Evanston, Illinois, just passed an ordinance requiring the city’s largest buildings to eliminate all fossil fuels and use 100% renewable electricity by 2050.

On March 10, the Chicago suburb joined 14 other state and local governments across the U.S. that have enacted policies to decarbonize existing buildings, which often account for the bulk of a city’s carbon emissions. Evanston’s Healthy Buildings Ordinance marks the first such law — known as a building performance standard — to pass in the U.S. this year and the second to be adopted in the Midwest after St. Louis.

More could be on the way soon. Evanston is part of a wave of small cities that have recently passed building performance standards, including Newton, Massachusetts, in December. Another city outside Boston and two in California are also working on adopting standards this year, according to the Institute for Market Transformation, a nonprofit that helps state and local governments implement building efficiency policies.

Under the Trump administration, local leadership is “the only front on which the climate action battle will be fought,” said Jonathan Nieuwsma, an Evanston city council member and key sponsor of the law.

For cities that want to continue climate progress, regulating large, existing buildings is one of the best avenues available, said Cara Pratt, Evanston’s sustainability and resilience manager. Besides targeting local emissions sources, performance standards spur more proactive maintenance to ensure cities are “providing the healthiest indoor air environment possible for the folks who live and work in these buildings.”

The city of Evanston, home to around 75,000 residents, committed to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 under a 2018 climate action plan. Buildings are key to reaching that target: The city’s 500 largest structures alone account for roughly half of total emissions, and the sector overall accounts for about 80%. While the city has adopted building codes to rein in emissions from new construction, existing buildings aren’t subject to equivalent rules to make sure routine upgrades of systems like heating and cooling happen in line with Evanston’s climate goals.

The new law fills in that gap by requiring the city’s biggest commercial, multifamily, and government buildings to reduce their energy-use intensity, achieve zero on-site fossil fuel combustion, and procure 100% renewable electricity by 2050. But the ordinance itself does little aside from setting up long-term goals. Instead, it creates two groups charged with developing the detailed rules needed to actually implement the law.

One is a technical committee that will develop interim targets covering five-year intervals between 2030 and 2050, along with other regulations like compliance pathways and penalties. The other will serve as a community accountability board to ensure the policy’s design and implementation incorporates equity concerns, including by minimizing costs to low-income residents and tenants and providing support to less-resourced buildings such as schools or affordable housing.

Like other building performance standards across the country, Evanston’s policy will set limits on emissions or energy efficiency without mandating how property owners should reach those targets. Buildings can typically choose from a menu of compliance options, from weatherization and efficiency upgrades to installing heat pumps and other electric alternatives.

Nieuwsma describes Evanston’s law as “an enabling ordinance” that “sets up a process for those very important details to be developed with robust stakeholder input.” Once both committees agree on regulations, they will need to be approved by the City Council. Nieuwsma and other officials expect the city to adopt rules sometime next year.

Evanston’s policy is unusual in baking in a high level of formal input from property owners. Three out of six seats on the technical committee will be nominated directly by local building owners associations, an amendment made after several City Council deliberations. (The rest of the members of both committees will be nominated by the mayor.)

The setup is designed to address property owners’ cost concerns and could help Evanston avoid industry pushback that has stymied similar laws in places like Colorado, which currently faces a lawsuit brought by apartment and hotel trade associations against its policy.

Building performance standards are still relatively novel. The first one in the U.S. was introduced in Washington, D.C., in 2018, followed by New York City’s Local Law 97 in 2019. Four states — Colorado, Maryland, Oregon, and Washington — and 11 local governments, including Evanston, have now adopted the policy. More than 30 other jurisdictions have committed to introducing the standards as part of a national coalition that was led by the White House under the Biden administration and is now spearheaded by the Institute for Market Transformation.

Last year, the Biden administration doled out hundreds of millions of federal dollars under the Inflation Reduction Act to cities and states pursuing building performance standards. Evanston was one of them and received a $10.4 million conditional award from the Department of Energy in early January.

But since Inauguration Day, the Trump administration has attempted to freeze and claw back climate funding to nonprofits and local governments. Pratt said the federal government has not told the city that it will withdraw its grant, but Evanston has also not received word on whether the funding will be finalized.

The city had intended to use the grant to hire additional staff and support energy audits for resource-constrained buildings like public schools, Pratt said. Yet regardless of whether the city receives the money, the work to reduce emissions from large buildings will continue, she said, adding that Evanston committed to adopting a building performance standard a few years ago without the promise of federal funding. “To me, it was always a huge positive addition. But it’s not necessary to do the work.”

Jessica Miller from the Institute for Market Transformation, who served on a committee that helped the city develop its ordinance, pointed out that the country’s first building performance standards were passed during the first Trump administration. “There are many jurisdictions that have passed these types of policies without federal support,” she said.

Another proposed energy-saving program is on the chopping block in Ohio.

Duke Energy Ohio quietly dropped plans late last year to roll out a broad portfolio of programs that would have boosted energy efficiency and encouraged customers to use less electricity during times of peak demand. The plans, which would have saved ratepayers nearly $126 million over three years after deductions for costs, were part of a regulatory filing last April that sought to increase charges on customers’ electric bills.

The move came after settlement talks with other stakeholders, including the state’s consumer advocate, which opposes collecting ratepayer money to provide the programs to people who aren’t in low-income groups.

State regulators are now weighing whether to approve the settlement with a much smaller efficiency program focused on low-income neighborhoods.

The case is the latest chapter in a struggle to restore utility-run programs for energy efficiency after House Bill 6, the 2019 nuclear and coal bailout law that also gutted the state’s renewable energy standards and eliminated requirements for utilities to help customers save energy.

Studies show that utility-run energy-efficiency programs are among the cheapest ways to meet growing electricity needs and cut greenhouse gas emissions. Lower demand means fossil-fuel power plants can run less often. Less wasted energy translates into lower bills for customers who take advantage of efficiency programs. Even customers who don’t directly participate benefit because the programs lower peak demand when power costs the most.

Energy efficiency can also put downward pressure on capacity prices — amounts paid by grid operators to electricity producers to make sure enough generation will be available for future needs. Due to high projected demand compared to available generation, capacity prices for most of the PJM region, including Ohio, will jump ninefold in June to about $270 per megawatt-day.

“At a time when PJM is saying we’re facing capacity shortages, we should be doing everything we can to reduce demand,” said Rob Kelter, a senior attorney for the Environmental Law & Policy Center.

Since 2019, the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio has generally rejected utility efforts to offer widely available, ratepayer-funded programs for energy efficiency. Legislative efforts to clarify that such programs are allowed under Ohio law have been introduced but failed to pass.

In the current case, Duke Energy Ohio, which serves about 750,000 customers in southwestern Ohio, proposed a portfolio of efficiency offerings that would have cost ratepayers about $75 million over the course of three years but created net savings of nearly $126 million over the same period.

The package included energy-efficient appliance rebates, incentives for off-peak energy use, education programs for schools, and home energy assessments. The company also proposed incentives for customers who let it curtail air conditioning on hot days through smart thermostats.

In November, Duke Energy Ohio filed a proposed settlement with the PUCO staff, the Office of the Ohio Consumers’ Counsel, industry groups, and others. The terms drop all the programs for energy efficiency, except for one geared toward low-income consumers at a cost of up to $2.4 million per year. The Environmental Law & Policy Center and Ohio Environmental Council objected, as did a consumer group, the Citizens Utility Board of Ohio.

The PUCO will decide whether to approve the settlement plan by evaluating whether it benefits ratepayers and the public interest, whether it is the result of “serious bargaining” among knowledgable parties, and whether it violates any important regulatory principles or practices. Witnesses testified for and against the settlement at a hearing in January. Parties filed briefs in February and March.

Duke Energy Ohio argued in its brief that the settlement will still benefit customers and serve the public interest, even without the energy-efficiency programs for consumers who aren’t low-income. It also suggested that cutting out most of the energy-efficiency measures was needed to reach a deal with other stakeholders and the PUCO.

Staff at the PUCO said the settlement would benefit customers by cutting some projects and limiting how high other charges could go. They dismissed objections about dropping broadly available programs for energy efficiency. “[T]he standard is whether ratepayers benefit, not whether they could have benefitted more,” state lawyers wrote in their brief.

The Environmental Law & Policy Center, Ohio Environmental Council, and Citizens Utility Board of Ohio all argued there is no evidence to support dropping the energy-efficiency programs. They questioned the approach by a Consumers’ Counsel witness of counting only avoided rider costs as benefits, without considering the projected savings from energy efficiency.

The Consumers’ Counsel defended its perspective in an email to Canary Media. “We oppose subsidizing energy efficiency programs through utility rates when those products and services are already available in the competitive marketplace,” the office’s statement said. “And when the programs are run by the utility, there are added charges to consumers, such as shared savings and lost distribution revenue.” The statement also noted that other PUCO decisions have refused to allow energy-efficiency programs that would serve groups other than low-income households.

Last year, for example, the PUCO allowed FirstEnergy to run a low-income energy-efficiency program but turned down its proposal to include generally available rebates in a rider package. Those are “better suited for the competitive market, where both residential and non-residential customers will be able to obtain products and services to meet their individual needs,” the commission’s opinion said. The commission did, however, say the company should develop a rebate program for smart thermostats to help customers manage their energy use. FirstEnergy included that in its latest rider plan filed on Jan. 31.

