Amy Ouyang, a hydrogen associate at the Clean Air Task Force, a Boston-based environmental group.

“China’s hydrogen sector has relied heavily on private capital, so this guidance marks a potential shift toward a more coordinated, state-backed effort to turn policy ambition into on-the-ground deployment,” she said, adding that “the inclusion of these adjacent technologies could reinforce its growing role in China’s broader industrial decarbonization strategy.”

The move comes as the United States turns away from its nascent efforts to develop a clean-hydrogen industry. The landmark 45V federal tax credits meant to spur production and use of clean hydrogen, once slated to last until 2033, are now set to phase out in two years as a result of President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act. The Trump administration, meanwhile, is poised to use funding meant for hydrogen-based steel projects to bolster production of steel made with fossil fuels instead.

China is already the world’s largest hydrogen market, by far. At about 33 million metric tons of demand per year, the industry is roughly three times the size of the American market. In the United States, 95% of hydrogen is produced with natural gas, primarily through a process that involves using steam heated to temperatures as high as 1,832 degrees Fahrenheit to separate the molecule out of methane. America’s reliance on natural gas is no surprise, given that it has vast reserves and the world’s largest drilling industry.

By contrast, China imports much of its natural gas, so the fuel is used to generate 25% of the country’s hydrogen. A significant share of China’s hydrogen is a byproduct of other industrial processes, such as heating coal to make purified “coke” for steel mills.

Since a portion of that byproduct hydrogen is vented into the atmosphere as waste, the new national grants could include projects that capture and repurpose more of that gas. But China’s world-leading deployments of solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear power plants also generate an ample supply of clean electricity to produce green hydrogen — the version of the fuel made by blasting distilled water with enough electricity to separate hydrogen molecules from the oxygen ones. Already, in July, China agreed to sell a historic debut shipment of green steel made with hydrogen to buyers in Italy.

Despite China’s clean-energy advantage, the U.S. and European Union had, until now, boasted stronger national policies for developing domestic green hydrogen.

While China’s government-owned businesses invested in green hydrogen, “there was nothing at the national level,” like the 45V tax credits in America’s Inflation Reduction Act or the European hydrogen bank, said Anne-Sophie Corbeau, a hydrogen researcher at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

For example, Beijing backed fuel-cell vehicles, but the support came primarily as a reward for reaching manufacturing targets, not as direct subsidies, she said. The central government might give an annual reward of 1.6 billion yuan ($225 million) per city based on progress toward certain deployments of fuel-cell infrastructure, but “if you are underperforming, you may get nothing,” Corbeau said.

“Broadly, that means no state support for industrial applications like what we may have seen in other countries,” she said.

This month’s policy shift will direct Beijing’s funding hose at heavy industries that transition from coal and gas to hydrogen, including “power, steel, nonferrous metals, building materials, petrochemicals, chemicals, and machinery,” said Xinyi Shen, the China team lead at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, a Finnish research nonprofit.

“This policy sends a strong signal of China’s commitment to accelerating its green transition,” she said. “Given China’s current clean-energy momentum and industrial policy direction, the country may ultimately achieve deeper [emissions] cuts than it has formally committed to.”

Still, Shen warned, “green hydrogen remains costly.” But China’s capacity to swiftly scale industries that the government makes a priority has a history of sending prices plunging, as happened with solar panels and batteries. And China’s hydrogen sector “is expanding rapidly,” Ouyang said.

Between 2021 and 2023, she said, roughly 100 to 200 new hydrogen-related companies launched each year in the country. Today, China dominates manufacturing of the most popular type of electrolyzer, the machine used to make green hydrogen, representing roughly 60% of the global market. Thanks to that scale, a Western company buying a Chinese-made electrolyzer would pay one-third the price of a locally made counterpart.

If central government funding accelerates in the next year or two as expected, “China could solidify its leadership in the industry and achieve some of the world’s lowest-cost green hydrogen,” Ouyang said.

That could put the U.S. and Europe at risk of lagging behind China, just as they have with other steps in the clean-energy supply chain, experts say.

Corbeau said the conditions are already there for China to dominate the industry. Once the federal tax credits expire, she said, “nothing much will happen” beyond “a few projects” in America.

She noted that in Europe earlier this year, the regional hydrogen bank’s second offering of a public subsidy for hydrogen tried to limit funding for projects that had too many Chinese components. But “the scheme does not give much money, and some projects told me they are better off with Chinese technology because of the cost advantage,” Corbeau said.

“It’s almost too late already,” she added.

Maine and Connecticut are considering working together to build renewable-energy projects faster, a strategy that could be repeated throughout the region as states with ambitious emissions-reduction goals race to take advantage of federal tax credits before they disappear.

“They’re trying to collaborate, trying to coordinate,” said Francis Pullaro, president of clean-energy trade association Renew Northeast. “This is a preview of what’s to come.”

The next eight months are crucial for commercial-scale clean-energy developments nationwide. The tax credits included in former President Joe Biden’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act spurred massive investment in the sector, with more than $360 billion in projects already announced as of June 2024. Now the Trump administration is phasing out the incentives for wind and solar farms, requiring them to begin construction by July 4, 2026, or be placed in service by the end of 2027 in order to qualify for the tax credits. Across the country, states are responding by streamlining permitting processes and fast-tracking clean-energy procurements to get projects going in time.

Maine and Connecticut — which both aim to get all of their power from clean sources by 2040 — have been among the states looking for ways to get projects in under the deadline. In July, Maine asked for proposals for up to 1,600 gigawatt-hours of renewable energy, giving developers just two weeks to submit their bids; regulators selected one hydropower and four solar developments in September.

It was Connecticut’s call for collaborators that sparked the emerging partnership between the states.

Connecticut released a request for proposals for solar and onshore wind projects in September, with a deadline of Oct. 10. The initial timeline calls for bids to be selected in November, and final contracts to be submitted by the end of the year. The call for proposals included provisions to allow other states to participate. Each state would make its own evaluations; if another state decided to select a project, it would coordinate with Connecticut on finalizing the terms of the deal.

Maine’s newly created Department of Energy Resources saw potential in this opportunity and reached out to the state’s utility commission, which voted to join Connecticut’s procurement. This move does not mean Maine will necessarily choose the same projects as its New England neighbor, just that it will have the opportunity to assess the same bids against its own criteria and needs.

The hope is that, by pooling demand and sharing information, both states will emerge with more efficient and viable projects at lower prices for residents.

