The rooftop solar industry is facing an unprecedented crisis. Utilities are cutting incentives. Major residential solar installers and financiers have gone bankrupt. And sweeping legislation just passed by Republicans in Congress will soon cut off federal tax credits that have supported the sector for 20 years.

But the fact remains that solar panels — and the lithium-ion batteries that increasingly accompany them — remain the cheapest and most easily deployable technologies available to serve the ever-hungry U.S. power grid.

Sachu Constantine, executive director of nonprofit advocacy group Vote Solar, thinks that the rooftop solar and battery industries can survive and even thrive if they focus their efforts on becoming “virtual power plants.”

Hundreds of thousands of battery-equipped, solar-clad homes across the country are already storing their renewable energy when it’s cheap and abundant and then returning it to the grid when electricity demand peaks and utilities face grid strains and high costs — in essence, acting as “peaker” power plants.

In places like Puerto Rico and New England, these VPPs have demonstrated their worth in recent months, preventing blackouts and lowering costs for consumers, and the approach could be scaled up dramatically. “If we do that, despite the One Big Beautiful Bill, despite the headwinds to the market, there is space for these technologies,” Constantine said.

Right now, there aren’t many other options for meeting soaring energy demand, he added. The megabill signed by President Donald Trump this month undermines the economics of the utility-scale solar and battery installations that make up the vast majority of new energy being added to the grid. And despite the Trump administration’s push for fossil fuels, gas-fired power plants can’t be built fast enough to make up the difference.

Meanwhile, the U.S. power grid has not expanded quickly enough, increasing the risk of outages and subjecting Americans to the burden of rising utility rates, Constantine said. State lawmakers and utility regulators are under growing pressure to find solutions.

Solar and batteries, clustered in small-scale community energy projects or scattered across neighborhoods, may be “the only viable way to meet load growth” from data centers, factories, and broader economic activity, Constantine said. And by relieving pressure on utility grids, they can help bring down costs not just for those who install them, but for customers at large.

This summer has brought new proof of how customers can turn their rooftop solar systems and batteries to the task of rescuing their neighbors from energy emergencies. Over the past two months, Puerto Rico grid operator LUMA Energy has relied on participants in its Customer Battery Energy Sharing program to prevent the grid from collapsing.

“Last night we successfully dispatched approximately 70,000 batteries, contributing around 48 megawatts of energy to the grid,” LUMA wrote in a July 9 social media post in Spanish. Amid a generation shortfall of nearly 50 MW, that dispatch helped avert “multiple load shedding events” — the industry term for rolling blackouts.

Puerto Ricans have been installing solar and batteries at a rapid clip since 2017, when Hurricane Maria devastated the island territory’s grid and left millions of people without power, some for nearly a year.

“There were tens of thousands of batteries already there that just needed to get connected in a more meaningful way,” said Shannon Anderson, a policy director focused on virtual power plants at Solar United Neighbors, a nonprofit that helps households organize to secure cheaper rooftop solar. “The numbers have been really proven out this summer in terms of what it’s been able to do.”

Puerto Rico’s VPPs are managed by aggregators — companies that install solar and battery systems and control them to support the grid. Tesla Energy, one such aggregator, provides live updates on how much the company’s Powerwall batteries are contributing to the system at large.

The impacts of distributed solar and batteries aren’t always so easy to track — but clean-energy advocates are busy calculating where they’re making a difference.

During last month’s heat wave across New England, as power prices spiked and grid operators sought to import energy from neighboring regions, distributed solar and batteries reduced stress on the grid. Nonprofit group Acadia Center estimated that rooftop solar helped avoid about $20 million in costs by driving down energy consumption and suppressing power prices.

A good portion of that distributed solar operates as part of the region’s VPPs. The ConnectedSolutions programs run by utilities National Grid and Eversource cut demand by hundreds of megawatts during summer heat waves. And Vermont utility Green Mountain Power has been a vanguard in using solar-charged batteries as grid resources at a large scale, in concert with smart thermostats, EV chargers, and remote-controllable water heaters. All told, that scattered infrastructure gives the company 72 extra megawatts of capacity to play with during grid emergencies.

Mary Powell, who led Green Mountain Power’s push into VPPs before that term had caught on, left to become CEO of Sunrun, the country’s largest residential solar installer, in 2021. Choosing to hire Powell indicated the company’s growing interest in becoming something of a solar-powered utility.

This summer, Sunrun dispatched hundreds of megawatts from more than 130,000 batteries across California, New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Puerto Rico. It recently expanded into Texas’ competitive energy, in partnership with Tesla.

“We are living in the future of virtual power plants in places like Puerto Rico, and California, and New England, and increasingly Texas,” said Chris Rauscher, Sunrun’s head of grid services and electrification. “It’s just about other states putting that in place in their territories and letting it run.”

Sunrun, Vote Solar, and Solar United Neighbors have been working for the last year to advance state policies that support VPPs. So far this year, the groups have promoted model VPP legislation in states including Illinois, Minnesota, New Mexico, Oregon, and Virginia.

In May, Virginia passed a law requiring that utility Dominion Energy launch a pilot program to enlist up to 450 megawatts of VPP capacity, including at least 15 MW of home batteries, Anderson said.

The legislative effort has had less luck in New Mexico and Minnesota, where bills failed to advance, Anderson said. In Illinois, a proposed bill did not pass during the regular legislative session, but advocates hope to bring it back for consideration during the state’s “veto session” this fall, she said.

A lot more batteries are being added to rooftop solar systems in Illinois, Anderson noted — a byproduct of the state clawing back net-metering compensation for solar-equipped customers starting this year. Similar dynamics have played out in Hawaii and California after regulators reduced the value of solar power that customers send back to the grid, making batteries that can store extra power and further limit customers’ grid consumption much more popular.

Rooftop solar advocates have fought hard to retain net-metering programs across the country. But Jenny Chase, solar analyst with BloombergNEF, noted that most mature rooftop solar markets have shifted away from rewarding customers for sending energy back to the grid at times when it’s not needed.

“In some ways that’s justified, because net metering pushes all responsibility and cost of intermittency onto the utility,” she said.

VPPs flip this dynamic, turning rooftop solar and batteries from a potentially disruptive imposition on how utilities manage and finance their operations to an active aid in meeting their mission of providing reliable power at a reasonable cost. Utilities have traditionally been leery of trusting customer-owned resources to meet their needs. But under pressure from lawmakers and regulators, they’re starting to embrace the possibilities.

In Minnesota, utility Xcel Energy has proposed a “distributed capacity procurement” program that would allow it to own and operate solar and batteries installed at key locations, letting the company defer costly grid upgrades. Rooftop solar advocates have mixed feelings about the proposal, given their longstanding complaints about Xcel’s track record of making it more difficult for customers and independent developers to build their own solar and battery systems.

Similar tensions are at play in Colorado, where Xcel is under state order to build distributed energy resources like rooftop solar and batteries into how it plans and manages its grid. This spring, Xcel launched a project with Tesla and smart-meter company Itron aimed at “taking these thousands of batteries we have connected to this system over time and [being] able to use them to respond to local issues,” Emmett Romine, the utility’s vice president of customer energy and transportation solutions, told Canary Media in an April interview.

But waiting for utilities to deploy the grid sensors, software, and other technology needed to perfectly control customers’ devices runs the risk of delaying the growth of VPPs, Anderson said. Simpler approaches like those being taken in Puerto Rico — where aggregators manage VPPs — can do a lot of good quickly. “Once you get that to scale, there will be a lot of learnings for the next stage,” she said

State- and utility-level incentives that encourage individuals to participate in VPPs are also a vital countermeasure against the damage incurred by the “big, beautiful bill” passed by Republicans this month, Anderson said. Under that law, households will lose a 30% tax credit that offsets the cost of solar, batteries, and other home energy systems by the end of this year.

