Hydrogen has long been a fundamental component in space exploration, serving as a critical fuel for rockets. Its role has been pivotal in missions that have expanded our understanding of the universe, from the historic Apollo moon missions to the latest space endeavors.

Hydrogen's efficiency and thrust capabilities make it an ideal rocket fuel. Its role extends beyond propulsion to powering hydrogen fuel cells that provide electricity and water for astronauts. The environmental benefits of hydrogen, which burns to produce only water vapor, are significant, particularly in comparison to other rocket fuels like methane.

Hydrogen's clean-burning nature underscores its sustainability as a fuel choice. The ongoing development of hydrogen technology not only supports environmental objectives but also drives advancements that benefit other industries. This cross-sectoral impact is evident in projects like MagnaSteyr's collaboration with BMW, which resulted in the BMW Hydrogen 7, a production car powered by hydrogen.

Since the 1950s, NASA has utilized liquid hydrogen as a rocket fuel, capitalizing on its high energy content and efficiency. Notably, the Space Launch System (SLS), designed to carry humans to the Moon and beyond, exemplifies the continued reliance on liquid hydrogen. The SLS's core and in-space stages require approximately 730,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen and oxygen, highlighting the fuel's importance in deep space missions.

Handling liquid hydrogen poses challenges due to its low temperatures and high volatility. NASA's efforts in developing zero boil-off technology are crucial in addressing these issues.

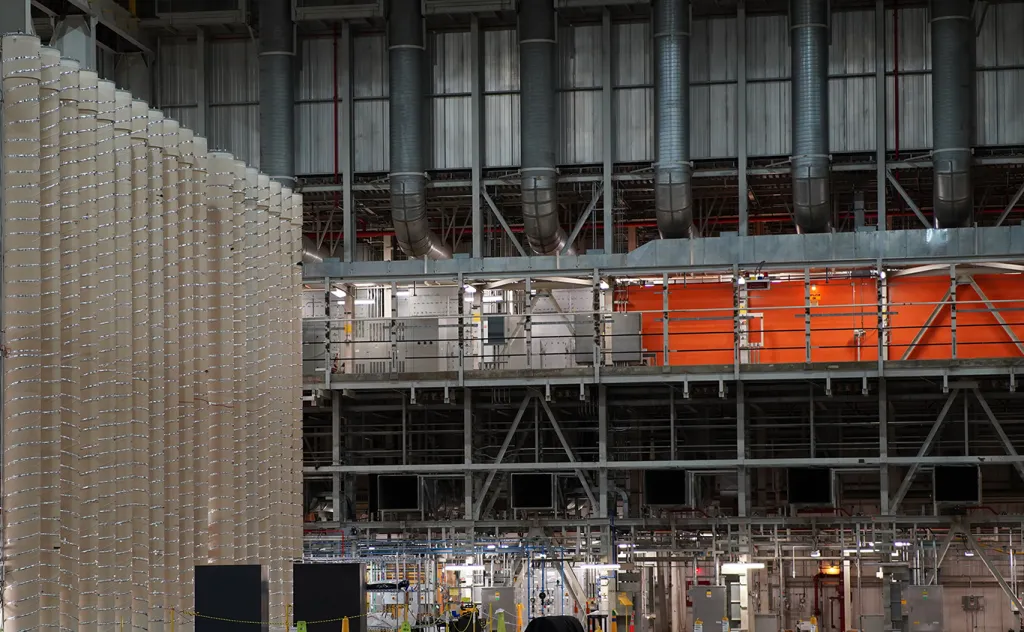

NASA's Kennedy Space Center has made significant progress in this area, constructing the world's largest liquid hydrogen storage tank to support the SLS rocket. This tank, capable of holding 1.4 million gallons, demonstrates a substantial advancement from the storage technologies used during the Apollo and Space Shuttle programs. The innovative design aims to enhance efficiency and reduce the time between multiple launch attempts.

Moreover, advancements in hydrogen storage and handling, as seen in the aerospace industry, have applications beyond space exploration, potentially revolutionizing sectors like automotive. For instance, Austrian manufacturer MagnaSteyr has adapted technology from the Ariane rocket program to build clean-burning hydrogen cars.

Liquid hydrogen continues to play a vital role in space exploration, with ongoing technological advancements enhancing its efficiency and sustainability. As we look toward future space missions, hydrogen's importance in achieving deeper space exploration and its broader environmental and technological impacts cannot be overstated.

The concrete industry, a significant contributor to global CO2 emissions, is at the forefront of a green transformation. The shift towards hydrogen, as highlighted in recent research and industry practices, is a necessary step in reducing the environmental impact of concrete production.

Traditional cement production relies on fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas, leading to substantial CO2 emissions. Recent studies suggest that substituting these instead with hydrogen, which combusts to form only water vapor, can substantially reduce emissions. This innovative approach involves replacing traditional energy sources with hydrogen in cement kilns, promising a significant reduction in carbon footprint while enhancing the energy efficiency of the production cycle.

Developments, such as the VDZ's roadmap in Germany, integrating up to 10% hydrogen into the fuel mix, and by 2050 targeting a net-zero CO2 cement production. This initiative highlights the industry's commitment to sustainability and the pivotal role of hydrogen in achieving these goals.

A groundbreaking example is the Fuel Switching Project at Hanson's Ribblesdale plant in the UK, funded by the British Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. This project explored the use of 100% net-zero fuels, including hydrogen, maintaining the clinker and cement quality. These trials proved the technical viability of hydrogen in large volumes without significant changes to the production process, marking a significant step towards sustainable cement manufacturing.

