DALLAS — The automated machinery and bright, clean factory floor wouldn’t look out of place in the solar manufacturing hub of Changzhou, China. But every so often, the pristine industrial order was punctuated by, of all things, carrier robots blasting psychedelic rock as they rolled down the aisles.

T1 Energy runs this half-mile-long factory just 15 miles south of Dallas, where seven parallel manufacturing lines produced more than 20,000 photovoltaic modules on the day I visited in October. After ramping up in the early months of 2025, T1 is on track to produce up to 3 gigawatts this year, but with the systems dialed in and workers operating 24/7, the facility has been running fast enough to make 5 gigawatts in a year, said Russell Gold, executive vice president for strategic communications.

The factory is finding its legs just as the Trump administration vaporizes pro–clean energy policies and instead pursues a fossil-heavy vision of “energy dominance.”

“What the manufacturers here really want, and really need, is just certainty,” said MJ Shiao, vice president of supply chain and manufacturing at the trade group American Clean Power. What they got this year was “policy whiplash,” he said, which has caused the Biden-era drumbeat of clean-energy manufacturing announcements to morph into a chorus of cancellations, per data from Atlas Public Policy.

But T1 nonetheless is staking a claim to homegrown American solar energy and making the case that it’s still lucrative. The firm has plowed ahead this year, signing deals for U.S.-made polysilicon and U.S.-made steel frames and preparing to build its own solar-cell fabrication facility.

Gold pointed to the booming demand for solar, which has become the biggest source of new power plant capacity getting built in the U.S. today by a long shot.

“We absolutely believe that it is a great time to be making solar,” said Gold, who came to T1 in May after a career covering energy for The Wall Street Journal. “The main reason is we’re in the middle of this massive trend toward more electricity usage … Solar is the scalable energy resource that can produce the amount of electricity that is demanded today.”

T1’s facility bustles with robots and people working side by side.

Autonomous units ferry materials around and handle the heavy lifting of pallets stacked high with finished panels. Specialized machines cut cells and string them together with electrically conductive filaments, while others sandwich rows of cells between glass, snap their frames into place, and roll them through a high-temperature curing process.

Today those frames are made out of imported aluminum, but next year T1 will replace them with U.S.-made steel frames from Nextpower, the solar equipment juggernaut formerly known as Nextracker. Dan Shugar, Nextpower’s CEO, had visited T1 shortly before I did; given Shugar’s well-known love for classic guitar rock, technicians reprogrammed the autonomous guided vehicles’ warning sounds with grooves by Santana and AC/DC. (“Because of course, AC/DC — it’s appropriate,” Gold told me.) The sounds stuck around.

The factory was running two 12-hour shifts every day, with workers watching over the robots and stepping in when necessary to correct their work. Signs listed every key notice in English, Mandarin, and Spanish, and the 1,200-person workforce reflected the diversity of the Texas metropolis.

The only production line that wasn’t operating during my visit had been geared toward smaller residential panels. T1 had paused production in response to slack demand, Gold said, and was working to adjust the line to produce panels for the booming utility-scale market instead.

Around the factory, a few clues hinted at a more nuanced backstory than the triumphal, homegrown American solar narrative that T1 leads with. Much of the production machinery sported the logo of Trina Solar, a Chinese company that ranks among the most prolific solar manufacturers in the world. At the end of the tour, we surveyed the warehouse area, where pallets of finished modules awaited shipping in Trina Solar–branded cardboard boxes.

The Chinese company, in fact, built the factory, as part of a wave of foreign investment in U.S. solar panel assembly that kicked off back in 2018, when the first Trump administration levied new tariffs on Chinese imports. Chinese investment in U.S. solar factories accelerated considerably when the Biden administration passed industrial policy that rewarded manufacturers for U.S. production and developers for installing domestically made equipment.

Within two and a half years of Biden signing the Inflation Reduction Act, the U.S. built enough factories to assemble all the panels it needed. The entire supply chain had not been re-shored, but it was well on its way — a remarkable turnaround for a sector long since decimated by cheaper Chinese competition. The lone exception to that collapse was First Solar, which makes a thin-film cadmium-telluride panel, in contrast to the dominant silicon-based photovoltaics; that company, too, has expanded its U.S. footprint, recently completing a factory in Louisiana and announcing a new one in South Carolina.

Even before Trump won his second election, though, bipartisan political sentiment was shifting against Chinese companies’ benefiting from federal incentives, even those that built state-of-the-art factories in the U.S. and staffed them with American workers.

Trina had constructed the Dallas factory and had just begun the laborious process of commissioning the lines when it evidently saw the writing on the wall. Trina sold the factory in December to Freyr Battery, which had tried and failed to build battery gigafactories in Norway and Georgia. The entity officially rebranded as T1 Energy in February and now is headquartered in the U.S. and traded on the New York Stock Exchange.

Gold demurred on the question of who approached whom with an offer. In any case, after the transaction, T1 owned the factory, which it calls G1 Dallas, and Trina retained a 13.2% stake in the company. That arrangement neatly anticipated the “foreign entity of concern” (FEOC) rules that Trump signed into law this summer: Republicans restricted clean energy tax credits from going to companies with too much ownership by Chinese companies.

“FEOC is going to be a challenge for this industry because China has dominated the solar industry for years,” Gold said. But the December transaction took the factory from a level of Chinese ownership that would violate the subsequent FEOC rules to a level “well below the equity cutoff,” Gold noted. “We were doing it before Congress spelled out what people need to do.”

Congress set the FEOC restrictions to kick in at the start of 2026, which means some domestic solar factories will, ironically, cease to qualify for the made-in-America tax credits under their current ownership structures. Santa’s sack just might hold some factories for corporations, like T1, that have made it onto the FEOC “nice list.”

As for the ongoing use of Trina-branded containers for shipping T1 modules, “there was no reason to make extra waste by trashing a bunch of boxes,” Gold said.

Solar panels are the last step of the supply chain, and the one with the lowest barrier to entry: Though highly specialized and automated, the machines at T1, as at Qcells’ facility in Dalton, Georgia, are assembling components produced elsewhere. Making silicon cells requires a step change in capital and technical proficiency, as do the precursor steps of producing wafers and polysilicon ingots.

The U.S. has proved it can make solar panels that, if not economically competitive with those made in China, can get by in a protectionist trade regime that, at least for now, is still buoyed by federal incentives. Cell production is ticking up in the U.S., which currently has factories that can use them — Suniva and ES Foundry each brought about 1 gigawatt of cell capacity on line in the past year. Qcells is finishing up a 3.3-gigawatt cell-production facility in Georgia.

This constitutes an “orderly strategic buildout” for the domestic industry, said Shiao of American Clean Power. “The cell producers aren’t going to come until the module producers come … Right now, we’re starting to see that larger growth of cell production because we’ve had those years for those investment decisions to come to fruition.”

T1 is also getting in on the photovoltaic-cell action. By the end of the year, Gold said, the company expects to break ground on a $400 million cell-fabrication plant, or fab, in Rockdale, Texas, down the road from another silicon-oriented business: a major Samsung chip-fab development. The plan is to ramp up to 2.1 gigawatts of cell production by the end of 2026 and add another 3.2 gigawatts in a subsequent phase.