Ohio has been particularly devoid of programs like those dropped in Duke’s settlement since HB 6 took effect, said Trent Dougherty, a lawyer for the Citizens Utility Board of Ohio. Calculations as of 2019 estimated the law’s gutting of the state’s energy-efficiency standard costs each consumer savings of nearly $10 per month.

“Continuing a pattern of wish-casting, that the market will provide the savings that HB 6 took away, is not a solution,” Dougherty said.

Airplanes. Power plants. Cars and trucks. Their images might be the first to spring to mind when thinking about the challenge posed by the energy transition.

But what about plain old buildings?

From their structural bones to the energy they constantly consume, buildings account for a staggering one-third of global carbon pollution: 12.3 gigatons of CO2 in 2022.

Most of these emissions come from their operations — the fuel burned on-site for heating and cooking and off-site to produce their electricity. But 2.6 gigatons of CO2 annually, or 7% of global emissions, stems from the carbon baked into the physical structures themselves, including the methods and materials to build them, otherwise known as embodied carbon.

A February report lays out a blueprint for tackling each of these sources of CO2 and cleaning up buildings globally by 2050. The challenge is massive: It depends on the actions of millions of building owners. But the policy and technology tools already exist to meet it, according to report publisher Energy Transitions Commission, an international think tank encompassing dozens of companies and nonprofits, including energy producers, energy-intensive industries, technology providers, finance firms, and environmental organizations.

The report identifies several key levers that must all be pulled in order to deal with the climate problems from buildings: energy efficiency, electrification, flexible power use, and design that minimizes materials and uses cleaner ones. Each is showing varying degrees of progress around the world.

“We already have so many of the solutions that we need,” said Adair Turner, chair of the Energy Transitions Commission, at a panel discussion last month. But to implement them, “we need to change minds and practices.”

Building developers and owners can pursue a variety of strategies to make their buildings less energy-intensive and cheaper to operate without sacrificing the comfort of their residents, according to the report.

They can seal air leaks; insulate attics, walls, and floors; and install double- or triple-pane windows to make buildings snug like beer cozies. Weatherization strategies that take a medium level of effort would cut 10% to 30% of energy use, according to the report; deeper changes could slash up to 60%.

For retrofits, online tools and in-person energy audits can help owners decide which changes make the biggest difference for the climate, their comfort, and their energy bills.

Other simple techniques can combat growing demand for cooling, which globally is set to more than double by 2050 due to rising temperatures and incomes, the report notes. Passive approaches that deflect the sun’s rays, from painting roofs white to planting shade-giving trees, can slash cooling needs by 25% to 40% on average.

Efficiency measures “deliver a clear return to households over time,” said Hannah Audino, building decarbonization lead at the commission.

But because the payoffs can be slow to materialize, governments should provide targeted financing to lower-income households that might not otherwise be able to afford these upgrades, she added.

There’s also the challenge of convincing landlords to invest in efficiency measures even though tenants often pay for utility bills themselves. To ensure broad uptake, the authors recommend policymakers implement building performance standards, an approach adopted by U.S. cities like New York and St. Louis to penalize building owners who fail to meet certain emissions or energy-use benchmarks.

For new builds, energy codes and other regulated standards can set a performance floor. They differ widely worldwide, but the Passive House approach is “the gold standard,” per the report. Buildings that meet its benchmarks typically slash energy use by a whopping 50% to 70% compared to conventional constructions.

What’s more, new buildings that use 20% less energy than those built merely to code usually have a “very manageable” premium of 1% to 5%, the authors write, which can be recouped in a higher sale price for developers or lower bills for owners.

Connecting buildings via underground thermal energy networks in which they share heat can also unlock big efficiency gains — and do it faster and at bigger scales than individual action might. The report notes that they “should be deployed where possible.”

Buildings will need to be fully electrified to become climate friendly. That means swapping fossil-fuel–fired equipment for über-efficient heat pumps (including the geothermal kind), heat-pump water heaters, heat-pump clothes dryers, and induction stoves.

Heat pumps are essential to decarbonize heating, which is the biggest source of operational emissions and currently only 15% electrified worldwide, according to the report. The appliances are routinely two to three times as efficient as gas equipment, and they lower emissions even when powered by grids not yet 100% clean.

Heat pumps can come at a premium, though the authors expect prices to fall as sales grow and installers gain experience. In countries with mature markets, heat pumps can even be cheaper than gas heating systems, according to the report: Take Denmark, Japan, Poland, and Sweden.

For most homes in the U.S. and many in Europe, per the report, heat pumps are cheaper to run than gas equipment and have lower total lifetime costs. Heat pumps make even more economic sense when consumers are considering installing an AC and a gas furnace; heat pumps are both in one.

These appliances also keep getting better. Manufacturers learn how to improve technologies with experience, as they have done with solar panels and wind turbines. The result is that heat pumps are becoming more efficient; getting smaller; and reaching higher temperatures as they transition to natural refrigerants (which also have lower global warming potentials), the authors write.

But policymakers need to address energy costs to encourage widespread electrification, according to the report. Countries with high electricity prices relative to those of gas lag in heat pump adoption.

Fixes include shifting environmental levies that are currently disproportionately piled onto electricity bills to gas costs, offering lower electricity rates for customers with electric heating, and putting a price on carbon, the report says. Banning gas equipment would be the most direct move, but “only a handful of countries, such as the Netherlands, have successfully outlined plans” to do so.

Buildings will need more power when they’re all-electric, potentially straining grids. Unchecked, global electricity demand for buildings by 2050 could grow 2.5 times what it is today, per the report. But with efficiency improvements, the commission expects electricity requirements to grow a more modest 45%.

That’s still massive. So, to decarbonize buildings without breaking the grid, we’ll need to make them flexible in their electricity demand, the authors note. By using power when it’s cheap, clean, and abundant, these edifices will also be more affordable than they’d be otherwise.

Low-cost smart thermostats and sensors can reduce demand by 15% to 30% and shift energy use automatically when prices drop. In some places, commercial building owners can already reap tens of thousands of dollars in annual savings by dialing down energy use when grid demand is highest.

The report recommends that all buildings aim to have the ability to shift when they actively heat or cool by two to four hours without compromising comfort. That’s doable with existing solutions that provide thermal inertia, including insulation and tank water heaters that can store hot water for when it’s needed.

Utilities and regulators can spur more flexible demand by implementing electricity rates or utility tariffs that reward customers for using power outside of peak periods.

“When the wind is blowing and the sun is shining, and we’ve arguably got an abundance of clean power on the grid, prices often go negative,” Audino said. Tariffs can reflect that reality, creating a clear financial incentive for households and others to shift their power usage. Without these more dynamic tariffs, “it’s really hard to see how we can drive this [shift] at scale.”

Building floor area globally is expected to grow by over 50% by 2050, according to the report. If structures are built with the same techniques as today, cumulative embodied carbon emissions could soar an additional 75 gigatons of CO2 between now and midcentury.

But that amount could be reduced to about 30 gigatons of CO2 by maximizing the utility of buildings that already exist, decarbonizing building materials, and designing new ones differently.

Using existing structures is “the biggest opportunity” for reducing embodied carbon, per the report: The strategy avoids adding any new embodied emissions at all. But it’s harder to implement this tactic than it is to change building techniques, the authors add.

Producing materials drives up-front emissions, and the biggest contributors are cement, concrete, and steel, the report notes: They account for 95% of the embodied carbon from materials in buildings.

Low- and zero-carbon cement, concrete, and steel can be made using electricity, alternative fuels, exotic chemistries (including ones inspired by corals), and carbon capture with storage. But developers need incentives to buy these clean materials, which aren’t yet widely available or competitive on cost alone.

A complementary approach is to design buildings with less of the emitting stuff. For the same floor space, a mid-rise structure uses less material than a high-rise, which needs a larger foundation and bigger columns. A boxy building is more efficient than an irregular one.

Developers can moreover supplement construction with alternative, lower-carbon materials, per the report. These include recycled materials, sustainably sourced timber, bamboo, rammed earth, and “hempcrete” — a low-strength, lightweight mixture of hemp, lime, and water that actually absorbs carbon.

Embodied carbon has been particularly challenging to curb because it’s largely invisible. In 2021, London regulators decided to change that, requiring major developers to tally all the carbon emissions, operational and embodied, over the building’s lifetime while still in the planning stage, the authors write.

Developers weren’t required to stay below any carbon-intensity threshold; they just had to report expected emissions, said Stephen Hill, associate director in the buildings sustainability team at firm Arup, a member of the Energy Transitions Commission.

“But it triggered a kind of race downwards in terms of embodied-carbon intensity for developers, all of whom wanted to have the lowest-carbon developments,” he added. “It’s a fascinating example of what transparency will do and how the market behaves.”

Stephen Richardson, senior impact director at the nonprofit World Green Building Council, emphasized at the commission’s panel event that to decarbonize buildings, governments need to do two things at once. “We need to incentivize, on the one hand, make it financially more appealing,” he said. And “we need to mandate.”