The production of clinker, a key ingredient in cement, is a major source of emissions. Introducing hydrogen as a reducing agent in the clinker formulation can cut down the clinker requirement by half, thereby curbing CO2 emissions considerably. Research into alternative cements and the role of hydrogen in enhancing their production is ongoing.

A groundbreaking application of hydrogen in cement production involves its use in capturing and repurposing CO2 emissions. This method converts the captured carbon into valuable commodities like alternative building materials or synthetic fuels.

Producing green hydrogen, derived from renewable sources, is initially more expensive than traditional methods. However, as renewable energy becomes more affordable, green hydrogen’s feasibility improves, offering a sustainable solution for the cement industry.

The integration of hydrogen into concrete production is in its early stages, with ongoing pilot projects and studies. Key challenges include the expense and availability of green hydrogen and the need to modestly update existing infrastructure to adapt to hydrogen-based technology.

Expanding hydrogen production, storage, and transportation infrastructure is crucial for its large-scale application in the cement industry. This requires substantial infrastructure investment and development.

The concrete industry is on the cusp of a sustainable revolution, with hydrogen poised to be a key player in reducing its environmental impact. Continued research and investment in this field are crucial for harnessing hydrogen’s full potential in creating eco-friendlier construction materials.

The transportation sector, a major contributor to global CO2 emissions, is witnessing a transformative shift with hydrogen emerging as a promising alternative fuel. Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) mark a pivotal advancement towards sustainable and emission-free transportation. By harnessing hydrogen to generate electricity using fuel cells, these vehicles power electric drive systems and emit only water vapor, positioning them as an eco-friendly alternative to conventional internal combustion engines and a viable complement to battery electric vehicles (EVs).

Hydrogen FCVs are like battery electric cars, but they make their own electricity using hydrogen instead of only using battery storage. Models like the Toyota Mirai and Hyundai Nexo are showing us how this can work. You fill them up with hydrogen gas, and off you go – without harming the environment.

Hydrogen-powered FCVs excel in scenarios where extended range and rapid refueling are paramount, such as in long-haul, heavy-duty transportation where battery efficiency may falter. They offer significant benefits over traditional vehicles, including extended driving ranges, quick refueling times akin to conventional vehicles, and superior payload capacities - essential for larger transport applications.

The proliferation of hydrogen FCVs hinges on establishing a comprehensive hydrogen infrastructure. Efforts like the U.S. Department of Energy's $7 billion initiative to create clean hydrogen hubs are pivotal. These initiatives, along with significant backing from legislation such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, are crucial in promoting hydrogen fuel cell technology and supporting infrastructure development.

However, challenges remain, particularly in constructing an extensive hydrogen refueling network critical for FCVs' widespread adoption. This is being addressed globally, with countries like Germany and Japan actively enhancing their hydrogen refueling infrastructure. Recent initiatives in the United States are starting to create hydrogen refueling corridors for heavy vehicles along selected national highways. These corridors provide access to any location within 200 miles or more on either side of the national highway.

To fully leverage hydrogen FCVs' potential, several key challenges must be addressed:

Expansion of the hydrogen pipeline network is imperative to facilitate efficient hydrogen delivery from production sites to consumers. Developing safe and efficient transport methods and connective infrastructure is essential.

To compete with current transportation fuels, hydrogen fuel cell technologies must achieve cost-effectiveness, enhanced durability, and improved performance. Innovations in liquid hydrogen storage and fueling technologies are critical, especially for medium- and heavy-duty transport.

Clear regulatory guidelines are needed to oversee the infrastructure for hydrogen production, transport, and storage. Establishing the roles of regulatory bodies like the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in overseeing hydrogen-related infrastructure is crucial. The state of California has implemented and in operation several examples of hydrogen infrastructure regulation and promotion.

With ongoing investments and research, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are poised to significantly contribute to emission reduction in transportation. Advancements in hydrogen utilization components and systems, combined with supportive policies and international collaboration, are key to harnessing hydrogen's full potential in this sector.

The prospect of hydrogen as a vehicle fuel is increasingly optimistic. Advancements in hydrogen production, storage, and distribution, coupled with conducive policies, indicate that FCVs increasingly common in California could soon be a familiar sight on major highways nationally. This transition not only aids in reducing greenhouse gas emissions but also diversifies our transportation energy sources.

Insights from the International Energy Agency's Global Hydrogen Review and analyses by Reuters highlight the current state and future potential of hydrogen in vehicle fuel production. These reports stress the importance of targeted efforts to expand hydrogen supply and demand, leveraging existing industries and infrastructure. As the hydrogen sector evolves, it's poised to play a crucial role in clean energy transitions, addressing key energy challenges.

The landscape of electricity generation is evolving. Utilizing hydrogen in fuel cells and power plants, especially gas turbines, represents a significant shift towards cleaner energy solutions.

Fuel cells, leveraging the reaction between hydrogen and oxygen, produce electricity with water as the sole byproduct, exemplifying a truly zero-emission technology. The hydrogen used is increasingly sourced from green production methods like electrolysis, powered by renewable sources such as solar and wind energy, marking a critical step in reducing the environmental impact.