“It makes a lot of sense for a state like Maine to piggyback on their efforts and hopefully enter into contracts for a share of the capacity that gets bid in cost-effectively,” said Jamie Dickerson, senior director of climate and clean-energy programs at Acadia Center, an advocacy group.

Both Connecticut and Maine have previously attempted to collaborate with other states on renewable-energy procurements, though not on quite as tight a timeline.

In 2022, Massachusetts agreed to buy 40% of the power produced by a planned onshore wind farm in northern Maine, though that development stalled when a deal for an associated transmission line fell through. In 2023, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island announced a three-state offshore wind solicitation; in the end, Connecticut declined to choose any of the bidders, although the two other participating states contracted nearly 2.9 GW of capacity.

Whether this latest endeavor yields any joint procurements remains to be seen, but Pullaro is confident that it will not be the last cooperative effort among New England states as the tax-credit deadline looms.

“The states are having a lot of conversations,” he said.

It’s a known problem that onshore wind turbines kill bats. But it’s unclear whether the same issue applies to offshore wind installations — and the Trump administration just canceled groundbreaking research into the question.

Earlier this month, the nonprofit Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) received a letter from the Department of Energy abruptly canceling its $1.6 million grant to study bat behavior in California waters earmarked for offshore wind development — a move that will hinder the nascent research effort. Christian Newman, EPRI’s program manager for the grant, said the organization is actively looking for other funding sources.

The researchers had been two years into a study of bats in the territory California plans to dot with floating offshore wind turbines over the coming decades. There’s so little information about how North American bats use the ocean environment that, in 2021, Newman and his colleagues determined in a peer-reviewed study that predicting the number of bats potentially killed by U.S. offshore wind development was “impossible” — at least until more data rolled in.

The bat project is one of 351 individual Energy Department awards, totalling nearly $16 billion in funding, that in early October appeared on a leaked list of potential grant terminations. News reports have since verified the cancellations of some awards on that list, including more than $700 million for batteries and manufacturing, according to Politico’s E&E News. The cancellation of EPRI’s bat research grant has not previously been reported.

The news comes as the Trump administration defunds other research investigating offshore wind’s impact on wildlife. In recent weeks, the Interior Department scuttled two programs, totalling over $5 million, that were actively monitoring the movement of whales in East Coast waters where five commercial-scale wind projects are currently being built.

The West Coast bat study, awarded federal funding in 2022, supported researchers from multiple organizations, including Bat Conservation International. The U.S.-based conservation group has been at the forefront of bat and wind-energy research for over two decades. Until recently, almost all of that work was devoted to onshore wind turbines.

“Wind energy is a really important component of our global energy transition. Unfortunately, wind turbines kill millions of bats globally every year,” said Winifred Frick, chief scientist at Bat Conservation International.

She contributed to a study last year that estimated onshore wind farms killed nearly 800,000 bats every year in just four countries that took annual tallies — Canada, Germany, the U.K., and the U.S.

It’s logical to expect fewer bat deaths might result from wind turbines spinning out in the ocean compared to ones operating on land. After all, according to Frick, even scientists like herself assumed that most species simply do not spend much time at sea.

But, at least on the West Coast, researchers had never scientifically checked. In fact, EPRI was collecting first-of-its-kind information on how the Mexican free-tailed bat interacts with the ocean, deepening scientists’ understanding of the species overall. The EPRI team detected the bats vocalizing while flying over a dozen miles off the coast of Southern California last year, thanks to an acoustic listening device attached to a small sailing drone they launched. Before this study, no one knew that this common and widespread species spent any time at sea.

“One of the things that we’re learning is that there are more bats flying out in the [ocean] environment than we might have otherwise expected,” said Frick.

And that means more bat species are potentially threatened by California’s future offshore turbines than previously thought. Frick added that a greater understanding of which species spend time at sea and when can inform the design of solutions that better minimize fatalities from wind farms.

One solution is called curtailment. Frick described this approach as changing the “cut-in speed,” which is the minimum wind speed at which operators allow turbine blades to begin spinning at certain times of day or year.

The modification does not typically lead to significant changes in energy generation for onshore wind farms but can make a big difference for bats, she said. For example, preventing turbine blades from spinning until the wind reaches 5 meters per second can reduce fatalities among many species by 62% on average, according to a study released last year by Frick and her colleagues.

Determining the best curtailment solutions for offshore wind turbines and North American bat species is still a work in progress. Energy Department-funded studies, like the EPRI effort, were seen as critical to determining which bat-saving modifications would work best for California’s unique vision to build floating turbines.

Frick called the grant’s termination “devastating” because the team may not get to finish the study. In the meantime, researchers are retrieving bat listening devices from spots along the West Coast.

Bat Conservation International continues its efforts to minimize bat deaths from turbines on land. It received a $2.4 million grant from the Energy Department last year to assess how new technology might help. That award also appeared on the leaked list of 351 DOE projects seemingly slated for cancellation. But, according to Frick, the federal government has yet to cut that research — “it’s not officially terminated” — and she remains optimistic that it might endure.

A clarification was made on Oct. 31, 2025: This story has been updated to more precisely reflect Christian Newman’s statements regarding the cancellation of EPRI’s award.

While the federal policy and regulatory landscapes in 2025 are, to put it mildly, full of uncertainty and outright antagonism — from the cancellation of programs like Solar for All to the rapid drawdown or outright elimination of the Inflation Reduction Act’s incentives for technologies like solar, storage, wind, and electric vehicles — the choice for the industry is either to wait and hope for better political tides in Washington or to adapt and fight to meet the moment.

“It is very easy to get overwhelmed by this moment,” said Amisha Rai, senior vice president of advocacy at Advanced Energy United (United), an industry association representing many of the leading solar, wind, storage, and demand and distributed energy companies. “You could go into the zone of just being flustered and become part of that chaos. Or you can figure out a construct where you can continue leading and focus on a solutions-oriented path.”

The choice for Rai and United was simple. Founded in the aftermath of the 2010 failure of the federal Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill, United was built from the start to engage deeply with state policymakers and regional regulators to educate them about the benefits that advanced energy technologies can deliver to citizens and the grid.

United has achieved a long list of legislative and regulatory achievements over its decade-plus of state and regional engagement. Most recently, United championed California’s passage of the “Pathways Initiative” bill, which grants the state’s independent system operator authority to collaborate with other Western states to create an entirely new day-ahead energy trading market for the Western region — a move that is expected to bolster clean energy deployment and save participants upwards of $1.2 billion annually.

