Nearly 10 years after Massachusetts announced plans to buy 1.2 gigawatts of carbon-free hydropower from Canada, the clean electrons are finally set to start flowing into the state.

As soon as this Friday, the New England Clean Energy Connect transmission line could begin commercial operations.

The 145-mile project, extending from the Canadian border to the southern Maine city of Lewiston, will function as something like an enormous extension cord, plugging the New England grid into a supply of electricity generated by energy giant Hydro-Québec. The new supply is expected to save the average residential customer in Massachusetts $18 to $20 per year and move the state closer to its goal of net-zero emissions by 2050.

“This is a significant moment for clean energy in New England,” said Phelps Turner, director of clean grid for the Conservation Law Foundation.

Avangrid, the developer of the transmission line, told Maine utility regulators earlier this month that operations are scheduled to begin on Jan. 16. Work is underway to meet that target.

“Teams are busy on both sides of the U.S.-Canada border,” said Hydro-Québec spokesperson Lynn St-Laurent. “We have been actively testing the equipment for the past several weeks.”

Following a tumultuous year for clean energy projects, the completion of the controversial transmission line is both a rare triumph and a case study in the challenges of balancing decarbonization and the preservation of wild lands. It’s also an uncommon example of transmission getting built in the U.S., where it has proven difficult to construct the massive power lines needed to deliver new electricity supply to population centers.

The project has its roots in a 2016 Massachusetts law that called for the state to procure 1.2 gigawatts of Canadian hydropower, or other renewables, and 1.6 gigawatts of offshore wind energy. The first idea for importing power from the north involved working with a planned 192-mile transmission line through New Hampshire. However, the project was scuttled in 2019 by public outcry against the prospect of chopping a path through some of the state’s treasured forests.

Massachusetts then looked east, to Maine, to find a route for the transmission line. Similar objections quickly arose, with opponents in the state filing a series of legal challenges. In 2021, Maine voters approved a ballot referendum effectively blocking the project. Work froze until August 2023, a few months after a jury unanimously ruled the project could move forward.

The delays spiked the project’s price tag. Before the line could start providing power, the developer, state regulators, and utilities had to come to an agreement about how those costs would be covered. In early 2025, they settled on terms that increased the price utilities would pay by a total of about $521 million, but ensured consumers would still see savings.

“The project faced many challenges over many years, and it survived all of them,” Turner said.

In addition to the modest monthly savings expected for Massachusetts utility customers, the influx of hydropower should keep rates down for consumers throughout New England by pouring lower-cost electricity into the market that will put downward pressure on prices, right at a time when rising energy bills have become a major issue, Turner said.

Questions remain, however, about how much new power the project will actually bring to the New England grid.

Hydro-Québec already sends power into the region on a separate transmission line, though these exports have decreased in recent years, even stopping almost entirely for a period in 2025. It’s possible that meeting its commitment to deliver along the New England Clean Energy Connect line will mean Hydro-Québec chooses to send less power along other pathways, said Dan Dolan, president of regional trade group the New England Power Generators Association. The net increase in clean power may be lower than anticipated.

“The change in flows over the last several years, particularly in 2025, do not leave me optimistic that Canadian hydro is here to save the day,” Dolan said.

Voters worried about rising electricity prices and the onslaught of power-hungry data centers helped Democrats earn a governing trifecta in Virginia last year.

Now, as state lawmakers prepare for a breakneck, 60-day legislative session that begins this Wednesday, clean energy is emerging as a key strategy for dealing with those challenges.

“Oftentimes, I go into a legislative session sort of just guessing what people are going to care about,” said Kendl Kobbervig, advocacy and communications director for the nonprofit Clean Virginia. Not this year, she said. “No. 1 is affordability, and second is data center reform.”

The concerns come as Virginia, the world’s data center capital, is at a crossroads on its quest for 100% clean energy. The commitment began in earnest in 2020, when the state enacted a measure requiring its two investor-owned utilities — Dominion Energy and Appalachian Power Co. — to convert to carbon-free electricity by midcentury. The law also prevents new construction of fossil fuel–burning plants, with some exceptions.

But the landscape has changed dramatically over the last five years, with Dominion now projecting enormous electricity demand from the 663 data centers in the state, and counting. The company has used those predictions to justify building a spate of new gas plants over the next decade, starting with a 944-megawatt complex in Chesterfield County, just southwest of Richmond. Though regulators are taking a second look at the controversial new plant, they’ve mostly blessed the company’s plans. At the same time, Dominion warns that President Donald Trump’s move to halt construction of its Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind Project, with a projected 2.6 gigawatts of capacity, could constrain supply.

These demand pressures are one reason Virginians face rising energy bills.

Dominion, the state’s largest utility, won approval last November for a roughly 9% increase in residential rates over the next two years in a ruling that advocates say didn’t do enough to ensure that data centers pay their fair share of costs. Customers of Appalachian Power, in the southwest corner of the state, have already seen a spike in their bills, driven in substantial part by the escalating price of gas and coal.