Hydrogen's role in power generation showcases its versatility and potential as a key player in the transition to clean energy. Its application in gas turbines and fuel cells is particularly noteworthy. These technologies leverage hydrogen's high energy content to produce electricity while emitting only water vapor, making them environmentally friendly options. Globally, several initiatives, such as Japan's pioneering gas turbine project, exemplify the practical implementation of hydrogen in power generation. These projects demonstrate not only the feasibility but also the growing reliability of hydrogen as a clean energy source.

Looking to the future, hydrogen's prospects in electricity generation are indeed promising. One of the most significant advantages of hydrogen in this context is its ability to provide effective solutions for grid stability and the storage of renewable energy. This is particularly important for managing the intermittency of renewable sources like wind and solar power. By acting as a storage medium, hydrogen can accumulate excess energy generated during peak production times and release it when demand is high, ensuring a consistent and reliable energy supply.

However, the widespread adoption of hydrogen in the energy sector faces several challenges. One of the main hurdles is the transportation and storage of hydrogen, primarily due to its low energy density compared to traditional fossil fuels. This challenge has spurred innovative solutions, such as the use of ammonia as a hydrogen carrier. Ammonia, with its higher energy density, offers a more efficient way to transport and store hydrogen. Additionally, the conversion process from ammonia back to hydrogen is relatively straightforward, making it a viable option for electricity generation.

In recent years, technological advancements have further improved the viability of ammonia as a hydrogen carrier. For instance, the development of advanced catalytic processes has made the conversion of ammonia back to hydrogen more efficient and environmentally friendly. Moreover, research into novel materials for hydrogen storage, like metal hydrides or advanced composite materials, is paving the way for more compact and safer hydrogen storage solutions.

The integration of hydrogen into existing energy infrastructures is another area of ongoing research. Efforts are being made to adapt existing gas pipelines for hydrogen transportation, which could significantly reduce the costs and environmental impacts associated with building new infrastructure. Additionally, blending hydrogen with natural gas in existing power plants is being explored as a transitional strategy towards a more hydrogen-dominated energy sector.

In summary, hydrogen, particularly green hydrogen produced from renewable energy sources, holds significant promise for transforming the energy landscape. Its ability to provide clean, reliable power, coupled with developments in technology and infrastructure, positions hydrogen as a key contributor to achieving global carbon neutrality goals. The ongoing research and innovations in this field are vital for overcoming the existing challenges and unlocking the full potential of hydrogen in the energy sector.

The potential of hydrogen in electricity generation is immense. With advancing technologies and reducing costs, hydrogen stands as a pivotal element in a clean, secure, and affordable energy landscape. The ongoing development and scaling of hydrogen technologies are vital for harnessing this potential, significantly contributing to global energy sustainability and climate goals.

Methanol, a widely used simple alcohol, finds its applications across a range of industries, from manufacturing plastics to pharmaceuticals. Traditionally, methanol is produced through steam reforming of natural gas, a process that generates syngas, which is then converted into methanol. This method, though effective, is significantly carbon-intensive, contributing to CO2 emissions. However, a transformative shift towards sustainability in methanol production is underway, focusing on the integration of green hydrogen.

It's crucial to differentiate between grey, blue, and green methanol. Grey methanol is produced from natural gas or coal, blue methanol includes carbon capture in its production process, and green methanol is created using only renewable energy sources.

Grey methanol is the most commonly produced type. It is made via a synthesis reaction from methane, which is primarily obtained from natural gas or, in some cases like in China, from coal. This production process is not renewable and is linked to significant greenhouse gas emissions, particularly CO2. The reliance on fossil fuels makes it the least environmentally friendly type of methanol.

Blue methanol is also derived from natural gas, similar to grey methanol. However, the key distinction is that the production process of blue methanol includes carbon capture and storage (CCS). The CCS technology captures the larger portion of the CO2 emissions generated during methanol production and stores them, typically underground. This process reduces the carbon footprint of methanol production, making blue methanol less polluting than grey methanol. However, it's important to note that it does not eliminate emissions entirely and still relies on fossil fuels.

Green methanol is produced using only renewable energy sources, ensuring no harmful gases are emitted into the atmosphere during its production.

There are two primary types of green methanol:

Biomethanol is produced from the gasification of sustainable biomass sources, such as agricultural, livestock, forestry residues, and municipal waste. Gasification involves combustion at high temperatures (between 700 and 1,500 ºC), transforming the combustion gases from these materials together with green hydrogen into green methanol.

”eMethanol” is produced from hydrogen generated from renewable electricity (green hydrogen) and captured carbon dioxide. The process of creating green hydrogen involves electrolysis, where electric current is used to separate hydrogen from oxygen in water. When this electricity is sourced from renewables like wind or solar farms, it results in a clean energy process.

The transition to blue and particularly green methanol is pivotal in decarbonization efforts and aligns with global sustainability goals, significantly reducing the chemical industry's carbon footprint.

The incorporation of green hydrogen, produced via water electrolysis powered by renewable energy sources, is revolutionizing methanol production. This innovative approach, known as green methanol (eMethanol) production, drastically cuts the carbon footprint associated with methanol manufacturing, aligning with global climate change mitigation efforts.

Innovative projects in countries like Denmark are exploring green methanol production from biogas. This process involves splitting biogas into CO and H2 using an electrically driven catalytic converter, supplemented with additional hydrogen from electrolysis, to create eMethanol. Such techniques are proving to be economically competitive, particularly under carbon taxation regimes. Additionally, global investments, notably in China and India, underscore the strategic importance of hydrogen in energy sectors, heralding a shift towards green hydrogen in various industries, including eMethanol production.