That’s one angle. This fall T1 also bought a minority equity stake in a fellow upstart solar manufacturer called Talon PV, which is building a 4.8-gigawatt cell fab in Baytown, Texas, and targeting production in early 2027.

Until those factories open, T1 is importing cells from non-FEOC countries, Gold said.

A T1 deal with legacy glass producer Corning signals a further deepening of the U.S. solar supply chain. Corning announced in October that it had opened polysilicon ingot and wafer production in Michigan — the crucial precursor to cell production, and something the U.S. hasn’t had in almost a decade. Business launched on an auspicious note, as Corning has already sold 80% of all its expected production for the next five years to customers including T1.

With that industrial breakthrough, the pieces have fallen into place for a fully American supply of the key silicon solar-panel components. Now the question is whether this fledgling supply chain can survive the tumultuous policy swings of the second Trump presidency.

Over the past decade or so, the Connecticut Green Bank, the first green bank in the United States, has taken on an unusual role — that of a “public developer” of solar projects for schools, cities, and low-income housing across the state.

“There are all sorts of public institutions that take in public money and give a loan, a grant, and that’s all they do,” said Jason Kowalski, executive director of the Public Renewables Project. “This is completely different in what it can achieve.”

The Connecticut Green Bank’s Solar Marketplace Assistance Program Plus (Solar MAP+) actively engages in originating, developing, and even owning projects, he said. To date, the program has deployed $145 million in capital on nearly 54 megawatts’ worth of solar projects that are expected to help save a collective $57 million in energy costs, according to bank data shared with Canary Media.

Though the approach is unusual for a public entity, it needn’t be, Kowalski said. In fact, it is a model that cash-strapped state governments should consider closely as federal clean-energy tax credits disappear and energy costs rise. That’s particularly true for the 16 states, plus the District of Columbia, that have created a government-backed or nonprofit green bank since Connecticut first launched its version in 2011.

The bank’s program targets sectors that private lenders and solar developers might shy away from because of perceived credit risks or low returns on investment, Kowalski explained. It taps into low-cost financing available to state entities and builds portfolios of projects to achieve economies of scale.

Then the revenues generated from those projects are “recycled”: used to expand the pool of capital from which it can make loans for other projects that help achieve Connecticut’s clean energy and environmental justice goals.

While some private-sector solar industry players may see the Solar MAP+ approach as infringing on their turf, state-backed agencies “see it as expanding the role of the private-sector installation business,” Kowalski said.

That’s certainly the case for the school solar projects that Solar MAP+ has built, said Tish Tablan, senior program director at Generation180, a clean energy advocacy group.

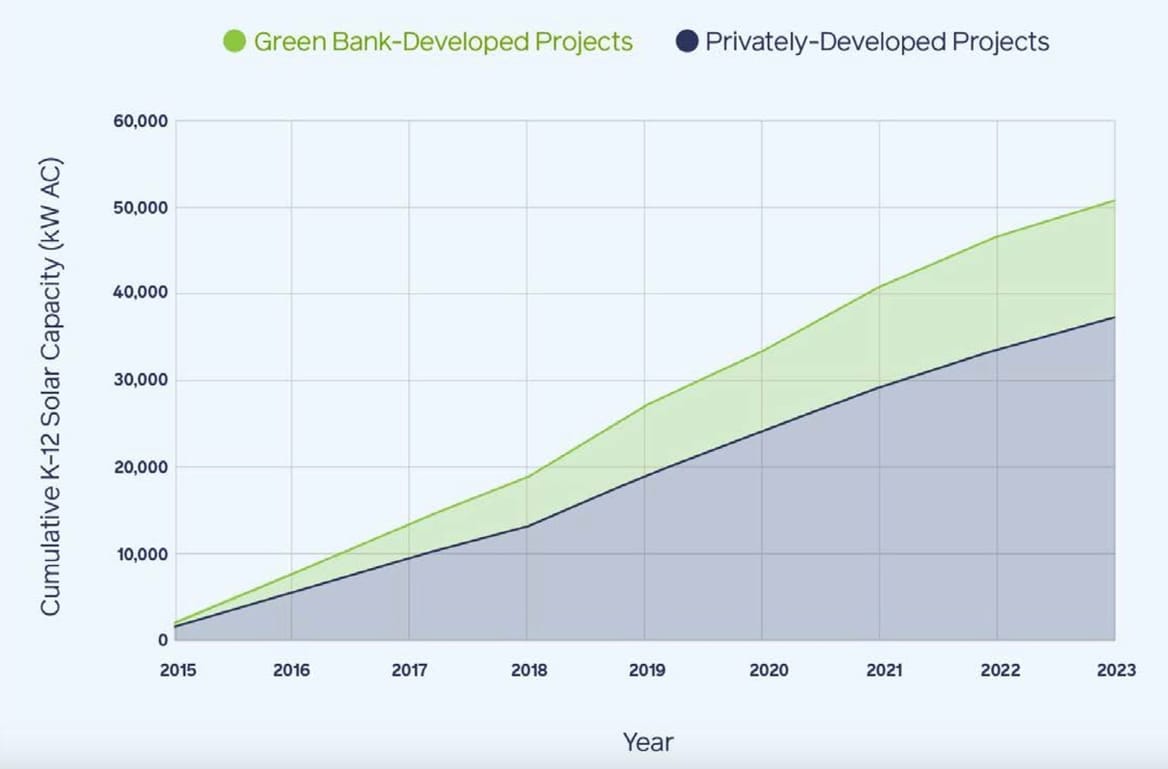

A September report by Tablan’s and Kowalski’s groups and the Climate Reality Project found that Connecticut — the third-smallest state by land mass and 29th in population — ranks fifth in the country for total solar capacity installed on K–12 schools and second (behind Hawaii) in the percentage of K–12 schools with solar.

The Connecticut Green Bank developed 27% of school solar installations in the state from 2015 to 2023, according to the report. Those installations are projected to save schools tens of millions of dollars in energy costs, and more than half are in low-income and disadvantaged communities.

The same model can help schools and public buildings do more than solar, Tablan added. “We can look at electrification, we can look at heat pumps, we can look at solar-plus-storage, we can look at microgrids.”

This kind of financial support is increasingly important as the Trump administration cancels federal funding for clean energy projects more broadly, and in disadvantaged communities in particular, Tablan and Kowalski said. That includes the administration’s move to claw back $20 billion in federal “green bank” funds meant to promote precisely this kind of public-sector finance, which is now being challenged in court.

Solar MAP+ evolved largely as a response to gaps in the state’s broader solar market, said Mackey Dykes, the Connecticut Green Bank’s executive vice president of financing programs.

The same 2011 law that launched the bank also created state solar incentives meant to boost development across multiple sectors of the economy, Dykes said. “But there were some areas where we didn’t see a lot of activity. We sat down and started to figure out why that was.”

The first targets were state agencies that were lagging in solar development, despite their access to relatively low-cost capital, he said. This indicated that incentives alone weren’t the solution. It turned out that those agencies “needed help with documentation structures, with procurement, with project labor agreements,” he said. “We put that together, and projects started happening.”

