Hyundai Motor Group is building a facility at an existing steel plant in South Korea to test out its technology to produce direct reduced iron before opening its flagship project in Louisiana.

Last week, the automaker announced plans for a pilot-scale DRI plant at its Dangjin Steelworks in South Chungcheong province, southwest of Seoul. The facility already operates a coal-fired blast furnace, a basic oxygen furnace, and an electric arc furnace, which makes steel from recycled scrap metal.

But DRI, a cleaner method of making iron that relies on gas or hydrogen to turn ore into iron, instead of a more polluting blast furnace, was until now missing from the mix. Construction on the DRI facility has already begun. Once it’s complete, the facility will have the capacity to produce 30 kilograms of molten iron per hour and will provide key technical data to help inform the future U.S. operation; by contrast, a typical blast furnace can produce tens of thousands of kilograms of molten iron per hour.

Reports in the Korean newspaper Chosun Biz and the trade publications Hydrogen Central and Fuel Cell Works indicate that the DRI pilot will use hydrogen as the fuel for the iron-making process. While it’s not clear what kind of hydrogen Hyundai plans to use in South Korea, the company has said its debut steel plant in Louisiana will depend, at least for the first few years, on blue hydrogen, the version of the fuel made with gas equipped with carbon-capture equipment. In the mid-2030s, however, Hyundai intends to swap blue hydrogen for the green version, made with electrolyzers powered by carbon-free electricity.

Hyundai did not respond to emailed questions from Canary Media.

The Louisiana project, set to come online by 2029, will be the most significant clean steel facility in the United States. Hyundai has invested heavily in the U.S. as the South Korean automaker faces increased competition in Asia from Chinese car companies. In the U.S., automotive manufacturers are the largest consumers of primary steel. Since President Donald Trump returned to office last year, American steelmakers have largely doubled down on older, dirtier methods of making the metal.

That’s a problem for automakers that have pledged to curb emissions. Hyundai, for instance, has a goal of carbon neutrality by 2045. To ensure a supply of clean steel, Hyundai is charging ahead with its own plant, despite recent challenges from the Trump administration.

“We’re taking the positive view that they’re making this investment in South Korea,” said Matthew Groch, senior director of decarbonization at the environmental group Mighty Earth. “This is a good sign that they’re committed to clean operations in Louisiana.”

A debate playing out in Wisconsin underscores just how challenging it is for U.S. states to set policies governing data centers, even as tech giants speed ahead with plans to build the energy-gobbling computing facilities.

Wisconsin’s state legislators are eager to pass a law that prevents the data center boom from spiking households’ energy bills. The problem is, Democrats and Republicans have starkly different visions for what that measure should look like — especially when it comes to rules around hyperscalers’ renewable energy use.

Republican state legislators introduced a bill last week that orders utility regulators to ensure that regular customers do not pay any costs of constructing the electric infrastructure needed to serve data centers. It also requires data centers to recycle the water used to cool servers and to restore the site if construction isn’t completed.

Those are key protections sought by decision-makers across the political spectrum, as opposition to data centers in Wisconsin and beyond reaches a fever pitch.

But the bill will likely be doomed by a “poison pill,” as consumer advocates and manufacturing-industry sources describe it, that says all renewable energy used to power data centers must be built on-site.

Republican lawmakers argue this provision is necessary to prevent new solar farms and transmission lines from sprawling across the state.

“Sometimes these data centers attempt to say that they are environmentally friendly by saying we’re going to have all renewable electricity, but that requires lots of transmission from other places, either around the state or around the region,” said State Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, a Republican, at a press conference this week. “So this bill actually says that if you are going to do renewable energy, and we would encourage them to do that, it has to be done on-site.”

This effectively means that data centers would have to rely largely on fossil fuels, given the limited size of their sites and the relative paucity of renewable energy in the state thus far.

Gov. Tony Evers and his fellow Democrats in the state legislature are unlikely to agree to this scenario, Wisconsin consumer and clean-energy advocates say.

Democrats introduced their own data center bill late last year, some of which aligns closely with the Republican measure: The Democratic bill would similarly block utilities from shifting data center costs onto residents, by creating a separate billing class for very large energy customers. It would require that data centers pay an annual fee to fund public benefits such as energy upgrades for low-income households and to support the state’s green bank.

But that proposal may also prove impossible to pass, advocates say, because of its mandate that data centers get 70% of their energy from renewables in order to qualify for state tax breaks, and a requirement that workers constructing and overhauling data centers be paid a prevailing wage for the area. This labor provision is deeply polarizing in Wisconsin. Former Republican Gov. Scott Walker and lawmakers in his party famously repealed the state’s prevailing-wage law for public construction projects in 2017, and multiple Democratic efforts to reinstate it have failed.

The result of the political division around renewables and other issues is that Wisconsin may accomplish little around data center regulation in the near term.

“If we could combine the two and make it a better bill, that would be ideal,” said Beata Wierzba, government affairs director for the nonprofit clean-energy advocacy group Renew Wisconsin. “It’s hard to see where this will go ultimately. I don’t foresee the Democratic bill passing, and I also don’t know how the governor can sign the Republican bill.”

Wisconsin’s consumer and clean energy advocates are frustrated about the absence of promising legislation at a time when they say regulation of data centers is badly needed. The environmental advocacy group Clean Wisconsin has received thousands of signatures on a petition calling for a moratorium on data center approvals until a comprehensive state plan is in place.

At least five new major data centers are planned in the state, which is considered attractive for the industry because of its ample fresh water and open land, skilled workers, robust electric grid, and generous tax breaks. The Wisconsin Policy Forum estimated that data centers will drive the state’s peak electricity demand to 17.1 gigawatts by 2030, up from 14.6 gigawatts in 2024.

Absent special treatment for data centers, utilities will pass the costs on to customers for the new power needed to meet the rising demand.

Two Wisconsin utilities — We Energies and Alliant Energy — are proposing special tariffs that would determine the rates they charge data centers. Allowing utilities in the same state to have different policies for serving data centers could lead to these projects being located wherever utilities offer them the cheapest rates, and result in a patchwork of regulations and protections, consumer advocates argue. They say legislation should be passed soon, to standardize the process and enshrine protections statewide before utilities move forward on their own.

Some of Wisconsin’s neighbors have already taken that step, said Tom Content, executive director of Wisconsin’s Citizens Utility Board, a consumer advocacy group.

He pointed to Minnesota, where a law passed in June mandates that data centers and other customers be placed in separate categories for utility billing, eliminating the risk of data center costs being passed on to residents. The Minnesota law also protects customers from paying for “stranded costs” if a data center doesn’t end up needing the infrastructure that was built to serve it.

Ohio, by contrast, provides a cautionary tale, Content said. After state regulators enshrined provisions that protected customers of the utility AEP Ohio from data center costs, developers simply looked elsewhere in the state.

“Much of the data center demand in Ohio shifted to a different utility where no such protections were in place,” Content said. “We’re in a race to the bottom. Wisconsin needs a statewide framework to help guide data center development and ensure customers who aren’t tech companies don’t pick up the tab for these massive projects.”

Limiting clean energy construction to data center sites could be especially problematic, as data center developers often demand renewable energy to meet their own sustainability goals.

For example, the Lighthouse data center — being developed by OpenAI, Oracle, and Vantage near Milwaukee — will subsidize 179 megawatts of new wind generation, 1,266 megawatts of new solar generation, and 505 megawatts of new battery storage capacity, according to testimony from one of the developers in the We Energies tariff proceeding.