However, companies such as Sunrun and Tesla will retain access to tax credits for solar systems that they own and provide to customers through leases or power purchase agreement structures, as long as they begin construction by mid-2026 or are placed in service by the end of 2027. And tax credits for batteries remain in place until 2033 for these companies.

VPP programs can’t make up for the loss of the tax credit for customers who haven’t yet installed solar or batteries, Anderson said. But by financially rewarding participants, they can help consumers recoup initial costs, she said, as long as they aren’t hampered by ineffective state policies.

“Folks can earn over $1,000 a summer through [some VPPs],” she said. “You couple in the leasing model for solar and storage, which is going to get a little more popular in the aftermath of the bill,” due to its ability to continue to earn tax credits, “and I think it’s a pretty good way to get batteries for low or no cost up front.”

It’s getting easier and easier to find a public EV charger in the U.S.

Between 2020 and 2024, the number of public EV charging ports available to U.S. drivers doubled, reaching nearly 200,000 by the end of last year, according to International Energy Agency data. Northeast states have the highest charger density by far, with Massachusetts at the top of the list.

It’s solid growth, though significantly slower than other regions that have embraced EVs more wholeheartedly. In Europe and China, both of which are adopting EVs much faster than the U.S., public chargers roughly quadrupled over the same period.

Even though an estimated 80% of charging happens at home in the U.S., concerns about a lack of public charging infrastructure have dogged EV adoption for years. American drivers consistently cite the issue, or its close cousins, like a fear that EVs are no good for road trips, as among the top reasons they are unlikely to get an electric car.

That’s why widely available public EV charging ports are so important to the transition to electric vehicles — a shift that needs to happen for the U.S. to clean up transportation, its biggest source of carbon emissions.

If the number of public plugs continues to grow at the rate observed in recent years, the industry would have over half a million public charging ports available by 2030, enough to meet a goal set by the Biden administration years ago.

That might be a big “if” under President Donald Trump.

Since taking office in January, Trump has tried to freeze billions of dollars’ worth of federal funding for public EV charging authorized by the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law. A judge ruled last month that the administration must turn the spigot back on. The program was already sluggish to begin with, having funded the installation of just a couple hundred charging ports over the last four years, and the Trump turmoil has only thrown more sand in its gears.

Then there’s the possibility that EV sales slow down in the U.S. after Sept. 30, when Trump’s megabill eliminates federal tax credits for consumers. Fewer EVs hitting the road could undermine the economic case for companies to build new charging stations.

Still, it’s true that chargers are becoming a more familiar sight for drivers — especially those in the Northeast. As time goes on, that familiarity should help erode the stubborn perception that EVs are unworkable, and help push more and more people to embrace electric, emissions-free driving.

So far, 2025 has been a mixed bag for EV sales in the U.S. A record 607,089 EVs left the lot in the first six months of the year, Cox Automotive reports, but sales in the second quarter were still lower than in Q2 2024.

A big part of that Q2 decline has to do with Tesla, which remains the U.S.’s top EV seller but has suffered stateside and around the world thanks to CEO Elon Musk’s stint in the White House. This week, Tesla reported its profits dropped 16% in Q2 compared to the same period last year. Tesla doesn’t report its sales, but it delivered nearly 60,000 fewer vehicles in Q2 compared to a year ago.

General Motors, meanwhile, had better news to share. It sold 46,280 EVs in Q2, more than double its sales in the same period last year. That’s still a far cry from Tesla’s 380,000-plus deliveries, but it was enough to make GM the No. 2 EV brand in the U.S. And slower EV sales across the industry aren’t deterring GM CEO Mary Barra, who said the company sees EV production as its “North Star.”

Rivian reported a delivery decline in the second quarter but still plans to build new headquarters and an EV factory in Georgia. Smaller EV company Lucid says it delivered a record 3,309 cars in Q2.

Be prepared, though, for a rollercoaster in the next few months now that the “Big, Beautiful Bill” has sent EV tax credits to an early grave. Cox Automotive predicts EV sales will hit a new record in Q3 as buyers race to use federal incentives before they expire at the end of September. After that? “A collapse in Q4, as the electric vehicle market adjusts to its new reality.”

Trump calls off loan for major transmission line

The Trump administration this week canceled a $4.9 billion federal loan guarantee for the Grain Belt Express, putting its future in jeopardy, Canary Media’s Jeff St. John reports.

The planned transmission line, which was granted its loan guarantee under the Biden administration, is meant to bring wind and solar power generated in the Great Plains to cities further east. It has been in the works for more than a decade, and construction on its first phase was slated to start next year.

While the Grain Belt Express had support from utility regulators and large electricity consumers along the line’s route, Missouri Republicans turned against it in recent weeks. The state’s Republican attorney general launched an investigation into the project earlier this month, and Sen. Josh Hawley said he made a direct appeal to President Trump to pull back federal support.

Can the EPA revoke all its emissions rules at once?

The U.S. EPA is planning to demolish the bedrock of many of its climate change-fighting regulations, The New York Times reports. The agency is reportedly preparing a rule that would rescind the 2009 “endangerment finding,” which scientifically established that greenhouse gases harm human health. That finding underpins many of the EPA’s landmark emissions rules, including regulations targeting pollution from cars, factories, and power plants. If the finding is revoked, it would immediately end all those limits and make it harder for future presidential administrations to reinstate them.

The draft of the rule change doesn’t dispute that climate pollutants like carbon dioxide and methane drive global warming or put people’s health at risk, according to the Times. Instead, it claims the endangerment finding oversteps the EPA’s authority. The new rule is almost certain to face legal challenges if it’s finalized.

A “shadow ban” on renewables? Democrats, advocates, and industry groups push back on the Trump administration’s decision to heighten reviews for proposed solar and wind projects on federal land, saying it could lead to a clean energy “shadow ban.” (E&E News)

Shaving solar costs: Solar industry veteran Andrew Birch says cutting non-equipment costs like permitting and project management can reduce the price of rooftop solar installations as federal incentives expire. (Canary Media)

Reeling in the deep: The U.S. government’s step toward issuing The Metals Co. deep-sea mining permits conflicts with an international treaty, leaving the startup’s partners abroad wary of continuing to work together. (New York Times)

Can SMRs succeed? Nuclear industry leaders say there’s enough momentum and funding behind small modular reactor development to propel the sector beyond its past failures. (Canary Media)

Data center downgrade: OpenAI’s Stargate project softens its ambitious plans and is now only looking to build one small data center this year, which could have fallout for energy developers who would have powered the projects. (Wall Street Journal)

Carbon capture’s secret supporters: The oil and gas industry has played a big role in crafting an Ohio carbon-capture bill that could help keep fossil fuel operations running. (Canary Media)

Rates on the rise: U.S. utilities have requested or secured a record $29 billion in rate increases in the first half of the year, more than double the total reached halfway through 2024. (Latitude Media)

A controversial bill to unravel North Carolina’s climate law would cost the state more than 50,000 jobs annually and cause tens of billions of dollars in lost investments, a new study finds. The research comes days before the Republican-controlled state legislature aims to override a veto of the measure by Gov. Josh Stein, a Democrat.

First passed by the Senate in March, the wide-ranging Senate Bill 266 repeals the 2030 deadline by which utility Duke Energy must curb its climate pollution 70% compared to 2005 levels. It leaves intact a mandate that the company achieve carbon neutrality by midcentury.