“Then we realized we built this Swiss Army knife of tools that we could bring to bear in other sectors where there were gaps in solar deployment,” Dykes said. The Connecticut Green Bank also started looking at municipalities that were lagging in using solar incentives, particularly smaller towns, he said. At around the same time, he noted, “we realized the solar incentive program in the state was undersubscribed for school projects,” and they set out to fix that.

Bundling multiple school projects can help lower costs. Dykes cited the example of a 67-kilowatt system at an intermediate school in Portland, Connecticut. “You’d have trouble attracting attention for a project that small,” he said. “When you combine it with dozens of projects, and have developers competing with a pool of projects, the projects become more feasible,” with the Connecticut Green Bank serving as a clearinghouse for hiring installers and securing financing at a larger scale.

Tablan highlighted the similarities with Generation180’s work with schools. “If you ask any public-sector entity, they’re going to say budget and cost are the first concerns,” she said. Most of the country’s school solar projects have been developed via third-party ownership models, and “Connecticut Green Bank has taken that approach” as well, she said.

The wraparound services that Solar MAP+ offers bring more than money to the equation, said Advait Arun, senior associate for capital markets at the Center for Public Enterprise. The nonprofit think tank uses the term “public development” to characterize the way public entities can expand beyond financing to include “all of the steps in a project development pipeline,” including ownership, operations, and maintenance.

That’s not a normal role for green banks, Arun said. As of the end of 2023, green banks and partners had driven a cumulative $25.4 billion in public and private investments, according to the Coalition for Green Capital, a group that includes green banks and environmental advocacy organizations. Most of that funding has focused on de-risking harder-to-finance sectors, such as energy efficiency and rooftop solar installations in low-income neighborhoods, without taking the plunge into the full range of project development activities that Solar MAP+ is involved in.

But even under this model, there are gaps that private sector financiers don’t want to fill. That’s where public-sector ownership can help, as the data on school solar’s growth in Connecticut indicates, Arun noted.

“We’re not used to this kind of thing in this country,” he said. But “without the Connecticut Green Bank de-risking schools for this kind of solar investment, the market would have remained smaller than it could be.”

That direct involvement has helped smaller school districts build more ambitious project pipelines over time, said Emily Basham, director of financing programs for Solar MAP+.

In Manchester, Connecticut, once the private developers caught wind of state involvement, city leaders “were somewhat bombarded with proposals,” Basham said. “They wanted to do their first projects with us, to cut their teeth on it.”

The more than $100,000 in projected annual energy savings from the solar systems at seven municipal buildings, including six schools, helped the city gain confidence in moving forward with a subsequent project that has converted one of its elementary schools into the state’s first net-zero school by adding advanced insulation systems and on-site geothermal energy, she said.

The Connecticut Green Bank’s dive into parts of the project development process has drawn fire from solar industry groups in the state.

In 2024, solar developers pushed lawmakers to restrict the bank from developing projects at schools and municipal sites, citing concerns around a lack of competitive bidding. That effort was defeated after representatives of state and local government as well as labor and clean-energy advocates at the Connecticut Roundtable on Climate and Jobs weighed in to support the bank.

Some of those supporters came from Branford, Connecticut, which contracted with the Connecticut Green Bank to build solar arrays on two elementary schools.

“We’re a municipality with limited staff and dedicated volunteers, but you can’t ask volunteers to procure and oversee a project of that size,” said Jamie Cosgrove, who recently ended a 12-year stint as Branford’s first selectman — the equivalent of the town’s mayor — to join the Connecticut Green Bank’s board of directors. “We use them as a trusted source, and we feel comfortable engaging with them to move forward on a number of these projects.”

The two elementary schools’ solar installations are expected to save about $248,000 over the next 20 years, Cosgrove noted — not a huge payback for a private-sector developer. “Maybe these projects aren’t significantly cash-flow positive. But there are other priorities we have as a municipality. We’re looking to advance our clean energy goals.”

Branford has also done plenty of work with the private sector, including a 4.3-megawatt solar array on a former gravel yard and solar projects at the town’s high school and fire station, said Jim Finch, Branford’s finance director. “It’s not an either-or thing,” he said.

“I don’t think it’s unreasonable for a state entity that’s identified reducing carbon emissions as a public purpose to do this kind of work,” Finch added. “We have organizations to deal with clean air, financing sewer projects, et cetera — we can have public purpose entities do that.”

State development finance agencies — government entities in all 50 states that support economic development through a variety of financing structures — could also take on this kind of public developer model, he said.

New York could be a first target, said Kowalski of the Public Renewables Project. The New York Power Authority, the public agency that owns and develops transmission and generation in the state, has been tasked with building gigawatts of large-scale renewables. Backers of more muscular government intervention to rejuvenate the state’s faltering progress on clean energy are calling for the NYPA to follow Connecticut’s lead in building solar on school rooftops.

Finding ways to push more finance into solar projects has become a more pressing matter, Kowalski said, both to offset the loss of solar tax credits from the megalaw passed by Republicans in Congress this summer and to combat fast-rising electricity costs across the country.

“Our whole report is an answer to how to respond to the tax credits getting rolled back. If there’s a shortfall, we think we have an answer,” Kowalski said. “Public developer models can be part of an affordability agenda on climate.”

The world is clamoring for more electrons. It’s getting them from solar and wind.

Between January and September, the two clean-energy sources grew fast enough to more than offset all new demand worldwide, according to data from energy research firm Ember.

Power demand rose by 603 terawatt-hours compared to that same time period last year. Solar met nearly all that new demand on its own, increasing by 498 TWh. Wind generation, meanwhile, climbed by 137 TWh.

What happens when clean energy not only meets but exceeds new power demand? We start to burn less fossil fuels. At least a little less: Through Q3, fossil-fuel generation dropped by 17 TWh, compared to the first three quarters of 2024. This trend is expected to continue through the end of the year. Ember forecasts that fossil-fuel generation will have experienced no notable growth in 2025 — something that hasn’t happened since the height of the Covid-19 pandemic.

It’s unclear whether this flatlining marks the beginning of the end for fossil-fueled electricity or whether it’s just a pause before another surge in dirty power. The answer will more or less be determined by what grows faster: electricity demand or renewable energy.

Common consensus is that the world’s appetite for electricity will expand rapidly in the coming years. The planet is warming and driving increased use of air conditioning. AI developers are building massive power-hungry data centers. Cars, homes, and factories are being electrified. That all adds up: The International Energy Agency expects power demand to rise by a staggering 40% over the next decade.

Meanwhile, it’s almost not worth considering long-term forecasts about the growth of clean energy, given how inaccurate they’ve been in the past. Analysts have consistently underestimated solar, in particular.

For the global power sector to truly decarbonize, carbon-free energy needs to not only keep pace with electricity demand but far outrun it. Let’s hope solar continues to overperform.

Restrictions on solar and wind farms are proliferating around the country, with scores of local governments going as far as to forbid large-scale clean-energy developments.

Now, residents of an Ohio county are pushing back on one such ban on renewables — a move that could be a model for other places where clean energy faces severe restrictions.

Ohio has become a hot spot for anti-clean-energy rules. As of this fall, more than three dozen counties in the state have outlawed utility-scale solar in at least one of their townships.