Republicans and even some Democrats have said the way to cost-effectively meet ballooning power needs is to back away from the clean energy transition and the 2020 law, the Virginia Clean Economy Act. But multiple Democratic lawmakers are pushing bills this year that do just the opposite in an effort to save consumers money and increase electricity generation.

“The name of the game this session is affordability,” Democrat Del. Phil Hernandez of Norfolk said at a news conference last week.

One proposal to lower costs, offered by Hernandez and Sen. Schuyler VanValkenburg of Henrico, is dubbed the Facilitating Access to Surplus Transmission, or FAST, Act.

The bill is made possible by a new rule at PJM Interconnection, the multistate entity that manages Virginia’s grid: Facing lengthy backlogs for new grid hookups, PJM said last year it could connect some sources on an expedited basis so long as they didn’t trigger meaningful upgrades to the transmission grid.

“There are miles and miles of our current transmission infrastructure that are not being used at nearly their full capacity,” said Jim Purekal, a director at Advanced Energy United who heads the organization’s legislative work in Virginia. “A traditional peaker plant only operates at various points around the year. The rest of the time, it’s essentially dormant.”

The FAST Act, Hernandez said, “will lay out a process to help get these new energy projects up and running.”

The PJM surplus interconnection rule is a permission structure, not a mandate. And utilities may be tempted to use the regulation to build expensive new fossil fuel plants. The bill would set up a study of how much headroom is on the grid and create a procedure to allow only the most cost-effective resources to utilize it.

“Let’s make sure that if you’re going to be using this capacity,” Purekal said, “you’re using the most affordable assets on the commercial market today: solar, onshore wind, and battery storage.”

Advanced Energy United expects 2 to 3 gigawatts of such resources could be colocated with existing power plants of all types within four years. That’s about two times faster than it has taken a project to get through PJM’s queue in recent years.

“We believe this could be one of the fastest, lowest-cost ways to add power to the grid,” Hernandez said.

A complementary effort, to be introduced by Sen. Lamont Bagby of Richmond and Del. Rip Sullivan of Fairfax, would increase grid battery targets in the 2020 law and help ensure energy storage projects are cost-effective for ratepayers.

With Hernandez, the lawmakers promoted it at last week’s press event behind a podium sign that read, “Energy Storage Keeps Electricity Affordable.” One reason that’s true, Sullivan noted at the conference, is that batteries can charge when electricity prices are low and supply is abundant — as on a mild, sunny afternoon — and discharge when demand is high and hourly prices go up. “We can store energy when it’s cheap,” he said, adding that “this is the best energy storage bill in the country.”

The storage and surplus interconnection bills aren’t the only pieces of legislation on Democrats’ affordability agenda.

Indeed, incoming Del. Lily Franklin of southwest Virginia is among those seeking to bring costs down for customers of Appalachian Power, in part by reining in transmission and fuel charges that typically get less scrutiny in rate cases.

Likewise, Sullivan and Sen. Scott Surovell of Fairfax will proffer legislation to lay the groundwork for a ratemaking scheme that would align utilities’ profits with their performance on clean energy, efficiency, and affordability. Among others, the measure was recommended last month by the influential Commission on Electric Utility Regulation, which Surovell chairs.

The stamp of approval may help the measure’s chances in the legislature this year, as should its lead patron. “Sen. Surovell is the Senate majority leader,” Kobbervig said. “So when he says yes to things, you think, ‘OK, this has legs!’”

The other thorny problem at the top of lawmakers’ energy agenda is the explosive growth of data centers in the state. According to Dominion, the facilities could account for an eyepopping 51% of its electricity sales by 2035, though such figures are notoriously slippery.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty in this market. There’s a lot of speculative load,” said Nate Benforado, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center. “At the same time, that is an astounding number.”

Environmental advocates’ plan to confront the challenges posed by data centers includes sticks such as increasing transparency on utility projections and ensuring that residential customers aren’t unfairly burdened with increased costs. But Sullivan and Sen. Creigh Deeds of Charlottesville also want to reform a sizable carrot: the generous tax incentives that lured Amazon, Google, and their ilk to the state in the first place.

“It’s by far Virginia’s largest tax break, and it’s going to some very large companies,” Benforado said. That’s part of why its conditions should include investments in renewables and efficiency.

“We want to only give a tax incentive to data centers that are accelerating the clean energy transition — and certainly not hurting that transition.”

Several of the measures Democrats plan in 2026 cleared the General Assembly last year, only to be vetoed by outgoing Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican.

But on Jan. 17, Youngkin will be replaced by Gov.-elect Abigail Spanberger, a Democrat who campaigned on affordability and data center growth, and has already championed the bill to increase the state’s battery storage targets, among other measures.