The production of eMethanol on an industrial scale offers a promising solution to storing renewable energy. It aids in reducing emissions during the transition to electric mobility and provides carbon-neutral mobility options. With countries increasingly aiming to limit or ban internal combustion engines, eMethanol offers a viable alternative. Pilot plants, particularly in Iceland, have demonstrated the feasibility of this approach. Companies like Siemens Energy are developing "Power to X" solutions, highlighting the maturity and readiness of the required technologies.

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) posits that renewable eMethanol could become cost-competitive by 2050 with targeted policies. Key strategies include systemic investment in technology and infrastructure and policy reforms to level the playing field for renewable methanol.

The integration of green hydrogen into production of eMethanol marks a critical step towards more sustainable industrial processes.

The following commentary was written by Larry Glover, a Maryland-based energy marketing & communications subject matter expert and community engagement specialist. See our commentary guidelines for more information.

We just lived through the hottest summer in recorded human history. From coast to coast, the United States set heat records, the brunt of which underserved communities felt the most.

One thing we were fortunate enough not to experience this time were rolling blackouts due to energy shortfalls. But we came close. In Texas, for example, rooftop solar helped keep the state’s grid online during the hottest summer on record.

Despite its benefits, the real value of rooftop solar isn’t always acknowledged as a solution to climate change and the needs of our electricity grid. We have seen some states take the lead, but we must act quickly to leverage resources to benefit underserved communities.

As climate disasters become more normal, our state and national grids will be tested more often. We can resolve this sad reality, however. Ensuring our nation’s clean energy movement is both inclusive and empowering has never been more important.

Here’s what I believe: Rooftop solar and batteries have a proven track record to deliver economic, community, and environmental benefits to everyone – and have the potential to positively impact our entire grid distribution for the better.

Not only are individual rooftop solar and battery systems critical for our clean energy future, but this technology can be connected and serve as a massive, distributed, power plant. Called a Virtual Power Plant (VPP), these networked systems can help bring value and grid stability and contribute to our clean air goals by reducing CO2 emissions.

For example, ConnectedSolutions has solar and battery system programs in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. The goal is to lower grid costs for all residents. Replicable programs such as these make it easier for home and small businesses to share their clean electrons when the grid needs it most, bolster climate and clean energy goals and help to mitigate unnecessary costs to grid infrastructure.

If we take the best of what we know and apply it to low-income and underserved communities, we can create energy solutions with enormous benefit to the communities that need it most. Harnessing the benefits of VPPs and connecting rooftop solar and batteries will deliver benefits with far greater impact than any of those initiatives applied individually. Bills introduced in Michigan this year (HB 4840 and HB 4839) proposed not only to create a virtual power plant, but also provide additional, targeted incentives to get batteries into the low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities that have experienced the most severe impacts of power outages.

In 2022, more than 140 million people across the US were impacted by either rolling blackouts or calls to conserve power due to extreme weather. The proven reliability of local solar and batteries is paramount to ensuring that all of our communities stay safe.

Building virtual power plants in LMI communities offers immense potential for positive change. In fact, the Department of Energy recently just released a new report about the benefits of VPPs, and they found that tripling VPP capacity from 80 gigawatts to 160 gigawatts by 2030 could save ratepayers $10 billion per year in grid costs. Earlier this year, Brattle released a report that found that VPPs could save utilities $15-$35 billion in capacity investments over the next 10 years. Regardless of which study turns out to be accurate, the opportunity before us is immense. It can provide reliable and affordable electricity access while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. We should easily conclude that rooftop solar is a necessary element in the energy solution for communities.

There is a risk, however, that these innovative solutions may inadvertently exacerbate existing inequities if not implemented with careful consideration. The first step is ensuring equal access to virtual power plant programs. This means providing opportunities for participation regardless of income level or location. By doing so, we can avoid creating a situation where only certain privileged individuals or communities can benefit from these advancements in energy technology.

It is imperative that we address equity concerns to ensure that all community members can reap the benefits of virtual power plants. Ensuring equitable access is crucial in creating a sustainable and inclusive energy future for LMI communities. Virtual power plants have the potential to revolutionize our energy systems by enabling decentralized generation and distribution of electricity.

It is important to consider the specific needs and challenges faced by marginalized communities. By actively involving communities in the planning and implementation processes, we ensure that their voices are heard, and their unique circumstances are considered.

The benefits of implementing virtual power plants with rooftop solar and batteries in LMI communities is a game changer. How else can we address energy affordability, grid reliability, reduced energy costs, job creation and community empowerment all within one focused initiative. We know it comes with its challenges and obstacles. However, as we search for long term solutions that prepare all communities for the great energy transition this is surely a way to leave no community behind.

Like it or not, the next presidential election is just a year away. And while President Biden is sure to campaign on the Inflation Reduction Act, it may not win him too many voters — because they don’t know much about it.

In a Washington Post-University of Maryland poll from July, more than two-thirds of Americans said they hadn’t heard about new tax credits incentivizing solar panel, electric vehicle and heat pump purchases passed under the IRA — even though a majority said they’d support these things. Nearly three-quarters hadn’t heard of the IRA at all.

Another newer poll from data sciences firm BlueLabs Analytics had similar results, finding that 40% of all Americans say they know nothing about federal subsidies for electric vehicle purchases.