Meeting the moment with practical, available solutions

Despite the headwinds from the nation’s capital, United continues to make progress for the industry in state capitals. Recently, the association leveraged its deep experience to develop a playbook that the entire industry can use to further this progress. “The playbook is a way to organize the solutions available to decision-makers and a guide to leaders of any political stripe and in any state about how to think about the urgent challenges they face today,” Rai said.

The challenges are significant. Electricity demand is projected to surge in coming years, driven by data centers, artificial intelligence, electrification, and industrial reshoring. At the same time, energy costs are spiking, supply chain constraints and tariffs are slowing energy infrastructure development, and extreme weather events are straining grid resilience.

State leaders find themselves caught between rising and understandable citizen concerns about energy costs and the urgent need to meet explosive load growth while maintaining grid reliability. Unlike hyperpartisan Washington, state capitals remain a venue for problem-solving. “We have had these conversations with lawmakers that are across the map — rural, urban, Republican, Democrat, Independent,” Rai explained. “The beauty of this playbook is it applies in Texas, and it applies in Pennsylvania, California, Indiana, or Virginia.”

State and local decision-makers understand that they are accountable to constituents who expect the lights to stay on and bills to remain affordable. The advanced energy technologies available today — from large-scale solar, wind, and storage to distributed resources like virtual power plants and advanced efficiency innovations such as smart thermostats and building energy management systems — offer immediate, deployable solutions. Unlike new gas plants and pipelines that take years to build and also risk becoming stranded assets, these technologies can be deployed quickly to meet urgent reliability needs while containing costs.

A three-pillar framework for action

United’s playbook organizes solutions around three core objectives that address the full spectrum of state energy challenges:

Build it: To meet projected load growth, states can accelerate deployment of least-cost energy projects by reforming generation and transmission development processes. This includes streamlining planning, siting, permitting, interconnection, and procurement procedures to build a stable pipeline of projects that will meet growing future residential, business, and industrial needs.

California’s Pathways Initiative exemplifies this approach. The landmark legislation, nearly a decade in the making, enables Western states with vastly different energy portfolios to work together on market expansion, making it easier to boost transmission capacity, get more clean energy projects connected to the grid, and create efficiencies that will benefit affordability and reliability across the region.

United has also been working on improving energy markets in other parts of the country. For instance, the organization has been leading efforts to have PJM Interconnection — the nation’s largest grid operator, serving 13 states and D.C. — make significant reforms to address the massive backlog of projects waiting to connect to its grid, a critical bottleneck preventing clean energy deployment and keeping prices sky high. These regional efforts complement the statewide developments in siting and permitting legislation that United recently helped secure in Michigan and Massachusetts.

Make it flexible: States can maximize existing grid infrastructure by scaling up distributed energy resources, energy waste reduction, virtual power plants, and advanced vehicle and building electrification solutions through state-led programs, plans, and rates. These technologies help grid operators manage costs in real time while preparing the system for increased demand.

Following Winter Storm Uri’s devastating blackouts in 2021, state leaders in Texas recognized the value of flexibility, energy waste reduction, and consumer participation. Recent legislation in Texas has expanded opportunities for those demand-side programs to help shore up the grid. “Texas has showcased that these resources can actually keep the lights on and help strengthen the grid system,” Rai said. “We don’t need to wait 20 years to solve all of our problems. These are solutions that can actually be deployed immediately.”

“We don’t need to wait 20 years to solve all of our problems. These are solutions that can actually be deployed immediately.”

- Amisha Rai, Advanced Energy United

Make it affordable: States can ensure public utilities are planning, optimizing, and delivering the right types of energy investment at the lowest possible cost while identifying least-cost financing avenues for projects both big and small. This includes avoiding investments in infrastructure that may become a stranded asset.

Colorado leads the way in comprehensive energy system planning. The state has implemented country-leading electric distribution system planning that accounts for how distributed resources can play an increasing role in grid reliability, and Colorado has one of the strongest frameworks for containing costs on the gas pipeline system. As a result, the state’s utility regulators are currently reviewing a proposal to save Coloradans $150 million by investing in efficiency, electrification, demand flexibility, and a small liquefied natural gas facility instead of the traditional gas-only solution.

A path forward

The United playbook recognizes a fundamental truth: There is no single answer to America’s energy challenges. The energy system is complex and interconnected, and decision-makers must assess how different technologies combine to keep prices low, secure the economic opportunities represented by data centers and AI, and ensure a resilient and reliable grid.

States are the best place for action and progress, in large part because so much of energy policy lives at legislatures and state agencies. “The urgency right now is making sure that state leaders have a path for action and are not stuck in the chaos and noise of the moment,” Rai said. “This playbook provides a constructive path that works despite the chaos people are seeing at the federal level — a focus on action, not just talk.”

If you thought the world built a lot of renewables in the past few years, just wait for the next half of this decade.

Between 2025 and 2030, the world is expected to build nearly 4,600 gigawatts — or 4.6 terawatts, if you please — of clean power, according to a new report from the International Energy Agency.

That’s nearly double the amount built over the previous five-year period, which was in turn more than double the amount built across the five years before that. Put differently, the growth has essentially been exponential.

Solar is the driving force behind this expansion, which is key to transitioning the world away from planet-warming fossil fuels. It accounts for more than three-quarters of the expected increase in renewables between 2025 and 2030 — the result, IEA says, of not only low equipment costs but also solid permitting rules and a broad social acceptance of the tech.

This solar boom will be almost equally split between utility-scale installations and distributed projects, meaning panels atop roofs or shade structures in parking lots, for example. Just over 2 TW of large-scale projects will be built compared to 1.5 TW of the smaller, distributed stuff, IEA predicts. The latter category is increasingly popular both in countries with rising electricity rates and in places with unreliable grids, like Pakistan, where residents are taking refuge in the affordable and stable nature of the tech.

China is installing most of the world’s solar, but the technology is a global phenomenon at this point. At least 29 countries now get over 10% of their electricity from the clean energy source, per a separate report released by think tank Ember earlier this month.

Other types of clean energy are set to grow, too, just not at anything close to solar’s scale.

Installations of onshore wind will leap from 505 GW over the previous five-year period to 732 GW between 2025 and 2030. Offshore wind will more than double from 60 GW to 140 GW. Hydropower will rebound modestly from a down couple of years, but still won’t expand at the levels seen in the early to mid-2010s.

