When the team at Second Harvest Food Bank of Northwest North Carolina first started planning construction of a new headquarters in Winston-Salem in 2019, they seriously considered solar panels.

“Food banking at its core has always been about sustainability,” said Beth Bealle, Second Harvest’s director of philanthropy, stewardship, and engagement. The organization rescues food that would have ended up in landfills to feed those in need, and Bealle and her colleagues wanted to push the sustainability concept “in other aspects of our work — like our facility.”

But at the time, they were advised that a rooftop array would be too expensive. Second Harvest shelved the idea and moved into its gleaming new 140,000-square-foot building in a former R.J. Reynolds Tobacco industrial park.

“Fast forward to the Piedmont Environmental Alliance Earth Day Fair of April 2023,” Bealle said. That’s where she met the alliance’s new green jobs program manager, Will Eley, who asked, “Did y’all know about the Inflation Reduction Act?”

Eley and Bealle “hit it off fabulously,” she said. Together, they took the food bank’s solar plan off the shelf and worked through the details of complying with the federal law’s clean energy incentives. Two years later, on Earth Day 2025, Second Harvest and the alliance flipped the switch on a 1-megawatt array, one of the largest rooftop solar projects in the state.

Assuming promised refunds from the federal government materialize, the project is expected to save Second Harvest $143,000 each year, funds the group says will be reinvested directly into programs that provide food, nutrition education, and workforce development across 18 counties of Northwest North Carolina.

But with the tax rebates now on the chopping block in Congress, other organizations considering new facilities may not have the chance to follow Second Harvest’s footsteps.

“We’ve already talked to several food banks who are in that process about our project, because they’re interested in putting solar on the rooftops of their new buildings,” Bealle said. “And that’s not going to be within reach for some people if these tax credits aren’t available.”

The federal government has long offered tax credits to incentivize renewable energy projects, from solar farms to rooftop arrays. But before the Inflation Reduction Act, those enticements were of little use to food banks and other entities that don’t pay an income tax.

The 2022 landmark climate law allowed organizations like Second Harvest to access the 30% tax credit on their solar investment by essentially transforming it to a rebate.

“The process by which they were able to fully monetize the tax credits was quite the game changer,” Eley said.

In North Carolina, the provision known as “direct pay” serves as a vital sequel to an expired rebate program from utility Duke Energy, which helped dozens of houses of worship and other nonprofits go solar during its five years of existence.

“Duke Energy had the nonprofit solar rebate, and that was a tremendous tool that was very helpful,” said Laura Combs, a one-time solar salesperson who worked with tax-exempt groups around the state to access the cash back from the utility. “When the direct payment came into play,” she said, “that took up that slack.”

The federal climate law also offers other inducements. It provides a 10% bonus to tax credits for projects deployed in government-defined “energy communities,” including those on former industrial sites or brownfields. At least another 10% is available for clean-electricity projects that are located in or benefit low-income communities.

As an organization that serves food-insecure households and that is headquartered in a poor census tract on a brownfield, Second Harvest qualified for both of these extra incentives.

“We really maximized the clean-energy layer cake,” Eley said.

Altogether, the tax credits cut the $1.5 million price tag for the solar rooftop installation in half, Eley said. While the food bank had to pay the full amount up front and won’t recoup those savings until it files its tax return for the year, the extra incentives mean the 1,702 solar panels will pay for themselves more quickly in the form of lower energy bills.

Second Harvest and Piedmont Environmental Alliance hoped the project would serve as a beacon to other nonprofits looking to go solar. And in and around Winston-Salem, that’s starting to come true, Eley says.

“It’s opened up several doors there,” he said, mentioning that a local credit union and groups like Goodwill have expressed interest in installing panels. “We’re presently working with six faith communities that are navigating [direct pay] and going through their feasibility and contracting processes for solar specifically.”

That tracks with a nationwide trend of houses of worship going solar thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act.

There’s also been an uptick in nonprofit installations statewide, according to data compiled by the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association.

The association doesn’t monitor whether institutions access the direct-pay feature, and some recent arrays may be holdovers from the Duke rebate program, which ended in 2022. But the numbers are striking nonetheless: Since 2011, almost 150 houses of worship, local governments, and other entities that don’t pay taxes have erected solar arrays, nearly all on rooftops. Sixty-three, or 42%, did so in 2023 and 2024.

Now, Eley said, the groups he’s working with are especially motivated to act quickly.

“The idea of going solar has been something they have tossed around for a number of years,” he said. “We’re certainly reiterating to them if you’re going to make that investment, do so now.”

That’s because the massive budget bill passed last month by the House — dubbed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act in an homage to President Donald Trump — would make tax credits for solar and other renewable energy projects nearly unusable. The Senate is now considering whether to pass the measure as is or to make changes.

As the legislation stands now, projects would have to begin construction within 60 days of the bill’s passage to access the 30% tax credit. That’s an easier feat for a rooftop installation than a larger, ground-mounted affair, but still incredibly difficult for nonprofits, religious institutions, or local governments that tend to have lengthy decision-making processes and aren’t already planning to go solar.

Even more unworkable is a provision that requires documentation that no component of a project, no matter how small, is linked to a“foreign entity of concern” such as China.

While House lawmakers voted to make the underlying 30% tax credit virtually useless, they didn’t explicitly target the three related adjustments that helped enable the Second Harvest project: direct pay, the low-income community benefit, and the brownfield benefit.

“These cross-cutting provisions are part of the tax credit structure, but they are their own mechanisms,” said Rachel McCleery, the former senior adviser at the U.S. Department of the Treasury who led stakeholder engagement for the climate law’s implementation.

The survival of direct pay in the House measure stands in contrast to the elimination of its twin in the private sector, transferability, which allows smaller energy companies better access to incentives.

But direct pay means little if the baseline 30% tax credit is still hamstrung by the 60-day start-work requirement and the foreign-entity provision.

“This is backdoor repeal of the IRA,” said McCleery, who now advises clients on defending clean energy tax credits, “and it’s backdoor repeal of direct pay — because you can’t use direct pay if you don’t have an underlying tax credit.”

The same applies to the bonus incentives for low-income and brownfield communities. “These cross-cutting mechanisms can still be used,” McCleery said, “but if the underlying credit is moot, that essentially repeals the mechanisms.”

On the flipside, if the Senate restores the viability of the underlying 30% tax credit in its version of the bill, the mechanisms that aid nonprofits like food banks and houses of worship will also be accessible.

But advocates say that remains a big “if.” And there are other challenges: Slashes to the Internal Revenue Service workforce could delay payments to Second Harvest and others. And the group is bracing for the impact of the other budget cuts in the House bill as written, such as to food assistance and Medicaid.

“It’s just going to put pressure on people who are already under-resourced,” Bealle said. “And that has a ripple effect to every organization that supports under-resourced people, including us.”

Combs, the former solar sales professional who also volunteers with climate advocacy group North Carolina Interfaith Power and Light, called it a “tragic snowball.” She then brought up U.S. Sen. Thom Tillis, the North Carolina Republican who has consistently voiced disapproval of a full-scale repeal of the tax credits.

“Thank goodness Sen. Tillis has spoken out and been a leader on the importance of the Inflation Reduction Act incentives,” Combs said. “I am anxious to see how this plays out in the Senate.”

A plan to build a wood-burning power plant in a Massachusetts city once dubbed the asthma capital of the country could be springing back to life years after state and local officials struck it down — and opponents are ready to renew their fight against what many call a “zombie project.”

Palmer Renewable Energy, the developer of the project in the city of Springfield, recently won a pair of legal victories reversing previous decisions to revoke key permits. At the same time, a little-known provision buried in the state’s 2021 climate law could pave the way for the project to improve its financials by selling renewable energy credits.

Local residents, community leaders, and environmental advocates are gearing up for another round of resistance by appealing the recent court rulings and pushing legislation to block the developer’s financial path forward.