In Richland County, the ban came this summer, when county commissioners voted to bar economically significant solar and wind projects in 11 of the county’s 18 townships. Almost immediately, residents formed a group called the Richland County Citizens for Property Rights and Job Development to try and reverse the stricture.

By September, they’d notched a crucial first victory, collecting enough signatures to put the issue on the ballot. Next May, when Ohioans head to the polls to vote in primary races, residents of Richland County will weigh in on a referendum that could ultimately reverse the ban. It’s the first time a county’s renewable-energy ban will be on the ballot in Ohio.

From the very beginning, “it was just a whirlwind,” said Christina O’Millian, a leader of the Richland County group. Like most others, she didn’t know a ban was under consideration until shortly before July 17, when the commission voted on it.

“We felt as constituents that we just hadn’t been heard,” O’Millian said. She views renewable energy as a way to attract more economic development to the county while reining in planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions.

Brian McPeek, another of the group’s leaders and a manager for the local chapter of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, sees solar projects as huge job opportunities for the union’s members. “They provide a ton of work, a ton of man-hours.”

Many petition signers “didn’t want the commissioners to make that decision for them,” said Morgan Carroll, a county resident who helped gather signatures. “And there was a lot of respect for farmers having their own property rights” to decide whether to lease their land.

While the Ohio Power Siting Board retains general authority over where electricity generation is built, a 2021 state law known as Senate Bill 52 lets counties ban solar and wind farms in all or part of their territories. Meanwhile, Ohio law prevents local governments from blocking fossil-fuel or nuclear projects.

The Richland County community group is using a process under SB 52 to challenge the renewable-energy ban via referendum. Under that law, the organization had just 30 days from the commissioners’ vote to collect signatures in support of the ballot measure.

All told, more than 4,300 people signed the petition, though after the county Board of Elections rejected hundreds of signatures as invalid, the final count ended up at 3,380 — just 60 more than the required threshold of 8% of the number of votes in the last governor’s election.

Although the Richland County ban came as a surprise to many, it was months in the making.

In late January, Sharon Township’s zoning committee asked the county to forbid large wind and solar projects there. After discussion at their Feb. 6 meeting, the county commissioners wrote to all 18 townships in Richland to see if their trustees also wanted a ban. A draft fill-in-the-blanks resolution accompanied the letter.

Signed resolutions came back from 11 townships. The commissioners then took up the issue again on July 17.

Roughly two dozen residents came to the July meeting, and a majority of those who spoke on the proposal were against it. Commissioners deferred to the township trustees.

“The township trustees who were in favor of the prohibition strongly believe that they were representing the wishes of their residents, who are farming communities, who are not fans of seeing potential farmland being taken up for large wind and solar,” Commissioner Tony Vero told Canary Media.

He pointed out that the ban doesn’t cover the seven remaining townships and all municipal areas. “I just thought it was a pretty good compromise,” he said.

The concerns over putting solar panels or wind turbines on potential farmland echo land-use arguments that have long dogged rural clean-energy developments — and which have been elevated into federal policy by the Trump administration this year. Groups linked to the fossil-fuel industry have pushed these arguments in Ohio and beyond.

“It’s a false narrative that they care about prime farmland,” said Bella Bogin, director of programs for Ohio Citizen Action, which helped the Richland County group collect signatures to petition for the referendum. Income from leasing some land for renewable energy can help farmers keep property in their families, and plenty of acreage currently goes to growing crops for fuel — not food. “We can’t eat ethanol corn,” she added.

Under Ohio’s SB 52, counties — not townships — have the authority to issue blanket prohibitions over large solar and wind farms, with limited exceptions for projects already in the grid manager’s queue.

In Richland County’s case, the commissioners decided to defer to townships even though they didn’t have to.

The choice shows how SB 52 has led to “an inconsistently applied, informal framework that has created confusion about the roles of counties, townships, and the Ohio Power Siting Board,” said Chris Tavenor, general counsel for the Ohio Environmental Council. Under the law, “county commissioners should be carefully considering all the factors at play,” rather than deferring to townships.

Even without a restriction in place, SB 52 lets counties nix new solar or wind farms on a case-by-case basis before they’re considered by the Ohio Power Siting Board. And when projects do go to the state regulator, counties and townships appoint two ad hoc decision-makers who vote on cases with the rest of the board.

As electricity prices continue to rise across Ohio, Tavenor hopes the state’s General Assembly will reconsider SB 52, which he and other advocates say is unfairly restrictive toward solar and wind — two of the cheapest and quickest energy sources to deploy.

“Lawmakers should be looking to repeal it and make a system that actually responds to the problems facing our electric grid right now,” he said.

Commissioner Vero, for his part, said he has mixed feelings about the referendum.

“It’s America, and if there’s enough signatures to get on the ballot, more power to people,” he said. However, he objects to the fact that SB 52 allows voters countywide to sign the petition, even if they don’t live in one of the townships with a ban, and said he hopes the legislature will amend the law to prevent that from happening elsewhere.

Yet referendum supporters say the ban matters for the entire county.

“It affects everybody, whether you live in a city, a township, or a village,” McPeek said. As he sees it, restrictions will deter investment from not only companies that build wind and solar but also those that want to be able to access renewable energy. “To me, it just is bad for the county — the whole county, not just one or two townships.”

Renewable-energy projects also provide substantial amounts of tax revenue or similar PILOT payments for counties, helping fund schools and other local needs. “I think it’s important for my children to have more clean electric [energy] and all the opportunities that go along with having wind and solar,” Carroll said.

Now that the referendum is on the ballot, the Richland County group will work to build more support and get out the vote next spring. “Education and outreach in the community is basically what we’re going to focus on for the campaign coming up in the next few months,” O’Millian said.

“So now it goes to a countywide vote, and the population of the county gets to make that decision, instead of three guys,” McPeek said.

Brookfield Renewable Partners has signed yet another deal to power a tech giant’s data centers with one of its existing hydroelectric plants, heralding a potential lifeline for America’s aging dams.

In its quarterly earnings call with investors this month, Brookfield said it had signed a 20-year contract with Microsoft “at one of our hydro facilities” in the nation’s largest grid system, PJM Interconnection.

The deal is part of a broader agreement, announced last year, to supply Microsoft’s data centers with 10.5 gigawatts of renewable electricity. But it’s the first contract under that framework to support a specific hydroelectric facility. Brookfield declined to disclose which of its dams is part of the deal. Near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the company operates at least two stations with a combined capacity of nearly 700 megawatts in PJM’s 13-state territory. On the earnings call, Brookfield suggested it may acquire a third plant in the grid system.

The move comes nearly four months after Brookfield signed the biggest deal for hydropower in history: a $3 billion agreement to supply Google’s data centers with up to 3 gigawatts of power for the next two decades.

It also comes at a make-or-break moment for the U.S. hydropower sector, which is one of the few forms of always-on, carbon-free energy available in a country clamoring for clean electrons. Most projects are decades old and will have to undergo relicensing processes over the coming years.

Both of Brookfield’s hydroelectric facilities in Pennsylvania — the 252-megawatt Holtwood Hydroelectric Project, first opened in 1910, and the nearly 418-megawatt Safe Harbor Hydroelectric Project, built in the early 1930s — are up for relicensing in the next five years.

