As 2023 came to a close, scientists had hoped that a stretch of record heat that emerged across the planet might finally begin to subside this year. It seemed likely that temporary conditions, including an El Niño climate pattern that has always been known to boost average global temperatures, would give way to let Earth cool down.

That didn’t happen.

Instead, global temperatures remain at near-record levels. After 2023 ended up the warmest year in human history by far, 2024 is almost certain to be even warmer. Now, some scientists say this could indicate that fundamental changes are happening to the global climate that are raising temperatures faster than anticipated.

“This shifts the odds towards probably more warming in the pipeline,” said Helge Goessling, a climate physicist at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany.

One or two years of such heat, however extraordinary, doesn’t alone mean that the warming trajectory is hastening. Scientists are exploring a number of theories for why the heat has been so persistent.

The biggest factor, they agree, is that the world’s oceans remain extraordinarily warm, far beyond what is usual — warmth that drives the temperature on land up, as well. This could prove to be a temporary phenomenon, just an unlucky two years, and could reverse.

“Temperatures could start plummeting in the next few months and we’d say it was just internal variability. I don’t think we can rule that out yet,” said Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at Berkeley Earth. But he added, “I think signs are certainly pointing toward fairly persistent warmth.”

But some scientists are worried the oceans have become so warm that they won’t cool down as much as they historically have, perhaps contributing to a feedback loop that will accelerate climate change.

“The global ocean is warming relentlessly year after year and is the best single indicator that the planet is warming,” said Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished scholar with the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Other factors are temporary, even if they leave the world a bit hotter. One important one, scientists say, is that years of efforts to clean up air pollutants are having an unintended consequence — removing a layer in the atmosphere that was reflecting some of the sun’s heat back into space.

Whatever the mix of factors or how long they last, scientists say the lack of clear explanation lowers their confidence that climate change will follow the established pattern that models have predicted.

“We can’t rule out eventually much bigger changes,” Hausfather said. “The more we research climate change, the more we learn that uncertainty isn’t our friend.”

Experts had been counting on the end of El Niño to help reverse the trend. The routine global climate pattern, driven by a pool of warmer-than-normal waters across the Pacific, peaked last winter. Usually about five months after El Niño peaks, global average temperatures start to cool down.

Often, that’s because El Niño is quickly replaced with La Niña. Under this pattern, the same strip of Pacific waters become colder than normal, creating a larger cooling effect on the planet. But La Niña hasn’t materialized as scientists predicted it would, either.

That leaves the world waiting for relief as it confronts what is forecast to be its first year above a long-feared threshold of planetary warming: average global temperatures 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer than they were two centuries ago, before humans started burning vast amounts of fossil fuels. (Formally crossing this threshold requires at least several years above it.)

The year 2023 is the current warmest year on record at 1.48 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial average. However, 2024 is expected to be at least 1.55 degrees, breaking the record set the year before. Last year’s record was further above the expected track of global warming than scientists had ever seen, by a margin of more than three tenths of a degree. This year, that margin is expected to be even larger.

While changes in temperatures of a degree or less may seem small, they can have large effects, Trenberth said.

Like “the straw that breaks the camel’s back,” he said.

That includes increasing heat and humidity extremes that are life-threatening, changing ocean heat patterns that could alter critical fisheries, and melting glaciers whose freshwater resources are key to energy generation. And scientists say if the temperature benchmarks are passed for multiple years at time, storms, floods and droughts will increase in intensity, too, with a host of domino effects.

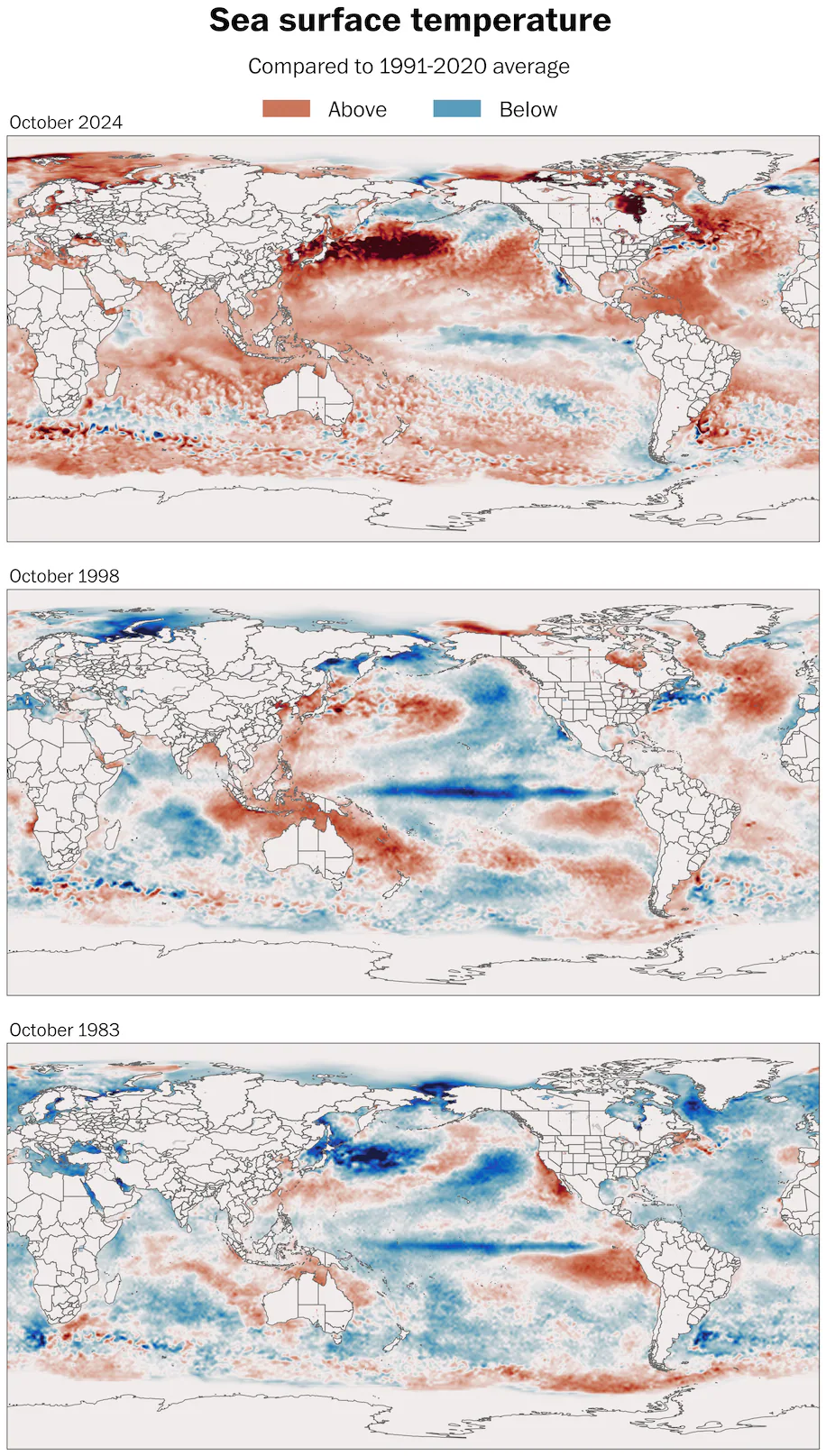

Compared with past years when El Niño has faded, the current conditions are unlike any seen before.

A look at sea surface temperatures following three major El Niño years — 2024, 1998 and 1983 — reveal that a La Niña-like pattern was evident in all three years, with a patch of cooler-than-average conditions emerging in the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

But in 2024, the patch was narrow, unimpressive and dwarfed by warmer-than-average seas that cover most of the planet, including parts of every ocean basin.