Senate leader Phil Berger, a 13-term Republican from Rockingham County, has said his chamber will vote on the override Tuesday, July 29. The House, which approved the bill with bipartisan support in June, could attempt an override of Stein’s July 2 veto the same day.

Conducted by BW Research for clean energy nonprofits, the new analysis draws on earlier projections from Public Staff, the state-sanctioned customer advocate. That modeling showed that without a near-term climate goal, Duke would build about 40% less new generation capacity over the next decade — leaning harder instead on aging fossil-fueled units to meet demand.

The fresh research calculates the economic losses of foregoing those new power plants, including massive amounts of solar and wind along with 300 megawatts of new nuclear and 1,400 megawatts of combined-cycle gas plants.

From 2030 to 2035, North Carolina would see nearly 50,700 fewer jobs annually and over $47.2 billion sacrificed in power-plant construction, the study says. More than $1.4 billion in tax revenue would also be left on the table.

“This study conveys in real terms the impact of arbitrarily removing a market signal that has proven to be a job creator and an economic booster for North Carolina,” said Josh Brooks, chief of policy strategy and innovation with the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association.

BW Research finds that if SB 266 became law, Duke would have 12 fewer gigawatts of capacity in 2035 to meet peaks in power demand, like those that happen on unusually cold winter mornings. Experts say the company would likely have to purchase more out-of-state power or rely more heavily on fossil fuels as a result.

“This limitation hampers the state’s ability to meet current energy needs and undermines its competitive edge in attracting energy-intensive industries,” the analysts say.

The new study is the second to show how Public Staff’s modeling belie claims from SB 266 proponents that the bill will save money and promote more power generation.

Late last month, three researchers from North Carolina State University found that with fewer solar, wind, and nuclear plants as projected by Public Staff, Duke would have to burn almost 40% more natural gas between 2030 and 2050.

Under a worst-case but plausible scenario for gas prices, the trio found, customers could pay $23 billion more in fuel costs on their electric bills by midcentury as a result. The figure would cancel out projected consumer savings from building fewer new sources of generation, a fact not lost on the governor.

“My job is to do everything in my power to lower costs and grow the economy,” Stein said in a statement when he vetoed SB 266 early this month. “This bill fails that test.”

In his veto message, Stein also referenced another study, from EQ Research, showing the measure would make energy more expensive for North Carolina households.

“[SB 266] shifts the cost of electricity from large industrial users onto the backs of regular people,” Stein said. “Families will pay more so that industry pays less.”

Still, the findings from independent researchers and the three NC State professors may not be enough to counter the lingering narrative that SB 266, dubbed the Power Bill Reduction Act, will help customers.

Duke Energy and major industrial groups have lined up in support of the measure — the latter falsely suggesting that solar power investments have raised electric rates.

The North Carolina Chamber, the state’s major business lobby, says the bill’s enactment would provide “businesses and consumers with more affordable, predictable energy costs.” The group plans to include SB 266 in its annual scorecard rating legislators’ performances.

Perhaps most daunting for clean energy advocates and other bill opponents is that several Democrats appear swayed by these arguments. While Republicans have enough members to overrule Stein in the upper chamber, they’re one vote shy in the House. With all members present, that means the 11 House Democrats who previously voted for SB 266 would need a change of heart to uphold Stein’s veto.

House Speaker Destin Hall, a Republican from Caldwell County, says that won’t happen.

“I’m disappointed in the governor’s veto of the ‘Power Bill Reduction Act,’ which would have delivered cheap, reliable energy to North Carolina, cut the red tape that is choking innovation and long-term energy solutions, and saved consumers over $12 billion dollars,” Hall said in statement moments after Stein rejected the bill. “Considering the strong bipartisan support in both chambers, we anticipate overriding this veto.”

But Will Scott, Southeast climate and clean energy director for the Environmental Defense Fund, hopes the study will help change lawmakers’ minds.

“This shows that passing this legislation is going to have negative consequences for our ability to meet growing demand,” he said, “and that’s going to have knock-on economic impacts across the state.”

The highest court of the UN has issued a landmark “advisory opinion” stating that nations can be held legally accountable for their greenhouse-gas emissions.

Recognising the “urgent and existential threat” facing the world, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) concluded that those harmed by human-caused climate change may be entitled to “reparations”.

Their opinion largely rests on the application of existing international law, clarifying that climate “harms” can be clearly linked to major emitters and fossil-fuel producers.

The case, which was triggered by a group of Pacific island students and championed by the government of Vanuatu, saw unprecedented levels of input from nations.

In a unanimous decision issued on 23 July, the 15 judges on the ICJ concluded that the production and consumption of fossil fuels “may constitute an internationally wrongful act attributable to that state”.

The opinion also says that limiting global warming to 1.5C should be considered the “primary temperature goal” for nations and, to achieve it, they are obliged to make “adequate contributions”.

While the ICJ opinion is not binding for governments, it could have significant influence as vulnerable groups and nations push for stronger climate action or seek compensation in court.

Below, Carbon Brief explains the most important aspects of the ICJ’s 133-page advisory opinion and speaks to legal experts about its implications.

The case stems from a campaign led by 27 students from the University of the South Pacific in Fiji.

In 2019, they established a youth-led grassroots organisation – dubbed the Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change (PISFCC) – and began efforts to persuade the leaders of the Pacific Islands Forum to take the issue of climate change to the world’s top court.

PISFCC joined forces with other youth organisations from around the world in 2020, lobbying state representatives to take action.

In 2021, the government of Vanuatu announced that it would lead efforts to gain an “advisory opinion” from the ICJ. It worked to engage with the Pacific island community first, to build a “coalition of like-minded vulnerable countries”, reported Climate Home News.

Following on from this work, Vanuatu received a unanimous endorsement for its efforts from the 18 members of the Pacific Island Forum. It continued to work diplomatically, engaging in discussions across Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America to encourage other countries to join the effort.

After three rounds of consultations with other states, the resolution was put before the UN general assembly with the backing of 105 sponsor countries.

Finally, on 29 March 2023, the assembly unanimously adopted the resolution formally requesting an “advisory opinion” from the ICJ.

The resolution posed two questions for the ICJ. In answering these questions, it asked the court to have “particular regard” to a range of laws and principles, including the UN climate regime and the universal declaration on human rights.

First, the resolution asked what are the legal obligations of states under international law to “ensure the protection of the climate system”.

Second, it asked what are the legal consequences flowing from these obligations if states, by their “acts or omissions”, have caused “significant harm to the climate”.

The resolution asked for the court to consider, in particular, states that are “specially affected” or are “particularly vulnerable” to the impacts of climate change.

It also pointed to “peoples and individuals of the present and future generations affected by the adverse effects of climate change”.

Therefore, the advisory opinion issued this week by the ICJ, in response to these questions, is the culmination of a years-long process.

Although the opinion is not binding on states, it is binding on UN bodies and is likely to have far-reaching legal and political consequences at a national level.

The ICJ was tasked with interpreting international law and arriving at an advisory opinion. While its legal advice will, therefore, not be binding for nations, it will be binding for other UN bodies.

This two-year process involved the judges defining the scope and meaning of the broad questions put to them by the UN general assembly. (See: How did the case come about?)

They then considered which international laws and principles were relevant for these questions.

Among the relevant laws identified were the three UN climate change treaties – the UNFCCC, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

They also considered various other treaties covering biodiversity, ozone depletion, desertification and the oceans, as well as legal principles such as the principle of “prevention of significant harm to the environment”.