But Lighthouse covers 672 acres. It takes about 5 to 7 acres of land to generate 1 megawatt of solar energy, meaning the whole campus would have room for only about a tenth of the solar the developers promise.

We Energies is already developing the renewable generation intended to serve that data center, a utility spokesperson said, but the numbers show how future clean energy could be stymied by the on-site requirement.

“It’s unclear why lawmakers would want to discriminate against the two cheapest ways to produce energy in our state at a time when energy bills are already on the rise,” said Chelsea Chandler, the climate, energy, and air program director at Clean Wisconsin.

Renew Wisconsin’s Wierzba said the Democrats’ 70% renewable energy mandate for receiving tax breaks could likewise be problematic for tech firms.

“We want data centers to use renewable energy, and companies I’m aware of prefer that,” she said. “The way the Republican bill addresses that is negative and would deter that possibility. But the Democratic bill almost goes too far — 70%. That’s a prescribed amount, too much of a hook and not enough carrot.”

Alex Beld, Renew Wisconsin’s communications director, said the Republican bill might have a hope of passing if the poison pill about on-site renewable energy were removed.

“I don’t know if there’s a will on the Republican side to remove that piece,” he said. “One thing is obvious: No matter what side of the political aisle you’re on, there are concerns about the rapid development of these data centers. Some kind of legislation should be put forward that will pass.”

Bryan Rogers, environmental director of the Milwaukee community organization Walnut Way Conservation Corp, said elected officials shouldn’t be afraid to demand more of data centers, including more public benefit payments.

“We know what the data centers want and how fast they want it,” he said. “We can extract more concessions from data centers. They should be paying not just their full way — bringing their own energy, covering transmission, generation. We also know there are going to be social impacts, public health, environmental impacts. Someone has to be responsible for that.”

Utility representatives expressed less urgency around legislation.

William Skewes, executive director of the Wisconsin Utilities Association, said the trade group “appreciates and agrees with the desire by policymakers and customers to make sure they’re not paying for costs that they did not cause.”

But, he said, the state’s utility regulators already do “a very thorough job reviewing cases and making sure that doesn’t happen. Wisconsin utilities are aligned in the view that data centers must pay their full share of costs.”

If Wisconsin legislators do manage to pass data center legislation this session, it will head to the desk of Evers. The governor is a longtime advocate for renewables, creating the state’s first clean energy plan in 2022, and he has expressed support for attracting more data centers to Wisconsin.

“I personally believe that we need to make sure that we’re creating jobs for the future in the state of Wisconsin,” Evers said at a Monday press conference, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “But we have to balance that with my belief that we have to keep climate change in check. I think that can happen.”

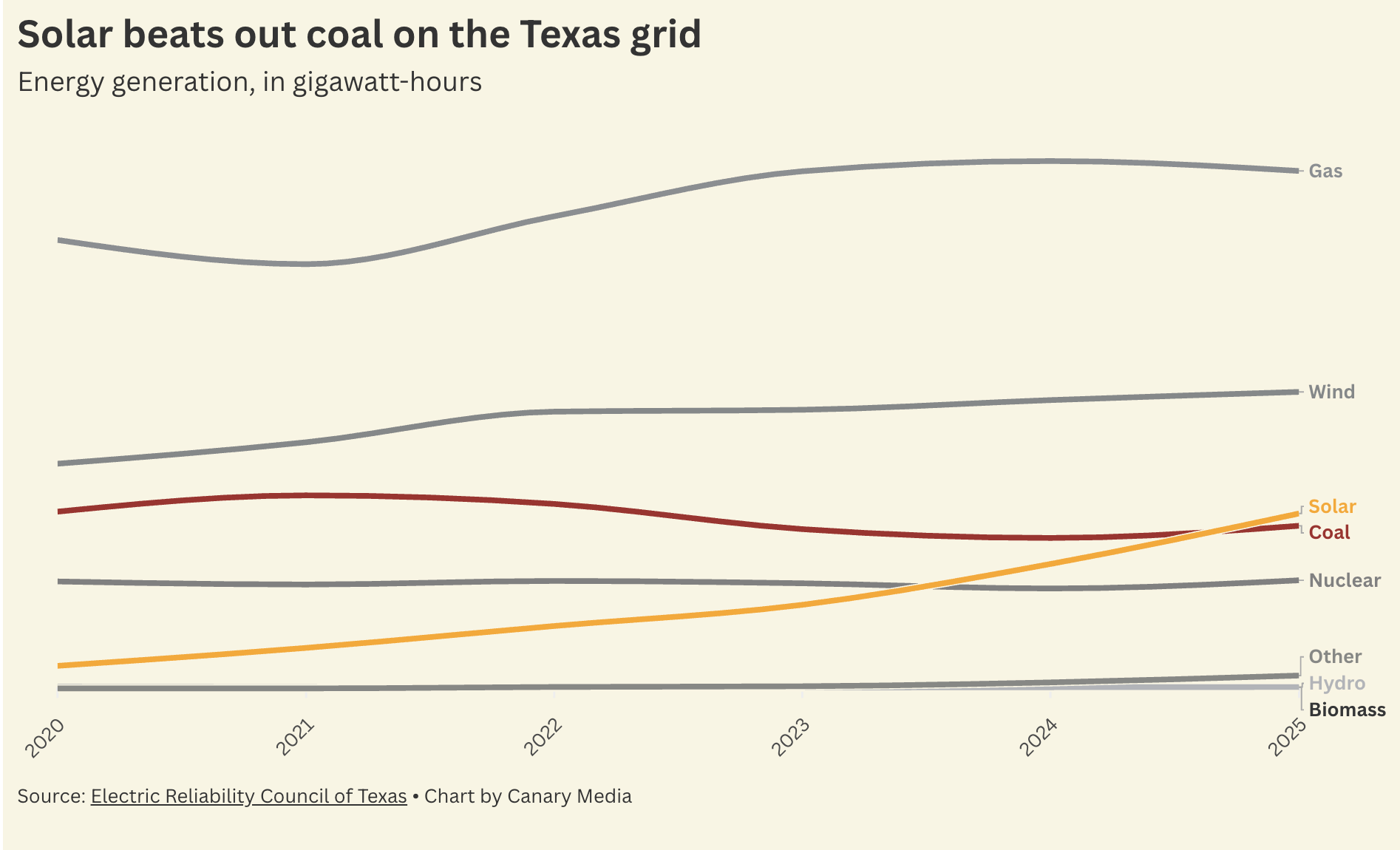

Texas just hit a huge milestone: It got more electricity from solar than it did from coal last year, a first for the second-biggest state in the country.

That’s a big shift from a few years prior. Back in 2020, the Texas grid got just 2% of its electricity from solar power and 18% from coal, according to the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, which operates the grid for the vast majority of the state. In 2025, nearly 14% of ERCOT’s electricity came from solar — and just under 13% was produced by burning coal.

Texas, long a leader on wind energy, has been building solar at a blistering pace in recent years. It’s now the state with the most utility-scale solar capacity, beating out longtime champion California for the top spot.

It makes sense that solar has taken off in Texas. Two things it has in spades are sunshine and land, and ERCOT’s competitive markets and fast interconnection processes are appealing to solar developers. In recent years, the state’s solar boom helped create one of the nation’s hottest markets for grid batteries, which in turn has strengthened the business case for installing even more solar.

Meanwhile, coal has been declining in Texas for more than a decade, knocked off balance first by a combination of fracked gas and cheap wind power.