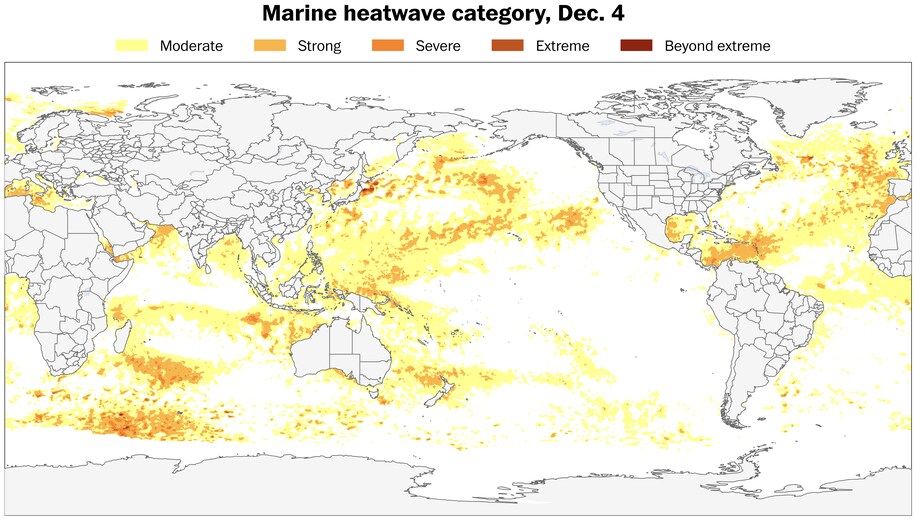

Known as marine heat waves, these expansive blobs of unusual oceanic heat are typically defined as seas being much warmer than average, in the highest 10 percent of historical observations, across a wide area for a prolonged period. Strong to severe marine heat waves are occurring in the Atlantic, much of the Pacific, the western and eastern Indian Ocean, and in the Mediterranean Sea.

In October, ocean temperatures at that high threshold covered more than a third of the planet. On the other end, less than 1 percent of the planet had ocean temperatures in the lowest 10 percent of historical values.

Warm and cold ocean temperature extremes should more closely offset each other. But what’s happening is a clear demonstration that oceans, where heat accumulates fastest, are absorbing most of Earth’s energy imbalance. Warm extremes are greatly exceeding cold ones.

That’s a problem because what happens in the ocean doesn’t stay in the ocean.

Because ocean water covers more than 70 percent of Earth, what happens there is critically important to temperatures and humidity on land, with coastal heat waves sometimes fueling terrestrial ones. Weather systems can sometimes linger, producing persistent sunny and wind-free days and bringing ideal conditions for marine heat wave development. These systems can sometimes straddle the land and the ocean, leading to a connected heat wave and transporting humidity.

Trenberth said increasing heat in the oceans, particularly the upper 1,000 feet, is a major factor in the relentless increases in average surface temperatures around the world.

And changes in ocean heat content can affect not just air temperatures, but sea ice, the energy available to storms and water cycles across the planet.

Research has begun to unpack what else may be triggering such changes in global heat.

One recent study found that a reduction in air pollution over the world’s oceans may have contributed to 20 to 30 percent of the warming seen over the North Atlantic and North Pacific, said Andrew Gettelman, a scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the study’s lead author.

Restrictions on sulfur content in the fuels used by shipping liners, put in place in 2020, have dramatically reduced concentrations of sulfur dioxide particles that tend to encourage cloud formation. Though it means lower pollution levels, with fewer clouds, more solar radiation is hitting the oceans and warming them.

A study released Tuesday found that a decline in cloud cover likely contributed to perhaps 0.2 degrees Celsius in previously unexplained warming that hit the planet last year. Goessling and colleagues think that was the product of cleaner shipping emissions, as well as a positive feedback loop in which warming close to Earth’s surface leads to reduced cloud cover, which leads to even more warming.

The study found that in 2023, planetary albedo — the amount of sunlight reflected back into space by light-colored surfaces including clouds, snow and ice cover — may have been at its lowest since at least 1940.

There have also been questions about the roles other factors may be playing, such as an increase in stratospheric water vapor after a 2022 volcanic eruption.

But Earth’s systems are so complex that it’s been impossible to parse what exactly is happening to allow the surge in global temperatures to persist for so long.

“Is this just a blip, or is this actually an acceleration of the warming?” Gettelman said. “That’s the thing everyone is trying to understand right now.”

This year is widely expected to be the warmest year on record, driven largely by the huge stores of ocean heat.

And for now, seasonal model guidance keeps the foot on the accelerator into early 2025, as far as widespread warmer-than-average seas go.

Because of record ocean heat and global temperatures, atmospheric circulation patterns, jet streams and storm tracks across the planet will change. Temperature records will continue to be set.

How big these changes are partly depends on how much warming occurs in the year ahead. But that is unclear because the cooling that usually follows El Niño still hasn’t arrived.

.webp)

It’s possible that normal planetary variations are playing a bigger role than scientists expect and that temperatures could soon begin to drop, said Hausfather, who also works for the payments company Stripe.

Even without the cooling influence of a La Niña, a stretch under neutral conditions, with neither a La Niña nor an El Niño, should mean some decline in global average temperatures, he said.

At the same time, if this year’s unusual planetary warmth doesn’t slow down into 2025, there would be nothing to prevent the next El Niño from sending global temperatures soaring — the starting point for the next El Niño would be that much higher. Whether that happens later in 2025 remains to be seen.

But the lack of clarity isn’t a promising sign when some of the most plausible explanations allow for the most extreme global warming scenarios, Hausfather said.

“The fact that we don’t know the answer here is not necessarily comforting to us,” he said.

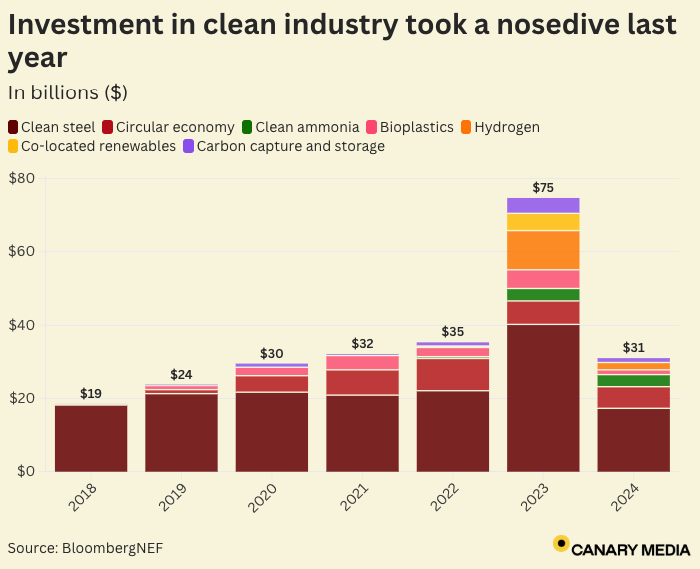

Canary Media’s chart of the week translates crucial data about the clean energy transition into a visual format.

Global investment in efforts to decarbonize heavy industries totaled just $31 billion in 2024, marking a tough year for areas including hydrogen-based steelmaking and carbon capture and storage.

Money for clean industry–related projects fell by nearly 60% last year compared with 2023 — even as investment in the broader energy transition grew to a record $2.1 trillion in 2024, per BloombergNEF.