Still, renewables are not gaining enough ground to triple clean capacity by the end of this decade compared with 2023 — a goal countries around the world set two years ago at COP28, the annual United Nations climate conference. In just a few weeks, global leaders will reconvene in Brazil for COP30. The IEA figures, while a sure sign of progress, underscore the steep climb ahead.

The Trump administration has repeatedly blamed offshore wind farms for whale deaths, contrary to scientific evidence. Now the administration is quietly abandoning key research programs meant to protect marine mammals living in an increasingly busy ocean.

The New England Aquarium and the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, both in Boston, received word from Interior Department officials last month stating that the department was terminating funds for research to help protect whale populations, effective immediately. The cut halted a 14-year-old whale survey program that the aquarium staff had been carrying out from small airplanes piloted over a swath of ocean where three wind farms — Vineyard Wind 1, Sunrise Wind, and Revolution Wind — are now being built.

Federal officials did not publicly announce the cancellation of funds. In a statement to Canary Media, a spokesperson for the New England Aquarium confirmed the clawback, saying that a letter from Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management dated Sept. 10 had “terminated the remaining funds on a multi-year $1,497,453 grant, which totaled $489,068.”

The aquarium is currently hosting the annual meeting of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium, a network of scientists that study one of the many large whale species that reside in New England’s waters. News of the cut to the aquarium’s research project has dampened the mood there. And rumors have been circulating among attendees about rollbacks to an even larger research program, a public-private partnership led by BOEM that tracks whales near wind farm sites from New England to Virginia.

Government emails obtained by Canary Media indicate that BOEM is indeed shutting down the Partnership for an Offshore Wind Energy Regional Observation Network (POWERON). Launched last year, the program expanded on a $5.8 million effort made possible by the Inflation Reduction Act, deploying a network of underwater listening devices along the East Coast “to study the potential impacts of offshore wind facility operations on baleen whales,” referring to the large marine mammals that feed on small krill.

POWERON is a $4.7 million collaboration, still in its infancy, in which wind farm developers pay BOEM to manage the long-term acoustic monitoring for whales that’s required under project permits. One completed wind farm, South Fork Wind, and two in-progress projects, Revolution Wind and Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind, currently rely on POWERON to fulfill their whale-protecting obligations.

With POWERON poised to end, wind developers must quickly find third parties to do the work. Otherwise, they risk being out of compliance with multiple U.S. laws, including the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act. Dominion Energy, one of the wind developers participating in POWERON, did not respond to a request for comment.

BOEM officials made no public announcement of POWERON’s cancellation and, according to internal emails, encouraged staffers not to put the news in writing.

“It essentially ended,” said a career employee at the Interior Department who was granted anonymity to speak freely for fear of retribution. The staffer described the government’s multimillion-dollar whale-monitoring partnership as “a body without a pulse.”

The grim news of cuts coincided with the release of some good news. On Tuesday, the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium published a new population estimate for the North Atlantic right whale, an endangered species pushed to the brink of extinction by 18th-century whaling. After dropping to an all-time low of just 358 whales in 2020, the species, scientists believe, has now grown to 384 individuals.

Concern for the whale’s plight has been weaponized in recent years by anti–offshore wind groups, members of Congress, and even President Donald Trump in an effort to undermine the wind farms in federal court as well as in the court of public opinion.

“If you’re into whales … you don’t want windmills,” said Trump, moments after signing an executive order in January that froze federal permitting and new leasing for offshore wind farms.

This view stands in stark contrast with conclusions made by the federal agency tasked with investigating the causes of recent whale groundings.

A statement posted on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s website reads: “At this point, there is no scientific evidence that noise resulting from offshore wind site characterization surveys could potentially cause whale deaths. There are no known links between large whale deaths and ongoing offshore wind activities.”

Climate change has made it difficult for researchers to discern the impacts of wind turbines on whales’ food supply. A government-commissioned report released by the National Academies in 2023 concluded that the impacts of New England’s offshore wind farms on the North Atlantic right whale were hard to distinguish from the effects of a warming world.

For much of the past month, since the aquarium got word of its funding being cut, its researchers have not been able to conduct whale-spotting flights. During this time, construction on Vineyard Wind and Revolution Wind in the southern New England wind energy area plowed forward.

Developers are required to have dedicated observers keeping watch for marine mammals from all construction and survey vessels. But, when it comes to spotting elusive leviathans, nothing quite beats a birds-eye view. The aquarium’s work surveying whales is important for several reasons, according to Erin Meyer-Gutbrod, an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina, who called the clawback “disappointing.”

The project has generated America’s longest-running dataset tracking whale movements near planned and active wind farm areas, she said.

The aquarium’s aerial monitoring dates back to 2011, when the footprints of today’s wind projects were first being sketched out. Historically, North Atlantic right whales were known to feed near southern New England during the winter and spring seasons. In 2022, the aquarium’s dataset allowed researchers to make a remarkable discovery: Unlike in most places on the East Coast, a small number of whales were appearing there year-round. The scientists believe that warmer waters driven by climate change have made the area an “increasingly important habitat” for these whales.

Meyer-Gutbrod said the species’ newly established presence should be a reason for the government to better scrutinize wind farm plans and adapt construction activities.

“Monitoring in and around the lease sites is critical for characterizing right whale distribution. The whales often have seasonal patterns of habitat use, but these patterns are changing. We can’t rely exclusively on historical surveys to guide future offshore development projects,” said Meyer-Gutbrod.

She stressed the importance of continued monitoring to better understand the well-documented hazards to these whales — vessel strikes and rope entanglement from fishing activities — which carry on along the margins of New England’s wind farms. Life-threatening entanglement has been documented in the zone long monitored by aquarium staff. For example, in 2018, aerial researchers were the first to identify that a male right whale, known to scientists as #2310, was caught in fishing rope. A rescue team was unsuccessful at dislodging the rope.

The Interior Department’s cuts come at a time when its own leader is expressing concern for whale populations.

“I’ve got save-the-whale folks saying, ‘Why do you have 192 whale groundings on the beaches of New England?’’” said Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, at an event on Monday hosted by the American Petroleum Institute. He said he was paying attention to people claiming that humpbacks, rights, and other whale species started stranding en masse when “we started building these things,” referring to turbines.

No evidence supports these claims. In fact, Tuesday’s news that the North Atlantic right whale population grew by about 2% from 2023 to 2024 may be the strongest rebuke of Burgum’s statements. That time period coincided with the busiest time for U.S. offshore wind farm construction to date.

