California has big heat-pump dreams. Now, it’s got a road map to realize them.

Last week, the California Heat Pump Partnership announced the nation’s first statewide blueprint to achieve the state’s ambitious goals for deploying heat pumps, a critical tech for decarbonizing buildings and improving public health. The plan draws on recommendations from the public-private partnership’s members, which include government agencies, heat pump manufacturers, retailers, utilities, and other stakeholders.

“We hope it serves as a national model,” said Terra Weeks, director of the partnership.

In 2022, California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) set a goal for the world’s fifth-largest economy to deploy 6 million heat pump units by 2030. That includes heat pumps for building heating and air-conditioning needs as well as for water heating. An estimated 1.9 million have been installed so far, according to the blueprint report.

The state is not on track to hit that 2030 benchmark. Even with current policies and incentives, California would fall 2 million heat pumps short, the report says.

Heat pump units are outselling gas furnaces nationally, but of the roughly 1 million units of HVAC equipment sold annually in California, just one in five are heat pumps. Of about 800,000 water heaters sold each year, only 3% to 5% are heat pump models. The state is one of nine committed to making heat pumps at least 65% of residential HVAC sales by 2030.

Looking beyond the 2030 target, the Golden State ultimately needs to deploy an estimated 23 million heat pumps to decarbonize its residential and commercial sectors by 2045, when California aims to be carbon neutral.

Heat pumps face considerable challenges to mass adoption in the state. Many Californians aren’t aware of the appliance’s benefits, according to the report. Heat pumps are typically more expensive up front than gas furnaces and can cost more to run in states like California where electricity prices are high relative to those of gas. Plus, many contractors aren’t prioritizing heat pumps, citing a lack of market confidence, the report notes.

The blueprint lays out a raft of solutions to make heat pumps more desirable and affordable. Building customer demand and contractor support is key to making them “the easy and obvious choice,” as the report puts it.

To create buzz for the appliances, the partnership is launching a “heat pump week” with interactive experiences next spring. The group will also start a broader marketing campaign this fall, which will include spotlighting contractors who already install heat pumps.

To reduce up-front costs, the coalition supports expanding heat pump financing tools, like the low-interest loans from the State Treasurer’s Office GoGreen Home program. Weeks also underscored the need for incentives that are easy for contractors and customers to access, such as instant, “point-of-sale” rebates for heat pumps.

Applying lessons from existing incentive initiatives like TECH Clean California, the partnership recommends that program architects get input from contractors and manufacturers on how to design incentives and ensure funds follow predictable timelines, rather than abruptly run out.

“The current start-and-stop dynamics that we’re seeing with many incentive programs today … can deter both customers and contractors from opting for heat pumps,” Weeks said. “There’s really broad consensus from our members that there is a distinct need to just make sure that those incentives don’t disappear.”

The group also endorses streamlining the permitting process for heat pump installations, a measure currently before the state Legislature.

The blueprint points out that focusing on particular markets could help supercharge heat pump adoption. Residents in the San Francisco Bay Area, for example, must start replacing their broken gas-fueled furnaces and water heaters with zero-emissions electric equipment starting in 2027 to comply with air quality rules.

Consumers in hotter areas, like inland California, will also save more on cooling costs than other customers when they replace older, less-efficient central ACs with heat pumps, making them potentially prime early adopters.

If heat pumps went from their current 23% of market share for AC replacements to 80%, installations would add up to roughly 1.7 million additional units over six years, per the report.

A linchpin of the blueprint is a workforce advisory council of installers, trade associations, workforce educators, and other stakeholders who can help guide the partnership’s marketing efforts and policy recommendations.

“We need to be designing regulations and programs with contractors so that they work for contractors,” Weeks said. “And if we make it easy and profitable for contractors, we win.”

The sweeping tactics laid out in the report will require substantial funding, potentially in the billions of dollars. But exactly how much will be up for debate, Weeks said. Funds could come from a variety of sources, including cap-and-trade revenues, utility ratepayer programs, and state tax dollars, she said. The report recommends minimizing the use of ratepayer funding; California is looking to cut costs to utility customers as the state’s electricity bills skyrocket.

Last Monday, California paused its $290 million home energy rebate program, part of an $8.8-billion federally funded initiative for heat pumps and other home energy upgrades, because state officials couldn’t access funds.

But Weeks remains sanguine; California runs several home-grown programs, including the $500 million Equitable Building Decarbonization program to put heat pumps in reach for thousands of low-income households.

“While the step back from the federal government on funding programs is regrettable,” Weeks said, “leadership states like California will find ways to help people make the right choice to buy heat pumps.”

Republicans are looking to roll back key electric-vehicle incentives passed under the Biden administration. Doing so would kneecap the EV transition for years to come.

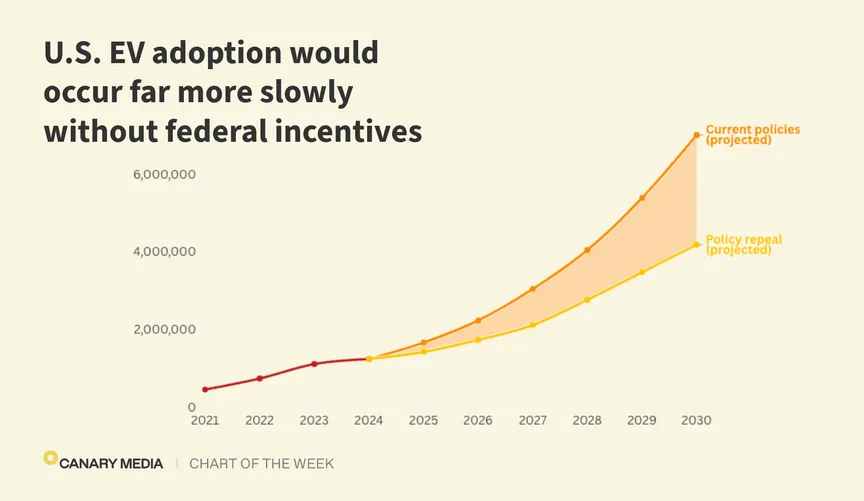

Under current policies, the number of light-duty EVs sold annually is forecast to climb to 7 million by 2030, according to a new analysis from the REPEAT Project at Princeton University. But if those policies — specifically the consumer EV tax credit and tailpipe emissions rules — are repealed, that figure is forecast to be 40% lower in 2030, at around 4.2 million.

Despite Detroit’s pleas, the Trump administration and congressional Republicans are seeking to eliminate the $7,500 EV tax credit as well as vehicle efficiency rules that incentivize automakers to stop making gas-fueled cars.

It would be a blow to a U.S. EV industry that’s already coming off a year of mixed success. On the one hand, consumers bought a record number of EVs in 2024 as models from automakers other than Tesla caught on. On the other hand, sales grew by just 7% compared with the year prior — a sluggish rate compared to the nearly 50% leap that occurred in 2023 — and automakers began walking back from their EV commitments even prior to President Donald Trump’s election.

Should Republicans succeed in repealing the tax credits and efficiency rules, it would further slow EV adoption — and in the process destroy jobs at EV and battery factories. The REPEAT Project analysis found that eliminating these policies would threaten plans to expand U.S. EV factories and potentially lead to the cancellation or closure of half of existing EV factory capacity. The moves would have a similar effect on the burgeoning battery belt.

More than 80% of announced investments in U.S. EV manufacturing are located in congressional districts represented by Republicans, according to a January report from the Environmental Defense Fund and WSP USA.

Beyond the economic ramifications of the potential repeal, the climate consequences are dire. Gas-powered vehicles are one of the largest sources of planet-warming carbon emissions in the U.S.; they also cause a significant amount of smog-forming pollution that can contribute to respiratory diseases like asthma. Slowing down the transition to electric vehicles would only serve to exacerbate these problems.

It is easy to overlook the low-rise, cream-colored building on Chicago’s Motor Row, a historic district that was a hub for auto dealers in the early 1900s.

Yet the newly purchased headquarters for Bronzeville Community Development Partnership at 2416 S. Michigan Ave. plays both a symbolic and substantive role in fulfilling the organization’s mission of promoting clean energy and community-driven development in this predominantly Black, environmental-justice neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side.

“We want to be able to tell the story of the Great Migration and how we are replicating that age of innovation here in the 21st century, with the transition away from fossil fuels to beneficial electrification,” said Billy Davis, general manager for JitneyEV + EVCharge, one of the partnership’s initiatives. “Not just in commerce and transportation but culturally in the arts as well.”

Since its foundation in 1989 as the Abraham Lincoln Center Business Council, BCDP has strived to promote sustainable economic development in Bronzeville.

The Bronzeville Microgrid, which the organization developed in collaboration with utility ComEd, is one of BCDP’s main clean energy initiatives. As Chicago’s first neighborhood-scale system of its kind, the microgrid services more than 1,000 buildings with solar panels, batteries, and fossil gas–fired generators.

Another major initiative, through the JitneyEV + EVCharge program, is to expand EV adoption among Black and Brown drivers to reduce carbon emissions and other pollution, which have been disproportionately concentrated in environmental justice communities.

BCDP also advocates for the construction of public charging stations throughout the city’s South and West sides, where many communities lack access to such infrastructure.