The diverging outcomes reflect a “two-speed transition” emerging in markets around the world, according to the research firm. The vast majority of today’s energy-transition investment is flowing to more established technologies, such as renewable energy, electric vehicles, energy storage, and power grids.

Meanwhile, efforts to slash planet-warming emissions from heavy industrial sectors — including steel, ammonia, chemicals, and cement — continue to face more fundamental challenges around affordability, maturity, and scalability.

Clean steel projects took the biggest hit in financial commitments, with investment falling to around $17.3 billion in 2024, down from $40.2 billion the previous year, BNEF found.

The category includes new furnaces that can use hydrogen instead of coal to produce iron for steelmaking. Green hydrogen made from renewables remained costly and in scarce supply, leading producers like Europe’s ArcelorMittal to delay making planned investments in hydrogen-based projects. Electric arc furnaces — which turn scrap metal and fresh iron into high-strength steel using electricity — are also considered clean steel projects. Mainland China saw a sharp decline in funding for new electric furnaces as steel demand withered among its automotive and construction industries.

Investment held flat in 2024 for new facilities that use “low-emissions hydrogen” instead of fossil gas to produce ammonia, a compound that’s mainly used in fertilizer but could be turned into fuel for cargo ships and heavy-duty machinery. However, funding declined last year for circular economy projects that recycle plastics, paper, and aluminum, as well as for bio-based plastics production.

BNEF found that, unlike in 2023, few developers of new clean steel and ammonia facilities allocated capital for “co-located” hydrogen plants and renewable energy installations. Likewise, fewer commitments were made to install carbon capture and storage units on polluting facilities like cement factories and chemical refineries.

Whether these investment trends will continue in 2025 depends largely “on a few crucial policy developments in key markets,” Allen Tom Abraham, head of sustainable materials research at BNEF, told Canary Media.

In the United States, companies are awaiting more clarity on the future of federal incentives for industrial decarbonization. The Biden administration previously directed billions of dollars in congressionally mandated funding to support cutting-edge manufacturing technologies and boost demand for low-carbon construction materials — money that is now entangled in President Donald Trump’s federal spending freeze.

Investors are also watching to see what unfolds this month in the European Union. Policymakers are poised to adopt a “clean industrial deal” to help the region’s heavily emitting sectors like steel, cement, and chemicals to slash emissions while remaining competitive. And in China, the government is drafting new rules aimed at easing the country’s overcapacity of steel production, which could impact the deployment of new electric arc furnaces.

“Positive developments on these initiatives could boost clean-industry investment commitments in 2025,” Abraham said.

The recent cancellation of a Massachusetts networked geothermal project isn’t dampening enthusiasm for the emerging clean-heat strategy.

National Grid said this month it has abandoned a planned geothermal system in Lowell, Massachusetts, due to higher-than-expected costs. The news disappointed advocates who see networked geothermal as an important tool for transitioning from natural gas heat, but they pointed to many more reasons for optimism about the concept’s momentum.

The nation’s first utility-operated neighborhood geothermal network, a loop serving 36 buildings in the Massachusetts city of Framingham, is performing well and seeking to expand. It’ll soon be joined by a surge of pilot projects being developed across the country, testing different models and accelerating the learning curve. And a recent report forecasts as much as $5.2 billion in potential savings from leaning more heavily on geothermal energy than on air-source heat pumps.

“This is very promising,” said Ania Camargo, associate director of thermal networks for the Building Decarbonization Coalition. “Networked geothermal makes a lot of sense as a transition strategy.”

The idea for utility-operated networked geothermal systems, often also referred to as thermal energy networks, originated in Massachusetts. The concept grew out of conversations about the environmental and public health dangers posed by aging and increasingly leaky natural gas pipes.

In 2014, the state passed a law requiring gas companies to create plans to replace these leaky pipelines. These plans, however, are projected to cost nearly $42 billion to execute. Climate advocates began to question the wisdom of investing so much money in fossil fuel infrastructure when state policy was simultaneously pushing for electrification and renewable energy. At the same time, air-source heat pumps were catching on, a growing trend that would leave fewer and fewer gas consumers to foot the bill for pipeline repairs.

In 2017, Massachusetts clean energy transition nonprofit HEET proposed a solution: networked geothermal. The systems would be based on well-established geothermal technology, which circulates liquid through pipes that run deep into the ground, extracting thermal energy from the earth and carrying the heat back up to warm buildings. The same principle can provide cooling as well, transporting heat away from buildings and returning it to the ground.

Thermal energy networks scale up the process, connecting many buildings to one geothermal loop, allowing heating and cooling to be delivered to homes in much the same way gas and electricity are. At the same time, they offer a new business model for gas utilities grappling with states’ efforts to transition away from fossil fuels. Utilities liked the idea and jumped on board.

In 2023, the first two such systems broke ground in Massachusetts: National Grid launched one in Lowell, and Eversource began work on a system in Framingham.

The University of Massachusetts Lowell, which was a partner in National Grid’s now-canceled project, hopes to use the engineering and design work developed for the project as the basis for a future network, said Ruairi O’Mahony, senior executive director of the university’s Rist Institute for Sustainability and Energy.

Even the cancellation provides valuable insight by providing a case study of what didn’t work, said Audrey Schulman, executive director of HEETlabs, a climate solutions incubator that spun off from HEET. In this case, the problems included participating homes spread too far from each other and issues with the field where the boreholes were to be drilled. “We’re on an even better arc,” Schulman said. “If there’s a mistake made, we have to correct for it. We can’t have people paying for things that cost too much.”

Meanwhile, the Framingham network began hooking up its first customers in August 2024 and now has about 95% of its anticipated load up and running, said Eric Bosworth, clean technologies manager for Eversource. The system is performing well, keeping customers warm even when a recent cold snap dropped temperatures down to 6 degrees Fahrenheit, he said.

Plans are already underway to expand the system. The U.S. Department of Energy in December awarded Eversource, the city of Framingham, and HEET a $7.8 million grant to develop a second geothermal loop to be connected to the first network, in the process generating valuable information about expanding and interconnecting geothermal systems. The grant is still under negotiation with the federal agency, so it is unclear what the final terms will be. Still, Eversource hopes to have the second system installed in 2026.

“What we’re trying to prove out with Framingham 2.0 is, as we expand on an existing system, that we can do it more efficiently and bring down that cost per customer,” Bosworth said.

The widespread interest in networked geothermal systems within Massachusetts and throughout the U.S. is also promising, Camargo said. In Massachusetts, National Grid is continuing work on a different geothermal network pilot serving seven multifamily public housing buildings in the Boston neighborhood of Dorchester. Last year, HEET, with support from the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, awarded $450,000 in grants to 13 communities to conduct geothermal feasibility studies. And a climate law passed in Massachusetts last year authorizes utilities to undertake networked geothermal projects without getting specific regulatory approval to veer out of their natural-gas lane.

New York has also embraced the idea with enthusiasm. In 2022, the state enacted a law allowing utilities to develop geothermal networks and requiring regulators to come up with guidelines for these new systems. So far, 11 projects have been proposed using a variety of approaches that will provide takeaways for the developers of future geothermal networks, Camargo said.

“New York is amazing,” she said. “They’re doing things in different ways to innovate.”

Across the country, between 22 and 27 geothermal networks have been proposed to utility commissions in Colorado, Maryland, Minnesota, and other states, she said. Eight states have passed legislation supporting utility construction of thermal energy networks, according to Building Decarbonization Coalition numbers, and another four or five are expected to file bills this year, Camargo said.