Since 2017, the imperiled whale has in fact experienced an annual “unusual mortality event.” Between 10 and 35 whales have shown up dead or seriously injured each year, many displaying injuries consistent with a boat strike. Vineyard Wind 1, America’s first commercial-scale offshore wind farm to get underway, didn’t start at-sea construction until 2022.

Remarkably, there’s been no right whale deaths documented in 2025 — even as five massive wind projects press on with construction in their home range. Heather Pettis, a scientist with the New England Aquarium, attributed this milestone to ongoing “management and conservation efforts,” which include the kind of close monitoring just scuttled by federal cuts.

The aquarium’s spokesperson told Canary Media that its aerial survey team conducted a flight over the southern New England wind energy area on Saturday “using other funding.” It’s unclear how long the program can survive without federal support.

On Monday, an aquarium staffer emailed a group of external scientists, welcoming “any suggestions that you might have for how to continue these surveys.”

Utilities tend not to be big fans of rooftop solar, which eats into their revenues by reducing customer reliance on the power grid. A new Ohio lawsuit spotlights the tension between utilities and customers over the clean-energy technology.

The case deals with a monthly charge imposed by the city of Bowling Green’s municipal utility on its few customers with solar panels on their rooftops. Customers who use batteries to store surplus solar power pay even more.

Residents Leatra Harper and Steven Jansto claim the charge, which for them amounts to roughly $56 per month, is an unlawful “tax or penalty.” When combined with the city’s partial payment for power fed back into the grid, it almost doubles the payback period for their $37,000 solar system, the couple said.

The city argues the fee is needed to make sure other customers don’t subsidize those with rooftop solar. As households that produce some of their own electricity buy less from the utility, they pay less for fixed costs built into its retail rates, such as staffing, grid equipment, and maintenance. The utility would then look to other customers to make up the difference.

The situation echoes “cost-shift” arguments that have dogged rooftop solar around the nation. It could also be a preview of a statewide battle to come as the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio gears up to review and revise its net-metering rules, which determine how solar owners are compensated for the energy they send to the grid. Municipal utilities like Bowling Green are not subject to these rules, but the dynamics around the fairness of rooftop solar rates are similar in either case.

For their part, Harper and Jansto installed rooftop solar panels and battery storage at their home in 2019 and 2020 with hopes of lowering their electric bills and cutting their carbon footprint. The investment will eventually pay for itself because they now buy less electricity from the utility while getting some credit for excess fed back to the grid.

“We could get to near net-zero with a cost up front, but with a payback,” said Harper, who is managing director of the FreshWater Accountability Project, an environmental group.

Residential solar doesn’t just help those who invest in it.

“Rooftop solar helps to provide electricity locally. It reduces overall demand,” said Mryia Williams, Ohio program director for the nonprofit group Solar United Neighbors. That means less wasted energy because the power doesn’t need to travel as far as imported electrons, and it lowers stress on the transmission system as climate change exacerbates extreme weather and energy demand grows.

Energy fed into the grid from homeowners’ renewable energy systems can save other customers money, too.

“The highest demand periods on the grid tend to coincide with times when residential solar power is producing at its peak,” said Tony Dutzik, an associate director and senior policy analyst for the Frontier Group, a sustainability-focused think tank. “Those tend to be the times that utilities spend the most money to provide power for their customers.”

The health and environmental benefits of rooftop solar are “pretty obvious,” especially when excess energy offsets purchases from inefficient gas-fueled peaker plants, Dutzik continued. Less consumption of fossil fuels lowers greenhouse gas emissions and other pollution that is linked to multiple illnesses and more than 8 million deaths per year worldwide — problems that could worsen in the U.S. as the Trump administration rolls back climate policy.

Policymakers have “oftentimes undervalued the benefits that rooftop solar can bring, and when you fail to really account for the benefits, you tend to wind up in the situation where people think it’s not fair,” Dutzik said.

Along those lines, Brian O’Connell, utilities director for Bowling Green, said via email that the city adopted its $4-per-kilowatt monthly charge for installed renewable capacity “to ensure rooftop solar customers were paying for the electric service they were receiving, and that the rooftop solar customers were not being subsidized by non-solar customers.”

The rationale resembles an argument promoted by ALEC, the American Legislative Exchange Council, since 2014. The Center for Media and Democracy has long criticized the group for coddling the fossil-fuel industry while working to suppress the vote and stifle dissent.

Consumer advocates and some academics have made similar cases in California, whose solar capacity leads the nation for both rooftop and overall.

But Harper and Jansto were surprised when they learned Bowling Green adopted its “Rider E” charge roughly six months after work on their home’s renewable energy system wrapped up.

The utility had seemed friendly toward solar: Its website touts the significant share of its power that comes from renewables. Yet while the city aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, it does have a long-term “take-or-pay” contract to get about half of its electricity from the Prairie State coal plant in Illinois.

Legal and constitutional claims in the couple’s Sept. 19 complaint include unlawful and irrational discrimination. The City of Bowling Green filed its answer on Oct. 14, denying liability and asserting governmental immunity and other defenses.

O’Connell said the $4/kW rate for the charge resulted from a cost-of-service analysis by the municipal utility’s consultant, Sawvel & Associates. The city charges a general retail rate of about 13 cents per kilowatt-hour for any electricity it sells to customers. However, it credits rooftop solar owners just 7.5 cents per kilowatt-hour for whatever they supply to the grid.

O’Connell responded to Canary Media’s request for information about how the Rider E rate was calculated by sharing two spreadsheets. Each lists total savings or costs for the utility from a rooftop solar customer’s energy production, including what the utility saves by not paying other sources for capacity, transmission, and wholesale energy when customers feed excess power onto the grid.

But the documents don’t detail how the utility spends the solar surcharge. It’s unclear whether the rooftop solar fees are helping pay for the Prairie State coal plant: O’Connell’s response to Canary Media’s question merely noted the city still has to purchase energy from the electric market.

Harper and Jansto’s case will move through legal motions and pretrial fact-finding, called discovery, during the coming months. Meanwhile, advocates worry about the broader questions the case raises.

“We can look at it both ways with who’s supporting whom whenever rooftop solar is installed,” said Williams of Solar United Neighbors. In her view, “it’s hard to believe that it’s some sort of subsidized rate,” especially if solar customers get only partial credit for letting others use their excess energy.

Ultimately, Dutzik said, rate systems still should not discourage people from investing in renewable energy for their homes. Indeed, if high fees delay recovery of investments for too long, “fewer people are going to get solar,” Dutzik said. “And that is going to drive up costs for other consumers.”