Large parts of Asia, most of Africa and South America, and even some U.S. states lack mandatory building codes, the report notes. And that’s the “absolute, No. 1” policy that needs to be in place, Richardson said. “Without policy, nothing happens — or very little.”

Hyundai Motor Group unveiled plans Monday for a $6 billion steel plant in Louisiana to provide the metal needed for its auto factories in Alabama and Georgia. The announcement came as part of a broader $21 billion investment into U.S. manufacturing facilities including EV factories.

Unlike much of the Midwestern, coal-based steel production that supplies the domestic automotive industry, the Hyundai Steel plant in Ascension Parish, roughly an hour west of New Orleans in the heart of the Bayou State’s so-called Cancer Alley, proposes to use an electric arc furnace. This technology is increasingly popular in the U.S. and around the world, and if powered by clean electricity it can produce steel without emitting nearly any CO2.

But electric arc furnaces can’t refine raw iron to produce “primary steel” — they rely instead on recycled scrap metal. Rather than using coal to turn iron ore into the precursor for making steel, Hyundai’s newly announced plant will likely use natural gas in the direct reduced iron (DRI) process, industry analysts say.

“Is this a step toward sustainable, green steel? Maybe not so much,” said Matthew Groch, senior director of decarbonization at the environmental group Mighty Earth. “But is it a step away from blast furnaces? Yes, which is the beginning part of transitioning the primary steel industry to low-carbon production.”

At peak capacity, Hyundai said the plant will produce 2.7 million tons of steel each year, including “low-carbon steel sheets using the abundant supply of steel scrap in the U.S.” The factory, on which construction is expected to begin later next year, will create upward of 1,300 jobs.

Hyundai made no mention of the DRI process in its press release, and a spokesperson declined to comment beyond what was in the official statement. But experts tracking the project have long expected the plant to use DRI, and an article in a Korean newspaper noted that it includes DRI. The 3.6 million tons of iron ore the Louisiana government said the plant would import each year will also need to be processed somehow, since the announced electric arc furnace won’t do the trick.

DRI with natural gas can cut carbon emissions in half compared to a coal blast furnace. Though the technology is catching on worldwide, it’s still eclipsed by traditional blast furnaces: DRI facilities accounted for about 36% of iron-making capacity under development, per a Global Energy Monitor report released last summer, but just 9% of operational capacity.

To truly produce low-carbon steel, however, the Hyundai facility would need to fuel its DRI process with green hydrogen — the version of the fuel made with completely carbon-free electricity — instead of gas, said Hilary Lewis, the steel director at climate advocacy nonprofit Industrious Labs.

As long as the Trump administration retains the 45V tax credits created by the Inflation Reduction Act, the price difference between DRI using gas and green hydrogen would be manageable. Gas-powered DRI yields steel at a levelized price of about $800 per ton, according to calculations by clean energy think tank RMI. Green hydrogen would raise the price to about $964 per ton.

Since the typical passenger car uses about one ton of steel, switching to green hydrogen instead of gas would raise the cost of manufacturing a car by less than one month of an average auto insurance payment.

“Hyundai has the opportunity to build the first truly clean iron and steel facility in the U.S.,” Lewis said. “I don’t think they should miss that opportunity. There’s still time.”

One challenge, however, is that there is little to no green hydrogen supply available in the U.S. today. Producers have struggled to get off the ground as federal policies to support production have failed to spur demand from potential customers. Earlier this year steelmaker SSAB canceled what would have been the first hydrogen-based DRI project in the U.S. after its supply partner Hy Stor Energy ran into “a series of headwinds” in the green hydrogen market.

How easily Hyundai’s plant could be retrofitted to use green hydrogen later depends on which of the two major manufacturers of DRI equipment the company ends up choosing if it goes this route.

North Carolina–based Midrex Technologies dominates the market, and its equipment would require some relatively inexpensive tweaks to use hydrogen rather than gas, Lewis said. The other major manufacturer, Tenova HYL — owned by the Buenos Aires–based Techint, with technology jointly developed with Italy’s steel giant Danieli — requires virtually zero changes to swap hydrogen for gas.

Just three existing steel plants in the U.S. use gas-powered DRI: a Cleveland-Cliffs facility in Ohio, ArcelorMittal’s Texas hub, and a Nucor production site in Louisiana. Cleveland-Cliffs is also planning to build a new DRI plant using money awarded under the Biden administration and gradually mix hydrogen in with gas as the cleanly produced version of the fuel becomes more widely available.

The fate of that project’s federal funding, and of the $6 billion the previous administration earmarked for industrial decarbonization projects in general, remains unclear as President Donald Trump has kept most Biden-era climate funding frozen.

The Seoul-based Hyundai — now the world’s third-largest automaker by sales — said the steel would supply its efforts to ramp up stateside production to 1.2 million vehicles per year. Hyundai Motor Group also owns Kia and Genesis Motor, and the combined EV sales make the conglomerate one of the biggest EV manufacturers in the country. Still, the company ranked 10th out of 18 automakers in the Lead The Charge scorecard, which examines efforts by car companies to reduce fossil fuel usage. Hyundai’s new Savannah, Georgia-based factory began churning out electric SUVs last fall.

Alongside the steel announcement, the company released plans to invest a total of nearly $15 billion in EVs, robotics, self-driving cars, renewables, and nuclear power infrastructure in the U.S.

“Hyundai will be producing steel in America and making cars in America,” Trump said at a press conference at the White House announcing the deal. He credited his recent tariff program as the main driver of the investment, though Hyundai Chairman Chung Eui-sun said at the event that the company had been working to expand its U.S. supply chain since Trump’s first term in office.

“Get ready,” Trump said. “This investment is a clear demonstration that tariffs very strongly work.”

Five years ago, San Francisco–based startup Span debuted a smartphone-controllable electrical panel that allows homeowners to manage their solar panels, backup batteries, EV chargers, HVAC systems, and other major household appliances in real time. It was a high-end product for a high-end market.

But as more households purchase EVs, heat pumps, induction stoves, and other power-hungry devices, the demand for cheaper ways to control their electricity use is growing — not just from homeowners trying to avoid expensive electrical upgrades but utilities struggling to keep up with rising power demand, too.

Enter the Span Edge, unveiled at the Distributech utility trade show in Dallas this week. The device packs the startup’s core technology into a package that can be installed in about 15 minutes and plugged into an adapter that connects to a utility electric meter.

Span’s other products are targeted at homeowners; electrical contractors; and solar, battery, and EV charging installers. But the Span Edge, which requires a utility worker to install, is “expanding way beyond a homeowner or installer-led adoption of the product, to becoming part of the utility infrastructure,” said CEO Arch Rao.

That makes it one of a growing number of tools for utilities to manage the solar, batteries, EVs, controllable appliances, and other distributed energy resources that they must increasingly plan around.

If utilities manage these resources reactively, they could drive up the cost and complexity of managing the grid. But if utilities can get better information about when and how these devices use power — and if some customers are willing to adjust them sometimes to reduce grid stress — they could actually save ratepayers a lot of money.

That’s what Span’s new technology aims to allow. The company’s “dynamic service rating” control scheme can throttle or shift power use between household electrical loads, based on a homeowner’s preset or real-time priorities. That helps ensure total draw on the utility grid stays below a home’s top electrical service capacity, which typically ranges between 100 and 200 amps.

Households that want to exceed the limit of their electrical panel are often forced to upgrade to a larger one. Depending on where you live, that can cost from $3,000 to $10,000 and add days to weeks of extra time to a project, like installing an EV charger. If a utility determines a home’s new maximum power draw will trigger grid upgrades, the project could be even more expensive and take much longer to complete. In the worst case, that could kill households’ plans to do everything from switching to an EV to electrifying their heating and cooking.

It’s also expensive for utilities. “Where consumers are adding heat pumps and EV chargers, the existing solution has always been, ‘Let’s build more infrastructure — more poles and wires — to meet the maximum load,’” Rao said.

Installing a device like the Span Edge could well be a more cost-effective alternative, not just for the customers who get one but for customers as a whole. Utility rates are largely determined by dividing the amount of money earned from electricity sales by the amount of money utilities have to collect from customers to cover their costs. A big and rising portion of U.S. utility costs is tied up in upgrading and maintaining their power grids, including to meet rising demand for power from EVs and heat pumps. As a result, ratepayers in many parts of the country are seeing higher bills.

If devices like the Span Edge can cut those grid costs while allowing people to buy more electricity for EVs and heating, rates for everyone will drop over time, Rao said. While some utilities may balk at replacing profitable grid-upgrade investments with new technology, others that want customers to electrify to meet carbon-reduction mandates or to increase electricity sales may be eager to implement it, he argued.

Span’s smart electrical panel was among the first attempts to give the old-fashioned electrical panel a 21st-century makeover.

But similar products that also embed circuit-level controls are now available from major manufacturers, including Schneider Electric and Eaton; startups such as Lumin and Koben; and solar and battery vendors like FranklinWH, Lunar Energy, and Savant.

Utilities have been experimenting with such technologies for a while. Some plug directly into utilities’ existing electric meters, including the Span Edge, ConnectDER’s smart meter collar devices, or the Tesla backup switch.