As part of the Google and Microsoft deals, Brookfield said it was able to “upfinance” both facilities, a term that typically describes when private equity companies refinance an existing loan and borrow more money on top of the remaining balance. That could be an indicator that the data center deals are helping Brookfield fund the upgrades and other requirements needed to obtain new operating licenses.

“We continue to evaluate the opportunity to acquire hydro [plants] which would fit well within our portfolio,” Connor Teskey, president of Brookfield Asset Management, said on the earnings call.

Nearly 450 hydroelectric stations totaling more than 16 gigawatts of power-producing capacity are slated for relicensing across the U.S. in over the next decade. That’s roughly 40% of the nonfederal fleet (the government owns about half the country’s hydropower facilities).

The relicensing process for hydropower is uniquely onerous, involving multiple federal, state, and local regulators. Some power plant owners and advocates have accused regulators of using the process to try to squeeze the facilities for additional benefits, such as paying for roads or infrastructure unrelated to a dam itself, which owners say they can’t afford. Faced with relicensing, some stations have simply shuttered, their owners deciding it’s easier to surrender their permits than to make costly upgrades and regional investments needed to win support.

“This is major infrastructure. These facilities cost billions of dollars,” Malcolm Woolf, the National Hydropower Association’s chief executive, previously told Canary Media. “They’re like bridges and roads. They get a license for 50 years. The state agencies view [the relicensing process] as an opportunity to extract concessions from what they view as a deep pocket.”

In the 1970s, he added, “maybe the industry was a deep pocket.”

“But now,” Woolf said, “with the low cost of other fuels like wind and solar and gas, it’s driving these facilities to bankruptcy and to surrender licenses.”

The ocean has beckoned to legions of energy entrepreneurs before dashing their hopes against the rocks. Now a new company is heeding the siren call — but with a twist.

Italy’s Sizable Energy launched in 2022 to build pumped hydro energy storage under the ocean. Cofounder and CEO Manuele Aufiero pursues that outlandish vision with the methodical diligence he picked up as a seasoned nuclear engineer. Now, the firm has deep-water wave testing under its belt, and in October it closed $8 million in seed funding to build its first offshore demonstration project.

This venture takes aim at two longstanding, elusive cleantech dreams: reinventing pumped hydro and harnessing the sea for clean energy. It’s an ambitious project that must navigate choppy seas, literally and figuratively, to succeed. But if Sizable can pull it off, it would unlock low-cost, long-duration storage that could accelerate the broader shift to clean energy.

Even as lithium-ion batteries surge in popularity, legacy pumped-hydro projects still store more gigawatt-hours than any other technology. The latter harnesses gravity, using excess electricity to pump water uphill and releasing it to turn turbines when more energy is needed. This simple, century-old technology rarely gets built anymore, however; besides the environmental implications of forming enormous reservoirs, today’s fast-moving energy markets aren’t particularly encouraging for power plants that take many years to build and cost billions of dollars up front.

That’s not to say pumped hydro never gets built, Aufiero told me — Switzerland recently completed a facility in a high mountain valley, but it took 14 years. Part of the problem there is that every mountain is different, he explained: the height, flow rate, and energy equipment must be customized for each location.

But the ocean, he said, offers the chance to standardize this otherwise bespoke tech — making it far easier and quicker to deploy.

“We are unfolding the possibility of building the system even before knowing exactly where you are going to deploy,” he said. “We do that by deploying offshore. Water is the same everywhere.”

Specifically, Sizable has designed a gravity-based storage system that shuttles a briny liquid up and down a vertical pipe affixed to the seafloor. Inflatable membranes form reservoirs at the bottom and on the surface; from above, it looks like a giant floating donut. The system connects to the land-based grid, and uses power to pump the brine up through the plastic pipe. Reversing that regenerates power.

Startups have tried reinventing pumped hydro by running train cars filled with rocks uphill, loading up ski-lift-style cable systems with weights, and stacking enormous blocks with robotic cranes. Each of those began with the same claims about mechanical simplicity and ended up in the junkyard of cleantech ideas. But where those ventures started on the ground and had to build up, Sizable Energy starts on the ocean surface and goes down.

“There’s a lot of ocean depth in the world — it’s not oversubscribed,” said Bruce Leak, general partner at Playground Global, which led the seed round.

The relatively low costs of Sizable’s design could make it competitive for long-duration storage, something experts think the grid needs but nobody has really delivered yet.

Lithium-ion batteries are increasingly competitive for shorter durations, like four hours. But they get prohibitively expensive for much longer than that. To deliver the same megawatt capacity over 12 or 24 hours (through the night or a whole day of cloudy weather) requires stacking a bunch more batteries, and that stacks the cost.

Any company that wants to compete in long-duration storage has to find materials and designs that make it dirt cheap to add hours of capacity. Traditional pumped hydro does this by filling a large reservoir with water. Sizable chose a double-walled membrane to fill with brine, which fits the cheap and scalable bill. Adding more vertical feet of plastic pipe is pretty inexpensive, too.

The power equipment costs less than 700 euros ($810) per kilowatt in the long term, competitive with pumped hydro, Aufiero said. Where the technology really shines is in the marginal cost of adding more storage duration: less than 20 euros ($23) per kilowatt-hour, at scale. That’s right on par with what Form Energy is targeting with its iron-air battery, an attempt at a mass-produced electrochemical battery for 100 hours of duration.

Sizable is shooting for eight hours to 24 and beyond. The economics improve at a larger scale: If you’ve got to install a mooring system and connect a marine cable to the grid, you might as well ship more power through it rather than less.

That’ll take some time to work up to. Sizable already built a kilowatt-scale proof of concept, which it floated at the Natural Ocean Engineering Laboratory in Reggio Calabria, Italy. In September, the company subjected its design to a bombardment of artificial waves in the gigantic pool at the Maritime Research Institute Netherlands, which vets the durability of marine engineering. The successful performance in those tests set the stage for the recent fundraising round.

With the cash infusion, the team is building a 1-megawatt device, which will sport a 50-meter (164-foot) radius and occupy up to 500 meters (1,640 feet) of ocean column off the coast of Reggio Calabria.

Sizable is funding this project itself, since it can’t yet show financiers the real-world performance data they need to underwrite investment. It will be fully functional, using scaled-down components because of its diminutive size, but it won’t connect to the grid. Sizable has already secured a 10-megawatt grid connection in southern Italy for its first truly commercial development.

The unenviable challenge facing Aufiero is to fortify his invention against the torments of the sea, without spending so much money armoring it that it loses its low cost.

“Doing something in the ocean, it is a challenge, but it’s also an opportunity for massive scalability,” Aufiero said. He set out to design a “simple system that can be scaled without too many surprises.”

Wave action has literally sunk many hopeful ocean-energy pilot projects. But such devices in the past sought to harness the renewable power of the waves through direct contact. Sizable Energy only needs the ocean as a uniform space to operate in, so its technology tries to minimize wave contact as much as possible.

Two outer rings of plastic pipe were engineered to disrupt waves before they hit the floating reservoir. In the event that strong surf or heavy rain threatens to weigh down the reservoir, bilge pumps activate to clear out the liquid.