“I recognize the complexity of our current challenges and threats posed by the future demands, but the answer is not to sit so our problems only get worse,” Spanberger said at a news conference last month about her energy agenda, according to the Virginia Mercury.

Still, Republicans have sought for years to weaken or repeal the 2020 Clean Economy Act, and the onslaught of data centers, community concern over large-scale solar farms, and the Trump administration’s anti-renewables stance are breathing new life into their arguments.

At the same time, powerful Democrats, including Surovell and House of Delegates Speaker Don Scott of Portsmouth, haven’t ruled out relaxing the law’s prohibitions on new gas plants, according to Inside Climate News. Dominion has asserted that such plants are needed to keep the lights on in the face of new demand.

Clean energy advocates plan to forcefully rebut those claims in the General Assembly and the public square.

“It is incumbent on us to be pushing back on the concepts that gas is clean, that gas is affordable, that it’s the only way to have a reliable grid,” said Benforado. “They are simply not true.”

The mid-Atlantic grid operator PJM Interconnection faces a capacity crunch of titanic proportions as AI computing investment rushes headlong into its 13-state region, home to more than 67 million people. The most recent PJM capacity auctions — where the grid operator pays in advance for power plants to be available to serve the grid — hit record-high clearing prices in December, portending more expensive electricity for the region.

The developer Elevate Renewables is tackling that dire need by accomplishing something unheard of in the PJM region: building a really big battery. The company, launched by private equity firm ArcLight in 2022, announced today that it had acquired a 150-megawatt/600-megawatt-hour battery project in northern Virginia and will complete construction by mid-2026. Called Prospect Power, the project could be bolstering the grid near the state’s famed “Data Center Alley” just in time for the summer spike in electricity use.

“The states want capacity, they want affordability, they want in-state resources,” Elevate CEO Joshua Rogol told Canary Media. “Storage can clearly be part of the solution to that problem. It is one of the few resources that can come online quickly, given how long it takes to develop and build a project given the supply chain as it exists today.”

Fossil gas still generates more power across the U.S. than any other resource, but battery storage has become the top source of on-demand power being built today (solar, as an intermittent producer, does not meet that definition).

However, almost all the storage action, and its resulting benefits, has happened in California and Texas. Data firm Modo Energy drew the comparison in a report last year: “In the past five years, PJM has added just 200 MW of grid-scale battery capacity — while Texas and California have cumulatively built more than 20 GW of [battery energy storage systems] over the same period.” It’s as if a major swath of the country saw a few states adopting smartphones and said, “No, thanks, we’re happy with flip phones.”

PJM’s failure to keep up with this particular grid technology is particularly surprising because PJM actually created the modern storage market back in 2012, by letting batteries compete for the rapid-fire grid service known as frequency regulation. Those rules spurred a buildout of 181 megawatts by 2016, according to Modo — heady stuff at the time, and well before storage in California and Texas took off. But these batteries tended to have just 15 minutes of duration, because that’s all that was needed to perform that role for the grid.

“The economic strategy was always to build a very short-duration battery, just participate in regulation services and make really substantial returns that way,” said Julia Hoos, head of USA East at Aurora Energy Research.

Frequency regulation has stayed lucrative for battery owners, Hoos noted, in part due to quirks in PJM’s rules that reserved some of the market for thermal generators like gas plants, which set a higher clearing price than batteries do. But rule changes now underway will likely reduce the payoff in future years.

In any case, the amount of regulation PJM needs for the grid isn’t enough to support a larger battery buildout on its own. Currently, PJM has more than 400 megawatts of batteries operating, meaning individual projects elsewhere in the country contain more battery capacity than is in the entirety of the nation’s largest wholesale market.

Beyond the limited regulation market, PJM’s rules and market dynamics make it hard for developers to finance storage projects. In California and Texas, battery owners can profit by charging up at times when solar generation makes grid power very cheap and selling back to the grid when prices are high. But PJM doesn’t experience that level of daily swing from cheap to expensive power, Hoos said.

Battery developers could try to make money instead by committing their batteries in the capacity auction. However, PJM awards capacity contracts on a one-year basis, which prevents developers from locking down long-term revenue certainty, like they can in California.

Aurora modeled a hypothetical four-hour duration battery in Virginia and found that half its revenue would come from capacity payments and half from energy arbitrage. But, Hoos added, “the revenue from both of those is still not enough for an investor to build a merchant battery.”

Prospect Power could be the project that breaks the dry spell, and it’s taken many hands to make that possible.

Storage specialist Eolian Energy, known for its pioneering battery construction in Texas, started developing the project back around 2017 in a joint venture with Open Road Renewable Energy. Eolian CEO Aaron Zubaty wanted to place a project “anywhere we could within a 100-mile radius of northern Virginia to feed the data center load growth.” But Data Center Alley is ringed by rolling Virginia horse country, where landowners were not enthusiastic about power plant construction.