“It’s really urgent,” said Laura Haight, U.S. policy director for the Partnership for Policy Integrity, a nonprofit that advocates against burning wood for power generation. “This is about making sure Palmer doesn’t rise again. There is no benefit — there’s only downside for the community.”

Palmer first proposed the plant in 2008, pitching it as a sustainable way to generate electricity by burning the woody waste left behind when utilities trim vegetation along power lines. The Springfield City Council issued initial approvals with little fanfare or public attention. Not long after, however, local residents and advocates realized what had happened and began to mobilize against the plan, kicking off years of debate and litigation.

Springfield, the third-largest city in Massachusetts, has long grappled with poor air quality and high asthma rates. The city sits at the intersection of two interstate highways, has a long industrial history, and was for many years home to a coal-burning power plant and neighbor to an oil and gas-fired plant. In 2018 and 2019, the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America dubbed the city the country’s asthma capital because of the prevalence of the disease and the high numbers of emergency room visits.

A wood-fired power plant may have an environmentally friendly ring to it. Proponents argue that the process is carbon-neutral because new trees can be grown to capture carbon, offsetting the emissions. However, researchers have found that promise is not the reality: The emissions created by burning wood have years to do climate damage before regrowth is adequate to absorb the added carbon dioxide. Burning woody biomass releases 50% more carbon dioxide than coal and three to four times as much as natural gas. Wood-burning facilities also emit other air pollutants and particulate matter that can cause or aggravate respiratory conditions.

Still, power plants that burn wood have often been propped up as valuable, sustainable resources. In the United Kingdom, the country’s largest single emitter is a wood-fired power station that, as of 2022, released more than 12 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. In European Union countries, the production of wood pellets to fuel power plants is big business, despite the objections of scientists and climate advocates.

In Springfield, a new power plant that would burn more than 1.2 million pounds of wood a day was not — and is not — an acceptable option, said many angry public health advocates, environmental activists, community leaders, and average citizens.

“It was a bad idea then, and it is still a bad idea,” said Sarita Hudson, senior director of strategy and development at the Public Health Institute of Western Massachusetts. “The community is against it.”

In 2015, however, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of Palmer in one of the cases challenging its permits, a decision that seemed to clear the way for construction. Palmer, however, never started building. So, in the spring of 2021, the Springfield Zoning Board of Appeals, at the request of the city council, ruled the project’s permits invalid, and the state rescinded its environmental approval, citing this lack of progress.

Opponents celebrated the demise of the project.

Palmer, however, was not ready to give up and appealed both of those decisions, arguing that statewide permit extensions implemented during the Great Recession and the Covid-19 pandemic meant it had more time to begin work. In January, the Massachusetts Superior Court agreed and ruled the project’s state air permit is still in effect. A few months later, the state Appeals Court also found Palmer’s building permits still valid, creating what many are calling a “Franken-permit.”

Both the state and Springfield City Council have appealed these rulings.

“There’s nothing stopping Palmer at this point from going back and applying for new building permits,” said Alexandra St. Pierre, director of communities and toxics for the Conservation Law Foundation, which is representing the city of Springfield in court. But the company would be unlikely to get approval this time around, she said, “and that’s why they’re pushing and pushing and pushing this issue.”

Permits are not the only potential hurdle: The plant still needs to make money, and observers doubt just selling power onto the grid would bring in enough revenue to turn a profit on an investment of that scale.

Earlier in the process, the administration of then-Gov. Charlie Baker (R) considered adding biomass facilities like Palmer to the list of renewable energy resources that qualify for the state’s renewable portfolio standard. Investor-owned utilities meet the standard by buying credits from operators of eligible renewable energy generation. Putting biomass on the list of renewable options would have allowed Palmer to make money selling such credits.

As public opposition mounted in 2021, however, Baker scrapped that proposal. But Palmer was already working on another plan.

While investor-owned utilities are required to meet the renewable portfolio standard, the state’s 41 municipally owned power companies are not. A 2021 climate law, however, created a new, separate standard for municipal utilities. The legislation does not include biomass on the initial list of eligible renewable resources, but does include a line adding biomass to the options as of 2026.

Palmer did not respond to requests for comment, so Canary Media cannot confirm when company leaders knew this addition was likely. But by late 2019, the developer had connected with Energy New England, a cooperative of municipal power companies, to promote the plant. In early 2020, eight municipal power companies signed contracts to buy 75% of the energy the Palmer plant was to produce.

“Which meant they were very, very close to having whatever financing they needed to get this project built,” Haight said.

As the project continued to stall and public sentiment against the plant grew, the municipal utilities all dropped their contracts in 2023. Observers, however, worry that some would sign back up if it helped them meet state requirements, either because they don’t know about the negative impacts of wood burning or because they are willing to overlook them.

Lawmakers in both the state House and Senate have introduced legislation to prevent biomass from joining the list of eligible resources next year. Gov. Maura Healey (D) also included the measure in the major energy bill she introduced last month, though supporters worry that legislation won’t advance quickly enough.

“There’s nothing subtle about this,” Haight said. “We have to close this loophole.”

A correction was made on June 17, 2025: This story originally misstated the amount of CO2 produced by the wood-burning power station that is the U.K.’s largest single emitter. As of 2022, the facility released over 12 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year, not per day.

A Chicago-area startup says its technology could shave emissions from the global metal industry by allowing companies to recycle grimy metal slivers and sludge left over from steel and aluminum production.

Steel and aluminum production account for about 7% of the world’s carbon emissions, according to the International Energy Agency. Decarbonizing the sector is expected to be a huge and costly undertaking, involving the overhaul of industrial processes more than a century old and the retrofitting of sprawling mills.

Sun Metalon aims to take smaller bites of the steel-decarbonization apple with an oven-sized box that promises to extract recyclable metal from a waste stream that would otherwise be sent to a landfill.

“You’ve got a company throwing something away, in some cases paying to throw it away because it’s contaminated with toxic materials. [Sun Metalon is] offering a way to create value from that,” said Nick Yavorsky, senior associate for the climate-aligned industries program at the clean energy nonprofit RMI, which is providing Sun Metalon 18 months of mentorship as part of its Third Derivative cleantech business accelerator.

On May 21, the company announced it had raised a total of $9.1 million in second-round startup funding from four investors, including Japanese steelmaking giant Nippon Steel.

The great majority of steel and aluminum in the U.S. is made from recycled metal, not raw ore. That’s fortunate, since creating this recycled metal emits much less carbon emissions than forging it from scratch. And that means increasing the amount of metal that can be recycled is one means of decarbonizing the industry.

“Some companies are looking at making steel in a new way, fully electrified,” as opposed to powered by coke, an energy-dense substance derived from coal, Yavorsky said. “Maybe there is not as much sexiness around folks reducing demand [for new steel], thinking about alternative materials. Yet these often are the fastest and most direct way to reduce emissions.”

Sun Metalon CEO and co-founder Kazuhiko Nishioka said he got the idea for the technology while working at Nippon Steel and studying for a PhD at Northwestern University near Chicago with Nippon’s support. In 2021, he and two colleagues at Nippon founded the company as they did DIY experiments to clean up tiny scraps too contaminated with oil or other substances to be recycled.

They received two patents on the heating technology in 2024. Sun Metalon’s units are modular “ovens” that can be placed on a factory or foundry floor; the metal waste fed into them is basically cleaned with intense heat and turned into “pucks” or “coins” that can be recycled in metal-making processes.

“We apply our heating, evaporate fluids, condense [impurities] back to liquid, and collect it,” explained Nishioka, noting the process involves reaching the boiling point of oil. The whole thing is powered by electricity, making it carbon-free if renewable energy is available.

“Sometimes scrap has a negative value, especially for sludges — no one can recycle it, so they have to pay for disposal,” he said. “We can bring it up to best or second best” in the value chain of recycled metal feedstock. “Then the profit can be shared among customers.”