Whether residents know it or not, the IRA is bringing big investments to the swing states Biden will try to win over next year, E&E News reports. In Georgia, electric vehicle and solar panel manufacturing is taking off with backing from the IRA and support from the state’s Republican governor. Michigan and North Carolina are likewise seeing a surge of new electric vehicle investments.

But as advocates and officials tell E&E News, Biden and his allies have a lot more work to do if they want voters to know how those investments came about.

🚗UAW reaches milestone deal: The United Auto Workers reach a tentative deal with General Motors after doing the same with Ford and Stellantis, but it’s unclear how well the agreement will protect workers as electric vehicle sales slow and automakers trim their EV investments. (Inside Climate News, E&E News)

🖊️ Redefining clean energy: As states struggle to meet their own clean electricity goals, some are changing definitions to include nuclear, natural gas and biomass generation. (E&E News)

⚖️ Who’s behind protest criminalization: Fossil fuel companies have spent millions of dollars on lobbying and campaign donations to state lawmakers who’ve enacted laws that penalize protests near pipelines and fossil fuel infrastructure. (Guardian)

🛢️ Captured carbon’s oil-boosting fate: At least 60% of carbon captured annually fossil fuel plants around the U.S. is used to extract more oil through so-called “enhanced oil recovery.” (Washington Post)

🏭 Meet our biggest polluters: Coal and oil power plants top a list of the U.S.’s biggest greenhouse gas polluters last year. (Inside Climate News)

💵 Governments buy clean: Federal and state Buy Clean programs aim to use governments’ massive purchasing power to drive manufacturing of low-carbon steel, cement and other building materials. (Canary Media)

🌎 Climate denier of the House: Newly elected Republican U.S. House Speaker Mike Johnson has a long track record of supporting fossil fuels and denying their contributions to climate change. (The Hill)

🗣️ Scientists speak out: Climate scientists who once stayed out of the public eye are increasingly raising their voices to warn the world of a worsening climate emergency. (Washington Post)

Wisconsin will lose out on millions of federal dollars for electric vehicle charging infrastructure if the state does not pass legislation to allow stores or other owners of EV chargers to bill drivers for the amount of electricity they get when they plug in.

Billing by the kilowatt-hour is a requirement to participate in the federal National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program, which has promised Wisconsin $78.6 million and the chance to apply for a pot of $2.5 billion in competitive funding if it meets the program requirements.

The goal of NEVI is to develop charging corridors along highways, with chargers available every 50 miles.

Advocates are hoping for legislation that would make the change needed for federal funding, by enshrining in law that billing for electricity at an EV charger is allowed and would not make the owner a public utility.

The legislature takes a break from Nov. 16 to January 16, hence advocates say time is of the essence to meet the March 2024 deadline for federal funding.

Legislation allowing billing by the kilowatt-hour was introduced in 2021 but didn’t pass. Advocates say they are expecting Republican state Sen. Howard Marklein to introduce a bill this fall. A spokesperson for Marklein’s office said they expect the bill to be circulated for co-sponsors next week.

“We have a sense of urgency we didn’t have last year,” said Francisco Sayu, director of emerging technology for RENEW Wisconsin. “That limitation on electric vehicle charging stations has slowed down the Wisconsin market. We don’t have as many EV charging providers in the state as we could.”

The Wisconsin Department of Transportation has a plan for deploying charging stations in keeping with the NEVI requirements, but the law change is needed to receive the funds.

Currently in Wisconsin, entities from municipal governments to convenience stores that host chargers can only collect a parking fee or bill for the amount of time a vehicle is plugged in.

“We may be the only state left in jeopardy of losing federal funding for EV corridors,” said Tom Content, executive director of the Citizens Utility Board of Wisconsin (CUB).

The consulting firm EVAdoption reported that in fall 2021, there were 2,251 charging stations in Illinois, 1,226 in Minnesota and 881 in Wisconsin, including level one and two and fast-charging stations. There are 15,700 electric vehicles registered in Wisconsin, compared to 66,880 in Illinois and 24,330 in Minnesota, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Even adjusting for Illinois’ larger population, Wisconsin still lags on both fronts.

Electric vehicle advocates and owners say Wisconsin’s charging network is woefully lacking, making it harder to rely on an electric vehicle in the state.

Corey Singletary, utility analyst for CUB, testified before the Public Service Commission about a road trip he took with his family in their electric Ford 150 Lightning pickup, from Madison to Minneapolis along Interstate 94.

This heavily-traveled corridor proved difficult to traverse with an electric vehicle: at one Electrify America charging station, two out of four chargers were inoperable, there was a half-hour wait for the remaining chargers, and they delivered less power than expected. The family had a similar experience at a different charging station on the return journey.

Singletary’s testimony came in a rate case for Xcel Energy, which is seeking the commission’s permission for its subsidiary Northern States Power Company to operate two fast-charging hubs. Singletary said CUB is in favor of the move. Ideally, he said, the state needs more chargers operated both by utilities and by public and private entities.

“One of the questions is whether or not it’s appropriate for monopoly companies like the public utilities to own and operate EV charging stations,” Singletary said. “There is a concern or belief that utilities will be able to leverage their monopoly position to disadvantage other third parties.”

But since the EV charging market is so nascent, more utility participation could actually jumpstart private investment.

“If things can be provided more efficiently and effectively by a competitive provider, that’s great,” Singletary said. “But right now, there’s not really effective competition in the EV charging space, so the bar is very low. If you allow utilities like Xcel and MGE to kickstart this space and get some utility-owned chargers out there, and if they are all subject to regulation, you set a minimum bar for everyone else to clear, and that helps all consumers.”