Others are embedded elsewhere in a home’s electrical system, like the controls product startup Lunar Energy is developing using Eaton’s smart circuit breakers. Those digital, wirelessly connected breakers are “modular, interoperable, and retrofittable,” Paul Ryan, the company’s general manager of connected solutions and EV charging, told Canary Media in October. That’s helpful “as you add heat pumps and electric vehicle charging,” he said — and could be useful for utilities, a group of customers Eaton has worked with for many years.

The trick for all of these technologies is to combine the convenience and simplicity consumers demand with utility safety and reliability requirements, said Scott Hinson, chief technology officer of Austin, Texas–based nonprofit research organization Pecan Street.

In a 2021 report, Pecan Street estimated that about 48 million U.S. single-family homes with service below 200 amps might need to upgrade their electrical panels to support electric heating, cooking, and EV charging.

But not all of the technologies that allow customers and utilities to sidestep upgrades necessarily meet the needs of both parties, he said.

Take the smart-home platforms on offer from Amazon, Apple, Google, Samsung, and other tech vendors, which can control light bulbs, thermostats, ovens, refrigerators, and a growing roster of other devices. These systems rely on WiFi and broadband connections, and that’s not good enough to let households skip upgrading their electrical panels, Rao pointed out. The latest certifications for power control systems require fail-safes that work even when the internet is down, something Span’s products do by sensing overloads and shutting down circuits.

On the other hand, rudimentary on-off control switches are far from ideal, Hinson said.

“A lot of these devices don’t like to be controlled” by having their power cut off externally in such a rough-and-ready manner, he added. For example, abrupt power cutoffs trigger the “charging cord theft alert” feature in EVs like the Chevy Volt, which starts the car alarm until the owner shuts it off — not a pleasant experience for the EV owner or neighbors.

More importantly, Hinson said, a good system needs to control “large loads so they’re aware of each other,” he said. Homeowners want to control which appliances get shut off when the need arises, whether it’s their EV charger, clothes dryer, oven, or heating and cooling, he said. But to do that, “the car has to know what the electric oven is doing, which has to know what the heater is doing.”

Span’s devices have two ways to do this, Rao said. Because they contain the connection points for power to flow through circuit breakers to a home’s electrical wiring, the devices can directly measure how much power household loads are using — and cut them off completely in an emergency.

At the same time, Span uses WiFi or other technologies to communicate with “smart” heat pumps, water heaters, EV chargers, and other devices, he said. That allows households to control the power that devices get on a more granular scale as well as collect information beyond how much power they’re using, such as when an appliance is scheduled to turn back on or, for EVs, how quickly they need to be recharged to give the driver the juice they need to get to where they’re going next.

What’s important is that a system can provide both options, Rao contended. “If you only did on-off control, the customer experience is bad,” he said. “If you only did WiFi, you’re not safe enough for the grid.”

Having both visibility into and control over home electricity flows creates the groundwork for a more flexible approach to enlisting homes in utility virtual power plants, or VPPs. In simple terms, VPPs are aggregations of homes and businesses that agree to turn down power use or inject power onto the grid as utilities need, helping reduce reliance on large centralized power plants.

Most of the virtual power plants that exist today are organized around individual devices — smart thermostats that can reduce electricity demand from air conditioning, for example, or solar-battery systems that can send power back to the grid. Each of these technologies has its limitations, and utilities’ reliance on them is often constrained by a lack of precise data on how much power the grid is using or can offer at any particular time.

A system that tracks the energy use of multiple appliances and devices in a home could bring far more precision to these VPPs, Rao said. “That’s very different than the demand-response world, where you call a thermostat and say ‘I hope it responds to me.’”

Utilities certainly have a growing interest in using these kinds of devices. On Monday, Pacific Gas & Electric announced a new VPP pilot program that seeks to enlist customers willing to allow the utility to control their “residential distributed energy resources to reduce local grid constraints.”

PG&E is looking for up to 1,500 electric residential customers with battery energy storage systems and up to 400 customers with smart electric panels. Its partners include leading U.S. residential solar and battery installer Sunrun, which has done VPP pilots with the utility in the past, and Span, which will use its technology to allow homes to respond to utility signals.

Span has already tested this capability in a pilot project enlisting customers who’ve installed the company’s smart panels in Northern California, Rao said. The results so far are promising, although only a handful of households are taking part.

Getting utilities to deploy Span Edge devices could expand the scale of those kinds of programs, he said. Of course, households will have to agree that letting some of their electricity use get turned off or dialed down during hours of peak grid stress is worth avoiding the cost and wait times of upgrading their electrical service to get the EV charger or heat pump they want.

Span hasn’t revealed the cost of the Span Edge, which Rao said will soon be deployed in pilot projects with as-yet unnamed utilities. The company has a partnership with major smart-meter vendor Landis+Gyr, which is offering the Span Edge to its utility customers.

The question for utilities, regulators, and other stakeholders is whether the long-term payoff in avoided infrastructure upgrades is worth the cost of the technologies that must be deployed to make that possible. Those calculations will inform decisions such as whether customers getting the technologies should pay a portion of the price tag and how much profit utilities should be allowed to earn on the costs they bear in installing the tech.

PG&E’s chief grid architect, Christopher Moris, said the Span Edge device “is a potential solution which may be able to, at a reduced cost, enable customers to connect their EV and transition off of gas.” One of the utility’s biggest near-term challenges is helping customers install EV chargers, he noted. PG&E has more than 600,000 EVs in its service territory, almost certainly more than any other U.S. utility.

The company also faces customer and political backlash to its recent rate hikes, a problem driven by its need to carry out more and costlier power grid upgrades. While devices like the Span Edge could help address that problem, “we realize how new such a concept is for our customers,” Moris said.

“I’m very bullish on this new solution — but we don’t know what we don’t know,” he said. PG&E “will need to go through a customer discovery process to really understand their challenges more first, before definitely landing on the Span solution and, if so, what the end-to-end solution looks like.”

A clarification was made on March 26, 2025: An earlier version of this article implied that Lunar Energy and Eaton are co-developing a home energy controls product, and that Eaton is testing its AbleEdge circuit breakers for use by utilities. In fact, Lunar Energy is integrating Eaton’s AbleEdge smart breakers into Lunar Energy’s home energy controls platform, and while Eaton has worked with utilities in the past, it has yet to test its AbleEdge devices with utilities.

The batteries inside electric vehicles can do a lot more than power a car.

They can back up homes, schools, and businesses during power outages. They can soak up grid power when it’s plentiful and cheap and send it back when it’s scarce and costly. And they could eventually provide enough reliable power to allow utilities to avoid building more power plants or expanding their grids to meet growing demand for electricity — something that would save money for utility customers as a whole.

So far, utilities have had a hard time turning this dream of batteries on wheels into a reality. Plenty have launched these “vehicle-to-everything” (V2X) pilots, but only with mixed success. Broader adoption has been held back by the cost and complexity of getting the required technologies to work smoothly in the real world — and by an absence of well-established utility programs that pay EV owners enough to make it worth their while.

In Massachusetts, a new V2X pilot project is now seeking households, businesses, schools, nonprofits, and municipal governments to test all of these ways that EVs can help the grid. And unlike many V2X tests done by other U.S. utilities, this one will offer two key financial incentives: bidirectional chargers at no cost to participants, and real money to those who commit to letting utilities tap into their EV battery power.

Over the next nine months, the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, the state’s clean-energy economic development organization, will use most of the pilot’s $6 million in funding to give out up to 100 free bidirectional chargers. This is the technology that allows EV owners to not only pull electrons from the grid but to send power back and get paid for it. Households will get most of this equipment, but a subset of higher-voltage two-way chargers will go to commercial vehicle and electric school bus fleet operators.

Those chargers will be installed by September 2026, said Elijah Sinclair, MassCEC clean transportation program manager. The goal is for the pilot to provide about 1.5 megawatts of distributed energy storage capacity, roughly equivalent to the power use of about 250 homes.

Massachusetts law calls for 900,000 EVs on the road by 2030 in order to meet the state’s decarbonization goals. If a well-designed pilot project unlocks cost-effective ways or even a fraction of those future EV owners to enlist in V2X programs, the payoff could be huge, Sinclair said. EVs tend to stay plugged in far longer than it takes to fully charge up their batteries. Being able to tap into that stored energy expands the value that EVs can provide the grid and allows them to store solar and wind power to use later when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining.

“That could be a really important piece as we seek to get to net-zero by 2050,” Sinclair said. “It still requires a whole lot of infrastructure, and it’s complicated for the utilities. But in the future, it could be serving huge loads across the grid.”

The trick is to move from the experiment stage to a safe, simple, and profitable program for a majority of the state’s EV owners, he said. It’s not something any other state or utility has managed to pull off just yet — but MassCEC and its partners are hoping the upcoming pilot will build the foundation to make that happen.

The idea of pulling power from EV batteries is far from new. Universities and research organizations have been successfully testing V2X for more than two decades, and U.S. utilities have had pilots up and running for years.

Other countries have more fully embraced the technology. Japanese automakers started enabling EVs to provide backup power via vehicle-to-home and vehicle-to-building charging to deal with the power supply emergencies that followed the 2011 Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster. In Europe, vehicle-to-grid (V2G) projects have been turning a profit for commercial and government vehicle fleets for years, and more recently for consumer EVs as well.