A report prepared by Synapse Energy Economics for HEETlabs and released last month concludes that geothermal networks offer significant financial benefits when compared with using air-source heat pumps. The analysis found that each system roughly the size of the Framingham network could generate from $1.5 million to $3.5 million in economic benefits, including avoided transmission and distribution costs from lowering peak demand. If 1,500 geothermal networks came online in Massachusetts, the savings could hit $5.2 billion, the analysis calculates.

These savings could be used to subsidize building retrofits, making the homes and offices connected to a geothermal network highly energy efficient to optimize the impact of the ground-source heat pumps, Schulman said.

Even with gathering momentum, challenges remain to the widespread adoption of geothermal networks.

Retrofitting buildings on the network is perhaps the thorniest, particularly in the Northeast where much of the building stock is older and draftier, said both utilities and advocates. In Framingham, an individual efficiency plan had to be created for each home and structure on the loop, a time- and money-consuming process. Going forward, a more streamlined, standardized procedure will likely be necessary, Camargo and Bosworth both said.

“Utilities have not traditionally worked inside the building, so who does it and who pays for it is something that still needs to get worked out,” Camargo said.

Cost is another concern, as the terminated Lowell project demonstrates. However, costs are likely to come down as engineers and installers gain experience in the process and develop smoother supply chains, Schulman said. The second loop planned for Framingham is already likely to be half the amount of the initial system, she said.

As these challenges are worked through, it is vital for Massachusetts to approach its role as a leader in geothermal networks with care, Schulman said.

“We need to think ahead and do this in an efficient and thoughtful way and show the country how it can be done,” she said.

The city of Minneapolis is retooling a decade-old partnership with its gas and electric utilities in response to criticism that it hasn’t done enough to help the city reach its climate goals.

The Clean Energy Partnership was established in 2014 as part of the city’s last round of utility franchise agreements with Xcel Energy and CenterPoint Energy. The agreements authorize utilities’ use of public right-of-way, often in exchange for fees or meeting other terms or conditions from the city.

A little over a decade ago, Minneapolis was among the first U.S. cities to view utility franchise agreements as a potential tool to leverage for climate action. Some advocates at the time had been pressuring the city to study creating a municipal utility to accelerate clean energy, and the partnership emerged as a compromise to give the city more say in the utilities’ operations.

Former City Council member Cam Gordon, who represented southeast Minneapolis in 2014 when the council approved the partnership, is one of the critics who say the initiative “never realized its potential.” Instead, it mainly served as “a government relations and promotional PR tool to allow [elected officials] and the utilities to feel like we’re doing something,” he said.

The City Council is set to approve new franchise agreements this week, and they include an updated memorandum of understanding for the Clean Energy Partnership that will require regular reporting on key performance indicators, new utility-specific emission goals, energy conservation, and service reliability in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Spokespeople for both companies said they welcome the planned changes and that the agreement reflects their interest in working with city leaders on shared clean energy goals.

Since the partnership went into effect in 2015, it has brought together representatives of the utilities, the City Council, and the mayor’s office once per quarter to talk about efforts to reduce emissions in the city. Clean energy advocates and other stakeholders sit on an advisory committee but do not have a formal seat on the partnership’s governing board.

Minneapolis City Council Vice President Aisha Chughtai, who represents the council on the partnership board, expressed frustration about the lack of follow-through from utilities. “Sitting in a meeting and nodding along is one thing. Changing your actions is another,” she said.

By the partnership’s own measures, it has failed to make significant progress on five out of the city’s seven major climate goals. The city is on track with its target to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions from municipal operations but behind pace with its goals related to citywide, residential, commercial, or industrial emissions.

Going forward, the partnership board will continue to meet quarterly, but instead of revolving around city climate goals, each utility will be expected to hit specific targets within Minneapolis’s borders. CenterPoint will commit to reducing emissions from natural gas use by at least 20% by 2035 compared with 2021.

“I think it’s progress,” said council member Katie Cashman, who represents an area west of downtown. The gas utility’s target is “a very meager, insufficient goal, but it is a goal nonetheless, and they haven’t done this in any other city.”

CenterPoint agreed to send a more senior executive to attend the quarterly partnership meetings, though Xcel did not. The utilities also rejected the city’s proposal to hire an outside administrator to manage the partnership.

City leaders believe the new agreement does a better job of setting expectations, but Minneapolis will still lack formal leverage over the utilities if they fail to make progress. The agreement does not contain any penalties for failure to follow through, and the next window to renegotiate isn’t until 2035 when the franchise agreement comes back up for renewal.

Luke Hollenkamp, the city’s sustainability program coordinator, said data reported through the partnership allows the city to make course corrections in its climate work.

“We can see what’s working, what’s not working, and also see where we need to invest more time,” he said.

Xcel Energy’s spokesperson said the partnership has led to successes, noting that citywide emissions from electricity have declined and that Minneapolis met its goal of powering city operations with 100% renewable electricity in 2023 by participating in Xcel’s Renewable*Connect program.

CenterPoint said it has invested nearly $61 million in energy efficiency programs in Minneapolis since 2017, saving residents $25 million in energy costs while reducing 245,000 metric tons of emissions. The utility also developed an on-bill financing program advocated by clean energy activists and others.

Despite the partnership’s imperfections, current and former city officials said it’s better to keep it in place as part of the new franchise agreements than to let it dissolve.

“We’re ramping up our trajectory [to cut emissions],” Cashman said. “We’re setting an example of how other cities can lead on climate action.”

The City Council’s climate and infrastructure committee approved the new agreements on Feb. 6; the full council is set to vote on them Feb. 13.

Clean energy installations in the U.S. reached a record high last year, with the country adding 47% more capacity than in 2023, according to new research by energy data firm Cleanview.

Boosted by tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act and the plummeting costs of renewable technologies, developers added 48.2 gigawatts of utility-scale solar, wind, and battery storage capacity in 2024. In total, carbon-free sources including nuclear accounted for 95% of new power capacity built in the U.S. last year; solar and batteries alone made up 83%.

The report finds that developers are not only building more projects but bigger ones, too. In 2024, companies built 135 solar, wind, and storage facilities with 100 megawatts or more of capacity, continuing a trend of clean energy megaprojects around the country.

Despite the growth of renewables, fossil fuels — mostly gas — still generated more than half of the U.S.’s electricity last year. Carbon-free sources including nuclear produced just over 40% of power.

This year, renewables will continue growing but at a slower pace, the report says. Based on developer projections, the U.S. could add 60 GW of large-scale clean power capacity in 2025. That would be a 26% jump from the previous year, but it’s only possible if the industry can maintain momentum despite headwinds from the Trump administration.

Solar led the way last year and is expected to do the same this year.

In 2024, the U.S. added a new record of 32.1 GW worth of utility-scale solar capacity. That’s a 65% increase from 2023, when the country added 19.5 GW of utility-scale solar. Most new solar was built in Texas, which added 8.9 GW worth of the clean energy source, followed by Florida, which built 3 GW and outpaced California for the first time. Arkansas, Missouri, and Louisiana each saw rapid growth in solar, adding hundreds of MW of capacity where relatively little existed before.

Developers expect to add 33 GW of utility-scale solar to the grid in 2025, which would represent a 3% year-on-year growth, the report finds. The U.S. Energy Information Administration, meanwhile, said in late January that it expects solar installations to decline to 26 GW this year.

Continued progress for solar — and for any clean energy deployments — will depend heavily on the Trump administration.

President Donald Trump has already stalled clean energy and infrastructure projects nationwide by attempting to halt hundreds of billions of dollars in congressionally authorized funding — a move that experts say is illegal and has been struck down by federal courts. Some Republican members of Congress have also threatened to roll back clean energy tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act that are key to enduring growth in the renewables sector.