This work, in addition to sustainability-focused development and cultural tourism projects, reflects a holistic approach to mitigating the adverse effects of disinvestment and climate change in environmental justice communities.

“What happens when a community transforms infrastructure, heritage, and innovation from vision to reality? In Bronzeville, 2024 was the year we proved that sustainable development isn’t just a concept—it’s a lived experience,” wrote Paula Robinson, president of BCDP and managing member of Bronzeville Partners LLC, in a January social media post. “This year, we didn’t just talk about change. We powered it—literally and metaphorically.”

BCDP moved into its current headquarters in June 2024 after purchasing the building with a grant from the state of Illinois, which included funding for a solar array and EV charging infrastructure. The organization also received a City of Chicago Climate Infrastructure Fund grant for energy-efficiency improvements to the building. JitneyEV + EVCharge was awarded a grant from that fund for purchasing EVs and installing charging infrastructure, according to Davis.

The complex, which is still being fitted out, includes a garage for JitneyEV; a visitor center and community meeting space; and spaces for the Urban Innovation Center, Innovation Metropolis, Bronzeville Studio, and the Bronzeville-Black Metropolis National Heritage Area, all of which are affiliates of the larger BCDP collective.

Owning the building allows BCDP to bring the various aspects of its work under a single umbrella and eliminates vulnerability to the whims of a landlord. At the same time, the building serves as a tangible symbol of the organization’s focus on self-sufficiency and self-determination, which is especially relevant in the present political environment.

In Motor Row’s heyday in the early 20th century, Chicago was home to multiple electric vehicle companies. And modern app-based rideshare services operate much like jitneys — taxi-like services that flourished in African American communities that conventional taxicabs often refused to serve. BCDP has married the two histories in its JitneyEV + EVCharge program, which aims to provide the community with an all-electric rideshare service and expand access to public EV charging stations.

BCDP recently purchased its first electric vehicle for the rideshare service and plans to purchase an electric passenger van in the future. BCDP also intends to install a public DC fast charging station on the outside of its new headquarters and a Level 2 charger inside the building’s garage for its own vehicles, according to Davis.

“The building that we are in, the building that we own, was once home to electric automobile manufacturing companies at the turn of the 20th century,” Davis said, adding that it housed showrooms for Detroit Electric, Chalmers Motor Co., and Cadillac.

“So, it just resonates somewhat, that we are returning home, so to speak,” Davis said.

Once it is fully operational, JitneyEV’s rideshare service will be especially useful in helping to fill in gaps in public transit in Bronzeville, which like much of the city’s South and West sides, is underserved by public transportation.

BCDP is also adding its input into initiatives like the Chicago Transit Authority Better Streets for Buses plan, which aims to expand clean transportation options and develop safer streets in communities of color.

”If you’re gonna electrify your bus fleet, why would you launch the 20 or 30 new electric buses anywhere other than in a Justice40 community where the air quality is poorest, where the need for a clean energy transportation solution is greatest?” Davis said, referring to the Biden administration program that aimed to ensure that Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities would receive a substantial proportion of allotted federal funds and other resources.

In 2024, BCDP participated in the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Clean Energy to Communities program, which supports community-led projects. BCDP also collaborated with NREL, Argonne National Laboratory, and local universities to launch the EV Institute, according to Davis.

The EV Institute, still under development, has been tasked with empowering the community to implement mobility and transportation equity. For example, there are plans to provide in-person and online education about the benefits of electric vehicles, according to Davis.

This holistic view reflects BCDP’s forward-thinking approach to electrifying transportation, said Julia Hage, manager of the transportation team at the Center for Neighborhood Technology in Chicago, which works with BCDP on its clean energy and community development initiatives.

Like many environmental justice community organizations, BCDP is taking the lead on its own initiatives around economic development, resiliency, and climate mitigation, Hage said.

While welcoming technical assistance and financial resources from outside organizations, environmental justice–based community organizations are nonetheless taking a more assertive approach toward self-determination. The Center for Neighborhood Technology has embraced its supporting role in empowering environmental justice communities to take their rightful seats at the clean energy transition table, Hage said.

“Oftentimes with these different progressions of technology and transportation, the communities are left behind because they’re not included in these conversations,” Hage said. “A lot of harm has been done to communities because of top-down planning decisions.”

Beyond collaborating with BCDP on transportation electrification, Hage said her organization is pulling the group into transportation equity work, too.

This approach was evident in a recent “EV 101” information session that the Center for Neighborhood Technology conducted to educate community-based organizations on how to promote electric vehicle adoption, in which BCDP acted as both a participant and a subject-matter expert.

“[BCDP was] able to also provide information to other CBOs, which I thought was a really cool benefit of having a cohort of community-based orgs,” Hage said. “No matter where they were in their journey of electrification or clean transportation, they could share with each other things that they knew from their experience.”

While the Center for Neighborhood Technology and BCDP have multiple sources of funding outside the federal government, the sudden inability to rely on federal funding has made it harder for them to carry out their mission.

“That’s part of our story now, too. We’re going to continue this decarbonization even in the face of all these cutbacks,” Davis said. “We have community engagement programs that are now on hold that we were relying on for this year and the summer. That won’t happen, at least not in a timely manner, but we’re going to do this anyway because we’re using mostly city and state funds.”

The federal government’s abrupt cancellation of promised funds has had a profound impact on the broader environmental justice community that the Center for Neighborhood Technology and BCDP are a part of. In the resulting atmosphere of uncertainty, many of these organizations are questioning any future reliance on the federal government, Hage said.

“The really alarming thing is, we’re seeing these full-on pauses and stop-work orders; resources that have been already allocated are being told to stop,” Hage said. “Some speculate like, ‘Oh, it’s just to confuse us. It’s just to make us scramble. They’ll have to go back on this. There’s no way.’ And there’s other folks who are kind of like, ‘We can’t even trust this money anymore.’ We’re still just kind of on edge, like, ‘Hey, is this going to happen?’”

One potential strategy is to advocate for state and local clean energy regulations and carbon-free transportation initiatives, along with increased emphasis and reliance on state-level organizations, such as the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, Hage said.

“I am sure organizations right now don’t want to find themselves in this situation,” Hage said. “And I’m sure that they will want to redirect their focus on ‘What are grants that won’t be suddenly paused or suddenly taken away from us?’ And that’s why I think the focus on state and local resources is in conversation. Though, a lot of state money comes from the federal government. So, it’s kind of about ‘How do we best utilize this money while we have it?’”

The federal government’s purge of environmental justice data makes it harder to direct resources to where they are most needed. Nonetheless, BCDP and other environmental justice–focused organizations are determined to continue moving forward while acknowledging the significance of the challenges ahead.

“The freezing of federal grants and loans previously appropriated by Congress has been disruptive and is being challenged in court as unlawful overreach. The ultimate impact, therefore, is not yet fully known,” Davis said in an email.

“However, we remain undaunted in our work advancing renewable energy and clean transportation as economic and workforce development opportunities that make our communities healthier, safer, more livable and sustainable.”

A wave of new reports and data out this week showed just how good of a year 2024 was for U.S. clean energy, especially solar and batteries. Here are a few highlights:

2025 could be another big year. The U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts solar will once again lead power plant construction and that energy storage deployment will shatter last year’s record.

But those predictions come with two major caveats: The White House and Congress.

The Trump administration has already taken direct aim at offshore wind construction and at loans that were set to support battery factories and other clean energy projects. Developers fear Congress will roll back Inflation Reduction Act investment and production tax credits, which are a major reason why clean energy deployment and manufacturing surged in the past year.

House Republicans’ budget talks haven’t yet targeted those particular incentives, and 21 GOP Congress members this week called for preserving them. Still, the IRA’s precarious position is making it hard for clean energy developers to plan ahead. As Morningstar analyst Brett Castelli put it to Heatmap, “all businesses like certainty” — and Congress and the Trump administration aren’t providing much of that these days.

Here are two more big stories from this week:

A lot is going on at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency this week. For starters, EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin said he terminated $20 billion in federal “green bank” funds for climate nonprofits, Canary Media’s Jeff St. John reports. A judge seemed skeptical of Zeldin’s allegations of “misconduct, conflicts of interest, and potential fraud” in a Wednesday hearing.

Zeldin also announced Wednesday that he’s targeting dozens of climate and environmental regulations for rollback. Power plant and tailpipe emissions rules are among those on the chopping block, though experts say it could take years — and willing courts — for Zeldin to achieve his deregulatory dreams.

The EPA has also canceled more than 400 grants across “unnecessary programs,” Zeldin said, though he wouldn’t specify further. It all comes on top of plans to shutter the EPA’s environmental justice offices, just days after Zeldin recalled workers in those offices from administrative leave.

Energy industry leaders met this week in Houston for the annual CERAWeek conference, which turned into a celebration of all things fossil fuels. U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright kicked things off with a promise that the Trump administration will “end the Biden administration’s irrational, quasi-religious” climate policies, while fossil fuel executives praised President Donald Trump’s deregulatory push and announced they are stepping back from clean energy promises.

But it wasn’t all love for Trump policies. Some fossil fuel leaders quietly aired their grievances with the president’s trade fights, saying they’re driving up costs even as he tries to boost the industry.