The pucks can be sold to electric arc furnaces — essentially steel mills making recycled steel — or other metal recycling operations. Or they can be used onsite; for example, a car factory could channel metal waste from one part of the production line back into making new engine blocks.

“We are reducing new metal, and secondly, we are reducing logistics — nobody has to come pick it up” in diesel-burning trucks, said Nishioka.

Iulian Bobe joined Sun Metalon as chief strategy officer after co-founding a textile recycling company called Circ. He said steel and aluminum manufacturers are very eager to reduce their waste streams and their emissions; meanwhile, in Europe, decarbonization mandates drive demand.

“They’re really trying to get to a situation where they have zero landfill,” Bobe said. “They’re looking for solutions that can be implemented in the factories. You really don’t want to haul all that waste to another location. Our solution is very modular — we can put it on the site, achieving the circularity.”

Sun Metalon says it has received a total of $40 million from investors. Both Toyota Motor Co. and the construction equipment manufacturer Komatsu have purchased its equipment, tested it in their facilities, and promised to work with Sun Metalon to scale up the technology.

A 2024 press release from Komatsu explains that making the high-chromium cast-iron sealing rings used on undercarriages of its equipment produces a lot of polishing sludge — “a difficult-to-handle mixture of fine metal particles, oil, and water.”

Each year, Komatsu produces 150 tons of the sludge, which is hard to safely melt and recycle, according to the release — but Sun Metalon could change that.

“This endeavor not only promises significant resource conservation and waste treatment cost reductions but also aligns with broader decarbonization efforts in metal processing,” says the press release.

Toyota Motor Co. and Sun Metalon presented results of their tests at a May 2023 conference of the Japan Foundry Engineering Society, according to a Sun Metalon press release. (Nishioka declined to put Canary Media in contact with representatives of those companies, other investors, or potential customers.)

The Round A funding announced recently included Airbus Ventures, a Japanese bank, and an innovation fund, along with Nippon Steel, which is seeking to acquire U.S. Steel, including its Gary Works mill in Northwest Indiana. In recent weeks, President Donald Trump has expressed his support for an acquisition that would include decision-making power for the federal government — a sharp turn from promises he made on the campaign trail to block the move.

The Recycled Materials Association, a trade group that represents metal recycling, noted that over 70% of steel and 80% of aluminum in the U.S. is made from recycled material.

“Compared to the processing and transportation needed for mining, drilling, harvesting, or other methods of extracting natural resources for manufacturing, the use of recycled materials typically produces fewer greenhouse gas emissions,” Rachel Bookman, a spokesperson for the organization, said by email.

The trade association declined to comment specifically about Sun Metalon, which is one of its members.

Nishioka said the technology could be useful for “automotive and aerospace, construction machinery, any product using metal,” adding that he plans to pitch to steel mills and foundries in the Midwest and South.

“Any process melting metal can benefit,” he continued, “either companies that are melting metal or companies purchasing from those companies.”

Nishioka imagines that with more innovation, the modular technology could be used not only to prepare metal for recycling but to actually create metal products.

He’s also hopeful that new industrial processes could spur manufacturing in developing nations, an idea inspired by his time volunteering in Kenya as an undergraduate student.

“My original vision was to bring compact steelmaking processes into a couple different boxes,” he said. “We can bring those boxes wherever we want. It could be in Africa, or on Mars.”

Last week, the Trump administration canceled $3.7 billion in federal funding for two dozen green industrial projects that the Department of Energy claimed “failed to advance the energy needs of the American people, were not economically viable, and would not generate a positive return on investment of taxpayer dollars.”

More than a quarter of that spending would have gone to 11 projects designed to cut planet-warming pollution from generating the heat used in factories — one of the trickiest decarbonization challenges to solve.

“This is a really, really significant setback for clean heat in the U.S.,” said Brad Townsend, the vice president of policy and outreach at the think tank Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES).

The wide-ranging projects included installing industrial heat pumps at up to 10 plants where giant Kraft Heinz Co. produces its foodstuffs, building an electric boiler at one of plumbing-fixture manufacturer Kohler Co.’s Arizona factories, and adding a heat battery to Eastman Chemical Co.’s facility in Texas.

Distributed under the Industrial Demonstrations Program at the Energy Department’s now-embattled Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, the funding promised to bolster the manufacturing sector with a major investment in technologies meant to give American companies an edge in global markets.

Groups such as C2ES and the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy estimated the federal support would generate hundreds of thousands of jobs in both direct construction and operations and indirect hiring at real estate firms, restaurants, and retailers near the industrial sites. In addition, federal researchers expected to gather information through the projects that could be used broadly throughout U.S. industry to improve output and bring down energy costs.

“The data and lessons learned in de-risking this technology would then translate into follow-up investment in the private sector,” said Marcela Mulholland, a former official at the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations who now leads advocacy at the nonpartisan climate group Clean Tomorrow.

“If you were in a technology area covered by OCED, you needed public investment to scale,” she added. “Something in the proverbial ‘valley of death’ made it difficult for the private sector to advance the technology on its own.”

With the funding, U.S. industry had the chance to develop new approaches that could produce greener — and cheaper — materials, giving American manufacturers an edge over Asian or European rivals as corporate and national carbon-cutting policies put a premium on products made with less emissions. Absent that, Mulholland said, U.S. companies risk falling behind competitors who benefit from lower-cost labor and easily accessible components from nearby industrial clusters, like those in Vietnam, China, or Germany.

“It’s hard to overstate the scale of the loss,” Mulholland said.

Already, a handful of companies are considering shifting production overseas in the wake of the funding cuts, according to two sources who have directly spoken to leaders of firms that lost federal funding. The sources were granted anonymity because they are not authorized to speak publicly about the plans.

“When these projects don’t go forward, we’re going to see challenges for the companies from a profitability perspective and from a global competitiveness perspective,” said Richard Hart, industry director at the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. “What happens then is other countries and other companies will step in to meet those demands.”

In the long term, he added, the cuts erode the value of a federal contract.

“When the U.S. government signs a contract with you, it’s reasonable to assume that that contract is gold and that you can use that contract to make plans as a company that … you can explain to investors, to employees, and to the full group of stakeholders around your facilities,” Hart said. “The loss of trust that comes from canceling those contracts is likely to be pervasive. That’s very sad.”

Part of the problem is that the contracts were cost-share agreements, which traditionally give the federal government the right to exit the deals without any legal penalty. In theory, OCED could have structured the federal contracts differently through a category known plainly as “Other Transactions.” The Department of Commerce, for example, issued money from the CHIPS and Science Act to semiconductor companies through such “other transactions” that lack the same off-ramps for the government.

But the Commerce Department did so under the advice of a legal memo from its general counsel. By contrast, the Energy Department “is way, way behind” on adopting alternative contract structures when disbursing money, according to a former OCED official who spoke on condition of anonymity.

As a result, the agency stuck to the financing mechanisms with which it was familiar — such as cost-share agreements.

Internally, the Trump administration said the cuts were justified in part because the companies involved were well funded and could manage the investments themselves, the official said.

“But I don’t think that’s the case. They need a government incentive to make the technological changes they were trying to do,” the former OCED official said.

“I would bet less than half of them keep going by themselves,” the official added. “It’s a big blow.”

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the week” column.

California is throwing away a lot of solar power.

The state curtailed 3,400 gigawatt-hours of utility-scale renewable electricity last year, 93% of which was produced by solar panels, per a U.S. Energy Information Administration analysis of data from California’s grid operator.

When the sun shines bright and the breeze blows hard, solar panels and wind turbines often produce more power than the grid needs or can handle. In those moments, the grid operator will order power plant owners to reduce their output. That’s called curtailment, and it’s common in places like California that have lots of renewables.

It’s no surprise that California is having to curtail power as it adds more solar to the grid — but curtailments are rising faster in the state than renewable generation capacity is growing. Last year, curtailments jumped by 29% compared with 2023, while California added only about 12% more utility-scale solar capacity.