For utility-scale solar, “uncertainty around the Trump administration’s energy agenda and the future of the IRA will cause the segment to stagnate, despite extremely high demand from data centers,” analysts at Wood Mackenzie wrote in January.

The political picture is even more grim for the U.S. wind sector, which has already seen years of declining installations and now faces relentless attacks from Trump.

For several years now, the wind industry has faced challenges including a lack of long-distance transmission lines to transport electricity from far-flung areas in the middle of the country to urban centers. Supply chain woes and inflation have also led to a spate of canceled offshore wind projects in the Northeast.

In 2024, the U.S. added 5.1 GW of utility-scale wind, including its first commercial offshore wind farm, marking a 23% drop from 2023 and the fourth year in a row of falling annual installations. Texas alone accounted for 42% of the country’s new wind capacity in 2024, bringing 2.1 GW online.

Developers expect to add 9.2 GW of wind capacity this year, and 6.1 GW are already under construction or waiting to come online, according to the Cleanview report. If that happens, wind capacity additions would increase by 79% this year.

But that’s a big if. Trump has vowed that “no new windmills” will be built during his presidency and has taken aim at offshore wind in particular — a sector that on paper is set to give wind installations a big boost this year. It remains to be seen whether these under-construction projects will be able to forge ahead as planned despite political headwinds.

Battery storage could be more of a bright spot. Its growth, already fast, is set to accelerate this year.

Last year, the U.S. added 10.9 GW of battery storage capacity, a 65% year-on-year increase that surpassed the previous 56% leap in 2023. California and Texas brought the most grid storage online, building 3,152 MW and 2,832 MW of capacity respectively.

In 2025, storage developers expect to add 18.1 GW of capacity, which would equal a 68% jump from 2024. Based on projections, Texas will overtake California as the nation’s leading energy storage market by adding 7 GW of capacity this year, Cleanview found.

The battery buildout has been propelled in part by declining prices, but even energy storage hasn’t escaped Trump’s assault on renewables. The administration’s tariffs on Chinese imports are expected to negatively impact the industry, which relies on batteries manufactured in China.

As the Trump administration attempts to block billions of dollars in federal funds for electric vehicle charging, an Illinois utility is moving forward with a massive investment to promote wider EV adoption.

At a press conference last Thursday ahead of the 2025 Chicago Auto Show, ComEd announced $100 million in new rebates designed to boost EV fleet purchases and charging stations across northern Illinois. The program helps meet the mandate for the state’s Climate and Equitable Jobs Act, which calls for 1 million EVs on the roads by 2030.

Of the $100 million, $53 million is available for business and public-sector EV fleet purchases, while nearly $38 million is designated to upgrade infrastructure for non-residential charger installations. An additional nearly $9 million is intended for residential charging stations.

The money is in addition to $87 million announced last year for similar incentives.

Funding for the rebate programs comes from distribution charges and “has nothing to do” with the federal government, Melissa Washington, senior vice president of customer operations and strategic initiatives at ComEd, said during an interview. This means that there is no risk of withholding or reductions from the Trump administration.

Washington anticipates continued high levels of interest and engagement in the programs.

“Based upon what we saw last year, there was a quick demand. Applications came right away the minute we opened it up. I would imagine people will be going on [ComEd’s website] and immediately trying to see what we have available for them,” Washington said.

Since launching its EV rebate program last year, ComEd has funded projects in more than 300 ZIP codes, including nearly 3,500 residential and commercial charging ports, and provided funding for municipalities, businesses, and school districts to purchase more than 200 new and pre-owned EV fleet vehicles. The utility designated more than half the available rebate funds for low-income customers and projects in environmental justice communities.

ComEd also partners with the Chicago-area Metropolitan Mayors Caucus on the EV Readiness Program, which helps local governments create ordinances and safety and infrastructure plans to accommodate the growing demand for EVs in their communities. Since its initiation, more than 41 northern Illinois municipalities have participated in the program.

The importance of utility funding for the rebate programs was highlighted by Susan Mudd, senior policy advocate for the Environmental Law and Policy Center, who noted that a St. Louis-area school district is still waiting on 21 electric school buses that had been promised and ordered. The district has been unable to access the online portal to receive its federal funding, due to an executive order issued by the Trump administration.

“During the last four years, the federal government was a reliable partner with policies and programs that helped propel electric vehicle production and implementation and updated standards to save consumers money while cleaning up the air,” Mudd said at the press conference. “That order has already meant that students who would already be riding quiet zero-emission buses are still on old, dirty diesel ones, and the business that was to deliver them can’t get paid.

“While the new administration is willing to sacrifice the health of people across the U.S. and the world, thankfully, we in Illinois can continue to improve things,” Mudd said.

Canary Media’s Electrified Life column shares real-world tales, tips, and insights to demystify what individuals can do to shift their homes and lives to clean electric power.

Andrew Garberson isn’t worried about his electric vehicle handling cold winters.

He recently drove his EV to the gym when the temperature where he lives in Des Moines, Iowa, was a biting 4 degrees Fahrenheit. A polar vortex had brought a brutal wind, “the kind that whistles in the cracks of the car doors when you drive.”

Garberson relies on his electric truck, a graphite-gray Rivian, for year-round family road trips to see his parents, who live a few hours away. “My car will drive 200 miles in freezing conditions in the Midwest,” said the head of growth and research at Recurrent, a company that aggregates data on battery health from more than 29,000 EVs across the United States.

Switching from a gas car to an EV is one the biggest actions an individual can take to reduce their emissions. But EVs have gotten something of a bad rep in cold weather. It’s true that they, like gas cars, lose range as temperatures fall: Depending on the EV, the drop can be 16% to 46%. That loss may be anxiety-provoking, especially for EV owners-to-be.

From Garberson’s perspective, the criticisms are overblown. EVs work even in the most bone-chilling climates across the continental U.S., he said. In any case, Recurrent has found that knowledge and experience go a long way toward relieving those fears.

Plenty of frosty regions are embracing electric cars. Just look at Chicago. Despite its freezing winters, it’s one of the top cities for EV registrations, with more than 25,000 in the 12 months ending in June 2024, according to Experian’s most recent available data. Outside the U.S., the trend holds, too: In Norway, where temperatures can drop below -4˚F, nearly 9 out of 10 new cars sold in 2024 were fully electric.

In this article, we’ll dive into how to get the most winter range out of an EV. First up is a key EV feature to look for if you’re still shopping. Then, for those who already have an electric car, Garberson shares his top range-extending strategies.

EV range shrinks in the cold partly because the chemical reaction in their massive lithium-ion batteries slows down. But the biggest reason for winter range decline is the need to keep passengers warm, Garberson said.