In a rate case before the commission, MGE is proposing to change to billing by the kilowatt-hour. Utilities are allowed to bill by the kilowatt-hour without legislation but still need commission approval for changes.

MGE owns 53 EV chargers. That includes 13 DC Fast Chargers – eight of those at a fast-charging hub in downtown Madison – and 40 Level 2 chargers around the area. The utility charges $5 an hour for fast-chargers and $2 an hour for slow chargers.

In testimony before the Public Service Commission, MGE rates director Brian Pennington noted that in 2017 most chargers could deliver about 50 kilowatts, and now many deliver 350 kilowatts.

“This is a seven‐fold increase in power,” Pennington testified. “Likewise, auto manufacturers are increasingly rolling out EV models capable of charging at these higher DC currents. This equates to much more energy being transferred from the grid to the EV’s battery than was possible in previous EV models. Because the MGE public charging tariff has been based on the time spent charging instead of the energy delivered, newer and often more expensive models are able to take advantage of the existing billing structure.”

MGE spokesperson Steve Schultz said that the utility wants to make sure ratepayers who don’t have EVs are not paying unfair amounts to subsidize the utility’s investments in EV charging infrastructure. The current billing model allows vehicles to get a lot of energy for a small fee, and MGE ratepayers are picking up the slack.

“Energy-based public charging will better reflect the costs and benefits of the energy being delivered from the charger to the EV, and thereby reduce cost inequities among customers,” said Schultz.

The EV charging issue in Wisconsin has dovetailed with an ongoing larger debate related to utilities protecting their turf as the energy landscape shifts.

Wisconsin utilities have stridently opposed third-party ownership of solar installations, since — they argue — a company owning a solar installation and providing the energy to the homeowner, church, municipal agency or other entity means the developer is acting like a utility. Solar advocates have long asked the legislature, the Public Service Commission and the courts to provide clarity on the legality of third-party ownership of rooftop solar, so far to no avail.

Meanwhile a bill that would allow third-party ownership of community solar is pending in the legislature.

Utilities have similarly argued that a government or business charging by the kilowatt-hour at EV chargers means they are acting like a utility, selling electricity. That issue and the fact that charging a set fee is likely less lucrative makes it relatively unattractive for companies to develop EV chargers in the state.

“It’s a very risky proposition to come to Wisconsin and risk being labeled a public utility,” said Sayu. “If I was a private investor looking to get into EV charging, I wouldn’t want to run the risk of becoming a public utility. Basically we just want an exception for EV charging, that you can sell electricity to the public [through chargers] without being regulated as a public utility, and that’s it.”

Utilities still stand to benefit from privately-run EV chargers in their territory, since the entity running the charger ultimately needs to buy their electricity from the utility.

Previously, utilities pushed for proposed legislation to ban EV charging hubs powered by on-site renewable energy, since that could disconnect them completely from the utility. This provision was unpopular with clean energy advocates.

Sayu said that realistically an off-grid, renewable-powered EV charging station would not be a good financial proposition, and developers are unlikely to undertake such projects. Among other issues, NEVI funding requires that four vehicles be able to charge at once.

“In order to do that from an off-grid EV charging station you’d have to have a significant amount of solar or wind and a significant amount of storage,” Sayu said. “If you were to build one of those stations today attached to the grid, you’re looking at spending between $700,000 to a million dollars. If you did it off-grid, you’re looking at $15-17 million. No one would build that in a state that has less than 1% EVs.”

In other states, non-utility entities that operate charging stations generally can set their own prices.

“Companies like EVGo and Electrify America have moved away from postage stamp pricing where all rates are the same, making it more locational,” said Singletary. “There is a move in the EV charging industry to have rates more reflective of cost of providing electricity to a particular charging station.”

Such entities could theoretically charge different rates based on time of day too, to encourage charging at low-demand times, which could be seen as “economics 101,” Singletary said.

But “if you are using a DC fast charger on a road trip to Chicago or Minneapolis, you really don’t have a choice — you need to charge when you need to charge,” hence a time-of-day rate would not be an incentive.

“Now in the state of Wisconsin we don’t even have that opportunity to engage in that discussion,” Singletary said, “because everyone but public utilities is relegated to charging essentially a parking fee.”

Correction: Francisco Sayu of Renew Wisconsin estimated that building an off-grid electric vehicle charging station would cost between $15 million and $17 million. A previous version of this story misquoted the number.

This story was originally published by Mountain State Spotlight. Get stories like this delivered to your email inbox once a week; sign up for the free newsletter at https://mountainstatespotlight.org/newsletter.

WEST UNION — Nearly 20 years ago, Cindy Dotson bought more than 200 acres of farmland and forest in her native Doddridge County. The property is beautiful — but there’s one part Dotson doesn’t care for. At one end sits a massive, yellow tank painted with a bygone advertisement: an eye sore that renders the section of property mostly useless.

The ten-foot above-ground storage tank, accompanied by an underground oil or gas well and guarded by barbed wire and wooden stakes, is just one of the thousands of orphaned oil and gas wells littered across the state.

With no living mineral rights owner and no existing operator, the oil tank and well have sat untouched on Dotson’s property for the last 15 years. She’s concerned about its proximity to a creek, where cattle used to drink. And now, she leases the land to tenants who share those concerns.

“We would just like it to be plugged so that we can reclaim this property, and we never have to worry about anything leaking out of it,” Dotson said. At times, she says she sees a film she thought was oil leaking at the base of the tank but has never been able to confirm it.