Curtailments are at their highest in California during the spring, when the sun is strong enough to generate a lot of solar power but mild weather keeps air-conditioning use, and thus electricity demand, in check.

With power demand rising around the country thanks in large part to the rapid rollout of AI data centers, and with California behind on climate goals, it’s important for the state to try and reduce curtailments and use more of the clean power it’s already capable of generating.

There are a few ways to do that. California can continue to push buildings, vehicles, and industrial operations to electrify, creating more demand to soak up what is now surplus solar. It can support the construction of interstate transmission lines that would allow it to export more power to states with less solar generation.

The state can also build lots and lots of batteries to store extra solar produced during the day for use in the evening. In fact, it’s already doing that. It has installed more utility-scale storage than any other state, and the sector has grown rapidly in recent years: California had a total of 13.2 GW of utility-scale storage online as of last month, far more than the nearly 8 GW it had at the end of 2023.

In order to stop wasting clean electricity, California will need to sustain that battery boom in the face of significant federal policy headwinds — and place some bets on other, more elusive solutions like transmission and long-duration energy storage.

The 79th Street corridor is one of the busiest thoroughfares on Chicago’s Southeast Side. But many of its adjacent side streets are poorly lit at night, posing hazards ranging from inconvenient to dangerous.

For instance, obscured house numbers can confuse both delivery drivers and emergency responders. And higher levels of crime have been correlated with poorly lit streets, making it feel unsafe for children to play outdoors after sunset or for pedestrians to walk alone in the dark.

“For those people who are going to work in the winter at five o’clock in the morning and it’s pitch black out there, yeah, they’re scared. They’re walking down the middle of the street,” said Sharon “Sy” Lewis, founder and executive director of Meadows Eastside Community Resource Organization, commonly referred to by its acronym of MECRO.

But block by block, things are changing, in no small part due to Light Up the Night, administered by MECRO in collaboration with the energy-efficiency program of Chicago utility ComEd. The initiative aims to solve the problem of dark streets by outfitting the front and back of homes with energy-efficient lights that automatically turn on at night and off during the day.

Light Up the Night was launched in 2019 as a pilot program in the South Shore community of the city’s South Side with an initial goal of providing Energy Star-certified LED light bulbs for up to 300 residences.

The program had to pause during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, but eventually, Light Up the Night was able to achieve that goal and then some. Lewis said it has served more than 500 homes so far, and she is pursuing funding to expand.

MECRO staff or volunteers install the bulbs into existing outlets at no charge to residents. Lewis said this proactive approach yields better results than just distributing packages of light bulbs and other energy-saving devices that may or may not get used.

For Lewis, the installation process provides an opening to talk to residents about other energy-efficient measures, like weatherization or purchasing new appliances. The upgrades, often eligible for rebates to offset the cost, can dramatically reduce utility bills. This is particularly impactful in communities like those surrounding the 79th Street corridor, in which many residents spend a big portion of their income on energy bills, largely due to predominantly older and often poorly insulated housing stock.

“Light Up the Night is not just a gateway to safety, it’s a gateway to energy savings. And it starts with the little things. And because we installed it, instead of sending them an ‘energy box,’ then we know that it’s working. When you drive down that street, you know that it’s working, you see that impact,” Lewis said.

A minimum of 75% participation is required per block, and each homeowner or renter must provide consent before installation can begin, Lewis said.

“If the average block has 36 homes on it, if we get 15 on each side, at minimum, we have really created an impact for the block,” Lewis said. “So now you have the whole community lighting up at once [at dusk], and then they all go off in the morning.”

A legacy of segregation and disinvestment has left residents of predominantly Black communities like the Southeast Side with a strong distrust of outsiders. As a lifelong resident and visible activist, Lewis has an advantage when it comes to engaging with residents, but obtaining initial buy-in around South Shore was still a challenge.

“Getting people to sign up, that was a problem because we can’t not have data on where we are leaving the lights. … [But] people didn’t want to provide their information,” Lewis said.

To get the program up and running, Lewis worked with neighborhood block clubs to overcome apprehension and to identify particular streets in the South Shore community that would benefit the most from the new lights. She also worked with other community organizations, especially those focused on violence prevention.

It was easier to start up the program in Austin, a neighborhood on the city’s West Side, where, also in 2019, Lewis collaborated with Steve Robinson, executive director of the Northwest Austin Council, with whom she had worked previously on a number of initiatives. Chicago police officers assigned to that community were also enthusiastic about the program, and helped Lewis identify blocks where adding lights would be especially impactful, she said.

“[Robinson] invited me over there. It was a whole change. It was a sea change. It was amazing. [The police] were excited about it. They were looking forward to the change we were doing,” Lewis said.

Wherever it has been implemented, this small-scale program has had an outsized positive impact, Lewis said. Additional lighting on front porches and entryways also enhances safety for visitors to the community, including service providers like mail carriers, delivery people, and rideshare drivers. Likewise, floodlights installed at the rear of a home or apartment building add to the ambient lighting in often dark alleyways, which results in fewer garage break-ins and instances of illegal dumping of garbage, Lewis said.

MECRO does much more than install lights. The organization also helps guide new and existing small business owners, conducting educational seminars and offering technical assistance. And it provides residents with referrals for energy-efficiency improvements and other sustainability-related resources they might not otherwise know about.

But Light Up the Night remains part of the organization’s core mission.

While illuminating areas that used to be dark is the program’s first objective, once the new bulbs have replaced older, less-efficient lights, the lower utility bills can be eye-opening for residents.

When people see those savings, “they start thinking, ‘Well, what if I get all energy-efficiency light bulbs? Hmm. Okay, now my bill has gone really down. What if I do the weatherization program? Now my bill is really down,’” Lewis said.

Massachusetts-based Boston Metal is on the verge of earning its first revenue as it continues honing a novel steelmaking process so clean it can vent emissions into a parking lot the company shares with a day care center.

“It just proves how different the future of steel can be,” said the firm’s senior vice president for business development, Adam Rauwerdink.

The technique, which was developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is now being scaled up for commercialization, uses electricity to remove contaminants from iron ore, producing a small fraction of the emissions generated by traditional fossil fuel–fired blast furnaces. Indeed, the technology releases no carbon dioxide — just oxygen — and the only greenhouse gas emissions are those associated with the electricity used to power the system.

Promoting green steel was a major element of former President Joe Biden’s economic and environmental agenda. However, the Trump administration’s desire to boost fossil fuels has already undermined these efforts and left the future of the sector in question.

Against that backdrop, Boston Metal, with its carefully calibrated business plan and lack of dependence on increasingly unreliable federal funding, seems to have unusually bright prospects.

The company was founded in 2013 to take on the challenge of reducing the tremendous amounts of greenhouse gases released by the steel industry, a sector responsible for 7% to 9% of global emissions. Boston Metal has since received some $400 million in investments from a range of backers including global steel giant ArcelorMittal, the venture-capital arm of oil company Saudi Aramco, global investment manager M&G Investments, the World Bank’s International Finance Corp., and major climatetech funds such as Breakthrough Energy Ventures and Microsoft’s Climate Innovation Fund.

The possible payoff is significant: Demand for low-emissions steel is expected to increase by at least 6.7 million tons by 2030, though production of green steel is still very limited globally, said Kaitlyn Ramirez, senior associate with energy transition think tank RMI.

“The demand for green steel is there,” Ramirez said. “We’re seeing the momentum … even when there are challenges on the supply side that need to be resolved.”

The task of greening steel production is daunting. Globally, nearly 1.9 billion metric tons of steel are produced each year, and on average, each ton of steel is responsible for 2 tons of carbon dioxide emissions.

Roughly 90% of the emissions associated with steelmaking are generated by refining iron to use as a base material, Rauwerdink said. And that step has historically depended on burning a fuel — usually coal — to create the high temperatures at which iron ore can be melted and impurities removed. Seven such coal-fired plants remain in operation in the United States, contributing to high pollution levels in the cities where they are located.