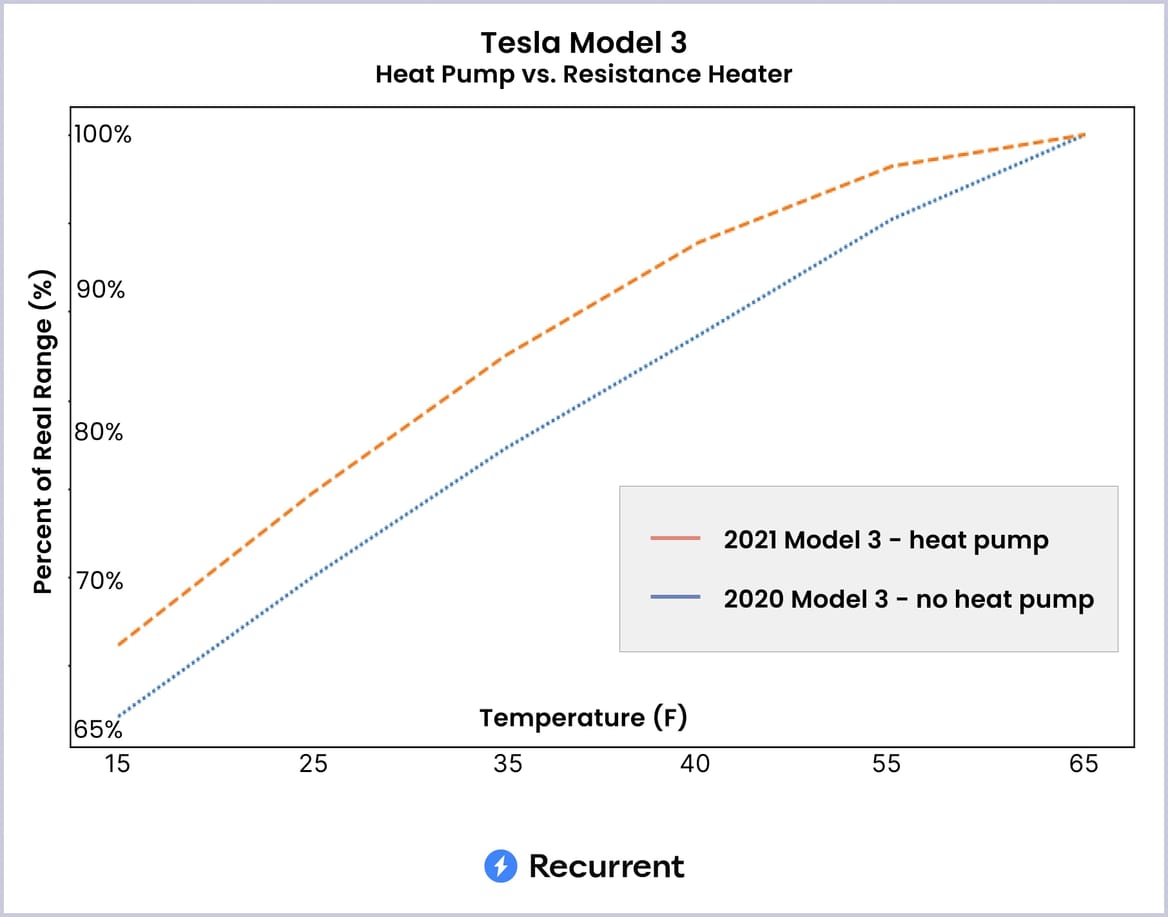

Gas cars use the waste heat generated from the internal combustion engine for cabin heating. EVs don’t have an engine (they have a motor), so they don’t produce enough accidental heat to keep occupants cozy in frigid weather. Instead, EVs siphon energy from the battery to heat the cab, leaving less for propulsion. EVs can either make heat with an electric-resistance heater, which is like turning on a toaster, or much more efficiently move heat from the outdoors into the car using a heat pump.

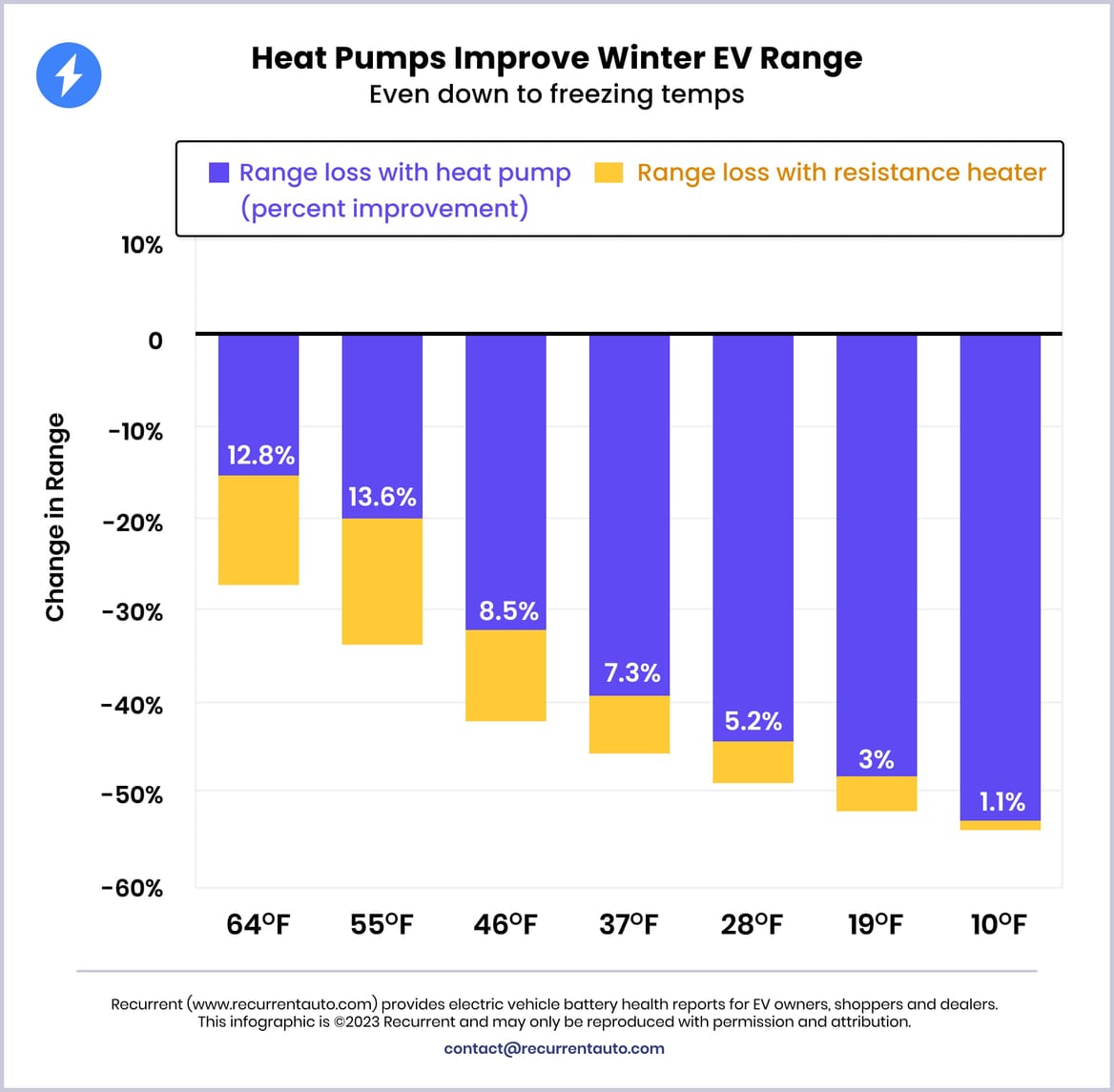

Heat pumps are famous for their critical role in decarbonizing space heating in buildings. They don’t burn fossil fuel, and they’re typically two to three times as efficient as gas and electric-resistance systems, even below freezing. But the tech has also made its way into clothes dryers and water heaters. Now found in some EVs, heat pumps improve range by 8% to 10% in cold conditions, according to Recurrent.

According to Recurrent’s analysis, electric vehicles with the best winter range tend to have heat pumps, including the Tesla Models X, S, 3, and Y; Audi e-tron; and Hyundai Ioniq 5 and Kona.

It’s worth pointing out that heat pumps themselves are less effective as temperatures drop. Even so, EVs with heat pumps offer better range than those with electric-resistance heating. Recurrent points out that at 55˚F, a heat pump reduced range by 20% while a resistance heater lowered it by 33%. As the weather gets colder, the difference in range between EVs with heat pumps and those with resistance heaters shrinks.