Overall, however, fossil fuels still produce the majority of Texas’s electricity. The state got 54% of its power last year from coal and gas, with the latter fuel serving as Texas’ biggest source of electricity by a long shot.

It’s worth noting that solar beat out coal in what was a comeback year for the fossil fuel, in Texas and beyond. After two years of declines, coal generation jumped by 8% in Texas in 2025. But because solar grew so fast — by a staggering 41% last year — the clean-energy source eclipsed coal anyway.

Not everyone in Texas is happy about the rising tide of solar.

Some state Republicans have tried and failed, several times now, to limit the growth of clean energy. Instead, they’d like to see the construction of natural gas plants to meet the state’s surging electricity demand. But Texas faces the same reality as the rest of the country: Solar and storage are simply too cheap and easy to deny.

As the Trump administration wages a high-profile attack on the nation’s offshore wind farms, it has also been quietly fighting a brutal battle with renewable energy projects on land.

Since President Donald Trump took office nearly a year ago, his administration has announced at least two dozen policy and regulatory actions aimed at hindering the build-out of wind and solar projects, including rescinding federal tax credits, withdrawing grants and loans, and freezing permitting approvals. Yet one measure in particular has had an outsize chilling effect — and is facing a new legal challenge from clean energy groups.

Last summer, the U.S. Interior Department announced that all decisions related to wind and solar projects would require an “elevated review” by Secretary Doug Burgum, saying this would end the Biden administration’s “preferential treatment” for renewables. In a July memo, the agency listed nearly 70 types of permits and other actions that now need Burgum’s personal sign-off, adding cost and time and creating significant anxiety for developers, experts say.

Over 22 gigawatts of utility-scale wind and solar projects on public lands have been canceled or are held up as a result of the order, according to Wood Mackenzie data and the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management website. That’s enough capacity to power roughly 16.5 million U.S. homes — a significant amount at any point, but especially when the country is clamoring for more low-cost electricity as energy demand and utility bills soar.

“We’re seeing electricity costs go up all around the country, and the cheapest electrons that we can put into the supply side of that equation are all stuck on Secretary Burgum’s desk,” Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.) told Canary Media.

Solar represents the bulk of that figure, with 18 GW of facilities scrapped or considered inactive as of December, by Wood Mackenzie’s count. Nearly 90% of those projects also included energy storage, given that many were slated for desert regions in the Southwest, said Kaitlin Fung, a research analyst for the consultancy.

“It’s created a choke point,” Fung said of Interior’s memo. She noted that the Bureau of Land Management has advanced permits for only one renewable energy project since July: the 700-megawatt Libra Solar facility in Nevada. Meanwhile, federal oil and gas permits have surged in the first year of Trump’s term.

Many other projects remain stuck in permitting limbo as developers await the approvals they need — from quick consultations to complex reviews — in order to secure financing and begin building their large-scale renewable energy installations. That’s true for wind and solar farms on private and state lands as well, since those projects might require federal approval for things like wildlife and waterway impacts.

The holdups are occurring as the United States teeters on the edge of an electricity crisis. Demand is climbing across the nation, causing household utility bills to soar, and more power plants are needed to satisfy the surge in AI data centers, factories, and electrified cars and buildings. Large-scale solar and onshore wind projects are among the fastest and lowest-cost ways to add power to the grid — faster than Trump’s preferred path of building new gas-fired power plants or restarting shuttered nuclear reactors.

Heinrich, the ranking member of the U.S. Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, cited the gigawatts of stalled projects in a Senate floor speech earlier this month. He and other Democratic leaders have said that any efforts to pass bipartisan legislation on energy permitting reform are “dead in the water” so long as the Trump administration continues to block development of onshore wind and solar and cancel fully permitted offshore wind farms.

“The concern is that we put a balanced legislative package together that gives certainty to both traditional [oil and gas] energy and renewables — but if this administration is going to say yes to all of the fossil projects and create a de facto moratorium on all of the renewable and storage projects, then we haven’t accomplished anything,” Heinrich said by phone.

In recent weeks, a coalition of clean energy organizations sued to overturn the July memo and other actions from Interior and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which issues permits for energy projects near navigable waters. Both the Army Corps and Interior say they’re prioritizing projects that generate the most energy per acre, a measure that favors coal, oil, and gas and undercuts renewables — and which has its roots in fossil-fuel industry misinformation.

Such actions “arbitrarily and discriminatorily place wind and solar technologies into a second-class status compared to other energy sources,” the groups said in a statement this week. “The Trump administration has choked private developers’ ability to build new and urgently needed energy projects across the nation.”

For solar and storage in particular, nearly 520 proposed projects totaling 117 GW of capacity have yet to receive all the necessary federal, state, and local permits, which puts them at risk of being delayed by the Trump administration, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association. The projects represent half of the country’s new planned power capacity.

Many developers are simply receiving radio silence from agencies whose approval or advice they need, said Ben Norris, SEIA’s vice president of regulatory affairs, who likened the agencies’ actions to a “blockade on solar permits.” Fung noted one mundane but significant effect of Interior’s memo: Wind and solar developers are now excluded from using an online government planning tool that helps streamline environmental reviews, a move that creates additional costs and complexity for companies.

The delays come as developers are racing to qualify for federal tax credits under the newly shortened timelines. Wind and solar installations must either start construction this summer or be operating by the end of 2027 to access incentives. “Time is really of the essence for many of these projects,” Norris said. In the absence of Congress passing a permitting-reform bill, he added, the Trump administration could simply remove many of the roadblocks it created by revoking its memos and other actions.

“If they were really serious about affordability and addressing power bills, they could take these steps today,” he said.

This analysis and news roundup come from the Canary Media Weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it every Friday.

The Trump administration had a tough week in court, starting with a Monday ruling that could pave the way for states and cities to unlock billions of dollars in revoked clean-energy grants.

Back in October, the Trump administration terminated a massive $7.6 billion in federal funding for climate and clean energy projects. There was a clear pattern to the clawback: Nearly every grant would’ve benefitted a state that voted for Democratic nominee Kamala Harris in the 2024 presidential election.

And the White House wasn’t exactly hiding its politically driven motivations. In a post on X announcing the rollback, Russ Vought, director of the Office of Management and Budget, referred to the revoked grants as “Green New Scam funding to fuel the Left’s climate agenda.”

St. Paul, Minnesota, was among the cities, states, and organizations that lost funding — $560,844 for expanding EV charging, to be exact. So the city partnered with a handful of environmental groups to fight back in a lawsuit that resulted in a big admission from the Trump administration. In a December filing, Justice Department lawyers said they would not contest the assertion that a state’s votes for Democrats influenced the termination decisions.

U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta called out that assertion in his ruling, writing that “defendants freely admit that they made grant-termination decisions primarily — if not exclusively — based on whether the awardee resided in a state whose citizens voted for President Trump in 2024.”

While Mehta ordered the Trump administration to release about $28 million to St. Paul and its fellow plaintiffs, billions of dollars’ worth of other grants remain frozen. But one former U.S. Energy Department official told Latitude Media the win lays a clear path for other awardees to sue: “If the administration doesn’t reverse all of the terminations, then they should prepare for hundreds of additional similar lawsuits.”

Three big wins for offshore wind

Offshore wind is beginning to move and groove again after the Trump administration’s December order that the nation’s five in-progress wind farms halt construction.

On Monday, a federal judge allowed Revolution Wind to resume work off the coast of Rhode Island. Equinor won a similar ruling on Thursday to keep building its Empire Wind project near New York. And Friday brought a third victory, with a judge letting Dominion Energy’s Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind forge ahead. There’s no word yet on whether the two other affected installations can restart construction.