In the U.S., by contrast, vehicle-to-grid services have largely been successful in just one niche of the EV market: electric school buses, which happen to sit unused during most of the day. In Massachusetts, the company Highland Electric Fleets and the city of Beverly have been doing V2G with school buses since 2020, and have been earning money for delivering extra power to utility grids over the past few summers.

Transit and commercial vehicles, which must be on the road more frequently and have less idle time to charge, are more challenging to make profitable.

Vehicle-to-home backup power, meanwhile, has been built into the Nissan Leaf for more than a decade, and has been a major marketing draw for the Ford F-150 Lightning electric pickup and other new EV models. But actually engineering and installing the systems to turn a home EV charging system into a backup power system for the grid is a bit more complicated — and costly.

So said Kelly Helfrich, who leads the transportation electrification practice at Resource Innovations, a company specializing in clean-energy program implementation that is co-leading the MassCEC V2X program. She’s worked in the EV space for more than a decade, including a stint at General Motors that covered the automaker’s entry into vehicle-to-grid technology and its eventual development of V2G standards.

Bidirectional chargers are more costly and technically difficult to build compared to simple one-way chargers. That investment may well be worth it for school buses, which have big batteries that can earn lots of money while they’re sitting idle. But for everyday households, it’s harder to see a path to recouping the extra $5,000 to $10,000 in up-front costs that bidirectional equipment can bring, Helfrich said.

Installing free chargers for homeowners, as the MassCEC program is doing, “helps take that cost out of the equation,” she said, “to really test vehicle-to-home at a larger scale than we’d be able to if we were to rely on consumers to take on that expense.”

Successful V2X programs also need to make sure participants get paid for taking part.

On that front, Massachusetts already has an established program that lets EV owners earn money by helping the grid, according to Zach Woogen, executive director of the Vehicle-Grid Integration Council, a group representing EV and charging manufacturers that’s working with utilities and regulators across the country.

ConnectedSolutions is a long-running offering from utilities National Grid and Eversource, which operate in Massachusetts and other New England states. The program pays customers for reducing grid strain during hours of high demand for electricity, usually during hot summer afternoons and evenings.

ConnectedSolutions already pays EV owners who avoid charging during those hours, Woogen said. It also allows customers to earn money for power they send back to the grid from batteries attached to their rooftop solar systems — or, more recently, from EVs in fleets owned by businesses, schools, or governments.

Tapping into the collective flexibility of batteries, EV chargers, rooftop solar, remote-controllable thermostats, and other devices to create “virtual power plants” could unlock gigawatts of capacity across the country. Companies targeting these opportunities have given ConnectedSolutions high marks for its relatively straightforward rules and lucrative payments.

Right now, the program doesn’t allow residential EVs to send power back to the grid, Woogen noted. But it could allow homes to reduce their grid draw by supplying part of their own electricity use during times of peak demand, or explore other opportunities to reward households for making their vehicles available when power demand is highest.

A handful of other utility V2X programs are paying households for their EV battery power. California utility Pacific Gas & Electric has a V2X pilot that pays participants and recently expanded it to support up-front installation costs for General Motors EV-compatible bidirectional chargers. But PG&E’s compensation structure is tied up in a more complicated dynamic pricing pilot program with less certain long-term prospects than the ConnectedSolutions initiative, Woogen said.

Other programs offer easy-to-understand and lucrative payments to customers but don’t take on the high up-front cost of setting up bidirectional charging. Maryland utility Baltimore Gas & Electric launched a program last year that offers up to $1,000 a month for owners of Ford F-150 Lightning electric pickups who let the utility tap their batteries during grid peaks. But few customers have installed the necessary bidirectional charger and control systems, which cost roughly $9,000.

Government incentives can’t keep bankrolling EV owners to install V2X equipment forever, of course. But they’re vital to getting enough customers to sign up so that utilities can test the real-world effects, costs, and benefits of tapping those EV batteries at a scale that really affects the grid.

Incentives also encourage automakers, charging system manufacturers, and software providers to work with utilities on making V2X technologies ready for prime time, Woogen said. “We’re at an early stage of the market — and we don’t yet have that competition to drive down costs for customers.”

The Vehicle-Grid Integration Council’s role in the MassCEC pilot is to organize all these industry participants and to track progress. The first and most fundamental goal, Woogen said, is determining whether bidirectional chargers can “safely and reliably connect with the grid in a way that’s reasonably low-cost and reliable and fast.”

That’s a work in progress, he said. Over the past decade or so, a growing list of charging equipment has been approved for installation by a subset of U.S. utilities working on V2X. New developments are making it possible for EVs themselves to push power back to the grid without a bidirectional charger, although automakers and utilities haven’t gotten to the point of allowing EV customers to use that technology outside of strictly controlled settings.

Utilities have to be sure that hooking high-voltage EV batteries into buildings and the grid is safe before they can let it happen at large scale, Helfrich said. Resource Innovations has longstanding relationships with National Grid and Eversource, and is working with the state’s other investor-owned and municipal utilities as well, she said.

MassCEC has also partnered with an experienced V2X technology partner to select and install the 100 bidirectional chargers. That’s The Mobility House, a German company with technology now in use in large-scale fleet charging projects as well as in Europe’s first mass-market residential V2G program.

“For this project, we’re acting as the technology expert,” said Russell Vare, Mobility House’s vice president of vehicle-grid integration. “That means bringing the right hardware and the software to do both the control for the energy and the aggregation and optimization.”

It also means tracking some far more prosaic data points that are important for V2X, he said. Take the inherently mobile nature of an EV battery — ”Is the car driving around, or is it plugged in?” That’s a big deal when a utility needs to know exactly how much EV battery capacity it can rely on for an upcoming demand peak.

Then there’s the to-be-collected data on how much money it takes to convince customers to use their EV as a backup battery or to allow it to be used to help the grid, Vare said. “How large does that value need to be to encourage them to participate?”

That’s important information for state agencies and utilities to have on hand as they plan out the next phases of their V2X efforts, Woogen said — and it’s an important part of the pilot project. The Vehicle-Grid Integration Council and consultancy Converge Strategies will collect feedback from automakers, charging vendors, utilities, local governments, community members, and the customers who get the 100 bidirectional chargers over the course of the pilot.

That work is meant to inform a guidebook by the end of next year that can inform policymakers and utilities looking at how to build V2X into their clean energy strategy, Helfrich said — not just in Massachusetts but around the country.

“It’s going to be a documentation of everything we designed for this two-year program,” she said — “what went well, what did not go well, and what should be considered in moving these programs to a more mature scale.”

The U.S. hit a major energy-transition milestone last year: For the first time ever, it produced more electricity from wind and solar than from coal.