Another process, known as direct reduction of iron, or DRI, burns natural gas to remove contaminants from iron ore. DRI systems can also be configured to burn hydrogen, though the current supply of green hydrogen — hydrogen created using renewable energy — is too scant and too expensive to be a reliable source of low-emissions fuel right now, Ramirez said. Still, she noted that hydrogen-fueled DRI is currently the most promising emerging alternative to traditional, emissions-intensive steel production.

“They can start using more hydrogen as it becomes available,” she said.

Boston Metal sidesteps that complication by refining iron through a process called molten oxide electrolysis. Iron ore is poured into a brick-lined chamber, where it dissolves in an electrolyte solution. An electric current runs through the liquid, melting the ore. Contaminants in the ore — like alumina, silica, and calcia — are left behind in the solution, while the molten purified metal settles to the bottom of the chamber.

When enough iron has accumulated, the chamber is tapped, in a sort of fiery, industrial analog to tapping a maple tree for sap. A meter-long bit drills into the cell, allowing the molten iron to flow out. Then the hole is plugged with a ceramic clay until the next tapping.

Though the equipment runs constantly at a temperature of about 1,600 degrees Celsius, the air just a few feet away remains cool. The entire production floor is light and clean, and the only noise is a low buzz from the machines — a far cry from the traditional sweltering, clamorous steel mills.

The electricity powering the process runs from an anode at the top of the chamber to the molten metal, which acts as a cathode. The anode is one of Boston Metal’s major technological innovations. For the equipment to produce significant quantities of molten iron, the anode must be made of a material that can resist corrosion in the oxygen-rich environment. MIT researchers developed an alloy that can do just that.

The anode “can run for a month and it comes out the same shape and size,” Rauwerdink said, noting that the company relies on laser imaging to precisely find and measure even the most miniscule changes.

The first trial runs in the MIT lab used an anode about the size of a marble and produced a roughly 1-gram nugget of purified iron. At Boston Metal’s 38,000-square-foot facility in a Boston suburb, five of these small-scale systems are still in operation, allowing technicians, over the course of several hours, to see how variations in the electrical current or the electrolyte composition affect the process.

Several midsize systems also run in the facility as does one full-scale cell that can produce roughly a ton of purified iron per month using 10 anodes, each roughly the size and shape of half a basketball. When expanded to production scale, each cell can be fitted with more anodes, and each operation can have multiple cells running. Rauwerdink estimates that commercial producers will be able to put out multiple tons every day.

As Boston Metal continues to refine its system, it is also trying to work its way toward profitability. To get there, company leaders have decided on a strategy that, perhaps unexpectedly, puts steel on the back burner for the moment.

The key is niobium, a metal that is valuable as an alloying element in steel production and that can be extracted from other materials using molten oxide electrolysis. Niobium sells for about $82 per kilogram (about $74,000 per ton) right now, according to the Shanghai Metals Market, while steel goes for roughly $900 per ton. Boston Metal plans to focus on extracting and selling the metal for now, to start bringing in money while continuing to finesse its method for producing green steel.

In 2023, the company began building a facility in Brazil to extract niobium from mining waste and industrial slag. The first cell in the operation should come online this month, and revenue is expected to start flowing later this year.

“That’s a big milestone for us,” Rauwerdink said.

This graduated approach gives the company some stability at a time when the future of green steel in the U.S. is anything but certain.

Last year, the Biden administration awarded $500 million each to two projects aiming to make low-emissions steel using hydrogen for DRI. However, one recipient, Cleveland-Cliffs, has announced that, in light of the Trump administration’s preferences, it will instead be relying on “more economical fossil fuels” and also prolonging the life of an existing coal-burning blast furnace. Further, as Japan’s Nippon Steel looks to acquire U.S. Steel, Trump has touted the possibility of keeping the operation’s coal-burning blast furnaces up and running for another 10 years. The Trump administration has also halted or rolled back much of the funding Biden had dedicated to green steel development.

Boston Metal, however, is somewhat insulated from these headwinds. While Trump’s funding moves have created economic uncertainty, the company is not directly supported by any federal grants, though it has received some federal support in the past. The company is waiting to hear the fate of a $50 million grant related to chromium production, but the outcome will have no effect on its plans to commercialize the molten oxide electrification process. And because the system doesn’t use any fossil fuels, the political battles over coal and natural gas have little relevance.

Boston Metal plans to build a demonstration plant for steel production by 2028 — it’s still looking for the right site — then take the system to market. The company intends to license the technology to steel-making operations, rather than owning and operating facilities itself, and is already exploring opportunities in the United States, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, Rauwerdink said.

Producers using Boston Metal’s technology are likely to seek out locations with a clean, low-priced electric supply to maximize the economic and environmental advantages, he said.

Boston Metal’s technology and that of other companies exploring the use of electricity hold a lot of promise, but plenty of questions and hurdles remain, Ramirez said.

“They’re very exciting, and they definitely have a role to play,” she said. “The questions are timeline and scale.

A correction was made on June 5, 2025: This story originally misidentified Boston Metal’s initial source of revenue. It will be from the sale of niobium, not from steelmaking. The story also originally misstated the material from which Boston Metal will extract niobium. The firm will extract niobium from mining waste and industrial slag, not iron ore.

A pesky question has long stalled efforts to expand U.S. power grids in the face of growing demand and surging renewable energy: Who should pay for the upgrades?

An under-the-radar breakthrough in Massachusetts may finally provide a template for answering that question.

Over the past year or so, the state’s largest utilities and regulators have approved plans for dividing grid costs between customers and the companies that build solar arrays.

It’s been a long time coming. The plans in question have gone through numerous iterations since utilities, regulators, and solar developers started working on them about six years ago, making progress hard to track. And the name they settled on — “Capital Investment Projects,” or CIPs — isn’t exactly an attention grabber.

But behind the staid name lies a significant advance for a state striving to fairly allocate the costs of shifting to clean energy, said Kate Tohme, director of interconnection policy at Massachusetts-based community solar developer New Leaf Energy. In fact, advocates working on similar efforts in states from New York to California are “all trying to use the Massachusetts framework as a model,” she said.

The roughly $334 million in CIP grid projects from utilities Eversource and National Grid that have been approved or are being considered by regulators are doing something rare in the world of regulated utilities. Instead of forcing distributed solar and battery projects to pay up-front for grid improvements that allow them to connect to the utility system, the CIPs spread those costs onto customers’ future utility bills. Under the old system, clean energy projects regularly died on the vine because up-front grid costs were prohibitively high.

That doesn’t mean developers are getting a free ride, however. They’ll still have to pay a portion of those costs back as they’re connected to the grid, reducing the burden on customers over time. And every project in question had to prove to regulators that the grid improvements at large also deliver customer benefits, whether through improved grid reliability, enabling access to cheaper community solar power, or both.

Massachusetts can’t avoid these kinds of grid investments if it’s to meet its clean energy and electrification goals, according to Tohme, a former official at the state Department of Public Utilities who was directly involved in some of the earliest CIP work. The state has committed to cutting emissions 50% below 1990 levels by 2030, which will require building lots of renewable energy and electrifying vehicles and home heating.

“In the short term, it’s going to increase our costs,” Tohme said. But “once the grid is modernized and we get distributed energy interconnected, it’s going to drastically decrease our electricity costs” by replacing expensive fossil-fueled power with cheaper renewable energy and batteries.

The landmark plan emerged as a response to what might be seen as a clean-energy success story — Massachusetts had too much community solar trying to get onto an overly crowded grid.

The launch of the Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target program in 2018 had created lucrative incentives for community solar developers, spurring a rush of applications to connect to utility distribution grids. As available capacity was used up, the cost of upgrading those grids to accommodate more solar power started to rise.