The federal stop-work order has put billions of dollars, thousands of jobs, and gigawatts of much-needed power in jeopardy. Grid operator PJM Interconnection intervened in the Virginia project’s lawsuit late last week, saying its delay would threaten power supplies in the region. Equinor had said it may need to cancel Empire Wind altogether if it couldn’t restart work this week.

Meanwhile, Revolution Wind developer Ørsted said it’s not taking the court win for granted, and will hurry to install its final seven turbines before more setbacks arise.

A disappointing rebound in carbon emissions

After two years of declines, U.S. carbon emissions rose in 2025, according to a new Rhodium Group report. The 2.4% year-over-year increase is the third largest the U.S. has seen in the past decade, and shows that while the country is still heading toward decarbonization, major hurdles stand in its way.

Part of the increase can be chalked up to statistical “noise,” including an extra-cold winter that increased buildings’ space-heating needs, Rhodium Group analyst Michael Gaffney told Canary Media’s Julian Spector. But electricity usage also surged, largely thanks to data centers and other large power consumers, and carbon-spewing coal plants ramped up to meet that demand.

“This year is a bit of a warning sign on the power sector,” Gaffney said.“With growing demand, if we continue meeting it with the dirtiest of the fossil generators that currently exist, that’s going to increase emissions.”

Coal plans confirmed: U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright says the Trump administration intends to keep many more coal plants open past their scheduled closing dates, which could saddle utility customers with excessive costs. (New York Times)

Dismissing public health: The U.S. EPA plans to stop calculating how much money the country saves in avoided health care costs and deaths when it curbs fine particulate matter and ozone pollutants. (CNBC)

Make way for clean energy: California’s Westlands Water District approves a plan to build up to 21 GW of solar generation and another 21 GW of battery storage on water-parched land, which would be the largest solar and battery project in the country. (Canary Media)

You can pay your own way: New York Gov. Kathy Hochul (D) announces a plan to make sure data center power demand doesn’t raise costs for residents — a concept President Donald Trump also voiced support for in a social media post this week. (Axios, Washington Post)

Steel status report: 2025 saw major U.S. steel companies backing away from decarbonization investments and recommitting to coal-fired blast furnaces, but global demand for green steel is still on track to grow in the new year. (Canary Media)

The state of solar: Illinois’ solar industry is thriving despite federal obstacles, creating jobs that workforce training programs are preparing young people to fill. (Canary Media)

The Trump administration wants PJM Interconnection, the country’s biggest power market, to force data center developers to pay directly for the new power plants they need. It’s the latest attempt to curb skyrocketing energy costs for the roughly 67 million people PJM serves from Virginia to Illinois.

On Friday, the National Energy Dominance Council and governors of some PJM states released an agreement that urges the grid operator to take action to solve its massive affordability and grid-reliability problems.

Specifically, it presses PJM to speed up the construction of more than $15 billion worth of “reliable baseload” power plants by providing them with 15 years of revenue certainty. It also directs PJM to “require data centers to pay for the new generation built on their behalf — whether they show up and use the power or not.”

But industry experts warned that these demands would be difficult, if not impossible, to execute fast enough to make a difference for the region.

“It’s not at all clear how this can actually get implemented,” Rob Gramlich, president of consultancy Grid Strategies, told Canary Media. “How would this ever get implemented — and would this require changes that usually take five years?”

The vision, according to an anonymous White House official quoted by Bloomberg, is to require PJM to set up an emergency auction by September, which would compel data centers and other “large loads” to pony up the $15 billion to spur new power plant construction.

PJM is already under a December order from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to overhaul its rules for how massive data centers can interconnect to its grid.

The grid operator has also been slowly working on reform of its own. Its monthslong effort to get stakeholders — including utilities, power plant owners, big corporate energy users, data center developers, and consumer advocates — to agree on new structures to deal with the rising cost impacts of data centers ended in deadlock late last year. In a twist of fate, PJM released its decision on this matter later on Friday.

That plan has not yet been reconciled against the Trump administration’s just-released principles — PJM itself was not invited to the Friday White House event at which the agreement was announced, spokesperson Jeffrey Shields told Bloomberg.

Now, “PJM is reviewing the principles set forth by the White House and governors,” Shields said in a statement to Canary Media. “We will work with our stakeholders to assess how the White House directive aligns with the [large-load plan].”

The agreement’s goal is ultimately to curb PJM’s skyrocketing capacity costs, which are driven by the grid operator’s inability to build new generation or energy storage capacity fast enough to meet booming demand.

PJM’s rising utility rates are driving backlash from consumers — and demands from politicians to take action, including limiting data center growth.

“The principle of new large loads paying their fair share is gaining consensus across states, industry groups, and political parties,” Gramlich said. “The rules that have been in place for years did not ensure that.”

But Gramlich highlighted that Friday’s plan will run into the same state-vs.-federal jurisdictional conflicts that have stymied PJM’s efforts to reform data-center interconnection to date.

First off, PJM’s capacity auctions operate by allowing power plants, battery projects, demand-response providers, and other “supply-side” providers to bid their capacity into the system. Those capacity costs are then passed along to utilities, he noted. Utility customers themselves — including data centers — are not part of that equation.

“Even if the large loads voluntarily participate, there’s no mechanism currently for direct participation of a retail customer in a wholesale auction,” Gramlich said.

What’s more, data centers remain customers of utilities regulated at the state level. “It might require changes in state law in any PJM state” to alter those facts, he said.

Even if such state policies were put in place, there’s no guarantee that the prospective data centers would play ball, he said. “It’s easy to hold an auction, but the hard part is compelling anyone to participate.”

The new agreement faces other fundamental challenges, too.

While the text doesn’t specify the exact type of power plants it wants PJM to build, its call for “reliable baseload power generation” is code for fossil fuels or nuclear power. That will pose problems. Demand for gas turbines has pushed delivery orders for new power plants out to 2028 or later. Almost all of the new gas-fired power plants secured in PJM’s fast-track procurement last year aren’t set to come online until 2030 or later. And nuclear power plants usually take about a decade to build.

Meanwhile, more than 100 gigawatts of potential new grid resources, the vast majority of which are solar, wind, and batteries, remain stuck in PJM’s badly congested interconnection queue. PJM is still working on efforts to fast-track these resources by, for example, pairing batteries with existing solar and wind farms.

Ultimately, an auction of the kind the White House plan envisions could drive investment in more power plants, according to Julia Hoos, head of USA East at Aurora Energy Research — but it could also “exacerbate some other elements of PJM’s challenges.”

“Everyone agrees that PJM is struggling to bring online new generation fast enough, and that some sort of intervention is required,” Hoos wrote in a Friday email. But she added that “PJM already has several ongoing reform processes to address these issues — and it’s pretty unprecedented for this sort of top-down intervention to direct PJM’s efforts.”

North Carolina’s predominant utility is backing away from a long-held plan to double the size of its largest pumped storage hydropower plant — just as data centers and other voracious energy users threaten to stretch power supplies to their limit.

The reversal was tucked away in Duke Energy’s latest long-term blueprint, which was filed in October and will be evaluated and finalized by regulators this year. Clean energy advocates had expected to fight that blueprint on familiar fronts — from its inclusion of new gas-fired power plants to its complete lack of near-term wind energy — but they were surprised by the backpedaling on the Bad Creek storage facility, located just over the border in South Carolina.