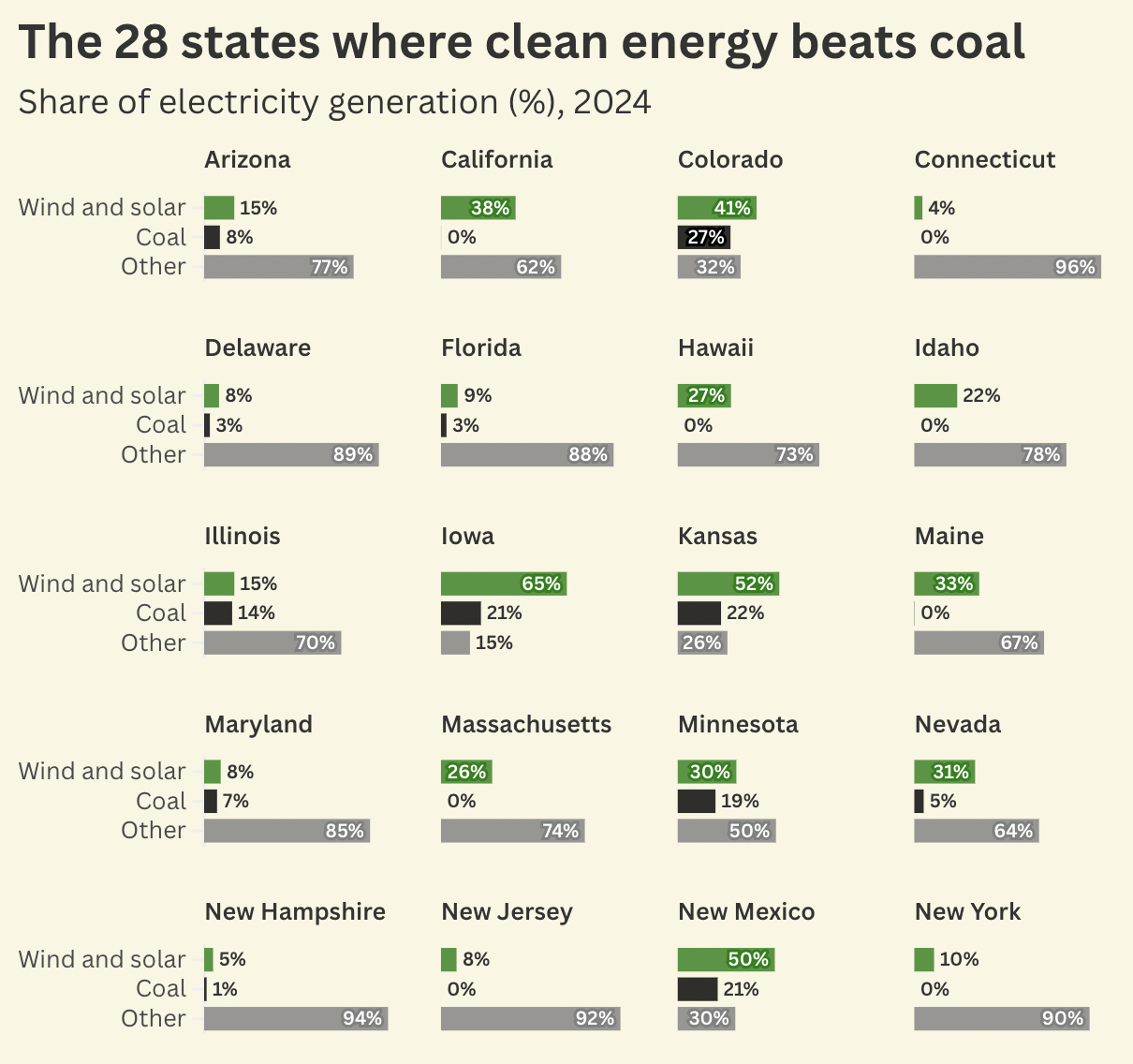

Over half of U.S. states now get more power from breeze-blown turbines and sun-soaked photovoltaic panels than they do from polluting, planet-warming coal, according to a new report from think tank Ember.

Coal is the most environmentally destructive source of electricity available. For a long time, it was the most widely used power resource in the U.S., too.

Two decades ago, the country got about half of its electricity from coal-fired power plants. Today that number is just 15%. Wind and solar have ascended over the same time period. Together they now produce 17% of U.S. electricity, and solar is set to lead power capacity additions again this year.

Beyond their climate benefits, renewables beat coal on economics. A 2023 report found that all but one U.S. coal plant could be cost-effectively replaced by a combination of solar, wind, and batteries, though that finding relied on Inflation Reduction Act tax credits that some Republican lawmakers want to repeal.

The rise of cheap fossil gas spurred by the fracking boom has also played a key role in phasing out coal. Gas use has soared in the decades that coal has declined; it alone produced nearly 43% of U.S. power last year.

In 2025 the U.S. Energy Information Administration expects that 8.1 gigawatts worth of coal will be retired from the grid — equal to nearly 5% of the nation’s operating coal fleet as of 2024. Over the next five years, 120 coal plants are slated to shutter, helping reduce the carbon intensity of electricity and air pollution for local communities.

In other words, the yearslong decline of coal is set to continue. Unless, that is, the Trump administration’s burgeoning effort to rescue the industry succeeds.

Energy Secretary Chris Wright and Interior Secretary Doug Burgum both said last week that the government is working to halt coal plant closures. And just this week, President Donald Trump wrote on Truth Social that he is authorizing his administration “to immediately begin producing energy with BEAUTIFUL, CLEAN COAL.”

No specific plans have yet been announced.

Speaking to fossil fuel executives and other energy leaders at the CERAWeek conference last week, U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright made a bold claim.

“Everywhere wind and solar penetration have increased significantly, prices on the grid went up and stability of the grid went down,” he said.

But that claim is“not borne out by the data at all,” Robbie Orvis, the senior director of modeling and analysis for nonpartisan think tank Energy Innovation, told Canary Media’s Jeff St. John. In fact, a report out Thursday from Orvis and his colleagues found that clean energy is key to keeping U.S. electric bills in check.

The analysis looks at what would happen if congressional Republicans succeed in repealing the Inflation Reduction Act tax credits that have helped supercharge clean energy adoption in the U.S. The result of such a repeal? Dirtier air, more carbon emissions — and higher power bills. The average household’s energy bills would rise $48 per year by 2030 and $68 by 2035. Three other recent studies echo Energy Innovation’s findings, including one released Thursday by Rhodium Group.

The reason bills would rise is straightforward: Cutting IRA incentives would discourage the construction of solar and wind, which have become the cheapest sources of new power generation over the past decade.

Aside from electricity cost, clean energy boasts several other economic advantages over fossil fuels. A 2023 Energy Innovation report found that 99% of the country’s coal plants could be cost-effectively replaced with wind, solar, and batteries. The industry is also a growing employer, with jobs in clean energy expanding at more than twice the rate of the country’s entire job market in 2023. And numerous studies show that curbing fossil fuel use drastically reduces particulate matter and other air pollutants, which in turn helps people avoid health care costs.

Those benefits — specifically lower energy costs and job creation — are why a group of Republican Congress members are pushing to keep IRA incentives in place. Some conservative advocates and business leaders are joining them and making a case that clean energy is the cheapest, quickest way to achieve the “energy dominance” President Donald Trump is looking for.

Two clean energy projects get Trump’s green light

The U.S. Energy Department on Monday sent a $56.8 million loan disbursement to Holtec’s Palisades nuclear plant in Michigan, which will help the company restart the shuttered facility. It’s just a tiny first slice of the up to $1.52 billion loan Holtec could receive, but it indicates the Trump administration supports the Biden-era project even as many others remain in question. The federal Bureau of Land Management also approved a transmission line that will serve a utility-scale solar project in southern California — and went so far as to say the project will support “American Energy Dominance.”

But don’t expect a clean-energy change of heart just yet. Federal funding uncertainty still has dozens of projects in the lurch, including a Louisiana community solar program and a plan to transform a New York City fossil-fuel power plant into a hub for wind, geothermal, and storage.

How the Russia-Ukraine war sped up Europe’s clean transition

It’s been three years since Russia invaded Ukraine and upended Europe’s energy system. In the wake of the invasion, the EU rapidly reduced its reliance on Russian fossil gas by building renewables, shifting to electric heat, and sourcing liquefied natural gas from the U.S., Canary Media’s Julian Spector reports. The continent’s overall gas use fell during that time, with mild winters and higher fuel prices playing a role as well. Analysts say it’s clear the war sped up the transition — and a lot of that gas demand won’t be coming back.

Bird’s-eye view: The Nature Conservancy, Planet, and Microsoft use satellite imagery to map large-scale solar and wind installations around the world. (New York Times, Global Renewables Watch)

Green bank update: A federal judge temporarily blocks the U.S. EPA from taking back $20 billion inBiden-era “green bank” funding this week, though nonprofits won’t yet be able to access that money. (Politico)

Heat-pump road map: California is the first in the nation to create a statewide heat-pump deployment plan, which will help it meet its goal of installing 6 million electric heat pumps by 2030. (Canary Media)

Where renewables beat coal: The U.S. got more of its electricity from wind and solar than from coal last year, with renewables beating out the fossil fuel in 28 states. (Canary Media)

Super Soakers to super batteries: An Alabama entrepreneur who developed the Super Soaker water gun is using proceeds from his inventions to develop a new battery he says doesn’t require the same cooling systems as lithium-ion batteries. (Forbes)

Supersonic charging: Chinese company BYD announces a charging technology it says could“fill up” an EV in just five minutes — a development that could reinvigorate U.S. charger investment. (Axios)

Vermont’s climate battle: Vermont has long built a reputation as a climate leader, but its Democratic lawmakers face an uphill battle to pass more clean energy measures this session as Republican Gov. Phil Scott attempts to roll back parts of the state’s landmark climate law. (Canary Media)

By this time next year, a new satellite will be detecting how much methane is leaking from oil and gas wells, pumps, pipelines and storage tanks around the world — and companies, governments and nonprofit groups will be able to access all of its data via Google Maps.

That’s one way to describe the partnership announced Wednesday by the Environmental Defense Fund and Google. The two have pledged to combine forces on EDF’s MethaneSat initiative, one of the most ambitious efforts yet to discover and measure emissions of a gas with 80 times the global-warming potential of carbon dioxide over a 20-year period.

MethaneSat’s first satellite is scheduled to be launched into orbit next month, Steve Hamburg, EDF chief scientist and MethaneSat project lead, explained in a Monday media briefing. Once in orbit, it will circle the globe 15 times a day, providing the “first truly detailed global picture of methane emissions,” he said. “By the end of 2025, we should have a very clear picture on a global scale from all major oil and gas basins around the world.”

That’s vital data for governments and industry players seeking to reduce human-caused methane emissions that are responsible for roughly a quarter of global warming today. The United Nations has called for a 45 percent cut in methane emissions by 2030, which would reduce climate warming by 0.3 degrees Celsius by 2045.

EDF research has found that roughly half of the world’s human-caused methane emissions can be eliminated by 2030, and that half of that reduction could be accomplished at no net cost. Emissions from agriculture, livestock and landfills are expected to be more difficult to mitigate than those from the oil and gas industries, which either vent or flare fossil gas — which is primarily methane — as an unwanted byproduct of oil production, or lose it through leaks.

That makes targeting oil and gas industry methane emissions “the fastest way that we can slow global warming right now,” Hamburg said. While cutting carbon dioxide emissions remains a pressing challenge, “methane dominates what’s happening in the near term.”