But unless she shells out the cash herself, the well will remain a concern for Dotson until the state gets around to plugging it.

Both orphaned and abandoned wells no longer produce oil or gas. But abandoned wells still have a solvent owner, while orphaned wells don’t — either because the company went out of business or there is no existing record of the driller. So here, the responsibility of plugging and remediating these wells falls to the state. And it’s a massive undertaking that West Virginia regulators don’t have many resources to tackle.

Now, the state is getting some help: up to $212 million from the federal government to plug orphaned wells. But even then, for West Virginia, it’s only a drop in the bucket.

Thousands of orphaned wells are littered throughout West Virginia but are most heavily concentrated in Ritchie, Tyler and Doddridge counties. Some date back to the early 20th century, while others are more recent. Some are hazardous and leak large amounts of methane, while others don’t. But all are a result of operators abandoning them after bleeding them dry of their natural resources.

Under West Virginia law, oil and gas companies are responsible for plugging and remediating their wells, and a spokesman for the state Department of Environmental Protection says the agency often pursues enforcement measures. But despite that, wells across the state remain abandoned and unplugged.

Now, this new influx of federal cash from the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law will allocate $4.7 billion to states, tribes, and the Federal Bureau of Land Management in an effort to address some of the damage left by the oil and gas industry, according to the federal Department of the Interior.

The newly established federal program is a key part of the Biden administration’s efforts to curb the release of methane — a greenhouse gas that greatly contributes to global warming. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that the unplugged, non-producing oil and gas wells emitted 275,000 metric tons of methane in 2020; equivalent to emissions of more than 1.7 million gasoline-powered vehicles driven in one year.

West Virginia’s DEP, along with 23 other states, received an initial $25 million grant from the federal program earlier this year, which is the first of three expected rounds of funding the Biden administration is set to award. With that, the state’s Office of Oil and Gas estimates it can plug 202 orphaned wells in West Virginia, which it has decided to outsource to contractors, despite criticism.

Beyond the initial grant, West Virginia is likely to receive a total of $117 million in formula grant funding and has an opportunity to receive an additional $70 million through the performance grant portion of the federal funding — resulting in an overall total of $212 million.

Historically, progress on remediating orphaned wells has been slow. The state used to only be able to afford to plug one or two wells a year. More recently, state lawmakers directed more money to the issue, which enabled the DEP to remediate six wells last fiscal year and 22 this fiscal year, according to spokesman Terry Fletcher.

But the $212 million boost in federal funding will speed up the pace. It could go as far as to help plug roughly 1,700 orphaned wells. However, this would still only be a fraction — about 26% — of the documented orphaned wells scattered across the state.

In reality, the need could be much larger because the exact number of wells isn’t known, largely due to the fact that wells drilled before 1929 were not required to be registered with the state. Because of that, there are tens of thousands of undocumented orphaned oil and gas wells scattered throughout the state, according to the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey. And the state’s current estimates also don’t account for all the thousands of abandoned oil and gas wells that are likely to become orphaned in the future.

“This is just scratching the surface,” said Ted Boettner, a senior researcher at the Ohio River Valley Institute. “That’s just the orphaned wells. There’s another 12,000 abandoned wells and tens of thousands of undocumented orphaned wells in West Virginia.”

Among those undocumented orphaned wells is the one on Dotson’s property.

Dotson maintains the fencing around the giant above-ground storage tank that accompanies the well, fearful of a car hitting it and causing a leak — all she really can do at this point.

The monthly visits by a gathering company to empty the tank stopped years ago when there were no longer any remaining living mineral rights heirs and Dotson couldn’t get anyone else to pump the tank. She even briefly considered plugging the well herself, but the cost was too high to afford.

Now, her frustration is only further exacerbated by the slim chance that any portion of the millions in federal funding the state is getting will go towards the well on her land because of its undocumented status.

“So, again, we can do nothing. We’re stuck,” Dotson said. “So, what is the state doing for these undocumented orphaned wells? If there’s thousands of them, they need to do something about them also.”

As an Ohio uranium enrichment plant opened this month, yet another study questioned whether nuclear power from small modular reactors can compete with other types of electricity generation.

Centrus Energy’s new plant in Piketon produces high-assay, low-enriched uranium, or HALEU. The fuel will contain between 5% and 20% fissile uranium, or U-235, which is the range needed for various types of small modular reactors, or SMRs. The current fleet of large nuclear reactors uses fuel with up to 5% U-235.

Large nuclear plants have had problems competing with other types of electricity generation in recent years. Ohio’s House Bill 6 would have mandated ratepayer spending of more than $1 billion to subsidize the 894-megawatt Davis-Besse plant and 3,758-megawatt Perry plant in Ohio, for example. Lawmakers repealed that law’s nuclear subsidies after alleged corruption came to light.

Now the question is whether small modular reactors designed to produce up to 300 MW of electricity can compete better.

Huge gigawatt-scale nuclear plants can have economies of scale because their power output grows faster than increases in capital and operating expenditures.

“However, the extensive customization of many of the currently deployed reactors undercuts much of that economy,” said William Madia, a nuclear chemist and emeritus professor at Stanford University who is now a member of Centrus’ board of directors.

The lack of a standard design also makes it harder for large reactors to get replacement parts when needed. “Things like large-scale forgings are in short supply globally,” Madia noted.