“Duke put this forward as something they were going to do, and everybody agreed,” said David Neal, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center. “To take out the one thing that everybody agreed on, without any announcement, without any fanfare,” he said, “is just baffling to me.”

Pumped hydro is a uniquely useful form of carbon-free electricity. It’s available on demand and can dispatch power over a much longer period than a lithium-ion battery can. It’s also rare: Construction of new pumped hydro facilities in the U.S. has stagnated for decades.

Duke’s original Bad Creek expansion plan would have catapulted the company to become the nation’s leader in pumped hydro. Now, advocates fear its about-face will undermine the state’s zero-carbon law by opening the door for a fleet of new gas plants instead.

Hydropower is one of the oldest forms of electricity generation — and it’s how Duke Energy, then called the Catawba Power Company, got its start in the early 1900s. A trio of entrepreneurs, led by James B. Duke, built a series of dams and lakes along the Catawba River, fostering the growth of mills and other industries that helped diversify the region’s economy.

Today, traditional hydropower makes up a tiny fraction of Duke-owned power capacity, with nearly 1.3 gigawatts spread across 25 different sites in the Carolinas. There’s no push to change that number, as conservation groups focus on removing the thousands of other dams in North Carolina that provide little to no upside to outweigh the ecological damage they cause.

Pumped storage hydropower — like that at Bad Creek — is a related but different beast. Two bodies of water at different elevations are connected with reversible turbines, producing or storing electricity, depending on what the grid needs.

“Let’s say it’s a spring day, a sunny day, a lot of solar on the grid, but not a lot of demand. You just bring that water uphill,” to store in the upper reservoir, Neal explained. “When you’re in a peak period, you run the water back downhill to generate electricity. It’s a very efficient, clean way of having storage.”

Duke launched its first pumped storage project in 1975 after building a dam between what is now Lake Jocassee and Lake Keowee below it. On the South Carolina side of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the four reversible turbines are slated to operate for at least another two decades.

The Bad Creek complex followed in 1991. The upper reservoir sits at an elevation of 2,310 feet, and Lake Jocassee, more than 1,000 feet below, serves as the lower reservoir. They’re linked by an underground concrete tunnel and a four-turbine powerhouse, capable of supplying enough electricity to power 1 million homes.

Totaling over 2.4 gigawatts, the Jocassee and Bad Creek plants function as massive batteries, and are the largest source of energy storage anywhere on Duke’s six-state electric system. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, only two states, Virginia and California, have more pumped storage capacity.

Duke recently upgraded the existing Bad Creek facility, increasing its capacity to nearly 1.7 gigawatts. But the utility has also long envisioned drilling a new tunnel and adding another four-turbine powerhouse at the site, adding another roughly 1.8 gigawatts. Doing so would help the company zero out its carbon emissions by midcentury, as required by state law.

In 2022, the company offered four pathways to limit its pollution; all included the expansion, dubbed Bad Creek II, by 2034. The additional Bad Creek capacity was also cemented in a compromise Duke struck with stakeholders to help get its last carbon-reduction plan approved. Regulators on the North Carolina Utilities Commission blessed the deal, directing the company to pursue “all reasonable development activities” to put Bad Creek II in place.

But in October, when Duke submitted its 2026 carbon proposal, Bad Creek II was barely mentioned. Among 10 different pathways the company charted toward climate neutrality, only one included the new pumped storage capacity.

Earlier in 2025, Duke had quietly removed Bad Creek II from an engineering study that evaluated the impact of new power plants on the transmission system. The removal means that the soonest Bad Creek II could come online is now 2040 — six years later than previously envisioned — but the company doesn’t recommend even that late date or pinpoint a new one.

“Notwithstanding the delayed development timeline,” Duke said in its plan, the utility remains “committed to exploring the potential for additional [pumped storage hydro] capacity at the Bad Creek II site.”

The backtracking has alarmed clean energy advocates, who point out how well pumped storage complements other sources of renewable energy. Duke’s own modeling shows that adding Bad Creek II would enable more solar, onshore wind, and batteries, while eliminating the need for over 2 gigawatts of new gas plants.

“That all seems like a really good deal, and if we could do that sooner, as Duke had committed to in the last plan, and as the commission ordered it to do,” Neal said, “we’d be on such a clear path to complying with state law and having a much more diverse portfolio.”

Duke acknowledged that Bad Creek II would lead to lower overall costs than its preferred plan through 2050. Viewed in that light, Neal said, “it seems like a really bad deal for customers for Duke to be turning its back on this project.”

In its proposal, Duke offered no specifics on the long-term cost impacts of Bad Creek II, but did say that removing it from the grid impact study showed savings of approximately $358 million in “network upgrade costs.” By punting on the project, the company also put off spending tens of millions of dollars on development activities.

Asked for more justification, beyond those up-front savings, for Duke’s bid to delay the project, spokesperson Bill Norton said via email: “More work is needed to assess whether Bad Creek II will be part of a least-cost plan for customers.”

As to whether the company might shelve the project entirely, Norton said that it “remains a potential resource in the future.” He added that Duke plans to spend enough money to qualify the expansion for time-limited 30% federal tax credits and that the potential for additional turbines is included in Duke’s relicensing application to federal regulators.

“While there is no specific timeline today for a second powerhouse,” Norton said, “our continued licensing work preserves the option for the future, and we will continue to engage our regulators on this decision.”

As the commission evaluates Duke’s long-term plans, advocates will be pushing for a green light on the Bad Creek expansion — especially as an alternative to the other, more speculative sources of firm power that the utility is banking on, like small modular reactors.

In contrast to that form of nuclear power, pumped hydro is “not a nascent technology,” said Justin Somelofske, senior regulatory counsel at the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association. That’s why in past hearings over the utility’s plans, he noted, “it was the one resource that was not in controversy and not contested.”

“One of the biggest things that we consistently hear from the Utilities Commission is the need for more dispatchable, reliable generation,” Somelofske said. “Pumped storage satisfies that need.”

In some parts of California, the lead state on electric vehicles, utilities are facing a challenge that will eventually spread nationwide: Local grids are struggling to keep up with the electricity demand as more and more drivers switch to EVs.

The go-to solution for this type of problem among most utilities is to undertake expensive upgrades, paid for by all their customers, so that the grid can accommodate the new load.

But there’s a cheaper option: Utilities could simply make sure that the EVs that plug into their grids aren’t all charging at the same time.