To be clear, EVs work well in the winter even without heat pumps, Garberson said. His Rivian truck doesn’t have one, and on a day-to-day basis, he doesn’t even notice the decline in range. He charges at home, which makes topping up easy. For longer road trips, cold weather might mean he needs one more charging stop than he normally would.

Heating technology aside, drivers can take steps to get more out of their EVs in the cold. Recurrent’s Garberson offered his top three range-saving strategies for winter EV drivers.

Prewarm your EV while it’s plugged in. Garberson’s garage isn’t climate-controlled, so his vehicle gets chilly when the weather does. About 10 minutes before he hops in, he uses his car’s app to warm up the cabin. Pulling electricity from the wall outlet means he won’t have to use the battery to bring his car from 4˚F to a toasty 70°F.

Set your charging limit higher. Batteries are happiest when balanced at 50% charge, Garberson said. Because huge charge-level swings are harder on the battery, Recurrent recommends keeping it between 20% and 80% full. But “let’s eliminate anxiety from the discussion and just charge cars a bit more in cold conditions,” he advised. If you normally charge to 70% to keep the battery healthy, as Garberson does, increase it to 80% in the winter.

When you’re headed to a fast charger, set the destination in the car’s GPS, a feature in most modern EVs. Letting the EV know will allow it to start preconditioning the battery so it’s ready to charge when you get there. Otherwise, you may need to wait 15 to 20 minutes at the charger for the battery to warm up sufficiently, Garberson said. “It’s just amazing how [electric] vehicles have been designed over the last few years to help drivers without them even knowing.”

One more tip for your kit? Turning on the heated steering wheel and heated seats “is a far more efficient way” to warm yourself and passengers than heating up the air in the car’s cabin, Garberson said. Once the car is prewarmed and you’re on the road, you could dial down the thermostat and use the targeted heat features to keep you cozy.

But most importantly, Garberson added, do what you need in order to keep yourself and your passengers happy. He’s father to a one-year-old, so “relying on heated seats is not part of my driving equation.”

Besides, “I will admit I am kind of a sucker for creature comforts,” Garberson said. “I need heat any way I can get it.”

Manufacturers provide even more advice on how to extend the winter range of your particular EV model, so be sure to check out their online guides.

A little planning and know-how can go a long way toward a smooth EV experience in frosty weather, Garberson said. Winter takes a bite out of his EV’s range, yes, but “I get by just fine.”

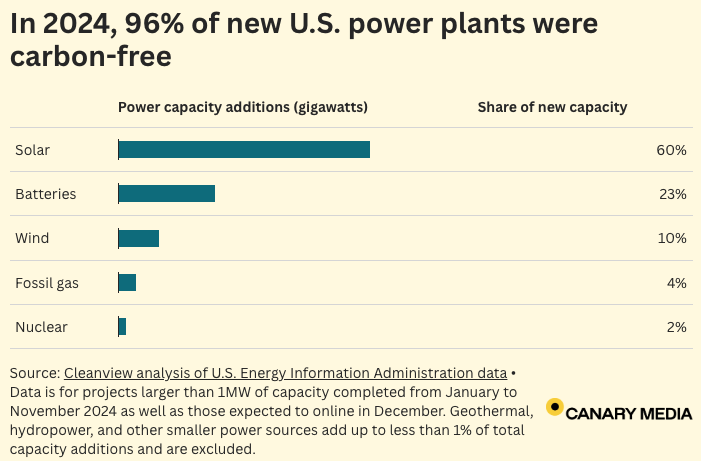

Canary Media’s chart of the week translates crucial data about the clean energy transition into a visual format.

The amount of carbon-free energy built in the U.S. last year far eclipsed the growth of new fossil-fueled power plants.

The U.S. grid added a total of just over 56 gigawatts of power capacity last year. A whopping 96 percent of that came from solar, battery, wind, nuclear, and other carbon-free installations, per new Cleanview analysis of U.S. Energy Information Administration data.

Solar installations dominated power plant additions — 34 gigawatts of utility-scale solar were constructed across the U.S., a 74 percent jump from 2023’s record-high year. Texas and California drove most of this surge.

Grid batteries were the next-biggest new source of power capacity — and saw the fastest growth. The U.S. built 13 GW of energy storage last year, almost double 2023’s record-shattering 6.6 GW. Texas and California led the way here as well.

Wind was the third-biggest source of new capacity, but installations dropped for the fourth year in a row as the industry continued to struggle through lingering supply-chain issues, a plodding interconnection process, and local opposition to projects. Just 2.4 GW of new gas and 1 GW of nuclear went online in 2024.

The U.S. has rolled out more clean energy than fossil-fueled power plants for years now, helping the grid get cleaner and less carbon-intensive. Power emissions have fallen steadily since peaking in 2007 as fossil gas and renewables have replaced coal.

Still, fossil fuels generate the majority of the country’s power and the U.S. faces an uphill battle to decarbonize its grid by 2035, a goal set by outgoing President Joe Biden.

Fossil gas is currently the top source of electricity generation in the U.S., and last year emissions from its use in the rose nearly 4 percent. As big tech firms look to build more energy-intensive data centers to support their AI goals, the sector could become even more reliant on fossil fuels. That surging power demand is already extending the life of coal plants and causing utilities to propose building more gas-fired power plants.

In order to eliminate carbon emissions from the grid, the U.S. is going to need to figure out how to build enough clean energy to dethrone fossil fuels. That was a hard task even when Biden was president and before the AI-driven electricity boom took hold. It will be an even taller task under incoming President Donald Trump, who has vowed to double down on fossil fuels.

The Trump administration has declared that it is rescinding guidance for a $5 billion program that funds EV-charging installations nationwide, potentially halting states’ plans to put billions of obligated but as-yet unspent dollars to work. It’s the new administration’s latest attack on federal climate and clean energy programs authorized by Congress during the Biden administration, and like the others, it’s almost certain to be challenged in court, experts say.

The unexpected news came in a Thursday memo from the Federal Highway Administration to state transportation departments responsible for managing the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program. NEVI was created by the bipartisan infrastructure law passed by Congress in 2021 to establish reliable charging along major highways across the country. The program is structured to guarantee states access to funds under federally approved plans through fiscal year 2026.

The memo states that FHWA is “immediately suspending the approval” of these state plans pending a U.S. Department of Transportation review. States’ “reimbursement of existing obligations will be allowed in order to not disrupt current financial commitments,” the memo notes. But “no new obligations may occur” until new guidance is developed and states submit and receive approval for their updated plans — a process that could last through the rest of this year.

The memo’s instructions conflict with longstanding practice of guaranteeing states access to federal highway spending as well as with the structure of the NEVI program set by Congress in the infrastructure law.

“Freezing these EV charging funds is yet another one of the Trump administration’s unsound and illegal moves,” Katherine García, Sierra Club’s clean transportation for all director, said in a Friday statement. “This is an attack on bipartisan funding that Congress approved years ago and is driving investment and innovation in every state, with Texas as the largest beneficiary.” The Lone Star State is slated to receive nearly $408 million from the program.

Of the $5 billion authorized by NEVI, $3.27 billion has been obligated to all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, according to EV-charging data firm Paren. Of that, roughly $615 million is under contract for constructing almost 1,000 charging sites, Loren McDonald, Paren’s chief analyst, said in a webinar last month.