The joint venture ended up securing a parcel farther west, over the Blue Ridge Mountains, that could ship power directly to northern Virginia. In 2023, the joint venture sold the project to Swift Current Energy, which secured a 15-year contract from utility Dominion Energy. That dependable revenue stream helped Swift Current lock down a $242 million financing package last September to build the project.

Now, Elevate has emerged as the long-term owner, which will operate the finished battery just in time to navigate the choppy waters of PJM amid the AI boom.

The Prospect battery broke through the PJM logjam because state policy created an opening.

PJM governs the energy markets for the whole region, but individual states can layer on their own policies, and Virginia passed a comprehensive clean energy law in 2020. This law sets a 100% renewable electricity target and requires Dominion, the largest utility in the state, to procure 2.7 gigawatts of energy storage by 2035, some of which must be owned by third parties.

Virginia also has long been home to the densest cluster of data centers in the world, stemming from Cold War defense investments that kick-started a dense fiber-optic network there. That has naturally evolved into ground zero for AI computing investment, which is putting utilities in a bind as they try to figure out how to deliver enough power for the new computing behemoths.

“There is a need for capacity, and the states are stepping up to incent that battery capacity to come online, to drive affordability and reliability,” Elevate’s Rogol said.

Prospect checks off part of Dominion’s energy storage obligation under state law, and it delivers a powerful tool for meeting Data Center Alley’s needs during peak hours, when the grid might struggle.

As for what the battery will do exactly, the short answer is, whatever Dominion asks for. Under the contract, known as a tolling agreement, Elevate will own the battery and keep it in fine working condition, Rogol said, while Dominion will dispatch it to monetize regulation, energy arbitrage, and capacity as it sees fit.

The conditions that made Prospect possible, then, aren’t in place across most of PJM’s territory, though the PJM states of Illinois, New Jersey, and Maryland have enacted policies that support storage build-out, too. Prospect may be a lonely giant for a few more years, but the sheer need for more capacity should change that sooner or later.

“With limited availability of gas turbines; constraints on gas fuel supply; challenges siting, permitting, and building new gas plants; and a limited number of gas plants in advanced development, it is difficult to see how growing demand in PJM will be met anytime soon without a lot of storage filling the gap,” said Brent Nelson, managing director of markets and strategy at the research firm Ascend Analytics. “But mechanisms to provide stable revenues will be critical for getting projects financed and built.”

When the PJM region figures out those mechanisms, Zubaty expects the situation to improve.

“It’s evolving very quickly,” he said of the storage market in PJM. “I think people are going to be surprised. It’s going to go from being totally dead to seeing a huge amount of build.”

A debate playing out in Wisconsin underscores just how challenging it is for U.S. states to set policies governing data centers, even as tech giants speed ahead with plans to build the energy-gobbling computing facilities.

Wisconsin’s state legislators are eager to pass a law that prevents the data center boom from spiking households’ energy bills. The problem is, Democrats and Republicans have starkly different visions for what that measure should look like — especially when it comes to rules around hyperscalers’ renewable energy use.

Republican state legislators introduced a bill last week that orders utility regulators to ensure that regular customers do not pay any costs of constructing the electric infrastructure needed to serve data centers. It also requires data centers to recycle the water used to cool servers and to restore the site if construction isn’t completed.

Those are key protections sought by decision-makers across the political spectrum, as opposition to data centers in Wisconsin and beyond reaches a fever pitch.

But the bill will likely be doomed by a “poison pill,” as consumer advocates and manufacturing-industry sources describe it, that says all renewable energy used to power data centers must be built on-site.

Republican lawmakers argue this provision is necessary to prevent new solar farms and transmission lines from sprawling across the state.

“Sometimes these data centers attempt to say that they are environmentally friendly by saying we’re going to have all renewable electricity, but that requires lots of transmission from other places, either around the state or around the region,” said State Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, a Republican, at a press conference this week. “So this bill actually says that if you are going to do renewable energy, and we would encourage them to do that, it has to be done on-site.”

This effectively means that data centers would have to rely largely on fossil fuels, given the limited size of their sites and the relative paucity of renewable energy in the state thus far.

Gov. Tony Evers and his fellow Democrats in the state legislature are unlikely to agree to this scenario, Wisconsin consumer and clean-energy advocates say.

Democrats introduced their own data center bill late last year, some of which aligns closely with the Republican measure: The Democratic bill would similarly block utilities from shifting data center costs onto residents, by creating a separate billing class for very large energy customers. It would require that data centers pay an annual fee to fund public benefits such as energy upgrades for low-income households and to support the state’s green bank.