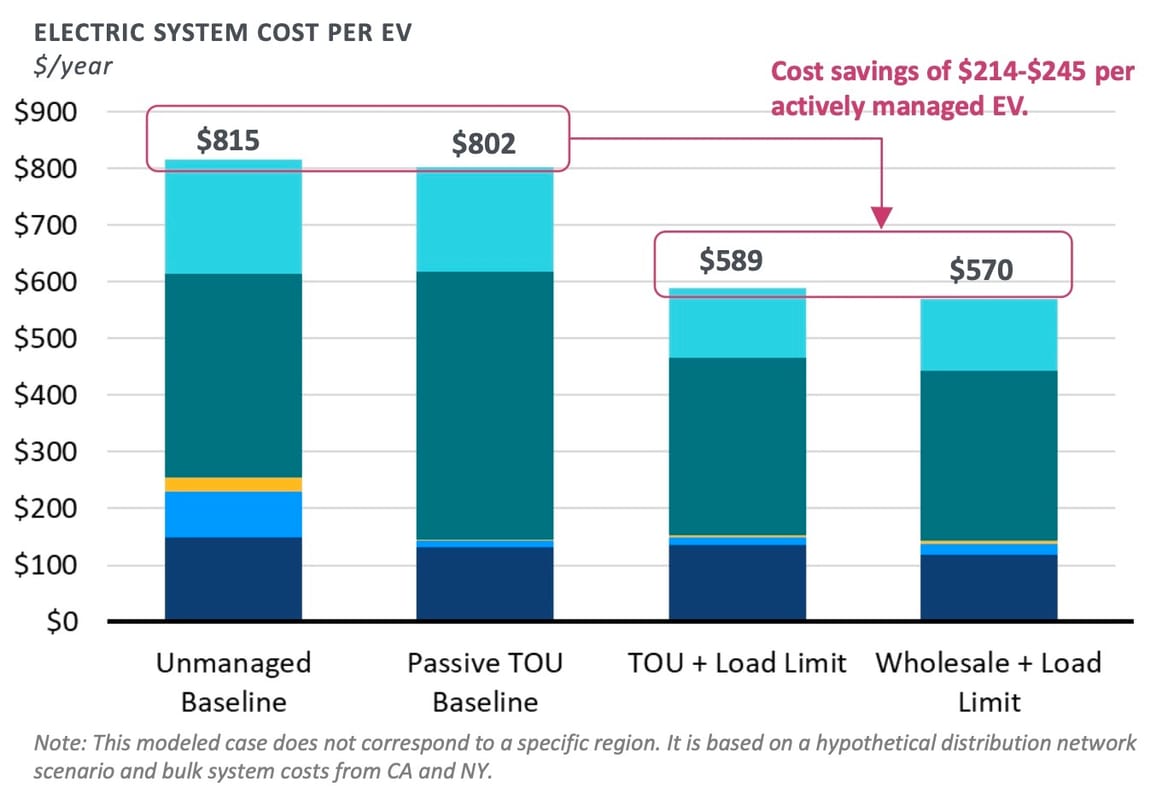

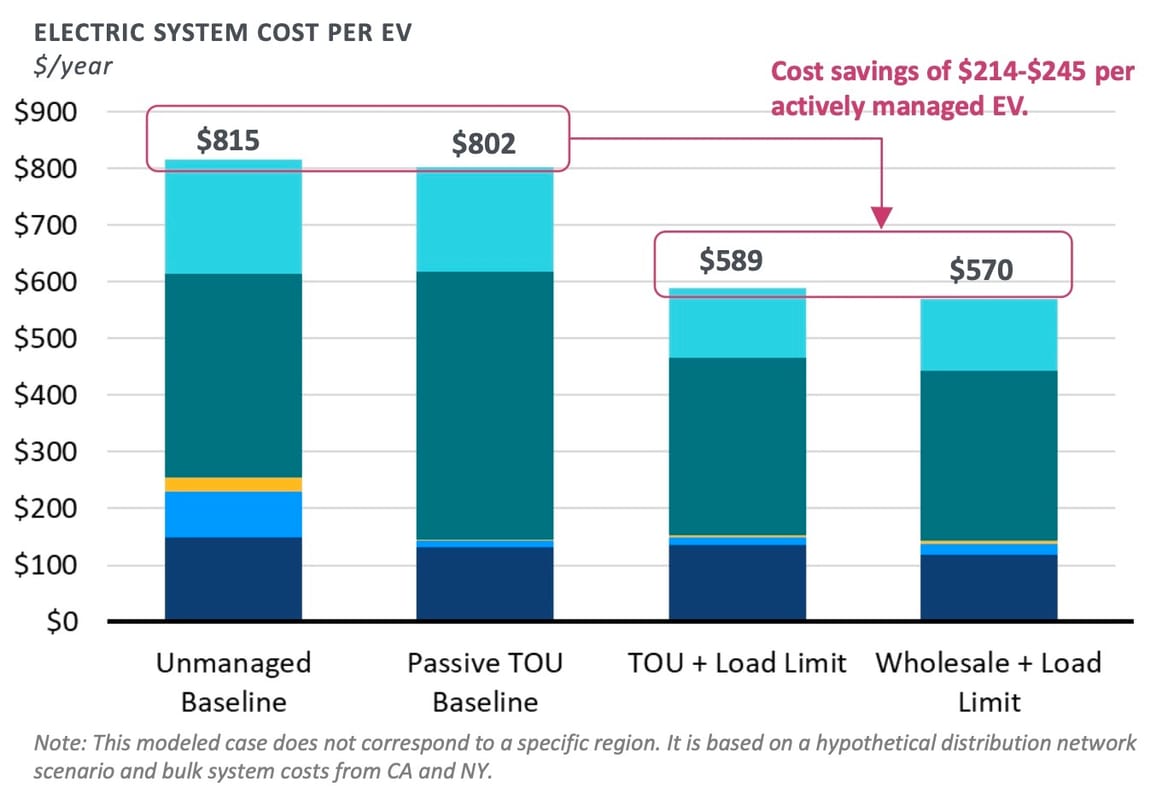

So finds a new report prepared by The Brattle Group, an energy consultancy, on behalf of EnergyHub, a company that operates virtual power plants (VPPs) for more than 170 utilities. In an analysis of 58 EV owners in Washington state, the authors found big cost benefits from “active managed charging,” the process of modulating when and how much EVs charge to minimize their impact on the grid.

It’s a crucial finding, as researchers say the approach is most effective when deployed before lots of EVs show up on utilities’ grids. Previous research has found that the cost of unmanaged charging could add as much as $2,500 per utility customer once EVs reach higher levels of penetration on utility grids. In California, that cost is already impacting utilities’ plans. Other fast-growing EV regions, including New York and Massachusetts, could soon face similar challenges.

Managed charging is a simple concept but not a simple task. To make it work, utilities have to get EV owners to enroll in managed charging programs, which requires convincing them that they won’t be left with a depleted battery when they need to drive somewhere.

Utilities also need to persuade their regulators — and their own internal grid planners — that these charging regimes are reliably relieving the local transformers, feeder lines, and substations that would otherwise be overloaded by too many EVs charging at once. If utilities can’t do that, they’ll wind up having to build new grid infrastructure anyway.

Managed charging isn’t a new idea. Utilities across the country are starting to test such programs operated by EnergyHub, Camus Energy, ev.energy, Kaluza, WeaveGrid, and other companies.

And the benefits of scaling up such programs could be major, said Akhilesh Ramakrishnan, managing energy associate at The Brattle Group. “With active managed charging, you can roughly double the capacity of the grid to host EVs,” he said.

That would help utilities contain the high and rising costs of maintaining and expanding their distribution grids, which now make up the biggest share of rapidly rising U.S. utility rates.

To achieve the savings that this approach promises, “it’s really important that the solution is implemented without damaging customers’ reliance on their cars,” Ramakrishnan said — in other words, making sure “that their cars are charged by when they need them.”

That’s where more sophisticated managed charging comes in, said Freddie Hall, a data scientist at EnergyHub. The company runs managed EV charging pilots for utilities such as Arizona Public Service and Southern Maryland Electric Cooperative, and applied similar techniques to the EV drivers in Washington state analyzed for the new report.

EnergyHub takes pains to forestall the risk of leaving EV owners without the charge they need by the time they need it, Hall said. For example, “we’ve found that some people don’t constantly update their charge-by time settings,” he said, referring to the deadline that each driver sets to have a full battery. So EnergyHub uses drivers’ past charging behaviors to forecast when they typically unplug and to make sure they’re scheduled to be fully charged by that time.