The ICJ’s process has also seen nations and international groups, such as the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec), offer their views on the case.

These groups had the opportunity to feed into the judges’ deliberations over several stages, including two sets of written submissions, followed by oral statements to the court.

In total, the court received 91 written statements, a further 107 oral statements – delivered at the Hague in December 2024 – and 65 responses to follow-up questions by the judges.

This is the “highest level of participation in a proceeding” in the court’s history, according to the ICJ. Some nations, including island states such as Barbados and Micronesia, appeared before the court for the first time ever.

These contributions demonstrated broad agreement among nations that climate change is a threat and that emissions should be cut in order to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

But there were major divergences on the breadth and nature of obligations under international law to act to limit global warming, as well as on the consequences of any breaches, as specifically being addressed by the ICJ.

Overall, the main divisions were between high-emitting nations trying to limit their climate obligations and low-emitting, climate-vulnerable nations, who were pushing for broader legal obligations and stricter accountability for any breaches.

Specifically, “emerging” economies such as China and Saudi Arabia, along with historical high-emitters such as the UK and EU, argued that climate obligations under international law should be defined solely by reference to the UN climate regime.

In contrast, vulnerable nations said that wider international law should also apply, bringing additional obligations to act – and the potential for legal consequences, including reparations.

This is a departure from UN climate talks, where the main divide tends to be between “developed” and “developing” countries – with the latter encompassing both high- and low-emitting nations.

In an unusual move, the ICJ judges also organised a private meeting in November 2024 with scientists representing the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Among those present were IPCC chair Prof Jim Skea and eight other climate scientists from various countries and with different areas of expertise.

A statement issued by the ICJ said this was an effort to “enhance the court’s understanding of the key scientific findings which the IPCC has delivered”.

On 23 July 2025, after some seven months of deliberation, the ICJ issued a unanimous opinion in response to the UN general assembly’s request.

This is only the fifth time the court has delivered a unanimous result, according to the ICJ, after nearly 88 years in operation and 29 opinions.

(In addition to the unanimous opinion of the full court, several of the ICJ judges also issued their own declarations and opinions, individually or in small groups.)

When considering the “context” for the issuing of the advisory opinion on climate change, the court provides information on the “relevant scientific background”.

This was drawn from reports by the IPCC, which the court says “constitute the best available science on the causes, nature and consequences of climate change”.

It comes after ICJ judges held a private meeting with IPCC scientists in 2024. (See: How has the case been decided?)

The advisory opinion states that it is “scientifically established that the climate system has undergone widespread and rapid changes”, continuing:

“While certain greenhouse gases [GHGs] occur naturally, it is scientifically established that the increase in concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere is primarily due to human activities, whether as a result of GHG emissions, including by the burning of fossil fuels, or as a result of the weakening or destruction of carbon reservoirs and sinks, such as forests and the ocean, which store or remove GHGs from the atmosphere.”

It continues that the “consequences of climate change are severe and far-reaching”, listing impacts including the “melting of ice sheets and glaciers, leading to sea level rise”, “more frequent and intense” extreme weather events and the “irreversible loss of biodiversity”. The document adds:

“These consequences underscore the urgent and existential threat posed by climate change.”

The advisory opinion further adds that the “IPCC notes that adaptation measures are still insufficient” and that “limits to adaptation have been reached in some ecosystems and regions”.

On the need to address rising emissions, the document quotes the IPCC directly, saying:

“According to the panel, climate change is a threat to ‘human well-being and planetary health’ and there is a ‘rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all’ (very high confidence). It adds that the choices and actions implemented between 2020 and 2030 ‘will have impacts now and for thousands of years’.”

It adds that the “IPCC has also concluded with ‘very high confidence’ that risks and projected adverse impacts and related loss and damage from climate change will escalate with every increment of global warming”.

In regards to how states should consider climate science when implementing climate policies and measures, the court says that countries should exercise the “precautionary principle”, adding:

“The court observes that where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

In response to the first question on legal obligations, the ICJ says that countries have “binding obligations to ensure protection of the climate system” under the UN climate treaties.

However, the court’s unanimous opinion flatly rejects the argument, put forward by high emitters, such as the US, UK and China, that these treaties are the end of the matter.

These nations had argued that the climate treaties formed a “lex specialis”, a specific area of law that precludes the application of broader general international law principles.

On the contrary, the ICJ says countries do have legal obligations under general international law, including a duty to prevent “significant harm to the environment”, with further obligations arising under human rights law and from other treaties.

As such, the court, “essentially sided with the global south and small island developing states”, says Prof Jorge Viñuales, Harold Samuel professor of law and environmental policy at the University of Cambridge.

Moreover, the court finds that countries’ obligations extend not only to greenhouse gas emissions, but also to fossil-fuel production and subsidies, says Viñuales, who acted for Vanuatu in the case.

Speaking to Carbon Brief in a personal capacity, he says: “That is important because major producers are not necessarily major emitters and vice-versa.”

In terms of the UN climate treaties, such as the Paris Agreement, the court affirms that these give countries binding obligations including adopting measures to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change.

Developed countries – parties listed under Annex I of the UNFCCC – have “additional obligations to take the lead in combating climate change”, the ICJ notes.

States also have a “duty” to cooperate with each other in order to achieve the objectives of the UNFCCC, acting in “good faith” to prevent harm, it adds.

Beyond the climate treaties, it says that “states have a duty to prevent significant harm to the environment”. Therefore, they must act with “due diligence” and use “all means at their disposal” to prevent activities carried out within their jurisdiction or control from causing “significant harm” to the climate system.

The court sets out the “appropriate measures” that would demonstrate due diligence, including “regulatory mechanisms…designed to achieve deep, rapid and sustained reductions” in emissions. This repeats language from the IPCC, but attaches it to countries’ legal obligations.

As with action under the climate treaties, countries’ obligations under broader international law should be taken in accordance with the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” it adds, a point reaffirmed throughout the advisory opinion.

Furthermore, countries have obligations to act on climate under a raft of other international agreements, covering the ozone layer, biological diversity, desertification and the UN convention on the law of the sea, the ICJ notes.

The court affirms that states that are not party to UN climate treaties must still meet their equivalent obligations under customary international law. This “addresses the unique situation of the US, but without naming it”, notes Sébastien Duyck, a senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law, on Bluesky.

Following his re-election last year, US president Donald Trump signed an order to pull the country out of the Paris Agreement again. As such, there is a question around how the ICJ’s opinion might apply to the US – the country that has contributed more to human-caused climate change than any other nation.

Additionally, states have obligations under international human rights law to “respect and ensure the effective enjoyment of human rights by taking necessary measures to protect the climate system and other parts of the environment”, according to the ICJ.

This follows a ruling from the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in 2024 that found that the Swiss government’s climate policies violated human rights, as governments are obliged to protect citizens from the “serious adverse effects” of climate change.

Announcing the opinion to the Hague, judge Iwasawa Yuji, president of the court, said:

“The human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is essential for the enjoyment of other human rights.”

The second part of the advisory opinion deals with the “legal consequences” of countries causing “significant harm to the climate system and other parts of the environment”.

This refers to nations breaching their “obligations”, as defined in the first part of the opinion. (See: What does the ICJ say about countries’ climate obligations?)

Crucially, the court says that countries can, in principle, face liability for climate harms, opening the door to potential “reparations” for loss and damage. Prof Viñuales tells Carbon Brief:

“Perhaps the main take away from the opinion is that the court recognised the principle of liability for climate harm, as actionable under the existing rules.”

Prof Viñuales notes that the court says “climate justice is governed by the general international law of state responsibility, which provides solutions for the recurrent arguments levelled to escape liability for climate harm”.