The latest on tariffs: Ontario’s premier lifts a 25% surcharge on Canadian power exported to Michigan, Minnesota, and New York, but President Trump’s tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from the country and beyond still went into effect Wednesday. (CNN)

Climate suits safe for now: The U.S. Supreme Court declines to hear an argument by 19 Republican attorneys general seeking to limit states’ abilities to sue fossil fuel companies for climate damages. (New York Times)

It’s all about timing: Time-of-use electricity rates, which charge customers more during times of high power demand and less when it’s low, could make heat pumps more financially worthwhile in areas where fossil gas is cheaper than electricity. (Canary Media)

Dive deeper: A time-of-use rate pilot program helped Chicago-area utility customers save money, and it will soon let more residents opt in. (Canary Media)

Power plant preparations: Several states are devising tax incentives and loosening regulations to encourage power plant construction and prepare for rising electricity demand stemming from data center expansions. (Associated Press)

Sunshine State: Florida built 3 GW of utility-scale solar last year, second only to Texas, even as the state’s Republican leadership continued to fight climate action. (Canary Media)

Reliving EV history: A Chicago-area environmental justice community is reigniting its 100-year history as an electric vehicle hub by building a charging network it hopes can get more Black and Brown drivers into EVs. (Canary Media)

Smells like clean energy: A startup is adapting fusion technology to blast through rock that would destroy conventional drill bits, letting it get deeper into the Earth to unlock hotter geothermal power — and the result smells like toasted marshmallows. (Canary Media)

One recent day in a warehouse south of downtown Houston, I got a peek at something that just might revolutionize the clean energy transition: a molten orange puddle of instantly liquefied rock.

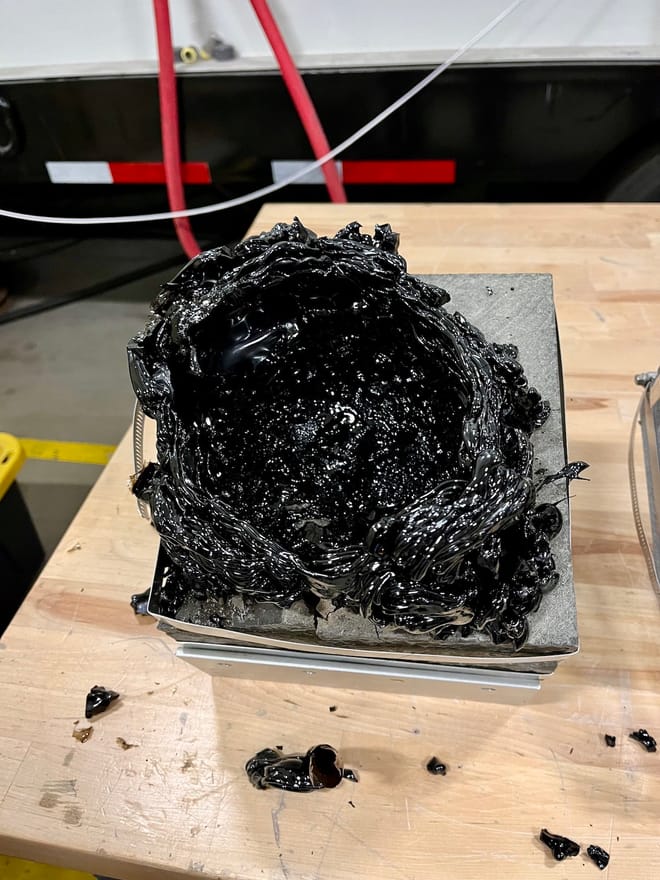

Moments before, an attendant loaded a slug of basalt under a metal-frame structure that looked like something a supervillain might point at a tied-up James Bond, and I was ushered behind a protective barrier. An order went out, the contraption began to whir, and we turned our focus to a TV screen, where the solid rock erupted in a blast of white light that overwhelmed the livestream camera.

One mustn’t believe everything that appears on a screen, but then Carlos Araque, CEO and co-founder of advanced geothermal startup Quaise Energy, led us back to the rig, and there was the freshly blasted rock. A minute ago, it hit as much as 2,000 degrees Celsius, but the molten goop had already solidified into a crown of shiny obsidian. Heat radiated from it, warming my hand as I hovered it a few inches away. The air smelled like toasted marshmallows, if the marshmallows were made of stone.

The flashy demonstration was just one example of how startups are looking to revolutionize geothermal energy production. The U.S. built its biggest geothermal power-plant complex in 1960, but construction has stagnated for decades. Geothermal serves a mere 0.4% of U.S. electricity generation; its nearly 4 gigawatts of capacity amounts to roughly the solar and battery capacity Texas installs in four months these days.

The way out of this decades-long malaise may simply be down. The more subterranean heat a geothermal plant can access, the more energy it can generate, and the Earth gets hotter closer to the core. But the intense conditions below a few miles deep rapidly wreck conventional drill bits.

Araque figured that if he could build a strong enough drill bit, it could harness this super-deep heat and deliver cheap, clean, and abundant geothermal power, pretty much anywhere.

So he left a career in oilfield drilling and formed Quaise in 2018 to do exactly that. Or, more precisely, the company adapted the gyrotron, a tool honed by the nuclear fusion industry that emits millimeter waves, which fall on the electromagnetic spectrum between microwaves and infrared waves. Fusion researchers use them to heat plasma to unfathomably high temperatures. But these waves exert a dramatic effect on rock, so Quaise leadership repurposed them to bore through depths that would demolish conventional drill bits, and perhaps unlock a new golden age of geothermal.

Araque likened the technology to the familiar microwave oven, which heats food by zapping it with a particular band of electromagnetic waves that excites water molecules.

“Translate that into rock,” he said. “Well, rocks love millimeter waves. You put millimeter waves into rock, they soak it up, they light up instantly.”

He first pitched me on his super-powered drill bit six years ago. At the time, it all sounded like science fiction, something that Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers might study and venture capitalists might take a flyer on but that wouldn’t materialize as real technology.

In fact, Quaise did spin out of an MIT lab, and it did raise venture capital for the idea — more than $100 million to date from Prelude Ventures, Mitsubishi, and others. Seven years into the project, however, here I was, smelling the deep, toasty scent of freshly bruleed rock. Deep geothermal energy suddenly seemed a little less like sci-fi and a little more plausible.

Still, Quaise has plenty more work to do before it can deliver its transformative promise — and that starts with getting out of the lab and into the field.

By the time I visited in late January, Quaise had been melting rock outside of the lab but on its own property for weeks. I personally witnessed rock-melting in two places: in the hangar, with a drill rig pointing the millimeter-wave beam at a target rock, and in the yard, where a contraption mounted on tank treads blasted into a rock sample placed in a concrete receptacle on the ground.

“This is the first demonstration of capability, outside, at full scale,” Araque said of the installation.

These tests are necessary to calibrate the novel combination of millimeter-wave emitter and conventional oil-drilling rig. (The Quaise founders know their way around that world, having come from drilling powerhouse Schlumberger.) Quaise proved it can transmit the waves while moving the device, something that the nuclear fusion folks never needed to test. The company’s “articulated wave guide” also showed it can achieve a consistent round shape for its borehole, at least over short distances.

The tests so far amount to the karate demonstration where someone chops through a stack of two-by-fours: Most impressive but not a commercially viable way to chop wood. The next step is obvious — Quaise needs to get out and drill into the earth. That’s coming soon.

Quaise obtained a test site in north Houston where it can drill up to 100 feet underground. The 100-kilowatt gyrotron system I saw firing up in the warehouse has already been moved to this field site, where Quaise is connecting it to a full-scale drilling rig owned by partner Nabors Industries; its mast will soar over 182 feet tall. Drilling should begin in April, cutting into an existing well stuffed with rock samples — outdoors but still a controlled environment.

Soon after, Quaise will swap that out for a new 1-megawatt system, delivering 10 times the power to speed up subsurface boring and maintain an 8-inch-diameter hole, bigger than the initial test holes. That device will use a comparable amount of power as is used by conventional drilling rigs, Araque noted.

Drilling 100 feet down is a start but far from sufficient. The company also secured a quarry site near Austin that provides the opportunity to drill nearly 500 feet through pure granite. Once the technology graduates to drilling thousands of feet, Quaise plans to piggyback on the existing drilling industry with its “BYOG” approach.

“Bring a gyrotron, bring the waveguide, bring the power supply, plug it into the drilling rig,” Araque said. “There’s thousands of drilling rigs in the world. You just go and plug and play into them.”

If and when the time comes to drill for actual power plants, Quaise aims to ride conventional drilling technologies as far as they’ll go. The plan is to hire traditional rigs to burrow through the first 2 to 3 kilometers of subsurface (up to nearly 2 miles) until the drill hits what’s known as basement rock.

After hitting basement rock, Quaise will swap drill bits for its millimeter-wave drill and blast to about 5 miles deep in favorable locations — even that far down, some places have easier access to heat than others. Operators will pump nitrogen gas into the hole to flush out the dust from vaporized rock as the drill moves ever deeper.