Occasionally, that requires allowing EVs to collectively pull more power from the grid than permitted under the “load limits” that utilities have set for the transformers, distribution feeders, and substations delivering it, he noted. To deal with that, EnergyHub dispatches charging in ways that minimize those overloads: “We spread out that charging to achieve a lower peak over a longer duration.”

EnergyHub’s managed charging doesn’t just limit impacts on the distribution grid, Hall said, but also co-optimizes for when power is cheaper across the grid at large. It targets times when wholesale electricity prices are low — although it will choose to forego that cheaper energy if using it would violate its local load-limit settings.

These techniques require a lot of information, making them harder to implement than time-of-use rates — the most common way that utilities try to limit EV charging loads today.

Those programs typically charge more for power at times when the grid at large is under peak demand stress, usually during late afternoons or early evenings in the summer or early mornings in the winter, and they charge less for power during off-peak times, typically late at night.

But these time-of-use rates can actually cause more grid stress than they resolve, Ramakrishnan said. That’s because they create a secondary “snapback effect” when rates change from expensive to cheap, and everyone’s EV starts charging at once.

“We’re not trying to say that time-of-use is a bad solution in general, or doesn’t work at all,” Ramakrishnan said. “At lower penetrations, there’s value in shifting EV load to move away from the time that other loads peak. But fairly quickly — when you get to 7% to 10% penetration — EVs themselves start to set the peak.”

That’s one reason why the report recommends that utilities start working on active managed charging programs before EV purchases start to overwhelm the grid. The other reason is to match the pace of how utilities plan ahead for grid investments, Hall said.

“I worked at two utilities before coming to EnergyHub. Grid planning is a multiyear-type deal,” he said. “Getting infrastructure for the distribution grid takes up to 18 or more months. Solutions like these help utilities put off some decisions for up to 10 years, if not more.”

The ability to push out grid upgrades is particularly valuable at a time when power demands are growing even as utilities are under pressure to contain costs, Ramakrishnan said. “A lot of utilities are capital constrained right now.”

At the same time, EVs represent a massive opportunity for utilities to increase electricity sales — and that could put downward pressure on the rates that all customers have to pay. That’s because regulators set those rates based on how much money utilities need to earn to cover their costs. More sales divided by fewer costs means lower rates over the long run.

At the very least, managed charging can better align EVs’ costs with their benefits, Ramakrishnan said. “One, you push the upgrade out and can save money for longer,” he said. “Two, the upgrade gets pushed out to when there are more EVs — that means there are more EVs paying for it.”

The mid-Atlantic grid operator PJM Interconnection faces a capacity crunch of titanic proportions as AI computing investment rushes headlong into its 13-state region, home to more than 67 million people. The most recent PJM capacity auctions — where the grid operator pays in advance for power plants to be available to serve the grid — hit record-high clearing prices in December, portending more expensive electricity for the region.

The developer Elevate Renewables is tackling that dire need by accomplishing something unheard of in the PJM region: building a really big battery. The company, launched by private equity firm ArcLight in 2022, announced today that it had acquired a 150-megawatt/600-megawatt-hour battery project in northern Virginia and will complete construction by mid-2026. Called Prospect Power, the project could be bolstering the grid near the state’s famed “Data Center Alley” just in time for the summer spike in electricity use.

“The states want capacity, they want affordability, they want in-state resources,” Elevate CEO Joshua Rogol told Canary Media. “Storage can clearly be part of the solution to that problem. It is one of the few resources that can come online quickly, given how long it takes to develop and build a project given the supply chain as it exists today.”

Fossil gas still generates more power across the U.S. than any other resource, but battery storage has become the top source of on-demand power being built today (solar, as an intermittent producer, does not meet that definition).

However, almost all the storage action, and its resulting benefits, has happened in California and Texas. Data firm Modo Energy drew the comparison in a report last year: “In the past five years, PJM has added just 200 MW of grid-scale battery capacity — while Texas and California have cumulatively built more than 20 GW of [battery energy storage systems] over the same period.” It’s as if a major swath of the country saw a few states adopting smartphones and said, “No, thanks, we’re happy with flip phones.”

PJM’s failure to keep up with this particular grid technology is particularly surprising because PJM actually created the modern storage market back in 2012, by letting batteries compete for the rapid-fire grid service known as frequency regulation. Those rules spurred a buildout of 181 megawatts by 2016, according to Modo — heady stuff at the time, and well before storage in California and Texas took off. But these batteries tended to have just 15 minutes of duration, because that’s all that was needed to perform that role for the grid.

“The economic strategy was always to build a very short-duration battery, just participate in regulation services and make really substantial returns that way,” said Julia Hoos, head of USA East at Aurora Energy Research.

Frequency regulation has stayed lucrative for battery owners, Hoos noted, in part due to quirks in PJM’s rules that reserved some of the market for thermal generators like gas plants, which set a higher clearing price than batteries do. But rule changes now underway will likely reduce the payoff in future years.

In any case, the amount of regulation PJM needs for the grid isn’t enough to support a larger battery buildout on its own. Currently, PJM has more than 400 megawatts of batteries operating, meaning individual projects elsewhere in the country contain more battery capacity than is in the entirety of the nation’s largest wholesale market.

Beyond the limited regulation market, PJM’s rules and market dynamics make it hard for developers to finance storage projects. In California and Texas, battery owners can profit by charging up at times when solar generation makes grid power very cheap and selling back to the grid when prices are high. But PJM doesn’t experience that level of daily swing from cheap to expensive power, Hoos said.

Battery developers could try to make money instead by committing their batteries in the capacity auction. However, PJM awards capacity contracts on a one-year basis, which prevents developers from locking down long-term revenue certainty, like they can in California.

Aurora modeled a hypothetical four-hour duration battery in Virginia and found that half its revenue would come from capacity payments and half from energy arbitrage. But, Hoos added, “the revenue from both of those is still not enough for an investor to build a merchant battery.”

Prospect Power could be the project that breaks the dry spell, and it’s taken many hands to make that possible.

Storage specialist Eolian Energy, known for its pioneering battery construction in Texas, started developing the project back around 2017 in a joint venture with Open Road Renewable Energy. Eolian CEO Aaron Zubaty wanted to place a project “anywhere we could within a 100-mile radius of northern Virginia to feed the data center load growth.” But Data Center Alley is ringed by rolling Virginia horse country, where landowners were not enthusiastic about power plant construction.

The joint venture ended up securing a parcel farther west, over the Blue Ridge Mountains, that could ship power directly to northern Virginia. In 2023, the joint venture sold the project to Swift Current Energy, which secured a 15-year contract from utility Dominion Energy. That dependable revenue stream helped Swift Current lock down a $242 million financing package last September to build the project.

Now, Elevate has emerged as the long-term owner, which will operate the finished battery just in time to navigate the choppy waters of PJM amid the AI boom.

The Prospect battery broke through the PJM logjam because state policy created an opening.

PJM governs the energy markets for the whole region, but individual states can layer on their own policies, and Virginia passed a comprehensive clean energy law in 2020. This law sets a 100% renewable electricity target and requires Dominion, the largest utility in the state, to procure 2.7 gigawatts of energy storage by 2035, some of which must be owned by third parties.

Virginia also has long been home to the densest cluster of data centers in the world, stemming from Cold War defense investments that kick-started a dense fiber-optic network there. That has naturally evolved into ground zero for AI computing investment, which is putting utilities in a bind as they try to figure out how to deliver enough power for the new computing behemoths.

“There is a need for capacity, and the states are stepping up to incent that battery capacity to come online, to drive affordability and reliability,” Elevate’s Rogol said.