Essentially, the ICJ rejects the notion that it is too difficult to hold countries accountable for climate damages.

Examples of breached obligations given by the court include failing to set out or implement climate pledges – known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs) – under the Paris Agreement, or to sufficiently “regulate emissions of greenhouse gases”.

The ICJ stresses that it is not responsible for pointing fingers at particular countries, only for issuing a “general legal framework” that countries can follow.

As part of this process, it lays out a justification for why states can be held responsible for climate change.

During the ICJ process, some countries argued that greenhouse gas emissions are not like other environmental damage, such as localised chemical pollution. They said that emissions arise from all sorts of regular activities and it is difficult to tie climate damage to specific sources.

Others argued that it is perfectly possible to attribute such damage to states that, for example, have laws to “promote fossil-fuel production and consumption”.

This is important, as the ICJ points out that attribution is necessary if an activity is to be defined as an “internationally wrongful act”. Ultimately, the court agrees that it is feasible to attribute climate damage to specific states, on a “case-by-case” basis.

The court also finds that it is possible, at least in principle, to link climate disasters to countries’ emissions, though it notes that the causal links may be “more tenuous” than for localised pollution. It cites IPCC findings that climate change has amplified heatwaves, flooding and drought, stating:

“While the causal link between the wrongful actions or omissions of a state and the harm arising from climate change is more tenuous than in the case of local sources of pollution, this does not mean that the identification of a causal link is impossible.”

With this established, the court sets out what the consequences could be for countries that are deemed to have carried out “wrongful acts”.

First, the ICJ stresses that nations must meet their existing climate obligations. This means that if, for example, a government publishes an “inadequate” NDC, a “competent court or tribunal” could order it to supply one that is consistent with its obligations under the Paris Agreement.

Second, it also says that if a state is found responsible for climate damage, it must stop and ensure that it does not happen again.

States may be required to “employ all means at their disposal” to carry out this duty, according to the ICJ. In practice, the court says that this could mean governments revoking administrative or legislative acts in order to cut emissions.

In theory, this could lead to more stringent climate policies. For example, Dr Maria Antonia Tigre, director of global climate change litigation at the Sabin Centre for Climate Change Law, tells Carbon Brief:

“The ICJ made clear that the standard of due diligence is stringent and that each state must do its utmost to submit NDCs reflecting its highest possible ambition. That may strengthen pressure – political, legal and public – on states to raise their climate targets, especially before the next global stocktake.”

Finally, the ICJ opens the door for countries to seek “reparations” for climate harms from other countries.

It says these reparations could be expressed in different ways – including paying compensation or issuing formal apologies for wrongdoing.

This outcome was widely celebrated by climate justice activists and vulnerable nations, who see it as ushering in a “new era” in the fight to obtain financial compensation for climate disasters.

Harj Narulla, a barrister at Doughty Street Chambers and legal counsel for the Solomon Islands, tells Carbon Brief:

“The ICJ’s ruling has provided a legal pathway for developing states to seek climate reparations from developed States…States can bring claims for compensation or restitution for all climate-related damage. This includes claims for loss and damage, but importantly extends to any harm suffered as a result of climate change.”

One of the most significant parts of the ICJ opinion is the assertion that nations and “injured individuals” can seek “reparations” for climate damage.

This ties in with a long and contentious history of climate-vulnerable nations in the global south seeking compensation from high-emitting nations.

The notion of “climate reparations” has often been linked to developing countries pushing for so-called “loss and damage” finance in UN climate negotiations, including the – ultimately successful – fight for a “loss-and-damage fund”.

However, the US and other big historical emitters have ensured that any progress on loss-and-damage funding has not left them legally accountable for their past emissions.

The Paris Agreement states explicitly that its inclusion of loss and damage “does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation”.

Crucially, the ICJ opinion makes it clear that such language does not override international law and states’ responsibilities to provide “restitution”, “compensation” and “satisfaction” to those harmed by climate change.

Danilo Garrido Alves, a legal counsel for Greenpeace International, tells Carbon Brief that this means loss-and-damage finance is not a replacement for reparations:

“If a state contributes to the loss and damage fund and at the same time breaches obligations…that does not mean they are off the hook.”

Legal experts, including Prof Viñuales, tell Carbon Brief that this outcome is not surprising, given its grounding in international law. He says:

“It is the correct understanding of international law, but, in law, progress often takes the form of moving from the implicit to the explicit and that’s what the court did.”

Nevertheless, the outcome could have major implications for climate politics and lead to a wave of new climate litigation. Dr Tigre, at the Sabin Centre for Climate Change Law, tells Carbon Brief:

“[It] could shift the conversation from voluntary climate finance to legal obligations to repair harm, particularly for vulnerable communities and states already suffering loss and damage.”

Notably, the court says that while some states are “particularly vulnerable” to climate change, international law “does not differ” depending on such status. This means that, in principle, all nations are “entitled to the same remedies”.

As for individuals or groups taking legal action for both “present and future generations”, the ICJ notes that their ability to do so does not depend on rules around “state responsibility”. Instead, they would depend on obligations being breached under “specific treaties and other legal instruments”.

The ICJ says that reparations would be determined on a case-by-case basis, noting that the “appropriate nature and quantum of reparations…depends on the circumstances”. It also notes that:

“In the climate change context, reparations in the form of compensation may be difficult to calculate, as there is usually a degree of uncertainty.”

The question of precisely which nations will be liable for paying climate reparations is also predictably complex. Much of this discussion centres around responsibility for emissions, both currently and in the past.

Under the Paris Agreement, “developed” countries – a handful of nations in the global north – are obliged to provide climate finance to “developing” countries, which includes major emitters such as China.

In ICJ submissions, major emitters and fossil-fuel producers categorised as “developing” under the UN system stressed their low historical emissions. Some developing countries blamed climate change on a small group of “developed states of the global north”.

For their part, some countries with high historical emissions argued that it is difficult to assign responsibility for climate change.

However, the ICJ concludes that this is not the case. It says it is “scientifically possible” to determine each state’s contribution, accounting for “both historical and current emissions”.

Therefore, while the court explicitly avoids identifying the countries responsible for paying reparations, it makes clear that historical responsibility should be accounted for when considering whether states have met their climate obligations.

Finally, the court also says that “the status of a state as developed or developing is not static” and that it depends on the “current circumstances of the state concerned”.

This is notable, given that the current definitions of these terms – which determine who gives and receives climate finance – are based on definitions from the early 1990s.

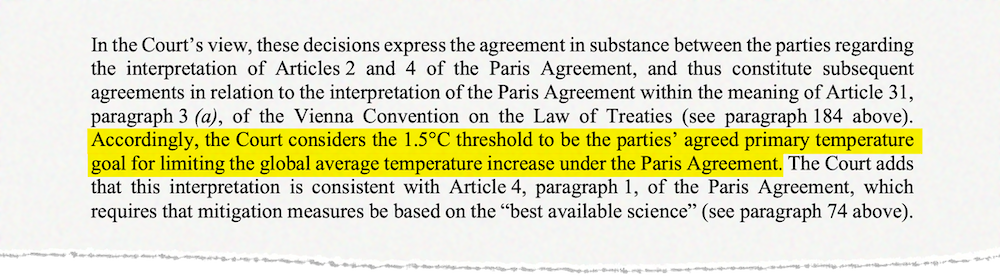

The advisory opinion offers clear guidance on the Paris Agreement and its aim to limit global temperature rise to “well-below” 2C by 2100, with an aspiration to keep warming below 1.5C.