Quaise leaders did not disclose a timeline for the company’s first commercial deep drilling. At that point, Quaise will need to build an actual power plant and navigate the myriad permitting and transmission-connection hurdles that face renewables developers broadly. The company is running this development process in-house and already has multiple geothermal leases secured, a spokesperson noted.

In the meantime, a handful of other startups are making headway on commercial-scale geothermal plants, albeit with different approaches.

Fervo Energy has applied fracking technologies to geothermal drilling to make the process more efficient; after a successful 3.5-megawatt trial project in Nevada, the company began drilling the 400-megawatt Cape Station plant in Utah.

Closer in principle to Quaise, a Canadian startup called Eavor is developing ways to drill deeper than was economically practical before. Instead of reinventing the drill itself, Eavor defends it with insulation and “shock cooling” to avoid crumbling in deep, high-temperature rock.

“Most oil and gas directional drilling tools are rated for 180C temperatures, [but Eavor’s] insulated drilling pipe has a cooling effect on the tools making them work at even higher temperatures just by insulating the pipe,” a company spokesperson said in an email.

Eavor notched a big win in 2023, when it drilled a test well in New Mexico to depths of 3.4 miles and through rock as hot as 250 degrees Celsius. Now it’s drilling a closed-loop project in Germany to generate 8.2 megawatts of electricity and 64 megawatts of heating.

Taken together, geothermal innovators like Quaise, along with the somewhat less science-fictiony enhanced geothermal startups like Fervo and Eavor, could produce the “clean firm” power that energy modelers say is necessary to balance out cheap wind and solar in the quest to decarbonize the electrical grid.

“Advanced geothermal technologies could unlock a terawatt-scale resource that can deliver clean energy on demand,” said Jesse Jenkins, an authority on net-zero modeling and assistant professor at Princeton University. “That would be an enormously valuable tool to have in our toolbox.”

Quaise could in theory supply those other geothermal innovators with a better type of drill to extend their range. But Araque insisted Quaise wants to be in the power generation business, not the widget business.

The company also has to manage an evident chokepoint in its development: those highly specialized gyrotrons. Quaise owns four, Araque said; the global gyrotron supply chain currently can’t handle an order for 10 more. That’s not an issue while Quaise works its way up to deep subsurface drilling, but the growth trajectory of the gyrotron suppliers could limit how much power-plant drilling the company can perform simultaneously in the future.

The work to extend from boring a few inches of rock to miles of it should not be underestimated, but Quaise has already crossed the more daunting chasm from never melting rock with an energy beam to doing so daily.

Everyone agrees that California’s major utilities are charging too much for electricity. But as in previous years, state lawmakers, regulators, and consumer advocates are at odds over what to do about it.

With the state’s three biggest utilities reporting record profits even as customers’ rates have skyrocketed, critics say the time is right to pass laws that will force regulators to more tightly control key utility costs — or even outright curb utility spending and profits.

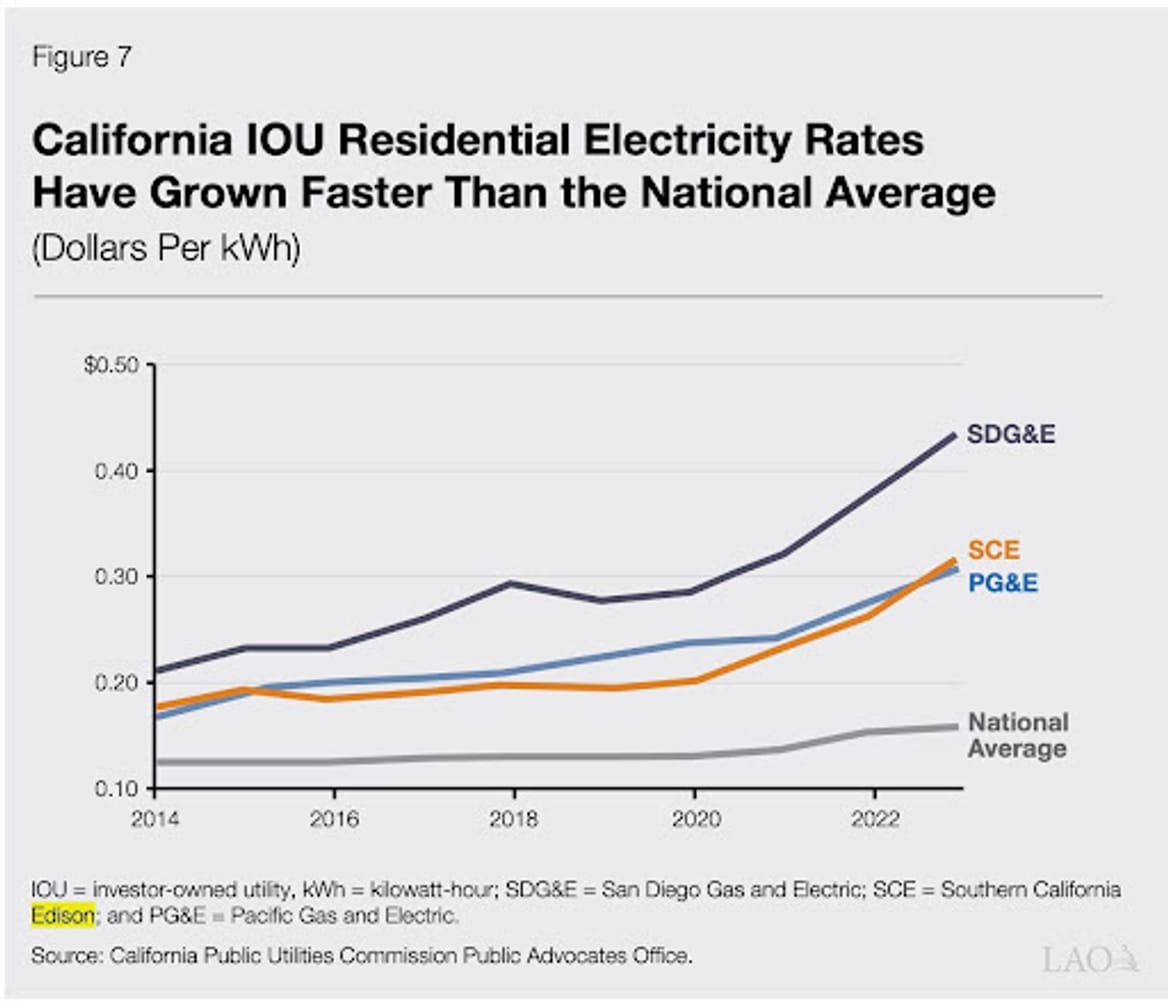

Customers of Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric now pay roughly twice the national average for their power, with average residential rates rising 47% from 2019 to 2023, according to a January report from the state Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Rates are set to climb even further in the coming years as utilities look to expand their power grids to meet growing demand from data centers, electric vehicle charging depots, and millions of households buying EVs and heat pumps. Utilities also need to build high-voltage transmission lines to connect far-off clean energy resources to population centers. And they need to harden and protect thousands of miles of low-voltage power lines to prevent deadly wildfires in a landscape that’s growing more susceptible to conflagration because of climate change.

Utilities are allowed to earn a profit on these infrastructure investments and to pass the costs onto customers — but only within reason. It’s the job of regulators to ensure that profits aren’t disproportionate to what utilities charge ratepayers.

Consumer advocates are now demanding that the California Public Utilities Commission be more aggressive in challenging PG&E, SCE, and SDG&E’s spending plans, which have allowed them to earn more profits than ever over the past year. In October, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) ordered the CPUC to issue a report on how to curb rate increases.

“There’s agreement that record-breaking shareholder earnings make no sense along with skyrocketing costs,” said Mark Toney, executive director of The Utility Reform Network (TURN), a ratepayer advocacy group, and that “utilities need to be held more accountable for their spending.”

TURN is supporting a list of bills being introduced in this year’s legislative session that take aim at utility costs. Some would increase state regulator oversight on utility grid spending. Others seek to forbid utilities from spending ratepayer funds on lobbying and advertising and strengthen CPUC oversight of potential “double recovery,” or utilities collecting funds for projects already financed via other means.

Beyond TURN’s list of favored bills, there are more aggressive legislative proposals that would limit utility rate increases to no higher than the general rate of inflation and force utility shareholders to pay more into a state fund created to shelter utilities from bankruptcy as a result of having to pay for catastrophic wildfires caused by their equipment. PG&E was forced into bankruptcy in 2019 under these conditions after a failure of one of its power lines sparked the state’s deadliest-ever wildfire in 2018.

Legislation that would order the CPUC to increase oversight of utility spending or limit the costs utilities can pass on to customers faces an uphill battle. Last year, a number of reform proposals faltered in the face of heavy lobbying from utility workers unions and pushback from utilities, which spend generously on state political campaigns.

But with customers of California’s three big utilities now paying the highest rates in the nation outside Hawaii and one in five California households struggling to pay their monthly bills, the public pressure to do something may outweigh utility lobbying muscle, advocates say.

Last month, the California state Senate Energy, Utilities and Communications Committee held a legislative hearing where the CPUC briefed lawmakers on its new report on how to contain rate increases.