Prospect checks off part of Dominion’s energy storage obligation under state law, and it delivers a powerful tool for meeting Data Center Alley’s needs during peak hours, when the grid might struggle.

As for what the battery will do exactly, the short answer is, whatever Dominion asks for. Under the contract, known as a tolling agreement, Elevate will own the battery and keep it in fine working condition, Rogol said, while Dominion will dispatch it to monetize regulation, energy arbitrage, and capacity as it sees fit.

The conditions that made Prospect possible, then, aren’t in place across most of PJM’s territory, though the PJM states of Illinois, New Jersey, and Maryland have enacted policies that support storage build-out, too. Prospect may be a lonely giant for a few more years, but the sheer need for more capacity should change that sooner or later.

“With limited availability of gas turbines; constraints on gas fuel supply; challenges siting, permitting, and building new gas plants; and a limited number of gas plants in advanced development, it is difficult to see how growing demand in PJM will be met anytime soon without a lot of storage filling the gap,” said Brent Nelson, managing director of markets and strategy at the research firm Ascend Analytics. “But mechanisms to provide stable revenues will be critical for getting projects financed and built.”

When the PJM region figures out those mechanisms, Zubaty expects the situation to improve.

“It’s evolving very quickly,” he said of the storage market in PJM. “I think people are going to be surprised. It’s going to go from being totally dead to seeing a huge amount of build.”

This story was originally published by Capital B, a nonprofit newsroom that centers Black voices and experiences. To read more of Adam Mahoney’s work, visit Capital B.

In December, on a two-lane road not far from the ACE Basin, a protected ecosystem and wildlife refuge in South Carolina, Paul Black drove past St. Paul AME Church and the cemetery where his wife’s grandfather, great-grandfather, and great-grandmother are buried, then slowed as the trees opened onto the piney tract.

Black is an environmental activist who has spent years fighting polluting projects across the South. But now he and Black residents in a rural South Carolina community are bracing for a new fight: to stop a proposed data center complex the size of 1,200 football fields.

This specific project in Colleton County would be one of the largest in the South, and only came to the area after developers tried — and failed — to build a similar campus in a predominantly white county in Georgia.

Black imagined a world where the generational rituals of rural life — raising livestock, growing food, and fishing — would cease to exist because of the proposed nine data centers and two substations that would replace woods and wetlands.

“All too often, these polluting industries and questionable zoning decisions land in Black and brown communities, places that are least empowered and have already carried the burden of past pollution,” he said.

The fight for this Black community is being waged on multiple fronts. In addition to this data center, residents are bracing for a controversial new $5 billion gas power plant and pipeline needed to keep the data center on. At the same time, President Donald Trump has directed federal agencies to fast-track building AI data centers on contaminated sites deemed too toxic for development without years of cleanup, including one not too far from the community.

The proposal for this campus on timberland and wetlands is part of a broader build-out of power-hungry facilities across South Carolina.

To serve this new energy demand, two power companies, Santee Cooper and Dominion Energy South Carolina, are pushing for the new gas plant on the banks of the Edisto River in Colleton County. The power plant project’s cost has already doubled to $5 billion, and environmental advocates warn that it will threaten air quality, water, and critical habitats.

Given that the developers — Thomas & Hutton and Eagle Rock Partners, working on behalf of timber giant Weyerhaeuser — were willing to move this project to a poorer, Blacker area after opposition in Georgia, residents say this fight is about more than land. It is a test of who is asked to bear the risks of the data and AI boom, and what South Carolina is willing to sacrifice to power it.

“If a mostly white community can push back on this project and get it stopped, it’s unacceptable that the next move is to fly under the radar in a rural Black community with even less transparency,” Black added.

For organizers like Black, the ACE Basin fight is part of a much larger pattern they’ve been battling for generations.

For years, Black residents and their allies have fought to force the federal government to clean up the country’s most contaminated sites, known as Superfund sites, and to expand the funding for such work. It is a part of the environmental justice movement, born from Black and low-income communities locked into neighborhoods next to refineries, landfills, and nuclear facilities that whiter, wealthier areas kept out.

Now, in a sharp turn, the Trump administration wants to build data centers on these sites with lower environmental regulations for cleanup.

About 100 miles inland from where Colleton County residents are fighting this massive data campus, the Trump administration has tapped a former nuclear weapons complex in the Savannah River area — where workers recently discovered a radioactive wasp nest — as one of four flagship locations for new AI data centers and energy projects.

“They’re trying to expand use of the land for things that are extraneous to the cleanup mission, which is the most important thing going on out there,” said longtime watchdog Tom Clements, who has tracked federal nuclear policy in South Carolina for decades.

To environmental justice advocates watching both the ACE Basin fight and the Savannah River announcement, the move feels like a betrayal of those hard-won cleanups, repackaging sacrifice zones as prime real estate for the AI boom while communities are still grappling with contamination and long-term health risks.

“There’s a lot of national narrative around AI and data centers, but on the ground these fights are very simple: who gets sacrificed, and whose communities are treated as expendable,” said Robby Maynor, a climate campaign associate at the Southern Environmental Law Center.

The proposed gas plant needed for the Colleton County data center campus could result in more than $30 million in local health care costs as residents begin to struggle through respiratory illnesses, according to a pollution analysis by the Southern Environmental Law Center.

The pollution from gas power plants, fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5, can penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream, causing respiratory and cardiovascular disease. It is linked to asthma attacks, strokes, dementia, and cancer.

Black Americans have the highest death rate from such pollution in the U.S.

The data centers themselves add another layer of health risk. Each facility relies on diesel backup generators that are tested regularly and can be operated during grid emergencies. Diesel exhaust contains the same fine particle pollution emitted by gas power plants.

But under federal rules, data centers face no time limits on diesel generator use during declared emergencies, and operators are typically required only to self-report their emissions.

“We believe there are cleaner, smarter, less risky ways to meet South Carolina’s energy needs,” said Eddy Moore, decarbonization director at the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy.

Researchers examining air pollution near EPA-regulated data centers found that approximately 4 million people live within 1 mile of these facilities, exposing them to elevated levels of diesel exhaust and other pollutants.

The researchers found that the communities closest to data centers are “overwhelmingly” non-white.

On the evening of Dec. 16, residents packed into Emmanuel Baptist Church, a small white building just down the road from the proposed data center site. The church had coordinated with St. Paul AME and three other nearby Black churches to ensure word spread through the community.

Many who gathered had learned about the proposal only a week earlier. They came with questions about water — whether the data centers would drain the aquifer that feeds their private wells — and about noise, light pollution, and whether their property values would plummet. Others questioned where their family cemeteries sat in relation to the site boundaries.

A local pastor told Black, the environmental activist, he’d heard nothing about the project until Black called him, even though his church sits within sight of the proposed campus.

Jennifer Singleton, a resident who lives near the site, said the lack of transparency feels deliberate. “There’s a better place for this if it has to happen other than in a rural community,” she said. “This thing deserves a fight because it doesn’t need to be here.”

At the meeting, organizers explained that the developers are seeking a special exception to build on land zoned for rural development. The county’s own comprehensive plan designates the area as “countryside” that should be preserved.

“People in Colleton County are being told they’ll pay for this power plant, breathe its pollution, and then live next to data centers that aren’t even legally meant to be here,” Maynor said.

“For a community that had almost no time to get up to speed,” Black added, “the response has been proportionate to the threat. People are rallying because this is an existential threat to their community.”