“For a while, the cost to interconnect was tens of thousands of dollars, something a project could absorb,” said Mike Porcaro, director of innovative grid solutions at National Grid, one of the state’s largest utilities. “But eventually the modifications grew so large — hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars — that it was hard for projects to move forward.”

National Grid was encountering the same kind of interconnection backlog and upgrade cost challenges that have tied up utility-scale solar and wind projects on high-voltage transmission grids across the country. The main difference is that community solar projects connect to lower-voltage grids that carry power from big substations to end customers. Similar backlogs have dogged other states with lots of community solar, including Minnesota and New York.

One of the best-established ways to relieve interconnection stresses is for utilities and grid operators to stop painstakingly studying each project one at a time and batch them instead. Such “group” or “cluster” studies of multiple projects seeking interconnection in a particular region allow utilities to conduct a speedier and more holistic assessment of the impacts they’ll cause and upgrades that will solve them.

It also allows grid-upgrade costs to be shared among the projects in the cluster, rather than foisting them on whichever project engineers determined would push that part of the grid over its existing capacity limit, thus triggering an upgrade, Porcaro said.

But the approach has its limits. “You’re still sharing the costs among that group,” he said — and forcing projects to pay even a portion of those costs up front can still make them too expensive to move forward.

To deal with that disconnect, the Department of Public Utilities launched its “provisional system planning program,” the precursor to the CIPs, in 2021. The idea, Porcaro said, was to allow utilities to move faster on solving the fundamental problem for all of those community solar projects — a grid that wasn’t being built out quickly enough to match the exploding demand for capacity.

National Grid and other utilities already plan ahead to accommodate growing electricity demand from customers or to serve big new developments like housing subdivisions or factories, Porcaro noted. The goal of the provisional system planning approach was to find a way to similarly pay in advance for proactive grid investments to bring community solar projects online.

“The review and discovery to get these CIPs approved was no small feat,” Porcaro said. “It wasn’t a quick decision.”

In late 2022, the Department of Public Utilities approved its first test case for CIPs — a cluster of projects put forward by utility Eversource, known as the “Marion-Fairhaven Study Group” after two of the Southeastern Massachusetts towns in the area being considered for upgrades.

Eversource estimated at the time that it would cost about $116 million in distribution grid upgrades to enable roughly 140 megawatts of community solar to connect to the grid. To avoid the chicken-and-egg problem of requiring projects to pay up front for the upgrades — something they couldn’t afford to do — Eversource proposed charging them about $370 per kilowatt of solar they connected once the grid work was done.

The risk of this approach is that some of the projects involved in the group study would end up dropping out, leaving customers on the hook for their unpaid share, Lavelle Freeman, Eversource’s vice president of distribution system planning, told Canary Media in a 2023 interview. That put the burden on Eversource to plan a grid upgrade that didn’t just make room for the solar projects but benefited customers as well.

Fortunately, the same kinds of upgrades that expand capacity for community solar also improve customer reliability and provide headroom for growing electrical loads.

“We’re also improving the substations, adding new capacity, adding new transformers and feeders, making the system more robust,” Freeman said. “We developed a very rigorous algorithm to calculate the reliability benefits,” which ended up showing a roughly 50-50 split in the benefits between customers and solar developers. “That went a long way toward convincing regulators that the cost-allocation principle would work.”

To be clear, there are significant risks to committing utility customers’ money to building out grid infrastructure to serve the needs of community solar projects. In Massachusetts, the state Attorney General’s Office is tasked with protecting utility customers’ interests in regulatory proceedings like these.

A senior official at the Attorney General’s Office who was involved with the CIP process told Canary Media that the office “took serious issue” with how Eversource first proposed splitting grid-upgrade costs. “Not only were ratepayers paying more than they should have, it created a lot of risk for ratepayers,” said the person, who was granted anonymity to discuss matters outside the official regulatory process.

On the other hand, the official said, “being able to have more homegrown generation is going to be important for Massachusetts. It is a cost risk. But how do we minimize those cost risks to ratepayers, and maximize those benefits to ratepayers, as we bring this solar online?”

These concerns from the Attorney General’s Office pushed the finalized version of CIP to shift more of the cost of new grid investments onto community solar projects as opposed to utility customers. That’s not ideal from the perspective of solar developers, obviously, but it’s far better than being stuck with the unaffordable upgrade costs they faced before.

Having a known per-kilowatt cost locked in well in advance is also helpful, said Mike Judge, currently undersecretary of energy for the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, who spoke to Canary Media in 2023 when he was vice president of policy for the trade group Coalition for Community Solar Access.

Developers often need to secure interconnection rights before they can secure the financing and start signing up subscribers that allow them to move forward with projects, he said.

“There’s so much value for a developer to know I’m going to pay $370 a kilowatt to connect,” Judge said. “You’re not waiting a year, year and a half for a utility to come back with study results to say, it’s $5 million — and you have to cancel your project.”

The model that Eversource established for the Marion-Fairhaven project is largely mirrored in the 10 other CIPs that it and National Grid have submitted to regulators. All told, Eversource has identified six groups with more than 250 MW of community solar or battery storage capacity. Porcaro said that National Grid has five CIPs that will enable about 300 MW of new projects — “that’s huge.”

Massachusetts isn’t the only state working on policies that aim to spur grid expansion while keeping customers’ power costs in check, Tohme said. Similar efforts are now underway in states including California, Colorado, Maryland, Minnesota, and New York.

But to Tohme’s knowledge, no other state has accomplished what Massachusetts has with its CIP structure. New York is closest, she said, with a cost-sharing framework that allows community solar developers to split up the costs of necessary upgrades rather than bearing them alone. But that still doesn’t include the same “build in advance, pay later” structure that the CIPs have, she said.

At the same time, Tohme pointed out, the CIPs remain a response to a problem that’s been hounding the state for years now: projects stuck behind an inadequately upgraded grid. The next logical step is to figure out where grid upgrades should be made before that kind of situation happens again.

That’s one of the goals laid out for the state’s three major investor-owned utilities under a sprawling grid-modernization mandate created as part of a major energy and climate law passed in 2022. It’s called the Electric Sector Modernization Plans process, and the Department of Public Utilities is now reviewing the proposals submitted by utilities last year to determine next steps, Porcaro said.

CIPs are a part of that broader plan, he said. But the modernization plans are “going above that and saying, ‘plan for everything’ — for everyone having an EV, and electrifying their homes, and specific goals for how much energy storage we need. It’s a tall order.”

Given how long it took to figure out CIPs, clean energy developers have reason to worry that this even more sweeping and complicated planning task could take even longer. Clean-energy industry group Advanced Energy United has urged state regulators to keep doing CIPs while it undertakes this broader new effort.

Porcaro highlighted other work that can help get more clean energy connected even before the grid gets built out. He pointed to National Grid’s Active Resource Integration pilot, launching this year, which is looking at ways community solar and battery projects can connect to grids that can safely absorb their power output during all but a handful of hours of the year. If those solar farms can curtail their output during those hours, they could connect years ahead of utility grid upgrades.

These kinds of “flexible interconnection” structures, as they’re generally known, could help “get us through now to when the full system could be built, or to get through certain areas where you don’t need a full buildout,” Porcaro said.

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking on building out a grid that can support Massachusetts’ clean energy and electrification ambitions. Later this year, the Department of Public Utilities is expected to issue its ground rules on how utilities should start to calculate the fair sharing of costs between their customers and the community solar and battery projects trying to connect to their grids under the Electric Sector Modernization Plans, Tohme said.

Once that’s done, utilities and other stakeholder groups will bring cost-sharing proposals to the regulator and start to hash them out, she said. ”So we have a long way to go before we have proactive proposals.”

But just because it’s going to be hard doesn’t mean it isn’t worth doing, she said. “We have to modernize our grid. Right now we’re doing it anyway — we’re just reacting. We’re just doing it non-strategically. And that’s just as expensive,” Tohme said — if not more so.