In contrast, small modular reactors can be built in indoor factories and then sent to where they’ll be used. That avoids site-by-site mobilization costs, as well as weather problems that might interrupt construction.

“But the real driver is standardized design,” Madia said. So eventually, production can take place on assembly lines. And that should produce its own economies.

All in all, “the capital cost for SMRs is much lower than GW-scale machines,” Madia said. Also, if the choice is between lower-cost modular reactors and huge ones, “many, many more utilities can afford a few billion dollars on their balance sheets. Very few can handle $10-plus billion.”

No small modular reactors are operating commercially in the United States yet.

“Right now, if you’re looking to spend money on bringing new generation online, you have tech that you know works with wind and solar and storage,” said Neil Waggoner, federal deputy director for energy campaigns at the Sierra Club.

An analysis published this month by the journal Energy estimated the levelized cost of electricity, or LCOE, for different types of small modular reactors. The LCOE basically reflects the average costs for producing a unit of power over the course of a generation source’s lifetime.

Small modular reactors “seem to be non-competitive when compared to current costs for generating electricity from renewable energy sources,” the Energy study found.

Comparing intermittent resources like wind and solar to “dispatchable resources with small land footprints is a flawed exercise,” said Diane Hughes, vice president of marketing and communications for NuScale Power. Nuclear energy from small reactors requires little new transmission infrastructure, she added. So, “the cost per plant is comprehensive in a way that one solar array or wind farm is not.”

Yet the Energy study found renewables would still be more competitive even with added system integration costs that would roughly double the levelized cost of electricity.

“These costs can stem from batteries, but there are also many other means of flexibility that can be used,” said Jens Weibezahn, one of the study’s corresponding authors and an economist at the Copenhagen Business School’s School of Energy Infrastructure.

Weibezahn’s group got similar results when they compared the projected market value for energy from small modular reactors with the weighted market value for renewable electricity at the time of generation. Costs for dealing with radioactive waste “will add a significant additional economic burden” on nuclear technologies, he added.

A March 2023 study by Colorado State University researchers suggested the economics for SMRs wouldn’t be dramatically better than those for large reactors. The researchers also found the levelized costs of electricity for different types of small modular reactors would be substantially higher than that for natural gas power plants without carbon capture.

However, “natural gas plants release tremendous amounts of greenhouse gases which engender societal and environmental costs,” said the paper in Applied Energy. Adding in carbon capture increased the estimated levelized cost of energy for the natural gas plants to the general range for the small modular reactors.

Commercial methane-fired power plants with carbon capture are not yet running at scale. The American Petroleum Association has objected to proposed rules that might effectively require such equipment.

How things will shake out in the future is unclear, said Jason Quinn, who heads the sustainability laboratory at Colorado State University and is the corresponding author for the March study. But, he added, “typically decisions are driven on economics, and current SMR estimates show them not to be a commercially viable solution as compared to other technologies.”

For now, initial production at the Centrus HALEU plant will meet a commitment to the Department of Energy. Centrus expects the plant will employ up to 500 direct employees when it moves to full-scale commercial production, said Larry Cutlip, vice president for field operations. Supporting industries will provide work for another 1,000 to 1,300 people. And all those workers could stimulate economic activity for roughly eight times as many jobs, he added.

Centrus already plans to supply HALEU fuel to TerraPower and Oklo, Inc. Each company has its own individual SMR design and is working with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission toward having the designs certified.

Oklo plans to build two sodium-cooled fast reactors in Piketon near the Centrus’s HALEU production plant. Each of the SMRs could supply up to 15 MW of electricity and more than 25 MW of clean heating, said spokesperson Bonita Chester.

Plans call for the SMRs to supply some carbon-free electricity for the Centrus facility. Other possible customers for electricity include commercial, industrial or municipal entities.

“As for the clean heating output, we envisage potential industrial partners and applications for district heating systems,” Chester said.

The ability to sell or otherwise use the heat as well as electricity could potentially lower the average costs.

“We are committed to ensuring that our electricity and heating output remain competitive with other forms of energy generation,” Chester added. “Our technology benefits from simplified design and cost-effective materials, making it an economically effective option.”

NuScale plans to deploy a dozen 77-megawatt small modular reactors in Ohio and another dozen in Pennsylvania for Standard Power data center projects by 2029. Those pressurized water reactors can use low-enriched uranium and won’t need HALEU, Hughes noted.

Deputy Secretary of Energy David Turk expects HALEU and small nuclear reactors that rely on it will be competitive.

“People appreciate the importance of baseload power, and I think that will be even more important as we further decarbonize the electricity economy,” Turk said. That will appropriately include more wind and solar energy, “but it’s good to have that baseload power to make it all work in the end.”

Electricity from SMRs will be “a real source of energy security and energy resilience,” Turk added. “You need diversification, but you need to have a variety of different inputs going into the system.”

“Nuclear certainly can provide baseload, but it does this at a cost significantly higher than an integrated renewables-based system,” Weibezahn said.

A bigger question may be whether there will be enough carbon-free electricity.

The Department of Energy estimates the United States will need to triple nuclear energy production to about 300 GW by 2050. That growth will be driven by advanced nuclear technologies, much of which will use HALEU.

“If we want to meet our climate goals and meaningfully reduce carbon emissions, we need all sources of clean energy, including wind, solar and nuclear energy,” said Jess Gehin, associate lab director for nuclear science and technology at Idaho National Laboratory. “Current projections show that we cannot meet our climate goals without nuclear energy.”