That report shied away from suggesting major clawbacks in utility spending or limiting profits. Instead, it focused on shifting some costs now passed through to ratepayers — including payments to customers who have rooftop solar, wildfire mitigation and recovery investments, and programs that boost energy efficiency and help low-income customers pay their bills — to “other sources of funding.” That could include state taxpayers, California’s cap-and-trade program, or customers of publicly owned utilities.

All of these proposals would require legislative action, and some lawmakers pushed back on the idea that utilities should be able to shift costs that are their responsibility under law. But CPUC President Alice Reynolds said the alternative — forcing utility shareholders rather than ratepayers to bear more costs — could violate legal precedents that allow utilities a “reasonable rate of return to attract investment in the system,” as she put it.

State Sen. Josh Becker (D), chair of the committee, said during the hearing that legislative leaders and Gov. Newsom’s office plan to put together a bill focused on energy affordability in the coming months.

Toney said he’s hopeful this affordability package “has some of the proposals that went down at the last minute last year, and that there’s going to be a lot more support for them” this year. But he was also critical of the CPUC’s report. “I’ll tell you what was missing” from it, he said — “any conversations about utility profits.”

PG&E, the state’s biggest utility, has reported record-breaking profits over the past two years. The average customer bill increased more than 35% between 2021 and 2023, and CPUC approved six PG&E rate hikes in 2024. The utility’s rates will increase again this year to cover the cost of keeping the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant open.

SCE, the state’s largest electric-only utility, reported record-setting profits in 2024, after winning CPUC approval for rate hikes last year. Another rate hike was approved in January.

SDG&E reported profits near its all-time high last year after record-high profits in 2023 and 2022. The utility’s rates have increased to become among the highest in the nation, as shown in this chart from the state Legislative Analyst’s Office.

The CPUC’s report stated that “the biggest drivers of rate increases” are “the growth in spending to address wildfire mitigation” as well as “the cost shift that results from legacy Net Energy Metering programs,” which compensate customers with rooftop solar systems for electricity they send back to the grid. The CPUC delegated to secondary status the costs of “energy transition related investments in transmission and distribution infrastructure.”

But rooftop solar incentives don’t deserve most of the blame for rising rates, said Loretta Lynch, an attorney and energy policy expert who served as CPUC president from 2000 to 2002. She is also a longtime critic of the current CPUC commissioners appointed by Gov. Newsom.

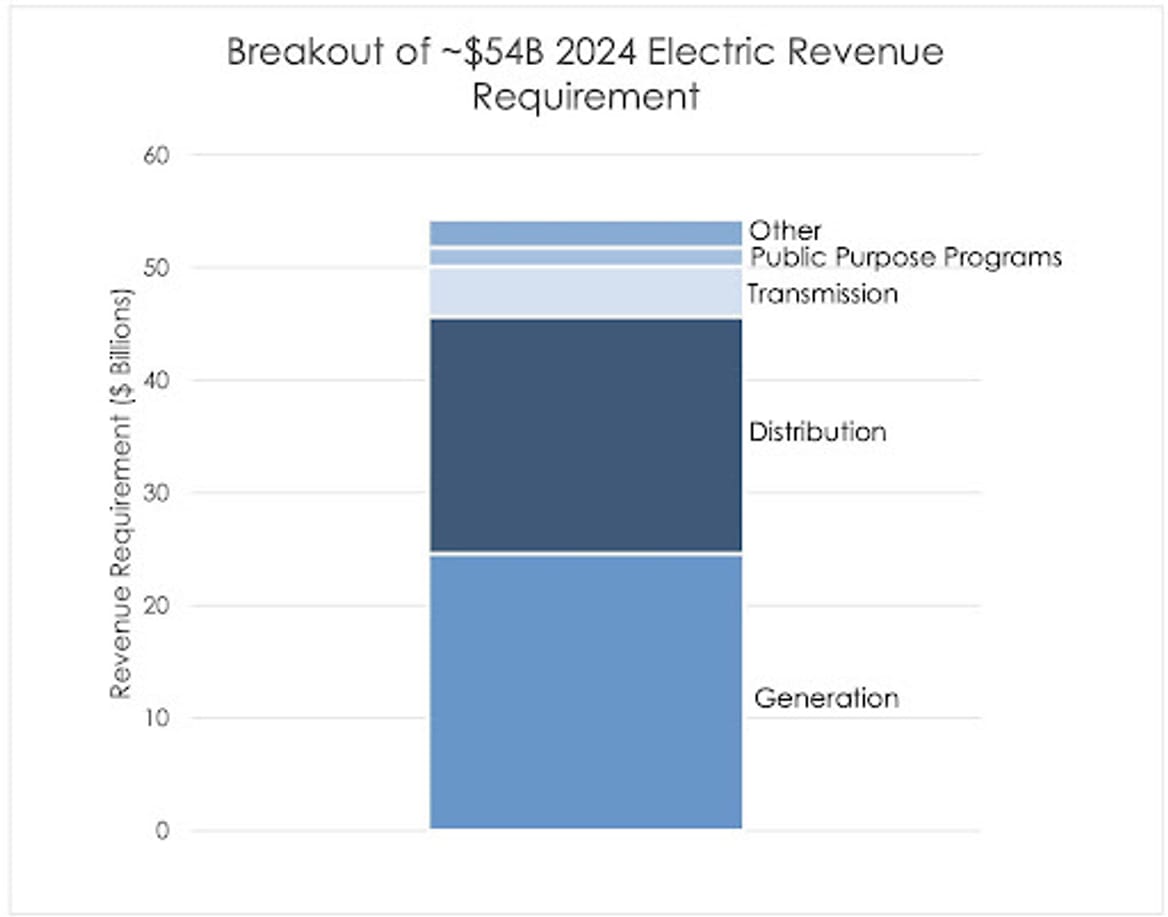

Instead, she said during a February webinar presenting new data on the connection between utility spending and rising rates, “the primary drivers of a vast majority of the costs over the last five to 10 years have been extraordinary procurement” of clean energy at the early stages of the state’s energy transition, when solar power was far more expensive than today, and, more notably, “the tripling of the costs of transmission and distribution” grid investments over the past decade.

Other energy analysts, including some who strongly disagree with Lynch’s views on rooftop solar, share this perspective on the grid’s role in driving up utility costs.

Severin Borenstein, head of the Energy Institute at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, is a major backer of the proposition that rooftop solar is causing bills to rise for other customers. He reiterated that position in a February presentation to the Little Hoover Commission, an independent state oversight agency, noting the significant costs of “public purpose programs,” such as the billions of dollars that utility customers at large pay to support rooftop solar incentives and low-income ratepayer assistance.

But Borenstein also said a majority of the rising utility costs over the past decade are tied to investments in low-voltage distribution grids and wildfire hardening and prevention.

“Those last two sort of meld together because we’re spending a whole lot of money on upgrading our distribution network, reinforcing our distribution network, in some cases, under-grounding it, in order to reduce wildfires,” he said.

The below chart from the CPUC’s February report highlights the majority of costs that come from paying for electricity generation and maintaining the utilities’ sprawling low-voltage distribution grids.

Borenstein agrees with the CPUC that rooftop solar incentives make up a significant portion of rising utility rates — a view that’s disputed by solar and environmental advocates. But even when the costs of net metering are calculated in the way that the CPUC proposes, they still make up a relatively small portion of typical residential utility customer bills compared to the “other” category that includes generation and grid costs, as the below chart from the Legislative Analyst’s Office report shows.

The Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the few environmental organizations that strongly favors reducing rooftop solar compensation, issued a report this week proposing a host of ways to reduce PG&E’s rates, including shifting those costs away from ratepayers. But NRDC also found that the “largest contributor to PG&E’s skyrocketing rates is the cost of vegetation management and hardening the grid to prevent wildfires,” making up more than half of the utility’s rate increases above the rate of inflation since 2018.

Going after those costs is tricky, however. When it comes to generation, utilities can’t back out of contracts for expensive power, even if they were signed more than a decade ago. Nor can they avoid buying power on the state’s energy markets during times when those prices spike.

Tackling grid costs puts regulators and lawmakers in a bind as well. Nobody wants utilities to skimp on critical investments like replacing aging equipment or protecting power lines from being knocked down by trees or high winds. Efforts to police utility grid investments risk forcing regulators and utilities to spend lots of time and effort delving into the minutiae of those plans without any clear promise of savings to show at the end of it.

Even so, Toney highlighted several bills being proposed this year, and others he hopes will be revived from last year’s session, that could drive down some of these costs.

On wildfire-related expenditures, he’d like to see a new bill that revives the policies proposed by SB 1003, a bill that failed to pass last year. The bill would have instructed the CPUC to limit utility wildfire spending outside of closely examined plans and put utility wildfire planning more squarely under the commission’s control.

Another option to address utility spending is AB 745, a bill that would increase state oversight of utility transmission grid upgrades. Energy analysts argue that a regulatory gap between federal and state authority over certain types of smaller grid projects has led to utility overspending on those projects. AB 745 cites a CPUC report that found $4.4 billion in transmission investments by California’s big utilities between 2020 and 2022, or nearly two-thirds of total grid spending, fell into this category.

California could also find other ways to pay for grid investments, Toney said. Those options can include securitization — having a utility issue bonds backed by the steady stream of payments its customers make on their bills — or the state issuing bonds to pay for certain utility costs. Both replace a portion of costs that are passed on to ratepayers, which “saves money because there’s no shareholder profit to be made,” he said.