But that proposal may also prove impossible to pass, advocates say, because of its mandate that data centers get 70% of their energy from renewables in order to qualify for state tax breaks, and a requirement that workers constructing and overhauling data centers be paid a prevailing wage for the area. This labor provision is deeply polarizing in Wisconsin. Former Republican Gov. Scott Walker and lawmakers in his party famously repealed the state’s prevailing-wage law for public construction projects in 2017, and multiple Democratic efforts to reinstate it have failed.

The result of the political division around renewables and other issues is that Wisconsin may accomplish little around data center regulation in the near term.

“If we could combine the two and make it a better bill, that would be ideal,” said Beata Wierzba, government affairs director for the nonprofit clean-energy advocacy group Renew Wisconsin. “It’s hard to see where this will go ultimately. I don’t foresee the Democratic bill passing, and I also don’t know how the governor can sign the Republican bill.”

Wisconsin’s consumer and clean energy advocates are frustrated about the absence of promising legislation at a time when they say regulation of data centers is badly needed. The environmental advocacy group Clean Wisconsin has received thousands of signatures on a petition calling for a moratorium on data center approvals until a comprehensive state plan is in place.

At least five new major data centers are planned in the state, which is considered attractive for the industry because of its ample fresh water and open land, skilled workers, robust electric grid, and generous tax breaks. The Wisconsin Policy Forum estimated that data centers will drive the state’s peak electricity demand to 17.1 gigawatts by 2030, up from 14.6 gigawatts in 2024.

Absent special treatment for data centers, utilities will pass the costs on to customers for the new power needed to meet the rising demand.

Two Wisconsin utilities — We Energies and Alliant Energy — are proposing special tariffs that would determine the rates they charge data centers. Allowing utilities in the same state to have different policies for serving data centers could lead to these projects being located wherever utilities offer them the cheapest rates, and result in a patchwork of regulations and protections, consumer advocates argue. They say legislation should be passed soon, to standardize the process and enshrine protections statewide before utilities move forward on their own.

Some of Wisconsin’s neighbors have already taken that step, said Tom Content, executive director of Wisconsin’s Citizens Utility Board, a consumer advocacy group.

He pointed to Minnesota, where a law passed in June mandates that data centers and other customers be placed in separate categories for utility billing, eliminating the risk of data center costs being passed on to residents. The Minnesota law also protects customers from paying for “stranded costs” if a data center doesn’t end up needing the infrastructure that was built to serve it.

Ohio, by contrast, provides a cautionary tale, Content said. After state regulators enshrined provisions that protected customers of the utility AEP Ohio from data center costs, developers simply looked elsewhere in the state.

“Much of the data center demand in Ohio shifted to a different utility where no such protections were in place,” Content said. “We’re in a race to the bottom. Wisconsin needs a statewide framework to help guide data center development and ensure customers who aren’t tech companies don’t pick up the tab for these massive projects.”

Limiting clean energy construction to data center sites could be especially problematic, as data center developers often demand renewable energy to meet their own sustainability goals.

For example, the Lighthouse data center — being developed by OpenAI, Oracle, and Vantage near Milwaukee — will subsidize 179 megawatts of new wind generation, 1,266 megawatts of new solar generation, and 505 megawatts of new battery storage capacity, according to testimony from one of the developers in the We Energies tariff proceeding.

But Lighthouse covers 672 acres. It takes about 5 to 7 acres of land to generate 1 megawatt of solar energy, meaning the whole campus would have room for only about a tenth of the solar the developers promise.

We Energies is already developing the renewable generation intended to serve that data center, a utility spokesperson said, but the numbers show how future clean energy could be stymied by the on-site requirement.

“It’s unclear why lawmakers would want to discriminate against the two cheapest ways to produce energy in our state at a time when energy bills are already on the rise,” said Chelsea Chandler, the climate, energy, and air program director at Clean Wisconsin.

Renew Wisconsin’s Wierzba said the Democrats’ 70% renewable energy mandate for receiving tax breaks could likewise be problematic for tech firms.

“We want data centers to use renewable energy, and companies I’m aware of prefer that,” she said. “The way the Republican bill addresses that is negative and would deter that possibility. But the Democratic bill almost goes too far — 70%. That’s a prescribed amount, too much of a hook and not enough carrot.”

Alex Beld, Renew Wisconsin’s communications director, said the Republican bill might have a hope of passing if the poison pill about on-site renewable energy were removed.

“I don’t know if there’s a will on the Republican side to remove that piece,” he said. “One thing is obvious: No matter what side of the political aisle you’re on, there are concerns about the rapid development of these data centers. Some kind of legislation should be put forward that will pass.”

Bryan Rogers, environmental director of the Milwaukee community organization Walnut Way Conservation Corp, said elected officials shouldn’t be afraid to demand more of data centers, including more public benefit payments.

“We know what the data centers want and how fast they want it,” he said. “We can extract more concessions from data centers. They should be paying not just their full way — bringing their own energy, covering transmission, generation. We also know there are going to be social impacts, public health, environmental impacts. Someone has to be responsible for that.”