2025 is a pivotal moment for climate action. Countries are submitting new climate commitments, otherwise known as "Nationally Determined Contributions" or "NDCs," that will shape the trajectory of global climate progress through 2035.

These new commitments will show how boldly countries plan to cut their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, transform their economies, and strengthen resilience to growing threats like extreme weather, wildfires and floods. Collectively, they will determine how far the world goes toward limiting global temperature rise and avoiding the worst climate impacts.

A few countries, such as the U.S., U.K. and Brazil, have already put forward new climate plans — and their ambition is a mixed bag. But it's still early: Many more countries, including major emitters like the EU and China, have yet to reveal their NDCs and are expected to do so in the coming months.

We analyzed the initial submissions for a snapshot of how countries' climate plans are shaping up so far and what they reveal about the road ahead.

A decade ago, the world was headed toward 3.7-4.8 degrees C (6.7-8.6 degrees F) of warming by 2100, threatening catastrophic weather, devastating biodiversity loss and widespread economic disruptions. In response, the Paris Agreement set a global goal: limit temperature rise to well below 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) and strive to limit it to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F), thresholds scientists say can significantly lessen climate hazards. Though some impacts are inevitable — with extreme heat, storms, fires and floods already worsening — lower levels of warming dramatically reduce their severity. Every fraction of a degree matters.

To keep the Paris Agreement's temperature goals within reach, countries agreed to submit new NDCs every five years. These national plans detail how (and how much) each country will cut emissions, how they'll adapt to climate impacts like droughts and rising seas, and what support they'll need to deliver on those efforts.

Countries have gone through two rounds of NDCs so far, in 2015 and 2020-2021, with their commitments extending through 2030.

While the latest NDCs cut emissions more deeply than those from 2015, they still fall short of the ambition needed to hold warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees C. If fully implemented (including measures that require international support), they could bring down projected warming to 2.6-2.8 degrees C (4.7-5 degrees F). And without stronger policies to meet countries' targets, the world could be heading for a far more dangerous 3.1 degrees C (5.6 degrees F) of warming by 2100.

Now the third round is underway, with countries expected to set climate targets through 2035.

These new NDCs are expected to reflect the outcomes of the 2023 Global Stocktake, which was the first comprehensive assessment of global climate progress under the Paris Agreement. In addition to bigger emissions cuts in line with holding warming to 1.5 degrees C, the Stocktake called on countries to act swiftly in areas that matter most for addressing the climate crisis — especially fossil fuels, renewables, transport and forests — and to do more to build resilience to climate impacts.

2025 NDCs are also an opportunity to align near-term climate action with longer-term goals. Over 100 countries have already pledged to reach net-zero emissions, most by around mid-century. Their new NDCs should chart a course toward achieving this.

Under the Paris Agreement's timeline, 2025 NDCs were technically due in February. As of late May, only a small proportion of countries had submitted them, covering around a quarter of global emissions.

These early movers include a diverse mix of developed and developing nations from different regions and economic backgrounds.

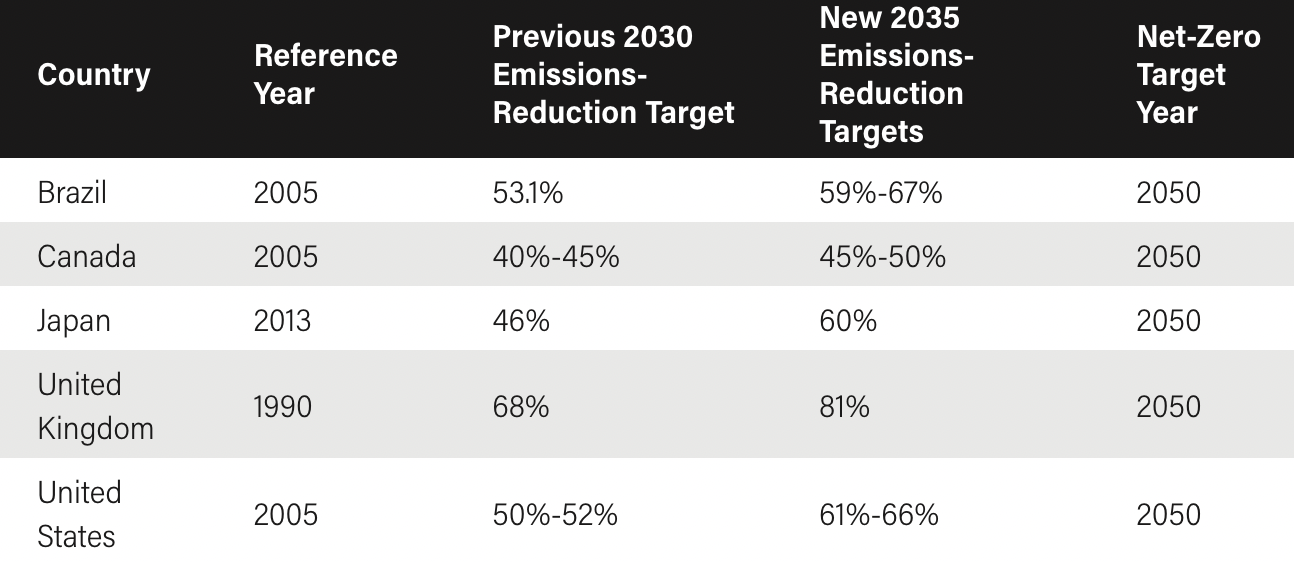

Among the G20 — the world's largest GHG emitters — only five countries submitted new NDCs so far: Canada, Brazil, Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom. (Since submitting its NDC, the U.S. announced its intention to withdraw from the Paris Agreement.)

Several smaller and highly climate-vulnerable countries have also stepped forward, including Ecuador and Uruguay in Latin America; Kenya, Zambia and Zimbabwe in Africa; and island states such as Singapore, the Marshall Islands and the Maldives.

That means close to 90% of countries have yet to submit their new NDCs.

There are several reasons for this. The last round of NDCs was pushed back by a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, giving countries only four years to prepare new plans. Geopolitical tensions, ongoing conflicts and security concerns have further complicated progress. Many smaller developing nations are also facing capacity constraints as they work to complete biennial climate progress reports and new national adaptation plans (NAPs), also due this year.

Most countries are now expected to present their new NDCs by the UN General Assembly in September.

Compared to previous targets, the NDCs submitted so far have made a noticeable but modest dent in the 2035 "emissions gap": the difference between where emissions need to be in 2035 to align with 1.5 degrees C and where they're expected to be under countries' new climate plans.

If fully implemented, new NDCs are projected to reduce emissions by 1.4 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) by 2035 when compared to 2030. Looking only at unconditional NDCs (those that don't require international support), this leaves a remaining emissions gap of 29.5 GtCO2e to hold warming to 1.5 degrees C. When conditional NDCs (those that do require international support) are included, this gap shrinks to 26.1 GtCO2e.

Much of the progress in narrowing the gap comes from major emitters that have already submitted new NDCs — most notably the U.S., Japan and Brazil. Given their large emissions profiles, their new commitments account for the majority of the reductions seen so far.

While this marks progress, it's far from what's needed to keep global warming within safe limits. Getting on track to 1.5 or even 2 degrees C would require much steeper cuts than what's currently on the table.

However, this is not the full picture.

Many of the world's largest emitters have yet to submit their 2035 targets. The remaining G20 countries alone account for about two-thirds of global GHG emissions. This makes their forthcoming NDCs especially important: The scale and ambition of these commitments could meaningfully narrow the emissions gap — or, if they fall short, leave the world locked into a trajectory that puts global temperature targets out of reach.

Among the countries that have submitted new NDCs so far, the United Kingdom stands out for its ambitious climate trajectory. Following the recommendations of its Climate Change Committee, the U.K. has set a bold target to reduce emissions 81% by 2035 from 1990 levels. This rapid decline in the coming decade would put the country on track toward its net zero goal by 2050, based on realistic rates of technology deployment and ambitious but achievable shifts in consumer and business behavior.