SB 330, a bill proposed by state Sen. Steve Padilla (D), would authorize the state to “pilot projects to develop, finance, and operate electrical transmission infrastructure” via “low-cost public debt and alternative institutional models.” California will need to spend an estimated $45.8 billion to $63.2 billion on transmission by 2045, and an October report from the nonprofit Clean Air Task Force found that such public financing options could annually shave billions of dollars from rate increases in future years.

Some consumer advocates say lawmakers and regulators need to go after rising rates directly by limiting the return on investment that utilities are permitted to pass on to customers. Utility critics say that’s the most direct way to halt rate increases.

It’s also the most likely to trigger major pushback from utilities.

“We need to reduce the utilities’ profits to the national average or perhaps tie those profits to increases in safety,” Lynch proposed during February’s webinar. “As long as our policymakers focus on the wrong problem, we won’t find the right solution to reducing customers’ punishing and unwarranted bills.”

These efforts are hampered by the complexity and volume of data that goes into calculating such returns on investment as well as the fact that utilities control all the data. Indeed, utility critics have noted that recent rate-increase requests from PG&E have been approved by the CPUC in a perfunctory manner, with little to no attempt to order the utility to prove its cost increases were warranted.

Lynch blamed CPUC commissioners. ”It’s a fundamental failure of regulation, but it’s also a fundamental failure of political will to require the regulators to do their job as written in the law,” she said.

Utility finance expert Mark Ellis agreed that the CPUC needs to cut utilities’ profits. As an independent consultant and senior fellow at the American Economic Liberties Project, Ellis published a January paper accusing utilities of using financial legerdemain to justify excessive returns on their investments — and regulators of violating their duty to hold utilities to account.

The regulatory compact between states and investor-owned utilities boils down to this, he told Canary Media: “We’re going to give you a monopoly, but we won’t let you charge monopoly rents. Anything above your cost of capital is a monopoly rent.”

In an opinion piece in the San Francisco Chronicle, Ellis argued that California’s investor-owned utilities have been earning far above the cost of capital for decades — an assertion he backs up from experience working as former chief of corporate strategy and chief economist at Sempra, the holding company of Southern California Gas Co. and SDG&E.

The Energy Institute’s Borenstein agreed during his February presentation that utilities have “some important perverse incentives for capital investment” and that “cost of equity is the big point of contention because it’s hard to know what you need to pay stock shareholders to get them to invest.”

At the same time, “I don’t blame the CPUC for this,” he said. “I think the CPUC is massively understaffed and undercompensated, and they are just overwhelmed with the many things that they are required to do with limited staff. And when they get into these rate-of-return hearings, the utilities are able to bring world experts in finance.”

Ultimately, he said, “the CPUC is really outgunned and outmanned.”

Some lawmakers are going after utility profits more directly. SB 332, a bill sponsored by state Sen. Aisha Wahab (D), would cap investor-owned utility rate increases for residential customers to no more than the Consumer Price Index, a federal measure of cost-of-living inflation. It would also make shareholders rather than ratepayers provide more of the funding for the state’s utility wildfire fund — a sensitive issue amid rising investor uncertainty regarding SCE’s potential liability for January’s devastating Eaton Fire. SB 332 would also tie utility executive compensation to safety metrics.

“This bill flips the script and puts utility profits on the table,” said Roger Lin, a senior attorney at the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity, which supports the legislation. While he conceded the proposal will face serious pushback from utilities, “we have to start looking at the systemic causes of the affordability crisis we have today in California.”

As Illinois looks to prepare its electric grid for the future, a new voluntary program in the Chicago area promises to lower costs for both customers and the utility system as a whole.

ComEd is finalizing plans to roll out time-of-use rates in 2026 following a four-year pilot program in which participants saved money and reduced peak demand between 6.5% and 9.7% each summer.

Under a plan before state utility regulators, customers who sign up would pay a much steeper energy-delivery charge during afternoon and early evening hours but see a significant discount overnight. The goal is to shift use to hours when the grid tends to be less congested as well as deliver cleaner and cheaper power.

“What we saw from the pilot was people did change their habits,” said Eric DeBellis, general counsel for the Citizens Utility Board, the state’s main utility watchdog.

Most standard customers are set to pay an energy-delivery charge of 5.9 cents per kilowatt-hour next year, while customers who enroll under ComEd’s proposed time-of-use program would pay a “super peak” delivery rate of 10.7 cents per kilowatt-hour between 1 p.m. and 7 p.m. but just 3 cents during overnight hours.

“The key to savings will be customers limiting usage from 1 pm to 7 pm,” John Leick, ComEd’s senior manager of retail rates, said in an email.

Under the proposal, most time-of-use rate customers would pay delivery rates of around 4 cents per kilowatt-hour during the morning, from 6 a.m. to 1 p.m., and in the evening between 7 p.m. and 9 p.m.

The details were approved in January by the Illinois Commerce Commission but put on hold last Thursday after commissioners agreed to consider a request by ComEd to also incorporate energy-supply charges into the program. (The initial proposal included only the portion of customers’ bills that pays for the delivery of energy but not the cost of electricity itself.)

The Citizens Utility Board is happy with the plan approved in January, DeBellis said, and it wants to ensure a delivery-only option remains for customers who buy power from alternative retail electric suppliers since these customers would not be able to participate in a supply-charge ComEd program. The utility watchdog also would have liked the “super peak” hours to be a bit shorter.

“For your typical upper-Midwest household, about half of their electricity is HVAC, and in the summer bills go up because of air conditioning,” DeBellis explained. “We were worried about the hours of super peak, the length of time we’re asking people to let the temperature drift up.”

The prospect of limiting air conditioning on hot afternoons could dissuade people from enrolling in the program, DeBellis continued. “Since each person’s subtle behavior changes are going to be small, it needs to be really popular to have an impact,” he said.

Consumer advocates have long asked for time-of-use rates, which are considered crucial as Illinois moves toward its goal of 1 million electric vehicles by 2030. If too many EVs charge during high energy-demand times, the grid could be in trouble.

“We want EVs to be good for the grid, not bad,” said DeBellis.

People with electric vehicles will save an extra $2 on their monthly energy bill per vehicle just by enrolling in the proposed ComEd time-of-use program, with a cap of two vehicles for up to two years.

“This will help incentivize customers with EV’s to sign up and pay attention to the rate design and hopefully charge in the overnight or lower priced periods,” said Leick.

Richard McCann, a consultant who testified before regulators on behalf of the Citizens Utility Board and the Environmental Defense Fund, recommended that in order to qualify for rebates for level 2 chargers, customers must participate in the new time-of-use program or other programs related to when electricity is used.

DeBellis and his wife recently bought an EV, and he thinks time-of-use prices could be an extra incentive for others to follow suit. However, he thinks dealers and buyers are more focused on EVs “being cool” and tax incentives toward the lease or purchase price, rather than fuel savings.

“I don’t have the impression people trying to buy a car are doing the math and thinking about how much they would save on fuel” with an EV, he said. “Time-variant pricing makes those savings even more, but the math is kind of impenetrable for most people. In my humble opinion, fuel savings should be a way bigger factor, and time-of-use rates should be part of it.”

ComEd crafted the time-of-use program after a four-year pilot and a public comment process overseen by state regulators. The pilot was focused on the energy supply part of the bill, but DeBellis noted that the lessons apply to any time-of-use program, since demand peaks are the same regardless of which part of the bill one looks at.

The pilot program’s final annual report showed that both EV owners and people who did not own EVs significantly reduced energy use during “super peak” hours in the summer. Even though participants without EVs did little load-shifting during the non-summer seasons, they still saved an average of $6 per month during the last eight months of the pilot because of the way electricity was priced in the program. EV owners saved significantly more, with most cutting bills by $10 to $30 per month and some saving over $70 per month from October 2023 to May 2024.

Overall, in the pilot’s final year, energy usage did shift significantly from peak hours to night-time hours thanks to an increasing number of EV owners participating in the program.

In 2021 and 2022, participants in the pilot faced high peak-time energy rates because of market fluctuations. Some customers dropped out for this reason, Leick said, but participation remained near the cap of 1,900 residents during the pilot, with over a quarter of them being EV owners by the end.

Many utilities around the country already offer time-of-use programs: 42% of 829 utilities responding to a federal survey have such rates, according to McCann’s testimony.

ComEd’s filings with state regulators include a survey of 15 time-of-use rates established by seven other large utilities nationwide. The study found that in the first year of ComEd’s pilot program, the utility had a larger proportional difference between peak and off-peak pricing than most of the rates studied. (ComEd’s peak and off-peak rates, however, were lower than most of the others, so the total price difference was larger for other utilities.)

ComEd also saw larger reduction in summer peak-time electricity demand than many of the other time-of-use rates. ComEd’s program structure was similar to that of the other utilities, the company doing the study found, though in California, peak times were later in the afternoon, likely because of the state’s climate and proliferation of solar energy.

The program is designed to be revenue-neutral, meaning ComEd won’t earn more or less depending on when people use energy. Still, it has potential to lower costs to the system overall by helping to make more efficient use of existing infrastructure and postponing the need for new generation or transmission investments.