Utility representatives expressed less urgency around legislation.

William Skewes, executive director of the Wisconsin Utilities Association, said the trade group “appreciates and agrees with the desire by policymakers and customers to make sure they’re not paying for costs that they did not cause.”

But, he said, the state’s utility regulators already do “a very thorough job reviewing cases and making sure that doesn’t happen. Wisconsin utilities are aligned in the view that data centers must pay their full share of costs.”

If Wisconsin legislators do manage to pass data center legislation this session, it will head to the desk of Evers. The governor is a longtime advocate for renewables, creating the state’s first clean energy plan in 2022, and he has expressed support for attracting more data centers to Wisconsin.

“I personally believe that we need to make sure that we’re creating jobs for the future in the state of Wisconsin,” Evers said at a Monday press conference, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “But we have to balance that with my belief that we have to keep climate change in check. I think that can happen.”

The Trump administration wants PJM Interconnection, the country’s biggest power market, to force data center developers to pay directly for the new power plants they need. It’s the latest attempt to curb skyrocketing energy costs for the roughly 67 million people PJM serves from Virginia to Illinois.

On Friday, the National Energy Dominance Council and governors of some PJM states released an agreement that urges the grid operator to take action to solve its massive affordability and grid-reliability problems.

Specifically, it presses PJM to speed up the construction of more than $15 billion worth of “reliable baseload” power plants by providing them with 15 years of revenue certainty. It also directs PJM to “require data centers to pay for the new generation built on their behalf — whether they show up and use the power or not.”

But industry experts warned that these demands would be difficult, if not impossible, to execute fast enough to make a difference for the region.

“It’s not at all clear how this can actually get implemented,” Rob Gramlich, president of consultancy Grid Strategies, told Canary Media. “How would this ever get implemented — and would this require changes that usually take five years?”

The vision, according to an anonymous White House official quoted by Bloomberg, is to require PJM to set up an emergency auction by September, which would compel data centers and other “large loads” to pony up the $15 billion to spur new power plant construction.

PJM is already under a December order from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to overhaul its rules for how massive data centers can interconnect to its grid.

The grid operator has also been slowly working on reform of its own. Its monthslong effort to get stakeholders — including utilities, power plant owners, big corporate energy users, data center developers, and consumer advocates — to agree on new structures to deal with the rising cost impacts of data centers ended in deadlock late last year. In a twist of fate, PJM released its decision on this matter later on Friday.

That plan has not yet been reconciled against the Trump administration’s just-released principles — PJM itself was not invited to the Friday White House event at which the agreement was announced, spokesperson Jeffrey Shields told Bloomberg.

Now, “PJM is reviewing the principles set forth by the White House and governors,” Shields said in a statement to Canary Media. “We will work with our stakeholders to assess how the White House directive aligns with the [large-load plan].”

The agreement’s goal is ultimately to curb PJM’s skyrocketing capacity costs, which are driven by the grid operator’s inability to build new generation or energy storage capacity fast enough to meet booming demand.

PJM’s rising utility rates are driving backlash from consumers — and demands from politicians to take action, including limiting data center growth.

“The principle of new large loads paying their fair share is gaining consensus across states, industry groups, and political parties,” Gramlich said. “The rules that have been in place for years did not ensure that.”

But Gramlich highlighted that Friday’s plan will run into the same state-vs.-federal jurisdictional conflicts that have stymied PJM’s efforts to reform data-center interconnection to date.

First off, PJM’s capacity auctions operate by allowing power plants, battery projects, demand-response providers, and other “supply-side” providers to bid their capacity into the system. Those capacity costs are then passed along to utilities, he noted. Utility customers themselves — including data centers — are not part of that equation.

“Even if the large loads voluntarily participate, there’s no mechanism currently for direct participation of a retail customer in a wholesale auction,” Gramlich said.

What’s more, data centers remain customers of utilities regulated at the state level. “It might require changes in state law in any PJM state” to alter those facts, he said.

Even if such state policies were put in place, there’s no guarantee that the prospective data centers would play ball, he said. “It’s easy to hold an auction, but the hard part is compelling anyone to participate.”

The new agreement faces other fundamental challenges, too.

While the text doesn’t specify the exact type of power plants it wants PJM to build, its call for “reliable baseload power generation” is code for fossil fuels or nuclear power. That will pose problems. Demand for gas turbines has pushed delivery orders for new power plants out to 2028 or later. Almost all of the new gas-fired power plants secured in PJM’s fast-track procurement last year aren’t set to come online until 2030 or later. And nuclear power plants usually take about a decade to build.

Meanwhile, more than 100 gigawatts of potential new grid resources, the vast majority of which are solar, wind, and batteries, remain stuck in PJM’s badly congested interconnection queue. PJM is still working on efforts to fast-track these resources by, for example, pairing batteries with existing solar and wind farms.