It says that limiting temperature increase to 1.5C should be considered countries’ “primary temperature goal”, based on the court’s interpretation of the Paris Agreement.

The court adds that this interpretation is consistent with the Paris Agreement’s stipulation that efforts to tackle climate change should be based on the “best available science”.

(In 2018, four years after the Paris Agreement, a special report from the IPCC spelled out how limiting global warming to 1.5C rather than 2C could, among other things, save coral reefs from total devastation, stem rapid glacier loss and keep an extra 420 million people from being exposed to extreme heatwaves.)

Following this, the advisory opinion also makes it clear that countries are not just encouraged – but “obliged” – to put forward climate plans that “reflect the[ir] highest possible ambition” to make an “adequate contribution” to limiting global warming to 1.5C.

(The climate plans that countries submit to the UN under the Paris Agreement are known as “nationally determined contributions” or “NDCs”.)

Moreover, contrary to the arguments of some countries, the advisory opinion states:

“The court considers that the discretion of parties in the preparation of their NDCs is limited.

“As such, in the exercise of their discretion, parties are obliged to exercise due diligence and ensure that their NDCs fulfil their obligations under the Paris Agreement and, thus, when taken together, are capable of achieving the temperature goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C.”

Dr Bill Hare, a veteran climate scientist and CEO of research group Climate Analytics, noted that the court’s stipulations on the 1.5C and NDCs represent a “fundamental set of findings”. In a statement, he said:

“The ICJ finds that the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit is the primary goal because of the urgent and existential threat of climate change and that this requires all countries to work together towards the highest possible ambition to limit warming to this level.

“All countries have an obligation to put forward the highest possible ambition in their NDCs that represent a progression over previous NDCs; it is not acceptable to put forward a weak NDC that does not align with 1.5C.

“The ICJ points to potential for serious legal consequences under customary international law if countries do not put forward targets aligned to 1.5C.”

The court also notes that the concept of equity is essential to the Paris Agreement and other climate legal frameworks, commonly referred to by text noting that countries have “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”.

Significantly, it adds that the Paris Agreement differs from other climate frameworks by also stating that these responsibilities and capabilities should be considered “in the light of different national circumstances”.

The advisory opinion continues:

“In the view of the court, the additional phrase does not change the core of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities; rather, it adds nuance to the principle by recognising that the status of a state as developed or developing is not static. It depends on an assessment of the current circumstances of the state concerned.”

The verdict comes after debate – considered highly controversial by many – about whether “emerging” economies, such as China and India, should be considered “developing countries” at climate summits.

One of the most eye-catching paragraphs of the advisory opinion relates to its verdict on fossil fuels.

In a section labelled “determination of state responsibility in the climate change context”, the court specifically addresses countries’ obligations when it comes to producing, using and economically supporting fossil fuels. (See below).

The court says that fossil-fuel production, consumption, the granting of exploration licences or the provision of subsidies “may constitute an internationally wrongful act” attributable to the state or states involved.

It comes after multiple analyses have concluded that any new oil and gas projects globally would be “incompatible” with limiting global warming to 1.5C.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, climate law expert Prof Jorge Viñuales notes that the clear mention of fossil fuels comes despite not being featured in the questions posed to the court:

“The request characterised the conduct to be assessed by reference to emissions, so the court could have stayed there. Yet, the relevant conduct was expanded to production and consumption of fossil fuels, including subsidies.”

Though the advisory opinion is not legally binding on countries, it could influence domestic decision-making around granting permissions to new fossil fuel projects going forward, adds Joy Reyes, a policy officer at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Litigants can cite the advisory opinion in future climate litigation, which includes the language around fossil fuels. While not legally binding, the advisory opinion carries moral weight and authority, and can influence domestic decision-making around new fossil-fuel projects. If states and corporations fail to transition away from fossil fuels, their risk for liability increases.”

The ICJ’s advisory opinion concludes that nations’ existing maritime zones or statehood would “not necessarily” be compromised by sea-level rise resulting from climate change.

This has long been an important issue for island nations, including the Pacific states that pushed for the court’s advisory opinion (See: How did this case come about?).

Some of these nations are very low-lying and are already making preparations for a time when much of their territory is underwater.

They have been seeking assurances that they will retain territorial rights as the impacts of climate change worsen.

In its assessment of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the ICJ says that nations are “under no obligation to update charts or lists of geographical co-ordinates” due to sea-level rise.

This means the legal rights of states over their maritime zones – including any resources, such as minerals and fish, that are present there – would be protected.

The ICJ also states that, in its view:

“Once a state is established, the disappearance of one of its constituent elements would not necessarily entail the loss of its statehood.”

Prof Viñuales, who acted for the island nation of Vanuatu in the case, tells Carbon Brief this outcome is a “key aspect” of the opinion, adding that it is “remarkable”.

Following the landmark advisory opinion, one of the biggest questions moving forward is what it could mean for other climate lawsuits, both domestic and international.

Advisory opinions from the ICJ are not legally binding, but the court’s summarisation of existing law carries “moral weight and authority”, according to Joy Reyes, a policy officer at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

This is particularly relevant for states that “accept the persuasive authority of international law”, explains Dr Joana Setzer, an environmental lawyer and an associate professorial research fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science’s Grantham Institute.

Courts in some states, such as the UK, Australia and Canada, will consult international law when interpreting domestic laws or dealing with international treaties.

Setzer explains to Carbon Brief:

“The ICJ confirms that failures to act – such as maintaining inadequate national targets, licensing new fossil fuel projects or failing to support adaptation in vulnerable countries – can engage state responsibility under international law. The court also dismissed a common defence – that a state’s emissions are ‘too small to matter’. Even small contributors can be held responsible for their share of the harm.

“Domestic climate litigation may seek to use this argument and the court’s opinion to establish greater obligation on states to address climate change at the domestic level. Courts in jurisdictions that accept the persuasive authority of international law, such as the Netherlands, could now cite this ruling in support of decisions compelling stronger climate action from governments or corporations.”

She adds that the court’s conclusion that “states are not only responsible for reducing their own emissions”, but “also have a due diligence duty to regulate private actors under their jurisdiction” could have implications. Stezer continues:

“That includes fossil-fuel companies. This has far-reaching implications: it signals that states could be in breach if they fail to control emissions from companies they license, subsidise or oversee. This will place greater pressure on states to halt any new fossil fuel projects and introduce stricter regulations on the sector.”

Climate law expert Prof Jorge Viñuales says that the opinion makes it clear that the Paris Agreement is a “serious legal instrument imposing genuine and justiciable obligations”, which is likely to have an impact on domestic lawsuits. He tells Carbon Brief:

“We can expect that to be widely litigated around the world.”

In addition, he says that the court’s opinion that countries’ legal obligations extend beyond the UN climate treaties creates a “much wider chessboard for climate litigation”. He adds:

“Last, but absolutely not least, it was important, from a climate justice perspective, to hear from the court that one cannot simply game the climate change regime without legal consequences. Those consequences may take time to materialise, but they very likely will.”

The ICJ’s advisory opinion was welcomed by many governments, NGOs and legal experts as a “groundbreaking” legal milestone and a “moral reckoning”.

However, the European Commission and France were among those responding to the court’s opinion more cautiously, while opposition politicians in the UK were hostile to the ICJ’s findings.

A Chinese government spokesperson, meanwhile, said the opinion was in line with China’s views, while the White House said the US would put itself and its interests first.