The new time-of-use rate would only apply only to residents. Industrial and commercial customers already have an incentive to use power at night, since their energy-delivery charge is based on their highest 30-minute spike between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. on weekdays. If a business’ most intense energy use is after 6 p.m. or on weekends, their bill will be lower than if that same spike happened during usual business hours, Leick explained. Commercial and industrial customers’ energy-supply rates, meanwhile, are based on hourly market prices, which are typically higher during peak times.

ComEd has since 2007 offered a voluntary real-time pricing program that lets people save money if they use energy when system demand and hence market prices are lower. But keeping tabs on the market is beyond what most customers other than “energy wonks” are willing to do, DeBellis noted. Only about 1% of residential customers have enrolled in the real-time pricing program since it started, according to McCann’s testimony.

“Real-time pricing was so complicated it was basically gambling,” DeBellis said. “We’re very happy to have a time-based rate offering that’s very predictable, where people can be rewarded for establishing good habits.”

Some clean-energy groups had argued for a program that automatically enrolls residents unless they opted out. DeBellis said the Citizens Utility Board promoted the opt-in version that is currently proposed.

“We want people on this program to be aware they’re on the program, otherwise you won’t get behavior change. You’re just throwing money at random variation,” DeBellis said.

The Clean and Reliable Grid Affordability Act, introduced into the state legislature in February and backed by a coalition of advocacy groups, would mandate large utilities offer residential time-of-use rates, outlining a structure similar to what ComEd is planning. After the rates have been in place for a year, the Illinois Commerce Commission could do a study to see if the rates are indeed reducing fossil-fuel use and work with utilities to adjust if needed.

While the commission’s ruling last week reopens debate about the program’s structure, a ComEd spokesperson said the company is confident it will be available by next year.

For most U.S. homes, heat pumps are a no-brainer: They can lower energy bills and eventually pay for themselves all while slashing carbon emissions. But the economics don’t work in favor of heat pumps for every home — and particularly not for those in states that have high electricity prices relative to those of fossil gas.

Adjusting the structure of customer electricity rates could turn the tables, according to a report out today from the nonprofit American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, or ACEEE.

The ratio of average electricity prices to gas prices (both measured in dollars per kilowatt-hour) is known as the “spark gap” — and it’s one of the biggest hurdles to nationwide electrification. A heat pump that is two to three times as efficient as a gas furnace can cancel out a spark gap of two to three, ensuring energy bills don’t rise with the switch to electric heat. But in some states, the gulf is so big that heat pumps can’t close it under the existing rate structures.

Worse, heat pump performance can decrease significantly when it’s extremely cold (like below 5 degrees Fahrenheit), so without incentives, the economic case is harder in states with both harsh winters and electricity that’s much more expensive than gas, like Connecticut and Minnesota. In these places, heat pump adoption is “hit by double whammy,” said Matt Malinowski, ACEEE buildings director.

The weather might be hard to change, but the spark gap is malleable: Utilities, regulators, and policymakers can shape electricity rates. By modeling rates for four large utilities in different cold-climate states, ACEEE found that particular structures can keep energy bills from rising for residents who switch to heat pumps, without causing others’ bills to go up.

Flat electricity rates are a common practice. They’re also the worst structure for heat pumps, Malinowski said.

When utilities charge the same per-kilowatt-hour rates at all hours of the day, they ignore the fact that it costs more to produce and deliver electricity during certain hours. That’s because, like a water pipe, the power grid needs to be sized for the maximum flow of electrons — even if that peak is brief. Meeting it requires the construction and operation of expensive grid infrastructure.

Flat rates spread the cost of these peaks evenly across the day rather than charging customers more during the high-demand hours that cause a disproportionate amount of grid costs.

But heat pumps aren’t typically driving peak demand — at least, not for now while their numbers are low. Demand usually maxes out in the afternoon to evening, when people arrive home from work, cook, do laundry, and watch TV. Households with heat pumps actually use more of their electricity during off-peak hours, like just before dawn when it’s coldest, than customers with gas, oil, or propane heaters.

Heat pumps “provide the utility a lot of revenue, and they do that at a time when there isn’t that much electricity consumption,” Malinowski said.

Under a flat-rate design, cold-climate heat pump owners “are basically overpaying,” he added. “Adjusting the rates to better reflect their load on the system — and the benefits to the system that they provide — is only fair.”

A rate design that bases charges on when electricity is used would help course-correct. Known as “time-of-use,” this structure charges more for power consumed during periods of peak demand and less for power consumed at other times, or “off-peak,” coinciding with heat pumps’ prime time.

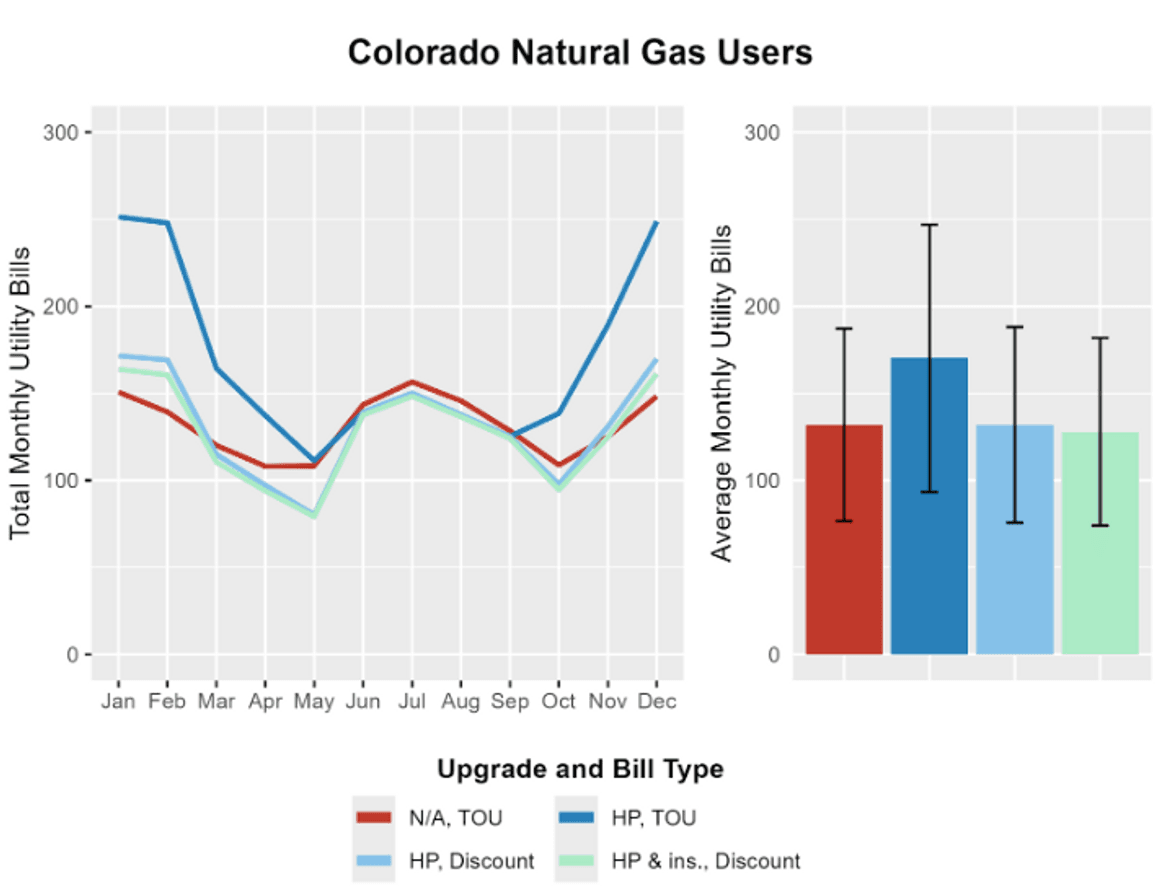

Utility ComEd serving the Chicago area is working to finalize time-of-use rates for households, joining the ranks of several other U.S. providers that already offer this structure, like Xcel Energy in Colorado, Pacific Gas and Electric in California, and Eversource in Connecticut.

Demand-based rates are another way of accounting for a customer’s peak demand profile and can help reduce a heat pump owner’s energy bills. This approach tacks on fees scaled to a customer’s peak demand that month. If it’s 3 kilowatts, and the demand charge is $10 per kilowatt, the fee will be $30. But importantly, this structure also lowers the rates charged for the total volume of electricity.

Even though households switching from gas to heat pumps under such a program would see higher charges for peak demand than before, Malinowski said “they’ll be using so much more electricity overall that they end up benefiting much more from that lower volumetric [per-kilowatt-hour] charge.” As a result, their energy bills can be lower than with a flat-rate program, the report finds.

Winter discounts also help heat pumps make financial sense. In most states, electricity usage waxes in the summer — when people blast their air conditioners — and wanes in the winter, when many residents switch to fossil-fuel heating.

Some utilities offer reduced electricity prices in winter to drum up business, a structure that benefits households who heat their homes with electrons. Xcel in Minnesota drops its June-through-September summer rate of 13 cents per kilowatt-hour to 11 cents per kilowatt-hour during the rest of the year for all customers. For those with electric space heating, including heat pumps, the rate is lower still: 8 cents per kilowatt-hour — a discount of 39% from the summer rate.