This summer, an ammonia-powered ship completed its maiden voyage in eastern China, becoming the first of its kind to run purely on the carbonless compound. Around the same time, in Denmark, the shipping giant Maersk launched a big container ship that can use methanol, making it the fourteenth and largest vessel yet in the company’s growing low-carbon fleet.

Efforts like these are playing out worldwide as the maritime industry works to replace dirty diesel fuel in oceangoing ships, which haul everything from T-shirts and tropical fruit to solar panels, smartphones, and steel rebar. But the progress to date has been piecemeal, representing only a sliver of the world’s oil-guzzling freighters and tankers.

Up until last week, the United Nations’ International Maritime Organization appeared on the cusp of approving a strategy to supercharge shipping decarbonization worldwide. The plan was set in motion in 2015, after the U.N. adopted the Paris Agreement, clarifying the urgent need for countries and companies to reduce planet-warming pollution to zero.

“It sent a signal for the [maritime] industry to start thinking ahead,” said Narayan Subramanian, an expert on international climate policy and clean energy finance at Columbia Climate School.

In the ensuing decade, the IMO worked to hash out regulations that could jumpstart a universal transition toward cleaner ships. The agency landed on the Net-Zero Framework, which would require ships to use more low-carbon fuels and also establish a tax on carbon emissions — setting the first binding carbon-pricing scheme for an entire industry.

“This is not coming out of left field. It’s not being imposed overnight,” Subramanian said last week before IMO officials put the framework to a vote.

Yet on Oct. 17, after a full-throttle offensive from the Trump administration, the IMO moved to delay making any decision on the landmark decarbonization strategy by one year, keeping the industry locked in limbo. Many fuel producers, shipbuilders, and cargo owners have said they need reassurance that shipping is, in fact, charting a cleaner course before they invest billions of dollars in making new fuels and building related infrastructure.

“There is a lack of incentive globally for shipping operators to use clean fuels,” said Jade Patterson, an analyst for the research firm BloombergNEF. He said the framework would improve the business case for using hydrogen-based fuels like ammonia and methanol, which are significantly more expensive than oil- and gas-based fuels.

A smaller group of IMO members is meeting in London this week to drill down on the finer details of the proposed regulations, which will come up for a vote again in October 2026. But it’s unclear whether any global environmental agreement can succeed while President Donald Trump is in office.

In the meantime, the industry will continue guzzling greater volumes of fossil fuels as shipping activity grows over time.

Tens of thousands of merchant ships ply the oceans every year to haul roughly 11 billion metric tons of goods. Together, they’re responsible for about 3% of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions.

The Net-Zero Framework was meant to give teeth to the nonbinding climate goals that IMO adopted in 2023. Member countries set near-term targets for reducing cargo-ship emissions by at least 20% by 2030, compared to 2008 levels. They also called for curbing emissions by at least 70% by 2040, and for reaching net-zero emissions “by or around” 2050.

Countries further agreed to have 5% to 10% of shipping’s energy use come from zero- or near-zero-emissions fuels and technologies by 2030.

Current adoption of those fuels amounts to a tiny droplet in an ocean’s worth of oil. Much of it is driven by voluntary efforts by companies like Maersk, which face pressure from investors and customers to clean up their fleets. Meanwhile, regional environmental policies are taking effect. European nations and China are working to rein in ship-engine pollution, and they and other countries — including Brazil, India, and, until recently, the United States — are steering government funding into hydrogen production.

Hydrogen is a key component of ammonia and methanol — two common chemicals that can be used in engines or fuel cells. How clean those fuels actually are depends largely on whether the hydrogen is produced using renewables, or the way that most H2 is made today: with fossil fuels. Renewable diesel, another lower-carbon option for powering vessels, also uses hydrogen in its production process.

If every project to produce green ammonia, green methanol, and renewable diesel comes online as planned, and if the fuels only go toward powering ships — not airplanes or vehicles or to other uses — they would make up less than 20% of global shipping’s fuel needs in 2030, which are expected to reach 290 million metric tons that year, Patterson said.

Those are two enormous “ifs.” Many of the announced fuel projects are facing serious headwinds, including high inflation, soaring production costs, and the Trump administration’s steep tariffs and clean-energy funding cuts. IMO’s recent decision to punt on its net-zero vote only deepens those challenges.

Last year, Danish energy giant Ørsted canceled plans to build a green-methanol plant in Sweden, citing weaker-than-expected interest from the maritime sector. Another Ørsted methanol project in Texas is facing uncertainty after the U.S. Department of Energy in May revoked an award of up to $99 million for the facility, as part of sweeping cuts to the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations. In the Netherlands last month, Shell said it is abandoning construction on a biofuels plant in Rotterdam owing to the fuel’s lack of competitiveness.

“What we’ve seen is that this lack of demand and the shift in policy has led many projects to fold,” said Ingrid Irigoyen, president and CEO of the Zero Emission Maritime Buyers Alliance. “But that’s not because they weren’t good projects. These are good fuels that we need, and which are vastly scalable.”

The buyers alliance is a nonprofit group of about 50 multinational companies that helps negotiate clean-fuel contracts — including for waste-based biomethane — between producers, vessel operators, and firms that put their goods on ships. Irigoyen said such voluntary initiatives are meant to be a “catalyst” that helps to scale production and bring down costs of alternative fuels, not the sole engine of shipping decarbonization.

“We can’t do it alone,” she added.

Even as shipping-industry groups and climate experts push for a global policy, there’s still widespread disagreement about how the framework should work in practice. Environmental groups oppose including crop-based biofuels, like soy and palm oil, given that their production can lead to forest loss and increase overall emissions. Policy analysts note that the ripple effects of higher fuel costs and carbon taxes across supply chains could disproportionately affect small and developing economies.

As IMO members navigate those questions, shipbuilders and owners are holding their breath for the answers.

This year, the number of new orders for alternative-fueled vessels has markedly declined compared to last year as companies adopt a “wait and see” approach, according to Jason Stefanatos, global decarbonization director at DNV.

In September, the advisory firm recorded no fresh orders for ships capable of running on methanol or ammonia, though nearly 360 methanol ships and nearly 40 ammonia ships are on the books through 2030.

Subramanian noted that vessels and port equipment are often designed to last for decades, and that many shipping firms are at the point of deciding whether to invest in a status-quo fleet or the next, cleaner generation.

Decarbonization “is a very natural opportunity to upgrade shipping infrastructure that’s otherwise been around for 30 or 40 years,” he said. “And the investment-certainty piece is key to that.”

The Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations was supposed to be a launchpad for ambitious projects to help America lead the way on cleaner power and manufacturing. Now it’s been reduced to a shell of itself.

As the Trump administration slashes spending and fires workers across the federal government, the U.S. Department of Energy has emerged as one of the hardest-hit agencies — and perhaps no other of its divisions has been singled out as deliberately as OCED.

It’s a dramatic reversal for the four-year-old office. During the Biden administration, Congress endowed it with nearly $27 billion to try to scale up cutting-edge technologies that could curb planet-warming pollution from industrial facilities and power plants. Trump officials have in recent months hollowed out the office, canceling billions in previously issued awards for everything from low-carbon chemical manufacturing to rural energy resiliency, while also dismissing over three-quarters of its employees.

The situation is best summarized by the budget the White House has requested for OCED for the next fiscal year: $0.

Experts and insiders warn that the tumult within OCED and the DOE more broadly is eroding the private sector’s trust in the federal government and its ability to drive energy innovation.

“The administration has really created a chilling effect on the willingness of future early-stage technology developers to work with the Department of Energy,” said Advait Arun, a senior associate for energy finance at the Center for Public Enterprise, a nonprofit think tank.

Ultimately, that will stifle investment not only in the clean energy sectors the Trump administration dislikes but in those it has championed as well, such as advanced nuclear and geothermal. Former OCED staffers and contractors, who were granted anonymity to speak freely, told Canary Media that the disruption is a major setback for America’s efforts to launch the world’s next generation of energy technologies and industries.

“We are eliminating ourselves as a leader in the clean energy space, especially for the industrial complex,” one person said. “What I’m seeing is China is about to slip right into that position. Just logically and economically, I don’t understand the steps that are being taken.”

Congress created OCED in December 2021 to help deploy first-of-a-kind projects at commercial scale. The idea was for the government to absorb some of the risks and provide early capital to usher companies across the valley of death that lurks between promising research pilots and real-world operations that can move the needle on decarbonization.

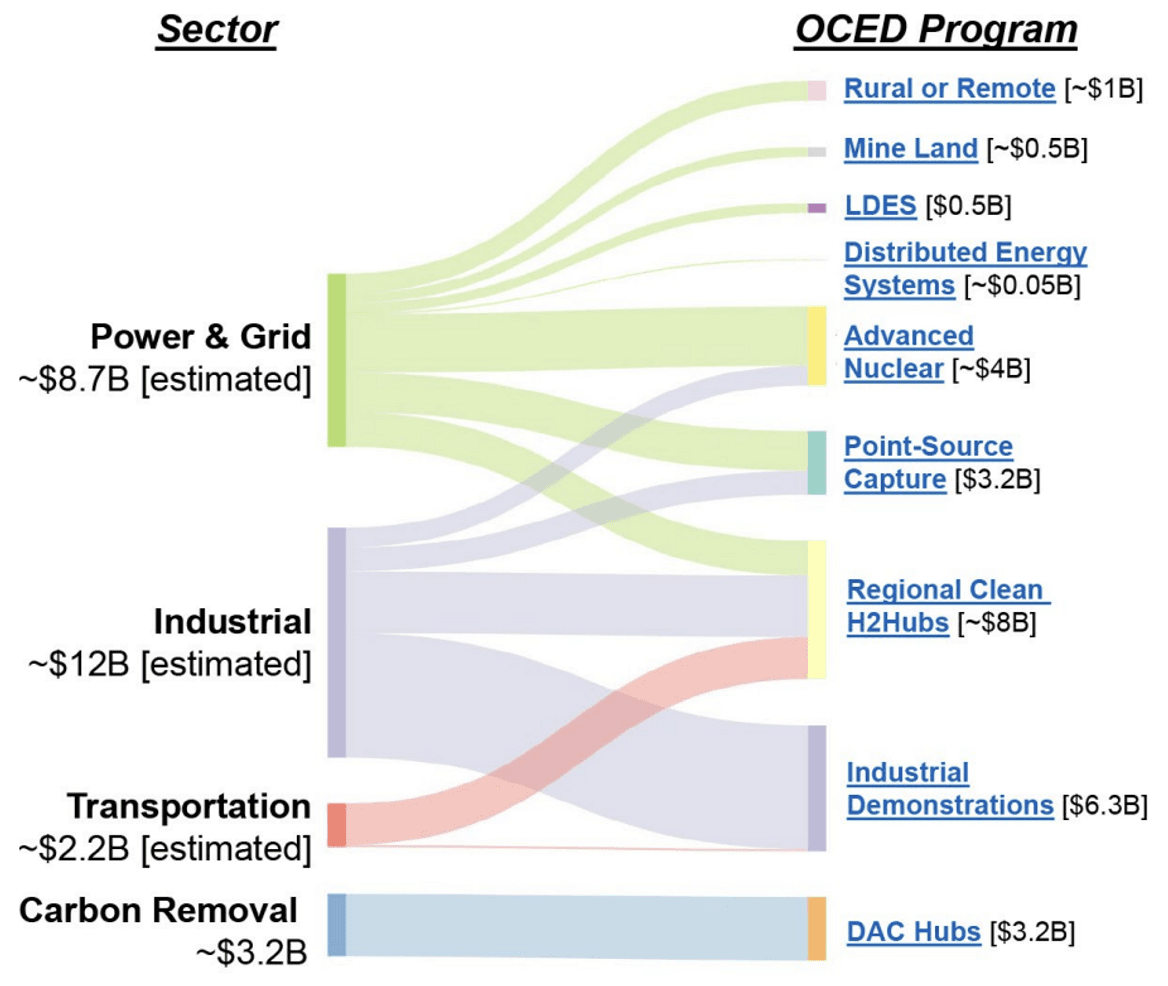

The 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law provided OCED with about $21 billion over five years to scale up emerging technologies like small modular reactors and long-duration energy storage, and to advance ambitious “hubs” for producing hydrogen fuel and capturing carbon dioxide from the sky and smokestacks. In 2022, Congress gave OCED an additional $5.8 billion through the Inflation Reduction Act to help decarbonize U.S. manufacturing of materials like steel, cement, and chemicals.

“A lot of this stuff is a chicken-and-egg situation, where the private sector doesn’t want to come in [and invest] yet because it’s not proven,” said Zahava Urecki, a senior policy analyst with the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Energy Program.