Ultimately, an auction of the kind the White House plan envisions could drive investment in more power plants, according to Julia Hoos, head of USA East at Aurora Energy Research — but it could also “exacerbate some other elements of PJM’s challenges.”

“Everyone agrees that PJM is struggling to bring online new generation fast enough, and that some sort of intervention is required,” Hoos wrote in a Friday email. But she added that “PJM already has several ongoing reform processes to address these issues — and it’s pretty unprecedented for this sort of top-down intervention to direct PJM’s efforts.”

Almost a year ago, President Donald Trump declared that the United States was experiencing an “energy emergency.”

At the time, the U.S. was beating national and world-historical records for oil and gas production, as well as for wind and solar generation. But since then, the threat of an energy emergency really has emerged, in large part thanks to Trump’s own interventions in the power sector.

The Trump administration has blocked construction of renewable power sources, rescinded billions of dollars allocated by Congress to expand the grid and clean energy, and helped pass a law that vaporized federal tax credits for wind and solar projects.

These actions have compounded long-running challenges in connecting projects to the grid. All the while, the AI arms race — an avowed Trump priority — has pushed the need for new power production to dizzying heights.

Electricity demand will clearly outpace supply in the coming years, and concerted federal efforts are further reducing that supply. So, does that mean we are inevitably headed for an energy crisis? Nearly everyone I spoke with for this story believed the crisis was coming, if not already upon us.

“The mismatch just grows every day, with every new project cancellation and every new data center,” said Jesse Lee, a senior adviser at Climate Power, which advocates for action on climate change. “When you mismatch supply and demand that way, you get prices going through the roof.”

Indeed, residential electric utility rates rose by 13% from January to September of last year, and pressure on consumers became a major electoral issue in November’s gubernatorial elections in New Jersey and Virginia.

Longer term, the mismatch could result in regional energy shortfalls and threaten hundreds of billions of dollars in AI investment if the grid simply can’t keep up.

“Many parts of the country will have rolling blackouts in the next few years if we aren’t intentional about solving this crisis,” said Costa Samaras, who directs the Wilton E. Scott Institute for Energy Innovation at Carnegie Mellon University and worked on clean energy innovation in the Biden White House.

Somewhat dire stuff to kick off the new year with. But the very recognition of the problem is laying the groundwork for tackling it. And the looming menace of AI’s energy consumption just might deliver our best bet to convert energy scarcity into abundance.

This current energy predicament stands out from its predecessors because so many of the decisions constraining U.S. energy supply are being made domestically rather than by foreign adversaries.

Since resuming office, Trump has overseen continual supply-reducing moves, including:

“There is a crisis. It’s like we’re back in the ’70s, but instead of OPEC squeezing us, it’s us squeezing us,” said Armond Cohen, executive director of the Clean Air Task Force.

All told, 266 gigawatts of planned electricity generation projects fell through in 2025, according to analyst Michael Thomas. Thomas’ data platform, Cleanview, tracks more than 10,000 clean energy projects — a tricky task because developers often advance speculative projects to see if they can win a grid connection. But offshore wind tends to involve less speculation, given the hurdles to secure rights, Thomas said, and there’s been a clear trend of offshore wind cancellations this year in response to the administration’s hostility.

Other cancellations stem from issues that precede Trump’s directives, such as regional grid operators asking developers to pay exorbitant rates to connect to the network and local opposition blocking a project.

“So many of these challenges of how we build the necessary infrastructure to make the world better,” Thomas said, are “playing out county by county in these little battles of ‘Do we build a wind farm here, do we build a solar farm here?’”

Not all clean energy developments are under threat. The budget law Trump signed in July preserved Biden-era tax credits to install on-demand clean energy sources like batteries, geothermal, and nuclear, even as it did away with credits for wind and solar generation.

A Department of Energy spokesperson did not respond to questions about what the administration is doing about the declared energy crisis. The DOE has made some moves to expand electricity supply: It loaned $1 billion to help restart a nuclear reactor at Three Mile Island, and it kicked off a challenge to build new modular reactor designs by July 2026 — though these nascent technologies will take many years to secure regulatory approvals and enter commercial deployment.

Most intriguingly, Trump Media & Technology, the parent company of Trump’s own social media platform, Truth Social, announced in December that it would pursue a merger with nuclear fusion startup TAE Technologies. TAE hopes to generate clean baseload power in the early 2030s, though scientists consider cracking commercially viable fusion to be more technically challenging than running a niche and unprofitable social media platform.

Meanwhile, tech giants’ ambitions for AI computing construction have ballooned. Thomas said that while 20 to 30 gigawatts of data centers are operating today, 100 gigawatts are trying to connect in the next five years. Analysts at BloombergNEF predicted in December that data centers will consume 106 gigawatts by 2035; that number grew by 36% from the company’s tally just seven months prior.