Action on methane leakage is being promised by industry and governments. At the COP28 U.N. climate talks in December, 50 of the world’s largest oil and gas companies pledged to “virtually eliminate” their methane emissions by 2030, Hamburg noted. The European Union in November passed a law that will place “maximum methane intensity values” on fossil gas imports starting in 2030, putting pressure on global suppliers to reduce leaks if they want to continue selling their products in Europe.

In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency has proposed rules to impose fines on methane emitters in the oil and gas industry, in keeping with a provision of 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act that penalizes emissions above a certain threshold. And in December, the EPA issued final rules on limiting methane emissions from existing oil and gas operations, including a role for third-party monitors like MethaneSat to report methane “super-emitters” — sources of massive methane leaks — and spur regulatory action.

Accurate and comprehensive measurements are necessary to attain these targets and mandates, Hamburg said. “Achieving real results means that government, civil society and industry need to know how much methane is coming from where, who is responsible for those emissions and how those emissions are changing over time,” he said. “We need the data on a global scale.”

That’s where Google will step in, said Yael Maguire, head of the search giant’s Geo Sustainability team. Over the past two years, Google has been working with EDF and MethaneSat to develop a “dynamic methane map that we will make available to the public later this year,” he said during Monday’s briefing.

EDF and Google researchers will use Google’s cloud-computing resources to analyze MethaneSat data to identify leaks and measure their intensity, Maguire said. Google is also adapting its machine-learning and artificial-intelligence capabilities developed for identifying buildings, trees and other landmarks from space to “build a comprehensive map of oil and gas infrastructure around the world based on visible satellite imagery,” he said — a valuable source of information on an industry that can be resistant to providing asset data to regulators.

“Once those maps are lined up, we expect people will be able to have a far better understanding of the types of machinery that contribute most to methane leaks,” Maguire said. These maps and underlying data will be available later this year on MethaneSat’s website and from Google Earth Engine, the company’s environmental-monitoring platform used by researchers to “detect trends and understand correlations between human activity and its environmental impact.”

The work between Google and EDF on MethaneSat is part of a broader set of methane-emissions monitoring efforts by researchers, governments, nonprofits and companies. At the COP28 climate summit, Bloomberg Philanthropies pledged $40 million to support what Hamburg described as an “independent watchdog effort” to track the progress of emissions-reduction pledges that companies in the oil and gas industry made at the event.

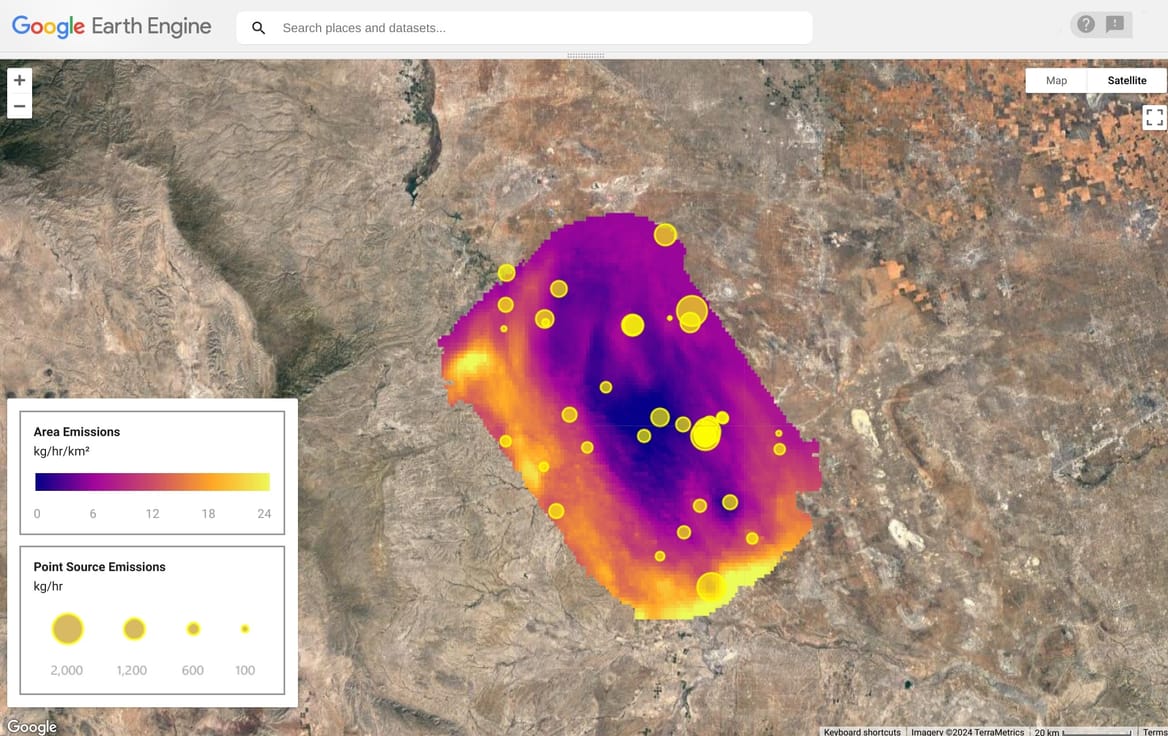

MethaneSat will bring new technology to the table, he said. Its sensors can detect methane at concentrations of 2 to 3 parts per billion, down to resolutions of about 100 meters by 400 meters. That’s a much tighter resolution than the methane detection provided by the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel satellite, which nonetheless has been able to detect gigantic methane plumes in oil and gas basins in Central Asia and North Africa in the past three years, he said.

At the same time, MethaneSat can scan 200-kilometer-wide swaths of Earth as it passes overhead, he said. That combination of detail and scope will allow it to “see widespread emissions — those that are across large areas and that other satellites can see — as well as spot problems where other satellites aren’t looking.”

This image, taken from a scan using MethaneSat’s sensors in an airplane flying over the Permian Basin, the major oil- and gas-producing region in West Texas and eastern New Mexico, shows the combination of area emissions and point-source emissions that the sensor can capture.

EDF’s work with Google is also enabling the use of MethaneSat data to detect not only the concentration of methane in the atmosphere but also its “flux,” he said — the volumes of methane leaking and their change over time. That’s important information for government regulators seeking to quantify leakage rates to impose penalties or measure industry mitigation efforts, he noted. “We’re telling everyone the information they need to take action, as opposed to scientific information that requires further processing.”

Hamburg pointed to other satellite, aerial and ground-based monitoring technologies that can provide more fine-grained data on which parts of oil and gas infrastructure are the source of individual leaks, so that “any individual company or actor in a specific spot can make a repair.”

This granular monitoring is being provided today by Canadian-based company GHGSat, which can focus its sensors to collect data from a point on the Earth as small as roughly 25 meters square. It will be aided by Carbon Mapper, a joint effort of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, the California Air Resources Board, private satellite company Planet, and universities and nonprofit partners including RMI and Bloomberg Philanthropies. (Canary Media is an independent affiliate of RMI.)

Later this year, Carbon Mapper plans to launch into orbit two satellites that will be able to deliver 30-meter-square resolution of point-source methane emissions.

“What Carbon Mapper is focused on is how to discover and isolate super-emitters,” Riley Duren, CEO of the public-private consortium, told Canary Media in a December interview.

Duren compared Carbon Mapper to “a collection of telephoto lenses, zooming in to give you a single view.” MethaneSat, by comparison, is “regional accounting, wall to wall, all the emissions in the Permian Basin or Uinta Basin,” or other oil- and gas-producing regions, he said.

“This has to be a system of systems,” he added. “No one technology will solve this.”

MethaneSat has spent $88 million on the design, construction and launch planning for its first satellite, Hamburg said. The work is funded by a $100 million grant from the Bezos Earth Fund, the philanthropic organization launched by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos.

MethaneSat’s data will be open to analysis from “scientists around the world to validate, to make sure that everybody understands what it can do and what it can’t do,” he added.

Maguire noted that the data from Google Earth Engine, including the MethaneSat data it will make available later this year, is “available to researchers, nonprofits and academic institutions for free.” He noted that oil and gas companies will also be able to access the data to inform their own methane leak mitigation efforts. While Google doesn’t have “any information to share at this point” about if or how it might charge companies for that data, “our goal is to make sure that this information is as broadly accessible as possible.”

As for how regulators might make use of MethaneSat data, Hamburg said the organization is “working with the global community of scientists and talking with governments about how to utilize these data to effectively drive the change they’re looking to drive.” He declined to provide specifics on what those conversations with governments have entailed. “I wouldn’t call them formal talks, but active talks,” he said.

It’s become the animating question in the U.S. electricity industry: How can power-hungry data centers get the energy they need?

The obvious answers have proven insufficient. Solar and wind power projects face yearslong wait times to interconnect to constrained grids. Moves to siphon off existing nuclear power to avoid these grid bottlenecks have proven controversial. And building new fossil gas–fired power plants will not only worsen climate change but may simply be impossible on the timeline that data centers require given current gas turbine backlogs.

But there may be faster and cheaper ways to bring lots of clean energy online to match new data center demand — it just requires some creative thinking.