In Europe, people have been leasing seabed for energy projects at grand scale for decades. Sizable will apply to the same regulatory bodies that oversee offshore wind, but needs a much smaller footprint per megawatt.

In fact, offshore wind farms are an attractive potential site for the startup’s contraption, Aufiero said. By colocating, Sizable could share the export cables, and firm up the booms and busts of wind generation by storing it locally and distributing it to the grid as needed. Leak, the investor, likened this pairing to transforming an offshore wind plant into a nuclear power plant by converting variable generation into predictable, baseload clean energy.

For their part, the lead investors at Playground Global find the challenge of surviving Neptune’s wrath exhilarating.

“As engineers, we love things that are hard,” Leak told me. “If it’s a good idea that anybody can do, what’s your difference?”

Australia’s power sector is steadily shifting away from coal and toward running on 100% renewable energy. Now the country is trying to ensure some of its biggest electricity users — aluminum smelters — aren’t left behind in the clean-energy transition.

The Australian government is developing a Green Aluminium Production Credit, or GAPC, to reduce the cost of using solar, wind, and energy storage to power the country’s four giant smelters. The AU$2 billion (US$1.3 billion) program is part of a larger federal industrial policy that aims to decarbonize Australia’s economy over the next decade.

“Australia is sending a signal that it wants this industry to stay,” said Marghanita Johnson, CEO of the Australian Aluminium Council. “Therefore, what do we need to do to keep the industry during this challenging transition?”

Smelters everywhere are power-hungry facilities. That’s because the process of converting raw materials into aluminum can require hundreds of megawatts of electricity running at near-constant rates. In Australia, a country of nearly 28 million people, the four smelters consume roughly 10% of the nation’s electricity and contribute about 4% of total greenhouse gas emissions.

As in many places, renewables are the country’s cheapest new electricity sources, and battery storage costs are plunging. But the fact that wind and solar power aren’t available around the clock means that smelters need to procure more total megawatts from multiple sources to make sure that, at any moment, they have enough capacity to operate, Johnson said.

Australia’s Department of Industry, Science and Resources is still finalizing the design of its GAPC. Generally, though, it will cover between 30% to 40% of the extra costs associated with using renewables to produce aluminum instead of conventional sources like coal and gas. The program will provide credits to aluminum producers for every metric ton of “green” aluminum they produce for up to 10 years, starting from the 2028-2029 financial year.

The initiative is part of an emerging movement by countries to subsidize or otherwise support domestic heavy industries as they work to decarbonize, said Chris Bataille, an adjunct research fellow at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

He noted that, under the Biden administration, the United States had been considering developing tax credits to incentivize industrial manufacturers to use more renewable energy, though those discussions have sputtered under the second Trump administration. In China, meanwhile, the central government is investing more money into projects that reduce or replace coal use in sectors like steel, cement, and chemicals.

”This is going to be a big question going forward: How [can countries] get these big industries off of fossil fuels and onto using variable renewable power, and all the adaptations that are necessary?” Bataille said.

Aluminum smelters typically sign long-term contracts with utilities that lock in the price of electricity the companies pay over years or decades. In Australia, those contracts are coming to an end, and as manufacturers look to sign new deals, they’re finding themselves in a dramatically different energy market, Johnson said.

Today, three of Australia’s smelters get most of their electricity from coal-fired power plants: Rio Tinto’s Boyne Island facility in Queensland, Alcoa’s Portland plant in Victoria, and Tomago Aluminium’s smelter in New South Wales. Only Rio Tinto’s Bell Bay smelter in Tasmania runs predominantly on hydropower.

Coal power is steadily declining in Australia as renewables surge, owing primarily to market forces. About 90% of the aging coal fleet will likely be gone by 2035, and the rest could shutter later that decade, the head of the Australian Energy Market Operator, which oversees the nation’s power markets, recently told Canary Media’s Julian Spector. (Australia banned nuclear energy decades ago, so it’s not an option.)

For now, coal still accounts for 46% of Australia’s annual electricity production, according to the International Energy Agency. Renewables contribute about 35%, though existing projects aren’t necessarily located near smelters that need them.

Rio Tinto, which owns a majority share of Tomago Aluminium, warned in late October that the smelter is bracing for a potential shutdown by the end of 2028 owing to the soaring costs of both “coal-fired and renewable energy options from January 2029” that would make the facility’s operations commercially unviable. Tomago is the country’s largest smelter, accounting for about 40% of Australia’s annual aluminum production.

“There is significant uncertainty about when renewable projects will be available at the scale we need,” Jérôme Dozol, CEO of Tomago Aluminium, said in an Oct. 28 statement.

Johnson said Tomago’s troubles point to the broader limitations of initiatives like the GAPC. While the production credit can reduce power costs for smelters, other measures are needed to support the buildout of not just wind, solar, and battery storage but also transmission lines and grid infrastructure that connect the resources to the energy-gobbling smelters.

The Australian Aluminium Council is also advocating for energy policies that reward smelters for the benefits they are able to provide to the grid. For example, smelters can rapidly reduce their power consumption for about an hour at a time to help stabilize the system during emergencies. Alcoa is participating in such a demand-response program in Australia, as is Rio Tinto’s Tiwai Point smelter in New Zealand. Aluminum plants can also be an important source of demand for solar power plants in particular, since factories use plenty of power during the day when households generally consume less.

“We’re doing a lot of work here in Australia, in terms of the energy transition and how all these pieces of the puzzle need to fit together,” Johnson said.

U.S. Rep. Mikie Sherrill won the governor’s race in New Jersey on Tuesday running on a platform of keeping electricity prices down. Environmental groups see Sherrill’s election as a triumph for the Garden State’s struggling offshore wind sector.

Sherrill, a four-term Democrat and a U.S. Navy veteran, arrived on the political scene in 2017 and advocated for offshore wind projects on Capitol Hill. As a gubernatorial candidate, she was one of only three Democrats who explicitly endorsed offshore wind on campaign websites early in the race.

Her Republican opponent, Jack Ciattarelli, ran on a promise to ban future offshore wind development. His campaign website sells “stop offshore wind” tote bags, t-shirts, stickers, and beverage koozies. Sherrill handily beat Ciattarelli, winning 56% to 43% at press time.

“In-state produced power through offshore wind and other renewable technologies is the only path forward to ensure carbon reduction while prioritizing price stability, economic growth, and resource adequacy,” said Paulina O’Connor, executive director of the New Jersey Offshore Wind Alliance, an advocacy group whose work is funded in part by wind developers.

Sherrill will take office next year without any offshore wind projects operational or under construction along the state’s roughly 130 miles of coastline. That’s in stark contrast to the other East Coast states that, like New Jersey, have incentivized offshore wind development through tax breaks and have planned grid and clean-energy goals around the sector’s growth. Massachusetts, Virginia, New York, and Rhode Island all have installations completed or currently underway.

New Jersey’s incumbent Phil Murphy, also a Democrat, was once a fierce proponent of offshore wind but has ostensibly distanced himself from the sector in recent months as President Donald Trump’s war on offshore wind proved, in some ways, insurmountable for a lame-duck governor.