In a Thursday email, McDonald highlighted that “companies that are under contract with a state and have incurred expenses will get reimbursed.” At the same time, “the experts in Washington, D.C., that we have spoken to in the last few months believe that changes in NEVI like this would require a change in the law from Congress.”

“Our understanding is that FHWA does not have the authority to actually halt or revise the NEVI program this extensively, but will move forward, creating havoc for several months until lawsuits, the courts, and Congress resolve it,” he wrote.

Under the Biden administration, NEVI program formula funding was allocated through fiscal year 2026, and FHWA had approved states’ annual spending plans through fiscal year 2025, Kelsey Blongewicz, policy analyst at research firm Atlas Public Policy, told Canary Media last month.

That funding is “tied to approved state plans and contracts that makes it nearly impossible to reverse or stop,” Beth Hammon, senior EV infrastructure advocate at the Natural Resources Defense Council, wrote in a blog post last month.

Still, FHWA’s new instructions “create great uncertainty for the billions of dollars states and private companies are investing in the urgently needed infrastructure to support America’s highway transportation network,” Ryan Gallentine, managing director at Advanced Energy United, said in a Thursday statement. The trade group represents EV manufacturers, charging infrastructure developers, and other companies involved in NEVI-funded projects.

“States are under no obligation to stop these projects based solely on this announcement,” he wrote. “We call on state DOTs and program administrators to continue executing this program until new guidance is finalized.”

President Donald Trump attacked EVs and the NEVI program on the campaign trail. His administration issued an executive order within hours of his inauguration demanding a halt to all Biden-era climate and clean energy spending and singled out the NEVI program for scrutiny.

Federal agencies have since halted the flow of tens of billions of dollars of federal climate and clean energy funding, drawing outrage from state agencies, nonprofit groups, and companies that have been unable to recover money already spent on projects and programs. Two federal judges have responded to lawsuits challenging the freeze by issuing court orders demanding a halt to them, but a multitude of programs remain inaccessible, according to reports from grant recipients.

Confusion over the NEVI program’s future comes at a moment when significant investments are starting to flow from states to EV-charging manufacturers and charging-network providers — including Tesla — after years of bureaucratic and administrative delays. Federal data as of November tracked 126 operational public charging ports at 31 sites built using NEVI funding.

The Biden administration hoped to spur the buildout of 500,000 public charging stations by 2030, up from about 206,000 today. The NEVI program wasn’t intended to build all those chargers itself but to help install them in places where the economics of providing EV charging aren’t yet supported by the number of EVs on the road, McDonald said.

“In many states, the NEVI program helped jumpstart investment in high-speed EV charging stations, getting high-speed chargers at the gas stations and truck stops where millions of drivers already stop every year,” Ryan McKinnon, spokesperson for Charge Ahead Partnership, a trade group representing fueling-station owners and convenience store chains that make up the majority of NEVI charging sites, said in a Friday statement. “Other states dragged their feet.”

According to McDonald, since NEVI was singled out by the Trump administration, six states have indefinitely discontinued work on it, including Ohio, the Republican-led state that installed the program’s first live chargers in 2023.

UPDATE: In a Friday email, an FHWA spokesperson stated the agency is “utilizing the unique authority afforded under the NEVI Formula Program to ensure the Program operates efficiently and effectively and aligns with current U.S. DOT policies and priorities.”

Massachusetts’ attorney general says plans by the state’s major utilities to lower the cost of charging electric vehicles would offer little actual savings for customers.

In response to a 2022 Massachusetts climate law, the state’s two primary electric utilities, Eversource and National Grid, have proposed plans to create lower rates for charging EVs during off-peak hours, which they say would be implemented no sooner than 2029.

In a regulatory filing last week, however, the state’s attorney general said the utilities’ estimated savings for customers are based on faulty calculations and would be much lower in reality. Plus, a requirement that households and small businesses pay for additional meters to track their charging stations’ power use “negates all financial value for the customer.”

With this filing, the attorney general’s office joins climate advocates who support the idea of offering EV drivers the chance to save money by charging during off-peak hours but take issue with the way utilities propose to implement the strategy.

“If you require that people install a second meter and that they cover the cost of that installation, nobody’s going to do it,” said Anna Vanderspek, electric vehicle program director at the Green Energy Consumers Alliance.

Regulators have asked the utilities for feedback on the attorney general’s concerns and recommendations by February 20. A spokesperson for Eversource did not specifically address the attorney general’s criticism when asked about it but said the utility believes in the benefits of time-of-use pricing and looks forward to continuing the regulatory process. National Grid did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

More than a third of cars sold in the United States are likely to be EVs by 2030, J.D. Power forecasts, a prospect that has many industry and elected leaders wondering whether the country’s electric infrastructure is ready to provide power for this growing, gas-free fleet.

Massachusetts has set the ambitious target of putting 900,000 EVs on the road — and on the grid — by 2030. So, like other states facing the same challenges, Massachusetts has turned to the idea of using financial incentives to encourage EV owners to charge during off-peak hours and to lower the cost of charging for drivers in a state where electricity prices are among the highest in the country.

“Electric vehicle time-of-use rates could be a very valuable tool for helping to alleviate the load on the system as well as helping to incentivize people to think about when they’re using electricity,” said Priya Gandbhir, director of clean power at the Conservation Law Foundation.

In the 2022 climate law, legislators required utilities to propose these so-called time-of-use rates, which both Eversource and National Grid did in August 2023.

Eversource’s plan calls for a $15 monthly fee and an off-peak EV charging rate of 19 cents per kilowatt-hour, slightly more than half the proposed peak rate. National Grid would impose a $10 monthly fee and charge 14 cents per kilowatt-hour for off-peak charging, half what the peak rate would be. Both plans would require a separate meter, and both contend the rates cannot be implemented before advanced metering infrastructure is rolled out and tested, a process they expect to take at least four years.

Regulators must rule on these proposals by the end of October.

The numbers laid out by the utilities don’t add up to savings for consumers, the attorney general’s testimony argues. Thus, the proposals are unlikely to motivate more people to buy EVs or to shift their charging times.

The utilities did not estimate the cost of installing a separate meter, but online estimates run from $1,400 to more than $4,000. At the same time, the utilities drastically overstated the savings their plans would yield by using inflated estimates for how many kilowatt-hours the average driver would use to charge their EV, the attorney general’s testimony says. Rather than saving as much as $146 a month, as the utilities calculated, drivers would cut their bill by $21 per month at most, assuming they do all of their charging during off-peak hours. Customers who sometimes charge during peak hours could even see bill increases.

“The math just doesn’t work out,” Vanderspek said.

The attorney general’s office recommends that public utilities regulators reject National Grid and Eversource’s proposals and offers several alternative approaches. The simplest, the testimony says, would be to offer whole-home time-of-use rates, rather than separating out the vehicle charging load. Evidence from other states suggests such a rate could be implemented during the roll-out of advanced metering infrastructure, rather than waiting the minimum of four years the utilities say would be necessary for an EV-specific rate. The filing points to Colorado, where time-of-use rates are rolling out in concert with advanced metering infrastructure.

Another option would be to use data collected by vehicle computer systems or chargers themselves to issue rebates or apply lower rates for charging done at off-peak times. Utilities in California and Minnesota have already deployed this approach.

The same data could be used to offer other financial incentives. National Grid, in fact, already offers such a program in Massachusetts, giving customers 5 cents per kilowatt-hour for off-peak EV charging during the summer and 3 cents per kilowatt-hour the rest of the year.

Any of these approaches could be used not just to improve financial incentives for customers but also to speed up their implementation, to the benefit of both consumers and the environment, Vanderspek said.

“We’re all better off if we’re shifting that load off-peak right now,” she said.