According to ACEEE’s modeling, the winter discount alone can save Minnesota Xcel customers in single-family homes on average more than $350 annually once they swap a gas furnace for a heat pump. Combining the winter discount with existing time-of-use rates or simulated demand-charge rates (given in the study) can further reduce annual bills by another $70.

In Colorado, another state ACEEE analyzed, Xcel provides both time-of-use rates and a much shallower winter discount of about 10%. Even taken together these structures aren’t enough to close the spark gap for heat pumps. Pairing that discount with demand-based rates wouldn’t do the trick either, the team found. Only when they used the much steeper discount that Xcel deploys in Minnesota were they able to keep customers’ modeled heating bills from climbing when they switched to heat pumps.

One more option for utilities and regulators: discounts specifically for customers with heat pumps. More than 80 utilities in the U.S. currently offer discounted electric heating rates, with 12 providing them specifically for households with heat pumps, according to a February roundup by climate think tank RMI.

Massachusetts regulators approved a plan by utility Unitil last June to offer a wintertime heat-pump discount — the first in the state — and directed National Grid to develop one, too. Unitil’s discount amounts to at least 20% off the regular per-kilowatt-hour rate, depending on the plan customers choose. Colorado policymakers are also requiring investor-owned utilities to propose heat pump rates by August 2027.

The takeaway from ACEEE’s results is that in some states, the above rate designs could be promising avenues to ensure switching to heat pumps doesn’t raise energy bills for most single-family households.

But in other cases, additional policy might be needed. Connecticut’s electricity prices are so high that these rate structures weren’t enough to close the spark gap, the authors found. They recommend policymakers consider broader changes like putting a price on carbon emissions, implementing clean-heat standards that require utilities to take steps toward decarbonized heating, or investing in grid maintenance and upgrades to make electricity more affordable — for all customers.

Last May, Florida enacted a law deleting any reference to climate change from most of its state policies, a move Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis described as “restoring sanity in our approach to energy and rejecting the agenda of the radical green zealots.”

That hasn’t stopped the Sunshine State from becoming a national leader in solar power.

In a first, Florida vaulted past California last year in terms of new utility-scale solar capacity plugged into its grid. It built 3 gigawatts of large-scale solar in 2024, making it second only to Texas. And in the residential solar sector, Florida continued its longtime leadership streak. The state has ranked No. 2 behind California for the most rooftop panels installed each year from 2019 through 2024, according to data the energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie shared with Canary Media.

“We do expect Florida to continue as No. 2 in 2025,” said Zoë Gaston, Wood Mackenzie’s principal U.S. distributed solar analyst.

Florida is expected to again be neck and neck with California for this year’s second-place spot in utility-scale solar installations, said Sylvia Leyva Martinez, Wood Mackenzie’s principal utility-scale solar analyst for North America.

Overall, the state receives about 8% of its electricity from solar, according to Solar Energy Industries Association data. The vast majority of its power comes from fossil gas.

The state’s solar surge is the result of weather — both good and bad — and policies at the state and federal level that have made panels cheaper and easier to build, advocates say.

“Obviously in Florida, sunshine is extremely abundant,” said Zachary Colletti, the executive director of the Florida chapter of Conservatives for Clean Energy. “We’ve got plenty of it.”

The state is also facing a growing number of extreme storms. Of the 94 billion-dollar weather disasters that federal data show unfolded in Florida since 1980, 34 occurred in the last five years.

“Floridians have long understood that not only is solar good for your pocket, it’s also good for your home resilience,” said Yoca Arditi-Rocha, the executive director of The CLEO Institute, a Miami-based nonprofit that advocates for climate action. “In the face of increasing extreme weather events, having access to reliable energy is a big motivator.”

The tax credits available under former President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act have also made buying panels cheaper than ever before, she said.

“A lot of people took advantage of that. I’m one of them,” Arditi-Rocha said. “As soon as I saw that the federal government was going to give me 30% back on my taxes, I decided to make the investment and got myself a solar system that I could pay back in seven years. It was a win-win proposition.”

But solar started growing in Florida long before Democrats passed the IRA in 2022, and that’s thanks to favorable state policies.

Municipalities and counties have little say over power plants, giving the Florida Public Service Commission ultimate control over siting and permitting. Plus, solar plants with a capacity under 75 megawatts are exempt from review and permitting altogether under the Florida Power Plant Siting Act.

The latter policy in particular has made building solar farms easy and inexpensive for the state’s major utilities, said Leyva Martinez. Companies such as NextEra Energy–owned Florida Power & Light, the state’s largest electrical utility, have for years patched together gigawatts of solar with small farms.

“We’re seeing this wave of project installations at gigawatt scales, but if you look at what’s actually being built, it’s a small 74-megawatt [project] here or 74.9-megawatt project there,” she said. “It’s just easier to permit in the state, and developers have realized that they can keep installations at this range and they don’t need to go through the longer process.”

The solar buildout has prompted some backlash in rural parts of the state. A bill Republican state Sen. Keith Truenow filed last month proposes granting some additional local control over siting and permitting solar farms on agricultural land.

“You’re starting to see a lot more complaining about the abundance of solar installations in more rural areas,” Colletti said. The legislation, he said, “would add some hurdles and ultimately add costs” but “wouldn’t necessarily reverse the state’s preemption” of local permitting authorities.

NextEra and Florida Power & Light did not respond to an email requesting comment. Nor did Truenow return a call.

While the bill is currently making its way through the Legislature, DeSantis previously vetoed legislation that threatened Florida’s solar buildout.

In 2022, the governor blocked a utility-backed bill to end the state’s net metering program, which pays homeowners with rooftop solar for sending extra electricity back to the grid during the day.

“The governor did the right thing by vetoing that bill that would have strangled net metering and a lot of the rooftop solar industry in Florida,” Colletti said. “I know Floridians are much better off for it because we are able to offset our costs very well and take more control and ownership over our households.”

A telephone survey conducted by the pollster Mason-Dixon in February 2022 found that among 625 registered Florida voters, 84% supported net metering, including 76% of self-identified Republicans.

“It’s not about left or right,” Arditi-Rocha said. “It’s about making sure we live up to our state’s name. In the Sunshine State, the future can be really sunny and bright if we continue to harness the power of the sun.”

As winter turns to spring, Texas is setting new records with its nation-leading clean energy fleet.

In just the first week of March, the ERCOT power grid that supplies nearly all of Texas set records for most wind production (28,470 megawatts), most solar production (24,818 megawatts), and greatest battery discharge (4,833 megawatts). Only two years ago, the most that batteries had ever injected into the ERCOT grid at once was 766 megawatts. Now the battery fleet is providing nearly as much instantaneous power as Texas nuclear power plants, which contribute around 5,000 megawatts.

“These records, along with the generator interconnection queue, point towards a cleaner and more dynamic future for ERCOT,” said Joshua Rhodes, a research scientist studying the energy system at The University of Texas at Austin.

The famously developer-friendly Lone Star State has struggled to add new gas power plants lately, even after offering up billions of taxpayer dollars for a dedicated loan program to private gas developers. Solar and battery additions since last March average about 1 gigawatt per month, based on ERCOT’s figures, Texas energy analyst Doug Lewin said. In 2024, Texas produced almost twice as much wind and solar electricity as California.

When weather conditions align, the state’s abundant clean-energy resources come alive — and those conditions aligned last week amid sunny, windy, warm weather. On March 2 at 2:40 p.m. CST, renewables collectively met a record 76% of ERCOT demand.

Then, on Wednesday evening, solar production started to dip with the setting sun. More than 23,000 megawatts of thermal power plants were missing in action. Most of those were offline for scheduled repairs, but ERCOT data show that nearly half of all recent outages have been “forced,” meaning unscheduled.

At 6:15 p.m. CST, batteries jumped in and delivered more than 10% of ERCOT’s electricity demand — the first time they’ve ever crossed that threshold in the state.

“Batteries just don’t need the kind of maintenance windows that thermal plants do,” said Lewin, who authors the Texas Energy and Power newsletter. “The fleet of thermal plants is pretty rickety and old at this point, so having the batteries on there, it’s not just a summertime thing or winter morning peak, they can bail us out in the spring, too.”

At some level, the March records show clean energy excelling in the conditions that are most favorable to it. Bright sun and strong winds boosted renewable generation, while temperate weather kept demand lower than it would be on a hot summer or a cold winter day. But those seemingly balmy circumstances could belie a deeper threat to the Texas energy system.

“One thing that I don’t think is talked about nearly enough is the potential for problems in shoulder season,” said Lewin.

If unusually hot weather struck during a spring day with lots of gas and coal power plants offline, ERCOT could struggle to meet demand, even if it was much lower than the blistering summer peaks. In fact, this happened in April 2006, when a surprise heat wave forced rolling outages, Lewin noted. Texas officials don’t talk much about climate change, but that kind of hot weather in the springtime is becoming more common.

Last summer produced ample data on how the surge in solar and battery capacity reduced the threat to the grid from heat waves and lowered energy prices for customers. This spring, batteries and renewables are showing they can also fill in the gaps when traditional plants step back.