The Trump administration has frozen the permitting pipeline for all of New Jersey’s earlier-stage offshore projects. Atlantic Shores, the state’s only fully approved wind farm, had one of its federal permits revoked in March by the Environmental Protection Agency. Shell, the project’s codeveloper, officially withdrew from the project last week.

As governor, Sherrill’s ability to counter federal anti-wind policies will be limited. But she can make sure the state remains a player in the industry, which is still advancing in nearby New York. In that state, one project, South Fork Wind, is fully operational, and another, Empire Wind, is under construction.

Sherrill, for example, could expand funding for programs that train workers for wind jobs. She could increase legal pressure against the Trump administration for obstructing certain projects, as Rhode Island and Connecticut have done. New Jersey’s Attorney General Matthew Platkin, along with 17 other attorneys general, is already suing the Trump administration over its broad-reaching executive order that froze federal permitting for wind power.

Her campaign promise to freeze New Jerseyans’ utility rates through a State of Emergency declaration on Day 1 and to push back on federal overreach signifies a willingness to come out fighting.

“Governor-elect Sherrill campaigned on the need for bold action to reduce family energy costs. [The American Clean Power Association] welcomes the Governor-elect’s recognition that clean power is key to meeting demand and keeping costs low,” said Jason Grumet, CEO of the trade group, in a statement released shortly after Sherrill’s acceptance speech on Tuesday night.

In January, Sherrill will take the reins from Murphy, who set New Jersey on a path to building a 100% zero-emissions power grid by 2035 but ultimately failed to generate any new offshore wind power. New Jersey voted on Tuesday for a candidate who aims to keep the state’s climate ambitions alive. The long-held vision of offshore wind turbines being central to these goals endures — for now.

Two years ago, the Biden administration announced $7 billion in funding for a nationwide network of hydrogen hubs meant to kickstart production of the alternative fuel.

Now, the Trump administration has cast doubt over the future of the program — including the Appalachian Regional Clean Hydrogen Hub, or ARCH2, which features projects in Ohio.

Despite the turbulence, industry leaders said they see a bright future for hydrogen in Ohio.

“We’re building businesses in this state regardless of that federal funding,” said Bill Whittenberger, executive director of the Ohio Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Coalition, at the group’s 2025 symposium, held Oct. 27 and 28 at the Honda Heritage Center in Marysville, Ohio. In his view, federal funding “makes things go a little faster, [but] there’s a strong business case for all the things we’re doing here.”

Many see hydrogen as necessary for decarbonizing hard-to-electrify operations, such as steel and glassmaking, as well as some transportation sectors.

Today, however, few industries use the fuel at a meaningful scale — and very little low-carbon hydrogen is available.

The Biden administration’s hub initiative meant to change that by bringing down the cost of low-carbon hydrogen, which can be produced with renewable energy, nuclear power, or natural gas with carbon capture and storage.

The initiative sparked detailed planning for dozens of projects throughout the hub regions. In Ohio, proposals took on different shapes: One developer wanted to use solar power to make hydrogen for buses in Stark County, while another planned to derive the fuel from a chemical plant’s waste stream. Still others looked to expand storage and refueling operations in central and northeastern Ohio.

The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act also created a lucrative federal tax credit for clean-hydrogen projects, an incentive that successful lobbying preserved through the end of 2027 in Republicans’ massive budget bill signed into law in July. But even with this federal support in place, the nascent industry has been on shaky ground. Some high-profile green-hydrogen projects were already floundering before this year.

The Trump administration’s October cancellation of federal dollars for two of the hubs that focused on hydrogen from renewable energy raised urgent questions about the viability of many hydrogen ventures nationwide.

The fate of the other five hubs remains uncertain. Last month, their names appeared on a leaked Energy Department list alongside a note to “terminate,” but the DOE has not confirmed their status.

Still, conference attendees emphasized, some hydrogen projects are moving forward in Ohio.

There’s the plan from American Electric Power’s Ohio utility to power data centers with fuel cells, for example. It’s part of a broader AEP partnership with Bloom Energy to acquire up to 1 gigawatt of fuel cells to help the giant computing facilities get online faster.

“Speed to power trumps all other things,” said Amy Koscielak, a senior business development leader for AEP.

At the outset, though, the systems planned in central Ohio for Amazon Data Services and Cologix Johnstown will run on natural gas. Eventually, AEP has said, they could switch to run on hydrogen.

Earlier this year, the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio green-lit plans for AEP’s Ohio utility to provide the systems’ output exclusively to those customers, although appeals are pending.

Hydrogen also features in vehicle offerings from American Honda Motor Co. Although its hybrid cars that can use either hydrogen or battery electric power are built in Marysville, most of them go to California.

In general, battery-powered electric vehicles are probably the best option for “small mobility,” said Gary Robinson, vice president of sustainability and business development for the company. Indeed, hydrogen cars remain niche at best. But “trucks, buses, industrial equipment — all of those things, in our opinion, are perfect candidates for hydrogen,” Robinson said. The company is exploring shipping and aviation as other potential markets for fuel cells.

Ohio also has a few projects looking to harness electrolysis — a process that uses electricity to separate water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. If the electricity that feeds into electrolysis is clean, the resulting hydrogen is clean too.

Dayton-based Millennium Reign Energy supplied electrolyzer equipment to provide initial fill-ups for the fuel-cell hybrids that Honda has made in Marysville since last year, and it has provided fueling equipment to other locations in the United States and abroad. The company plans to add two fueling stations for its Emerald H2 network in the Dayton area by April, CEO Chris McWhinney told Canary Media.

Plug Power also relies on electrolyzers to produce its hydrogen. The 28-year-old company’s first big order back in 2007 was for fuel cells to power pallet trucks at a Walmart distribution center in Washington Court House, Ohio, said Mike Ahearn, vice president for North American service. He did not talk about projects the company would do as part of ARCH2, if it moves ahead, but he did describe work outside of Ohio.

Plug Power remains on track to start construction next year on a wind-powered hydrogen plant capable of producing around 45 tons per day in Graham, Texas. “We are on a good trajectory,” Ahearn said, adding that the company’s goal is to turn a profit next year — something it hasn’t done yet over its almost three decades in operation.

Independence Hydrogen, another ARCH2 project-development partner, concentrates on local hydrogen production and distribution. While federal funding remains uncertain, the company still hopes it can move ahead with the Ohio project that would be part of the hub.

The company’s method of making the alternative fuel doesn’t fit neatly on the “hydrogen rainbow” that indicates whether production relies on renewable energy or fossil fuels.

Rather, the source would be an industrial waste stream from the INEOS KOH plant in Ashtabula, Ohio. The plant makes potassium hydroxide and other chemicals, and releases a waste stream that is almost all hydrogen. Independence Hydrogen would basically “clean up” the gas by removing water and other impurities and then compress it for transport.

But “I need an offtaker,” said William Lehner, chief strategy officer for the company. “We would love to provide that project.”

Indeed, most companies at last week’s symposium would love more customers, but it’s unclear how quickly interest in the alternative fuel will ramp up if federal funding for ARCH2 and other hydrogen hubs remains in limbo and if tax incentives aren’t extended further.