One idea is to couple new clean power with some of the dirtier, if only rarely used, fossil-fuel power plants already connected to the grid — an approach that, counterintuitively enough, could end up not just faster but cleaner than alternatives.

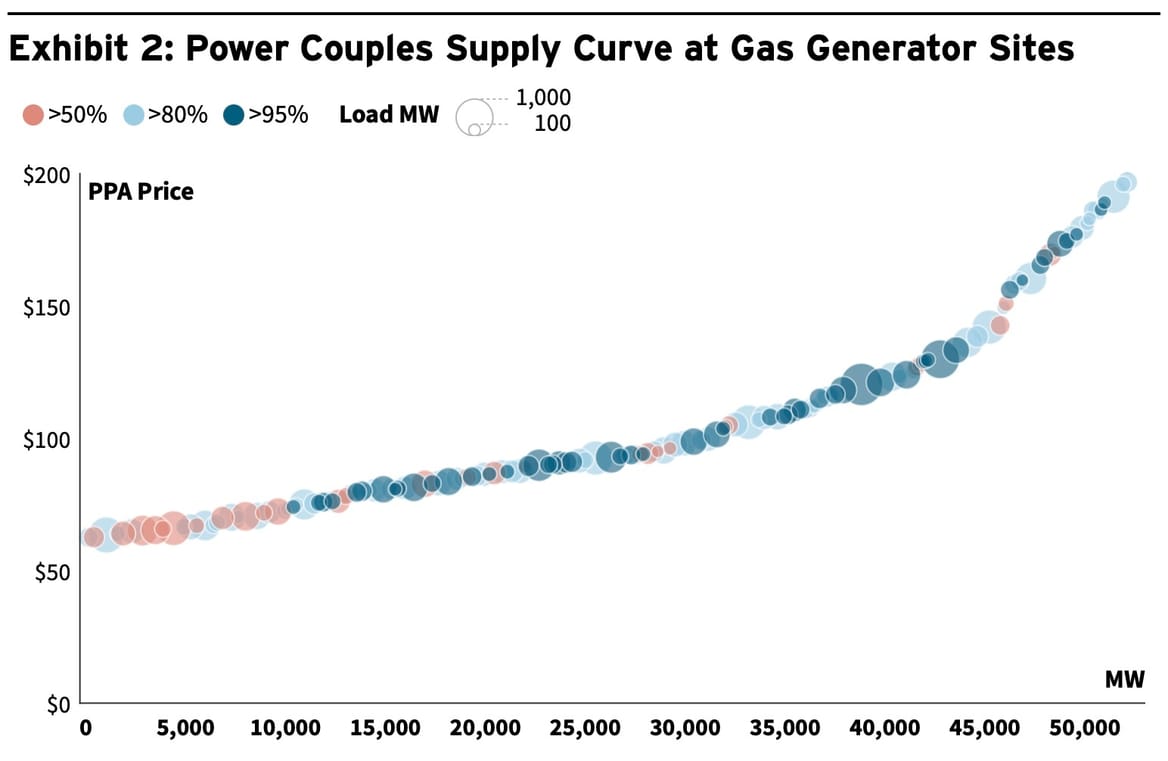

That’s the proposition think tank RMI lays out in a recent paper describing the potential for so-called “power couples,” which the authors define as lots of new solar, wind, and batteries connected to existing fossil gas–fired “peaker” plants, which basically act as emergency generators for the grid at large, all in service of a data center or other facility that uses large amounts of power.

The biggest data centers now being planned across the country by tech giants like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft can use hundreds of megawatts to gigawatts of electricity. In some of the country’s biggest data center hot spots, there simply isn’t enough capacity left to connect that much new load right now.

But in the “power couple” structure, those data centers wouldn’t even draw from the grid, explained Uday Varadarajan, a senior principal at RMI’s carbon-free electricity program and co-author of the report. Instead, they’d be connected to clean power behind the “point of interconnection” between peaker plants and the grid at large.

That could also allow new large-scale clean power projects to connect directly to the data center. Some of those solar, wind, and battery developments are already permitted and awaiting grid interconnection — and all of them can be built much faster than new gas-fired power plants, according to industry experts. Allowing some of these projects to avoid the interconnection backlogs and grid upgrade costs would get clean power online much faster.

Of course, few if any data centers can rely solely on the sun and wind to serve their round-the-clock power needs, even with batteries to store some of that power for when demand is highest. That’s where the peaker plant comes in, Varadarajan said.

Peaker plants can serve as a circuit breaker of sorts between the grid on one side and the new data center and all its clean power and batteries on the other side. When there’s not enough clean power for the data center, “we allow the new load to draw from the existing gas plant in a limited way,” he said. The key is making sure the data center doesn’t impinge on when the grid needs that peaking power.

In that sense, the peaker plants are more like gas-fired backups for a largely clean power mix. It’s a natural fit: Peaker plants are designed to fire up only when the grid really needs them, largely during summer heat waves or winter cold snaps when demand for electricity peaks (hence their name).

That leaves a lot of hours when those plants aren’t using their connections to the grid at large — which creates an opening for clean power to use them, Varadarajan said. Developers will probably want to “overbuild” the amount of dedicated solar, wind, and batteries supplying data centers, so they can rely on those resources during more hours of the year. That means the renewables will often generate more than the data center needs at a particular moment, but in the power couple arrangement that extra power wouldn’t go to waste — it’d flow to the grid using the peaker plant’s oft-idle grid connection.

Importantly, from the perspective of a utility or grid operator, this setup is potentially far less disruptive than adding a big new load or trying to interconnect a brand-new source of generation, Varadarajan said. Many U.S. grid operators already have rules to allow sites that have grid connections to add different types of generation capacity or to use a power plant’s existing capacity more frequently.

And because the data centers will have all the power they need behind the interconnection point, power couples won’t have to enter the complicated technical and regulatory realm of projects that both inject and draw power from the grid — a status that can be a significant hangup for battery and “hybrid” battery-solar or battery-wind projects in some regions.

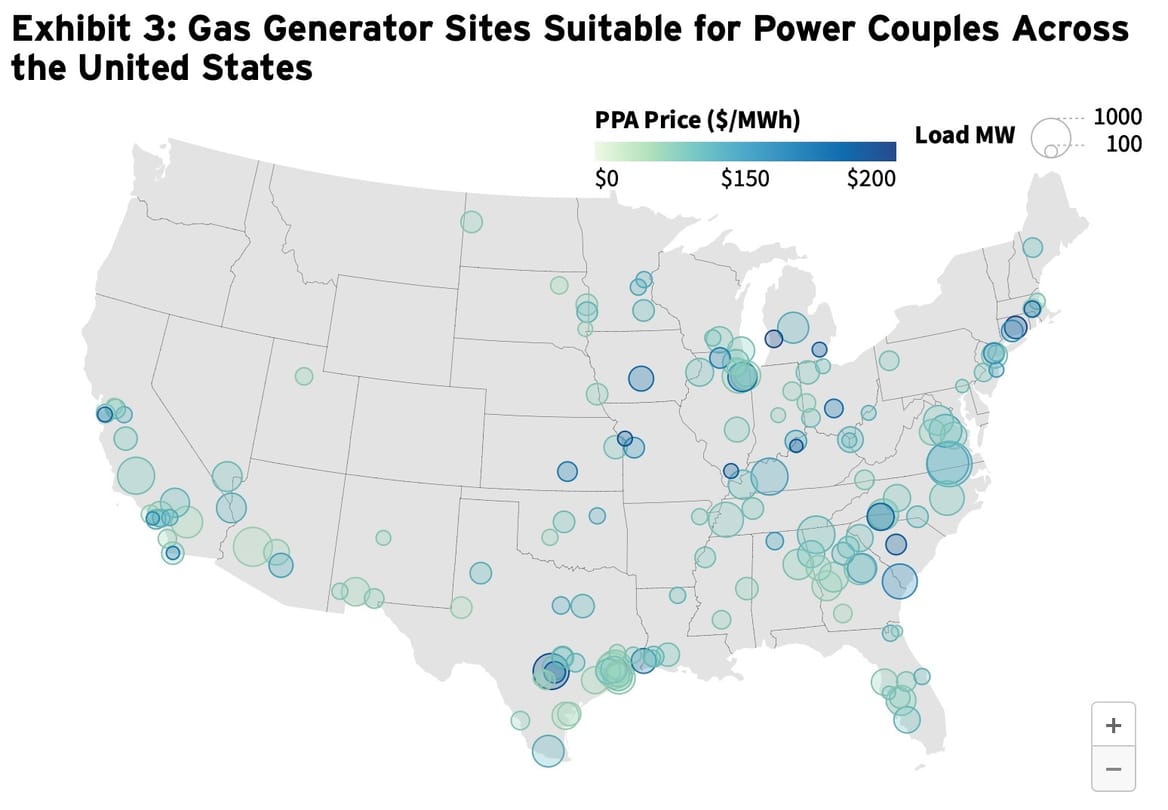

RMI mapped the lower 48 states for suitable power-couple sites, looking for peaker plants with enough available land within a 10-kilometer radius to be able to build solar power that can cover at least 60% of an accompanying data center’s annual electricity needs. But the sites identified in its analysis could add significantly more clean power than that — about 88% of the modeled data centers’ annual power consumption on average.