One particularly positive response came from Ralph Regenvanu, minister of climate change adaptation, meteorology and geo-hazards, energy, environment and disaster management for the Republic of Vanuatu, who commended the opinion. In a statement, he said:

“The ICJ ruling marks an important milestone in the fight for climate justice. We now have a common foundation based on the rule of law, releasing us from the limitations of individual nations’ political interests that have dominated climate action. This moment will drive stronger action and accountability to protect our planet and peoples.

Vishal Prashad, director of Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change, welcomed the ICJ’s statements on what he said was the need to “urgently phase out fossil fuels…because they are no longer tenable”. He continued:

“For small island states, communities in the Pacific, young people and future generations, this opinion is a lifeline and an opportunity to protect what we hold dear and love. I am convinced now that there is hope and that we can return to our communities saying the same. Today is historic for climate justice and we are one step closer to realising this.”

The reaction from developed countries was more muted, with France stating that the “landmark opinion will be studied very closely”. It reaffirmed its “unwavering commitment to the ICJ”.

A spokesperson for the European Commission, Anna-Kaisa Itkonen, told the media that the opinion “confirms the magnitude of the challenge we face and the importance of climate action”. She added that the commission would examine what the opinion “precisely implies” and noted that the EU’s emissions are behind those of China, the US and India.

A spokesperson for China’s foreign ministry said in a regular press conference that the ICJ opinion was “of positive significance to maintaining and advancing international climate cooperation”.

They added that, in their view, the court reinforced the “long-standing stance” of China, whereby developed countries should “take the lead” in tackling climate change:

“We noted that the ICJ’s advisory opinion pointed out that the UNFCCC system is the principal legal instruments regulating the international response to the global problem of climate change and confirmed that the principle of common but differentiated responsibility, the principle of sustainable development and the principle of equity are applicable as guiding principles for the interpretation and application of relevant international law.”

In response to the opinion, a spokesperson for the White House told Reuters:

“As always, President Trump and the entire administration is committed to putting America first and prioritising the interests of everyday Americans.”

Many within the wider international community also welcomed the advisory opinion. For example, Mary Robinson, a member of the Elders and the first woman president of Ireland and former UN high commissioner for human rights, called the opinion a “powerful new tool to protect people from the devastating impacts of the climate crisis – and to deliver justice for the harm their emissions have already caused”.

António Guterres, secretary-general of the UN said in a statement that the ICJ had issued a “historic” opinion. He added:

“They made clear that all States are obligated under international law to protect the global climate system. This is a victory for our planet, for climate justice and for the power of young people to make a difference. Young Pacific Islanders initiated this call for humanity to the world. And the world must respond.”

Charities such as Amnesty International, Earthjustice and Greenpeace hailed the “landmark moment for climate justice and accountability”.

Tasneem Essop, executive director of Climate Action Network International, said that “the era of impunity is over”, adding that the ruling “could not have come at a better time” ahead of the upcoming COP30 summit.

Within the media, a lot of coverage focused on the potential that nations might have to pay reparations for breaching their climate obligations.

In the Guardian, Harj Narulla, barrister and leading global expert on climate litigation at Doughty Street Chambers and the University of Oxford, discusses what the ICJ’s advisory opinion could mean for Australia and other major polluters in a “new era of climate reparations”.

In its news coverage, the Daily Telegraph says that the UN “has opened the door to Britain being sued over its historic contribution to climate change”. It adds that the opposition Conservative and Reform parties “both rejected the ruling”.

Maine is sprinting to build clean energy projects before federal tax credits expire.

State utility regulators are fast-tracking plans to procure nearly 1,600 gigawatt-hours of renewable energy, with the goal of getting projects started before key incentives disappear under the budget law signed by President Donald Trump this month. Developers were given just two weeks to submit proposals, with a deadline of July 25.

These projects should help the state make up for clean-energy developments derailed by the pandemic, and ultimately progress toward its newly mandated target of 100% clean energy by 2040.

“This is an opportunity to get some things done that Maine had every intention of getting done a handful of years ago,” said Eliza Donoghue, executive director of the Maine Renewable Energy Association, a nonprofit industry group. “It’s good news.”

The move comes as the clean-energy industry pushes other states, including New York and California, to help speed up wind and solar deployments before subsidies expire in the coming years.

For its part, Maine is looking for enough bids to meet roughly 13% of its annual electricity usage. Preference will be given to developments that make use of property contaminated by toxic PFAS, following the discovery in recent years that at least 60 Maine farms have unsafe levels of these “forever chemicals” in their soil and water.

This specification is a win for renewable energy, wildlife, and farmers whose land has been rendered unusable for agriculture, said Francesca Gundrum, director of advocacy for Maine Audubon.

“This work to help deploy solar and other renewable technologies is exactly the kind of siting we need to see more of in Maine,” she said. “Whatever we can do to minimize the turnover of habitat is something we’re going to be supportive of.”

The current procurement has its roots in a bill the Maine Legislature passed in 2023, calling for the state to source renewable energy from installations sited on PFAS-contaminated land. A request for proposals was issued in August 2024, but none of the initial bids were deemed cost-effective, and none were selected. This year, the Legislature went back to the drawing board, tweaking details about how solar and storage projects can enter proposals.

The amended bill was enacted in June with an “emergency preamble,” allowing it to become law immediately, rather than waiting the typical 90 days after the legislative session adjourns. That move required the approval of at least two-thirds of lawmakers in both the state Senate and House, which is an encouraging sign of support for renewables across political divides, said Dan Burgess, director of the Maine Governor’s Energy Office.

“It’s really exciting that a bipartisan coalition of legislators sees this as an opportunity to bring on low-cost clean energy in Maine,” he said.

Previous renewable energy procurements in 2020 and 2021 chose 24 wind and solar developments to buy power from. Many of these projects, however, fell apart when the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted global supply chains and drove up inflation, Burgess said. This latest solicitation is a great opportunity to make up some of that lost ground, he said.

Maine was an assertive early adopter of the “renewable portfolio standard,” a state-level regulation that requires utilities to obtain a certain percentage of their power supply from renewable resources. When Maine adopted the policy in 1999, it required 30% of the electricity sold to be renewable (a number it hit immediately because of the high concentration of hydropower in the state). The total requirement increases over the years; the state is now aiming for 90% renewables by 2040 with the final 10% coming from non-emitting but not necessarily renewable sources, like nuclear.

Today, about 32% of Maine’s electricity comes from gas-fired power plants, and another 31% from hydropower. Solar and wind together contribute roughly one-quarter of the supply.

Studies suggest that Maine’s commitment to renewable energy has already saved residents significant sums and stands to create even more financial benefits. A 2024 report on the impact of the renewable portfolio standard found that utility customers saved a total of about $21.5 million each year from 2011 to 2022. An analysis released in January concluded that reaching 100% clean energy by 2040 would save the average Maine household around $1,300 per year.

The current procurement is to be the last under the existing regulatory structure, in which the state Public Utilities Commission is the body that runs such solicitations. Legislation signed this month will create a cabinet-level energy department — currently Maine has only an energy office — with the authority to run regular procurements as needed to advance the state’s renewable energy goals.

“Instead of doing these one-off procurements specifically directed by the Legislature, we’re now getting to have that predictability,” Donoghue said.

Southern California’s grid needed help in the fall of 2016. The region was still reeling from the calamitous Aliso Canyon gas leak, and its power plants faced a potential shortfall of that fuel to meet air-conditioning demand when the next summer rolled around. The state took a chance on a new grid technology, lithium-ion batteries, to fill in the gaps.

Big names like Tesla and AES stepped in to help, installing storage at record speed, but so did a little-known firm called Powin. Joseph Lu had founded the Oregon-based company years earlier to import consumer products from China and Taiwan. Sensing a new business opportunity, Powin won a bid and installed 2 megawatts of batteries in a warehouse it owned in Orange County.