“But we need the technology to go through this [demonstration] process in order to make sure it becomes proven, so that eventually we can have this in society,” she added. “And that’s where the federal government plays a key role.”

Over the course of three years, the office selected 116 projects in 42 states to receive over $25 billion in federal funding. For most awards, participating companies were required to cover at least 50% of total costs themselves — meaning the office expected its portfolio to spur nearly $65 billion in private investment, in addition to creating potentially hundreds of thousands of jobs.

Among the biggest winners were seven regional hydrogen hubs and two major direct-air-capture initiatives that would remove CO2 directly from the sky. The choices were not always broadly celebrated, and critics raised concerns that the hydrogen and carbon-capture initiatives in particular would do more harm than good for the climate by propping up unproven, energy-intensive projects involving fossil-fuel companies.

But other OCED picks garnered more public applause — and supported industries that President Donald Trump had flagged as priorities. In 2024, the office selected Cleveland-Cliffs for an award of up to $500 million to begin lower-carbon steel production in Middletown, Ohio, the hometown of Vice President JD Vance. Another manufacturer, Century Aluminum, got up to $500 million to help it build the nation’s first new aluminum smelter in decades, which would be powered by carbon-free electricity.

Former OCED staffers said they attempted to brief the incoming Trump administration on the office’s portfolio and to explain how they could support the president’s stated goals of boosting “American energy dominance” and “advancing innovation.”

However, from the time Trump took office on Jan. 20, “It became pretty clear that it didn’t really matter,” a former employee said.

It was quickly evident that Trump would, in fact, be adopting the right-wing policy platform Project 2025 after trying to distance himself from it on the campaign trail. The blueprint — which outlines ways to erase federal spending — called for eliminating “all DOE energy demonstration projects, including those in OCED,” in order to avoid “distorting the market and undermining energy reliability.”

For one staffer, “it all started crumbling” on Day 1, when the White House issued an executive order to halt federal work on “diversity, equity, and inclusion” — a measure that affected OCED’s grant recipients. Under former President Joe Biden, the office required participants to create community-benefit plans to ensure the billions in taxpayer dollars went to projects that included neighbors in the planning process and supported local economies. Under Trump, the strategy became a liability.

A blitz of federal funding freezes and layoffs — and court reversals and injunctions — then ensued, creating chaos across federal agencies and for all the outside companies that hold or held government contracts. In late January, the White House extended federal workers a “deferred resignation offer” that would allow people to resign from their jobs and go on leave with pay through Sept. 30, the end of the fiscal year.

Few OCED staffers initially took the offer. But after several months of chaos, about 77% of workers at OCED signed the deal when the White House extended it again in April. Insiders say that figure is likely even higher now. Across the DOE, some 3,200 employees within the agency’s roughly 17,000-person workforce opted to leave.

“That’s when folks at OCED actually started to realize it was going to be personnel changes that would first impact the projects, and not the program cuts,” according to a former employee.

On May 15, about a month after the staff exodus, Energy Secretary Chris Wright said the DOE would begin scrutinizing federal grants to “identify waste of taxpayer dollars.”

The agency started requesting additional information for 179 awards totaling over $15 billion, with a focus on large-scale commercial projects. Wright claimed that these awards were “rushed out the door, particularly in the final days of the Biden administration,” and required further review to ensure that individual projects were “financially sound and economically viable.”

Less than 3% of the over $25 billion in OCED’s awards portfolio had actually been paid to projects as of March 31, in part because larger grants were meant to be doled out in tranches over a long development timeline, according to EFI Foundation, a nonpartisan organization led by Ernest Moniz, who served as energy secretary during the Obama administration.

Project developers interviewed by EFI claimed that, contrary to Wright’s statement, OCED’s “due diligence was more rigorous than what private-sector investors would conduct” and that, rather than undergo the office’s laborious process, “faster decisions would have better aligned with developer timelines,” the foundation said in a June report.

Wright didn’t wait long to begin nixing projects. In late May, he announced the termination of 24 awards issued by OCED totaling over $3.7 billion, including funding for carbon capture and sequestration and projects within the office’s Industrial Demonstrations Program that aimed to reduce emissions from iron, cement, glass, and chemicals production.

“These clean energy projects were enshrined into law by bipartisan majorities and represent the will of Congress,” Sen. Martin Heinrich, Democrat from New Mexico, said in a recent statement to Canary Media. Heinrich and other congressional Democrats sent a letter to Wright on Sept. 9 accusing the DOE of undertaking a “haphazard, disorganized, and politically driven” cancellation process.

More funding cuts arrived earlier this month, when the DOE said it was slashing 321 grants for projects almost entirely in states that voted for Democratic nominee Kamala Harris in the 2024 presidential election. A spreadsheet of the cuts lists 11 newly affected OCED projects totaling nearly $2.5 billion, including for two major hydrogen projects planned in the Pacific Northwest and California. The October list also repeats five OCED-backed initiatives that first appeared in the May announcement.

Project developers have said they’re appealing the award terminations and are in continued talks with the DOE. Still, it’s unclear how much capacity the office has anymore to helm those discussions.

Wright said in an Oct. 3 interview that more cancellations would follow, and early last week rumors swirled about a second spreadsheet that appeared to outline deeper cuts for carbon-removal projects, hydrogen hubs, and other OCED projects. The nature of the list remains unclear, but if it proves to be a signal of cuts to come, it would cancel another $6.1 billion in awards from OCED.

The project areas that have yet to be cut — or to appear on any potential hit lists — include advanced nuclear energy and critical minerals. Additionally, the energy agency said it has started tapping OCED’s authority to make some new grants for Trump’s favorite energy source: coal-fired power plants. Should the office shutter, these awards would likely be managed by other divisions within the DOE.

Alex Kizer, a senior policy advisor at EFI, noted that gutting OCED won’t end America’s efforts to decarbonize heavy industries.

In the case of cement and steel, demand for low-carbon materials is growing within U.S. and global markets as tech giants look to build less carbon-intensive data centers, and as state governments and European and Chinese regulators work to rein in industrial pollution. Still, losing grants — and the DOE’s seal of approval — will undoubtedly make it harder and more expensive for companies to raise private capital for commercial-scale projects. Stifling the DOE’s role as a gatherer and publisher of real-world lessons could further slow progress, Kizer said.

“The potential for breakthrough across different energy sectors is so significant,” he said of OCED’s work, noting that “a relatively small investment from taxpayers could have an enormous benefit to taxpayers over time,” in terms of delivering cleaner, more reliable energy. “Who says no to that?”