Other countries, such as Japan and the United States, have opted for a "linear" approach toward net zero — meaning if they drew a straight line to their net-zero target (for example, 0 GtCO2e in 2050), their 2030 and 2035 targets would fall along it, reflecting a constant decline in emissions each year. Japan aims to cut emissions 60% from 2013 levels by 2035, while the United States has pledged a 61%-66% reduction from 2005 levels by 2035.

Despite the U.S. withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, undermining climate policies and attempting to dismantle key government institutions, its NDC target may still provide a framework for climate action at the state, city and local levels, as well as for future administrations. Many of these entities have already rallied around the new NDC and are committed to making progress toward its targets.

However, the linear approach Japan and the U.S. are taking to emissions reductions — as opposed to a steeper decline this decade — risks using up a larger share of the world's carbon budget earlier and compromising global temperature targets.

Brazil presented a broader range of emissions targets in its NDC, committing to a 59%-67% reduction by 2035 from 2005 levels. These two poles represent a marked difference in ambition: A 67% reduction could put Brazil on track for climate neutrality by 2050, while a 59% reduction falls short of what's needed to meet that goal. It is unclear which trajectory the government intends to pursue, leaving Brazil's true ambition in question. The NDC also omits carbon budgets for specific sectors (such as energy, transport or agriculture), which would clarify how it plans to meet its overarching emissions goals. However, Brazil committed within its NDC to develop further plans outlining how each sector will contribute to its 2035 target.

Elsewhere, Canada made only a marginal increase to its target, shifting from a 40%-45% emissions reduction by 2030 to 45%-50% by 2035 from 2005 levels. This falls short of the recommendation from Canada's own Net-Zero Advisory Body, which called for a 50%-55% reduction by 2035 — and warned that anything below 50% risks derailing progress toward the country's legislated net-zero goal by 2050. While every increase in ambition counts, such incremental changes do not match the urgent pace of progress needed among developed and wealthy economies like Canada.

Several early trends are starting to emerge among the new NDCs. While these initial submissions offer valuable insights, they don't yet reflect the full picture; deeper analysis will be needed as more NDCs come in throughout the year.

Almost all of the 22 NDCs submitted thus far include 2035 mitigation measures. The exception is Zambia, which reiterated its previous 2030 pledges in a provisional NDC (although this may still be revised to include 2035 mitigation measures).

Of the other 21 submissions, 20 countries expressed their 2035 targets as emissions-reduction goals. The exception was Cuba, which instead committed to increasing renewable electricity generation to 26% and improving energy efficiency by 2035.

Seventeen of the 20 countries with emissions-reduction goals set economy-wide reduction targets for 2035, as encouraged by the Global Stocktake, covering all sectors and greenhouse gases. The remaining few — smaller developing countries such as the Maldives and Nepal — submitted targets that cover only specific sectors or gases.

Under the Paris Agreement, developed countries are required to submit economy-wide targets, while developing countries are encouraged to work toward them over time. In Nepal's case, for instance, a lack of comprehensive data limited its ability to define an economy-wide target or fully assess the impact of its policies.

Despite clear scientific evidence and UN decisions urging stronger 2030 targets, only four countries — Saint Lucia, Nepal, Moldova and Montenegro — have strengthened their 2030 emissions pledges. For example, Montenegro revised its emissions-reduction target from 35% to 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, and set a 60% emissions-reduction target by 2035.

Notably, none of the wealthier, high-emitting and more developed countries have strengthened their 2030 targets — despite having the greatest capacity and responsibility to take the lead on slashing emissions.

In the face of worsening climate impacts, 16 of the 22 countries that have submitted new NDCs strengthened their adaptation commitments — continuing a trend seen in previous rounds. Countries are prioritizing adaptation across sectors such as food and water systems, public health and nature-based solutions.

Ecuador, which is particularly vulnerable to heavy rainfall and floods, prioritized action to build resilience of its water resources, human health and settlements, as well as its natural heritage. Some developed countries are also prioritizing adaptation action in their NDCs. Canada, which has witnessed devastating wildfires in recent years, cited its National Adaptation Strategy, which provides a framework for disaster resilience, biodiversity, public health and infrastructure.

Some countries' NDCs also recognize the critical role that subnational actors — such as cities, states and regions — play in shaping and delivering climate action.

Eleven of the newly submitted NDCs come from countries that have endorsed the Coalition for High Ambition Multilevel Partnerships (CHAMP). The CHAMP initiative — launched in 2023 by the COP28 Presidency, in partnership with Bloomberg Philanthropies and with the support of WRI and other partners — aims to strengthen collaboration between national and subnational governments on climate planning and implementation. As part of this commitment, 75 countries pledged to consult with and integrate subnational priorities and needs into their NDCs. Of the 11 endorsing countries that have submitted new NDCs, four explicitly mentioned CHAMP.

Brazil's NDC in particular recognizes the critical role subnational governments play in delivering national climate goals. Referred to as "climate federalism," it highlights an instrument designed to support the integration of climate action into planning and decision-making across all levels of government: federal, state and municipal.

As countries submit new NDCs for the first time since the Global Stocktake in 2023, a clearer picture is emerging of how governments are embedding sector-specific action into their new climate plans. From detailed emissions-reduction targets to broader policy frameworks, most NDCs are setting out concrete steps to cut emissions across sectors that largely drive climate change, such as energy, transport and forestry.

Some countries — such as Switzerland, the UAE, Kenya and Zimbabwe — have included sector-specific emissions-reduction targets directly in their NDCs. Switzerland's targets, for instance are aligned with its Climate and Innovation Act, with plans to cut emissions by 66% in buildings, 41% in transport and 42.5% in industry by 2035 compared to 1990 levels. Kenya, on the other hand, has set an ambitious target to achieve 100% renewable electricity generation in the national grid by 2035.

Others, like the United Kingdom, Brazil, Singapore, the Marshall Islands and Canada, have focused on elaborating national policies and strategies that respond to the Global Stocktake's priority areas. The U.K.'s NDC highlighted its Clean Power 2030 Action Plan to fully decarbonize electricity by 2030; the Warm Homes Plan to boost energy efficiency in residential buildings; and reaffirmed its plans for phasing out internal combustion engine vehicles by 2030.

Countries such as Brazil and New Zealand have committed to developing detailed sectoral strategies as a next step to support NDC implementation. Brazil plans to update its national climate strategy by mid-2025, breaking it down into 16 sectoral adaptation plans and seven mitigation plans. New Zealand committed to publishing its emissions-reduction plan for 2031-2035 in 2029, which will set out sectoral mitigation strategies to help deliver on its NDC.

As more countries prepare to submit their new NDCs, attention will focus on whether they follow the trend of outlining sector-specific actions to meet their broader emissions targets. In particular, the spotlight will be on how countries plan to contribute to the transition away from fossil fuels — the single largest driver of the climate crisis.

We have yet to see new NDCs from many major emitters, including the European Union, China and India. All three have demonstrated climate leadership in various ways, and their actions will set the tone for future climate efforts. While these three are in the spotlight, attention will also be on other key countries — such as Indonesia, Mexico and Australia -— that are critical to reducing the global emissions gap.

The EU is still working to set a 2035 emissions target for its new NDC, which will hinge on its longer-term 2040 target. Last year, the European Commission recommended cutting emissions 90% by 2040 — a move that's seen as beneficial for enhancing industrial competitiveness in clean technologies, strengthening energy security and cutting energy costs. Some EU member states have suggested following a linear trajectory between the 2030 and 2040 targets, which would imply a 72.5% reduction by 2035 if the 90% target for 2040 gets adopted.

However, European member states have yet to adopt the 90% target. Ongoing discussions could see the EU's target weakened to address concerns from heavy industry and agriculture. The delay in finalizing the EU's 2040 target is also putting its NDC timeline at risk, raising the possibility of missing the expected September submission date.