This proved to be a launchpad for the firm, which rose to the upper echelons of the booming U.S. battery industry before crashing down to earth last month.

After that Orange County installation, Powin refocused on importing battery cells from China and integrating them into grid storage systems, fully packaged with inverters, controls, and safety systems. Powin went on to deliver battery enclosures for many pathbreaking projects: It supplied the first utility-scale battery in Mexico, a landmark utility-endorsed battery fleet in Arizona, and a truly mammoth system in Australia, to name just a few of Powin’s self-reported 11.3 gigawatt-hours of installed systems. It raised some major outside equity rounds to keep growing and last fall obtained a $200 million debt facility from investment giant KKR.

And then in June, Powin filed for bankruptcy, alerting the state of Oregon of mass layoffs at its Tualatin campus, outside Portland. The news jolted the storage industry, since so many major grid storage plants run on Powin’s hardware and software. The bankruptcy proceedings are ongoing, but storage software specialist FlexGen has placed a bid to buy Powin’s assets at auction in early August, offering Powin customers a way to keep their batteries running.

Cleantech bankruptcies have flourished under the second Trump presidency, and the storage sector is uniquely exposed. The industry runs almost entirely on imported battery cells from China, making it vulnerable to rapidly shifting trade policies. The Biden administration raised tariffs on Chinese batteries, and President Donald Trump cranked the overall rate on Chinese imports as high as 145% in April, though he has altered the rate repeatedly in the opening months of his presidency. Trump’s budget law preserved tax credits for installing grid batteries but added a new bureaucratic regime to regulate the amount of China-derived equipment in those storage plants.

“The business model of integrating batteries into a full storage system is one of these classic high-volume, low-margin businesses,” said Pavel Molchanov, a Raymond James analyst covering cleantech companies. “Margins were low even before Trump and these new tariffs on China, and now it’s a safe bet that their margins have been squeezed even further.”

Nonetheless, Powin’s collapse stands out for the scale of the company’s reach — and raises serious questions. Is Trumpian chaos enough to unseat a leading battery supplier, even as the market for grid batteries continues to surge? Or did Powin’s leadership make choices that ultimately led to its early demise? And perhaps more important, what’s going to happen to those 11.3 gigawatt-hours Powin installed before it went bankrupt?

Powin got to the big leagues by spotting technological trends before they hit the energy-storage mainstream.

That started with the rapid-fire California installations in 2016, when hardly anyone was building large-scale storage. At the time, American developers looked to a handful of Tier 1 battery suppliers, like LG, Samsung, and Panasonic. Powin instead scoured China for manufacturers that American buyers hadn’t discovered yet but that could match key quality metrics. Powin signed an early supply deal with a firm called Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., or CATL, which has since become far better known in the West as the world’s largest battery maker.

Powin also focused on the then-lesser-known lithium ferrous phosphate (LFP) chemistry, which executives hailed as safer and longer-lasting than the mainstream nickel-based chemistries handed down from the electric vehicle supply chain. Powin imported these LFP cells from trusted vendors in China, installed them in engineered metal cabinets in Tualatin, then delivered them to project sites across the U.S. and, later, the world.

By the 2020s, U.S. storage installations were growing at a shocking rate. To keep pace with soaring demand, Powin raised $100 million in February 2021 from investors Trilantic Capital Partners and Energy Impact Partners, followed by $135 million in 2022, led by Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund GIC.

The firm’s first major public setback came when a Powin-supplied battery system in Warwick, New York, burst into flames after a summer storm in 2023. Days later, authorities responded to fumes emerging from another Powin-supplied system in that town.

Developer Convergent Energy and Power owned both systems, and its investigation concluded that a manufacturing flaw in that generation of Powin’s Centipede battery container let water leak in and start electrical fires. Those incidents prompted the Warwick Village Board to freeze local battery development, and they undercut Powin’s reputation for safety, which the company previously had promoted after other companies’ battery fires elsewhere in the country. A spokesperson for Convergent did not respond to requests for comment.

It’s unclear what kind of financial impact the fallout from those fires had on Powin, but the firm subsequently found itself locked in a legal dispute with none other than its longtime supplier, CATL. That company sued Powin in Oregon Circuit Court in December 2024 for $44 million in allegedly unpaid bills, following an earlier arbitration on the matter in Hong Kong.

The circuit court noted in February that Powin “does not deny that they owe money to CATL” and that “it is apparent to the court that the amount of money Powin owes to CATL exceeds the value of the assets Powin holds in Oregon.” That’s not a great sign for a company’s metabolism.

In a subsequent filing, Powin’s lawyers asserted that, actually, CATL was refusing to honor the contracts and instead tried to spring non-contracted price hikes at the last minute: “CATL effectively held Powin hostage to choosing between negotiating a solution with CATL or breaching contracts with its customers.”

In the same suit, the Powin lawyers proposed a nefarious explanation for the souring relationship with CATL, one that sheds light on a broader challenge Powin faced in the maturing storage market.

“Powin finds it highly suspect that the timing of this filing for pre-judgment remedies comes as CATL is aiming to compete directly with Powin to supply complete energy storage systems, moving beyond its historical business model of supplying subcomponents to Powin and others like Powin.”

Powin championed CATL’s battery cells to the U.S. market when buyers still had hang-ups about sourcing high-quality batteries from China. But CATL, recently valued at more than $180 billion, did indeed move beyond simply shipping cells and began competing directly with Powin. CATL launched a containerized storage product in 2023, and in May it rolled out a new 9-megawatt-hour, double-decker grid battery enclosure called TENER Stack.

“The past few months have presented considerable headwinds for system integrators, even without considering company-specific challenges,” said Ravi Manghani, senior director of strategic sourcing at data firm Anza Renewables. “The increasing number of battery [original equipment manufacturers] entering the U.S. market with attractively priced DC blocks and AC solutions has put pressure on the traditional value proposition of system integrators.”

Other sources in the grid storage industry noted that Powin’s quality had suffered in the scale-up, lowering customer interest in its products. The company had always had a smaller balance sheet than competitors like Tesla, Fluence, and Wärtsilä, all of which are publicly traded and worth billions.

Longtime Powin CEO Geoff Brown, who led the company from 2016 through its dynamic growth phase, departed in 2023. He was replaced by Jeff Waters, who touted his leadership at solar panel manufacturer Maxeon during its spin-off from SunPower. Those accolades look less auspicious from today’s standpoint: SunPower went bankrupt last year, and Maxeon’s valuation has tumbled precipitously from its 2023 levels.

Last fall, Powin turned to the credit business at KKR, a private-equity trailblazer famous for record-busting leveraged buyouts like RJR Nabisco in the 1980s and utility TXU in the 2000s.

“The facility will be instrumental in supporting Powin’s working capital needs, driving continued innovation, and further enhancing the company’s financial flexibility as it expands its leadership position in the storage industry,” KKR said in a press release from October announcing the $200 million facility.

It’s a strange thing when a company that just secured ample working capital then runs out of working capital just a few months later. Sources familiar with Powin’s business said the debt package, paradoxically, hastened the company’s demise.

Powin drew on only about $25 million of the available debt, but the deal company leadership accepted was “very ugly” and “poorly structured” for Powin’s purposes, said one former Powin customer granted anonymity to speak on sensitive business matters. Another grid storage veteran, who also spoke on condition of anonymity, likened the situation to a payday loan: “They got upside down, and KKR called it in.”

KKR declined to comment on the specifics of Powin’s debt facility.