The DOE’s “hydrogen shot,” launched in 2021, aimed to scale up the production of clean hydrogen and cut its cost to $1 per kilogram — an 80% reduction — by 2031. While developers would still cover at least half the project costs at the hubs, federal grants would have reduced total expenses and let them charge customers less for their hydrogen. The hope was that the lower prices would stoke demand.

The Trump administration’s actions to dismantle decarbonization policy also raise questions about clean hydrogen’s future. Without sticks that punish greenhouse gas emissions or carrots that make zero- and low-carbon fuels cheaper, a lot of projects face a difficult road ahead.

A longstanding federal tax credit for rooftop solar is about to expire, making it more expensive for homeowners to access cheap, clean energy — and sowing uncertainty for the companies that put photovoltaic panels up on roofs.

But a small Durham, North Carolina, company called EnerWealth Solutions sees a path forward — at least for the next two years. Its model is to buy rooftop solar panels with a tax credit still available to commercial entities and rent them to homeowners, passing along the savings.

It’s an approach that firms around the country can adopt as the beleaguered rooftop solar sector tries to weather the Trump administration’s assault on clean energy.

The leasing strategy could be particularly useful in places like North Carolina, where a robust solar industry has taken root but state policy support for home rooftop panels is waning. In early 2023, funding dried up for a popular rooftop solar rebate program run by Duke Energy, the state’s predominant electric utility. Later that year, Duke began lowering bill credits for customers who send their solar power back to the grid.

A sunny state of 11 million people, North Carolina is a leader on utility-scale solar but middling when it comes to residential solar adoption. Just over 55,000 homes are now equipped with rooftop panels, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, so the industry has ample room to grow.

“It’s so imperative that we’re opening every avenue to get these technologies into the hands of as many North Carolinians as possible,” said Matt Abele, executive director of the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, an advocacy group.

EnerWealth’s first residential leasing customer is one of the industry’s own. A certified public accountant and financial consultant for solar firms, Casey Gilley said installing an array on his Chapel Hill home is something of an unspoken requirement. “You can’t work in the business and not have solar,” he said. “Right?”

While his profession may not be entirely typical, Gilley is an average Tar Heel in other ways. He’s trying to do his part to reduce pollution and save energy. He wants to guard against coming electricity-rate increases. And forking over a down payment on a full-price solar array for his family of five was a no-go.

Plenty of people EnerWealth aims to serve fit that profile, says Brian Liechti, director of solar leasing. That’s why, until the end of 2027, when companies like his can no longer access the tax credit, the goal is simple: “Make hay and electrons while the sun shines,” he said.

Veterans of the solar industry say they’re used to the ebb and flow of policies designed to encourage homeowners to go solar. But there’s no doubt that they’ve had an especially hard year.

Most crushing was the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act by President Donald Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress in July. The law eliminates the 30% tax credit for home solar at the end of this year, nearly a decade sooner than it was previously set to expire. The change is pushing sales to new heights, but a crash is expected once the incentive is gone in 2026.

The White House also clawed back $7 billion in grants intended to help low-income households go solar, including a $156 million initiative projected to benefit 12,000 families across North Carolina. The state’s Attorney General Jeff Jackson is among 23 attorneys general around the country suing the Trump administration for terminating the program, calling the move illegal.

The policy whiplash comes amid a difficult macroeconomic environment for rooftop solar. High interest rates and inflation have lingered for years, dampening interest in the sector among those without the cash to buy a solar array outright.

Despite these woes, North Carolina installers see a few bright spots.

For one, a Duke trial program called PowerPair, in which customers receive a rebate of up to $9,000 for investing in a battery along with a solar array, has seen thousands of enrollees since its launch in the spring of last year. The pilot has reached its limit in the company’s eastern and far western territory but still has room in the central part of the state.

What’s more, a 2017 state law creates a small crack in Duke’s monopoly. While agreements between homeowners and non-utilities for the purchase of electricity are forbidden as ever, the statute allows individuals to rent the use of solar equipment up to a certain cap. This provision has been little-used to date in the residential sector but is a cornerstone of the EnerWealth model.

Then, there’s a final puzzle piece for the company: the pro-solar policy that escaped the purge in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. While incentives for individuals dry up Dec. 31, commercial entities can receive at least a 30% credit for investing in renewable energy through the end of 2027.

EnerWealth, then, can keep buying rooftop solar panels for another two-plus years, benefit from the credit, and then pass on some of the savings to its lessees. For now, the company doesn’t have to fear hitting the Duke solar leasing cap established in 2017. And customers who can cash in on the PowerPair battery incentive while it still lasts will see even more savings.

These federal and state incentives can come together to produce savings for North Carolinians, even in a tough time for rooftop solar.

Though Gilley might conceivably have borrowed money and installed his panels in time to use the expiring tax credit, he chose the EnerWealth lease model instead.

“I ran the numbers of ownership versus lease, and they were very similar,” he said. But what ultimately tipped the scales toward the latter was that it didn’t require a down payment or any ongoing costs. “I didn’t have to come up with any cash,” he said. “Also, I don’t have to worry about any maintenance or any problems for the next 25 years.”

PowerPair is still available in Gilley’s area, so he used the $9,000 rebate as a down payment on the battery and the solar system. He receives net-metering bill credits and still pays Duke for electricity — but about $210 less per month than before. Even with his $150 monthly payment to EnerWealth, Gilley is saving about $60 a month.

His rental payment for the equipment will step up 1.5% each year. “But electricity prices are going to escalate at a much higher pace than that,” he predicted. “So, my annual savings will only grow.”

When the residential tax credit expires in two months, homeowners who want to go solar will have an even easier choice to make: Finance their equipment over time at roughly 7% interest rates or rent it for about 25% less per year, thanks to passthrough savings from the tax credits.

“A lease is the only way to monetize the tax credit for residential systems,” EnerWealth’s Liechti said.

According to EnerWealth calculations, the lower lease payments on a $35,000 battery and solar array mean customers will save nearly $15,000 in overall electricity costs over 20 years. Even those who can pay for a system outright might choose a rental option, which spreads the costs out over time and produces monthly bill savings right away.

Meanwhile, in terms of customer experience, there’s little difference between renting and owning the panels and battery. Homeowners have a buyout option beginning in year seven. If they move, they can purchase the equipment and include the expense in the home’s sale price, or transfer the lease — and monthly bill savings — to the new owners.

While EnerWealth is breaking ground in the solar leasing market in North Carolina, other companies are sure to follow, said Scott Alexander, chief strategy officer for the company.

“We’re just one tool in the toolbox,” he said.

The EnerWealth model does have its limits. It’s only available in Duke territory, which covers most but not all of the state. It’s also much more attractive with the PowerPair rebate, which is soon to dry up and faces an uncertain future after that.

Most of all, the leasing economics will get a lot less appealing in two years, when the 30% tax credit runs out for commercial entities, too.

After that, Alexander said, “we have to innovate. We have to pivot. No business lasts forever. We’ve got two years.”

A correction was made on Nov. 6, 2025: An earlier version of this story mischaracterized the advantages of leasing rooftop solar and a battery versus purchasing a system at full price up front. The latter offers consumers more savings over the long term, according to EnerWealth’s calculations, while leasing provides the advantage of immediate net savings.