Rep. Sean Casten, an Illinois Democrat and a leading energy wonk in Congress, said he worries about the current federal leadership’s capacity to respond to a full-blown energy crisis.

“Tell me how much volatility is coming down the pike, and it’s sort of like you’ve got a JV baseball team that’s working the ER shift tonight — if nobody checks into the ER, we’re gonna be fine,” he said.

Even so, Casten thinks widespread blackouts are a low-probability outcome because energy regulators have such a bias toward protecting reliability.

“The state utility commissions, the regional transmission organizations, they don’t always make good decisions, but they generally do prioritize reliability,” he said. “Having said that, the energy crisis that I think we should be super concerned about is on the price side.”

The Trump administration has raised the cost of energy not just by reducing supply. The delays it has caused for offshore wind projects have racked up hundreds of millions of dollars of unforeseen expenses, even before the most recent attempt to stop them from finishing construction. The interruptions also signal to foreign investors that billion-dollar projects in the U.S. are susceptible to extralegal disruption by the government, chilling future investment. Trump’s DOE has repeatedly invoked emergency powers to force old coal-fired plants to keep running beyond their planned retirement, leaving customers to foot the bill for tens, if not hundreds, of millions of dollars.

Those are system-level cost increases. On a more individual scale, when Republicans demolished the Inflation Reduction Act, they removed incentives for families to upgrade household energy efficiency, the Scott Institute’s Samaras noted. “Those save the homeowner money, but they also reduce the peak electricity demand when you really need it.”

The Trump administration could tackle the crisis by simply allowing American energy, including clean technologies, to flourish.

“Just get out of the way and stop blocking solar and wind permits,” said Shannon Baker-Branstetter, senior director of domestic climate and energy policy at the Center for American Progress. “If they believe in all of the above, really let it be all of the above.”

But that seems unlikely. Instead, the Trump administration is promoting gas power, though it has not taken steps to deal with the five-or-more-year waitlists to even buy gas turbines or their rapidly inflating costs. Its exotic nuclear bets won’t pay off for years, if ever.

Americans will have to look elsewhere for a remedy, and after so many pessimistic conversations, I finally found someone who was not only unfazed by recent developments but also optimistic about the future.

Pier LaFarge hails from Alabama and runs a startup called Sparkfund, which works with utilities to tap the benefits of clean and distributed energy. He speaks the language of the cleantech world but sees things differently than many in that cohort do.

We won’t crash headlong into an energy crisis, LaFarge assured me, precisely because everyone’s talking so much about crashing headlong into an energy crisis. This point recalled the Heisenberg uncertainty principle from my high school chemistry days: The act of observing something changes the thing that is observed.

Utilities and data center developers, LaFarge said, are coalescing around the understanding that demand during a relatively small number of hours in the year is constraining the AI buildout.

For decades, utilities built out the grid to meet the few hours of the year when demand peaks. That leaves capacity — in terms of power plants and transmission and distribution lines — wildly underutilized much of the time. The energy crisis won’t materialize, LaFarge argues, because it will catalyze the power sector to improve utilization of the existing grid.

Solve for a few moments of stress, and AI’s voluminous consumption of kilowatt-hours can support the fixed costs of running the grid for everyone else.

“Cheap batteries and data centers solve all of it,” he said. “You charge up when there’s excess, you drop it on the transmission and distribution corridors, you serve the data centers, downward pressure on rates, you win the future.”

In Oregon, an AI customer is already directly paying for grid batteries that will be used to benefit all of Portland General Electric’s customers. LaFarge said he has seen other confidential AI energy service agreements that will put multiple billions of dollars of downward pressure on utility rates for regular customers.

That’s more or less what Energy Secretary Chris Wright was talking about on his December publicity tour, though he attracts skepticism from clean-energy analysts when his idea for smart capacity investment amounts to forcing aging coal plants to stay open and hemorrhage money that other people have to pay for.

But if AI companies procure batteries, or portfolios of distributed energy and controllable demand, the economics change drastically. This would, in fact, achieve the cleantech sector’s long-held dream of an interactive and decentralized energy system.

This rosy scenario could fail to materialize for myriad reasons — states and regions failing to build grid infrastructure, regulators letting utilities dump billions of dollars into gas-plant construction at inflated costs instead of targeted battery investments, local leaders giving data centers sweetheart deals instead of demanding they pitch in.

But if batteries are allowed to play, the AI-fueled energy crisis could join the long list of energy crises that never came about. It’s comforting to know that’s at least a possibility.

Federal regulators are demanding that PJM Interconnection, the country’s biggest power market, find a faster way to connect data centers to the grid without spiking energy costs or threatening reliability.

Those regulators and other energy experts increasingly believe that a practice known as flexible interconnection is key to juggling those imperatives — and a recent study offers compelling supporting evidence.

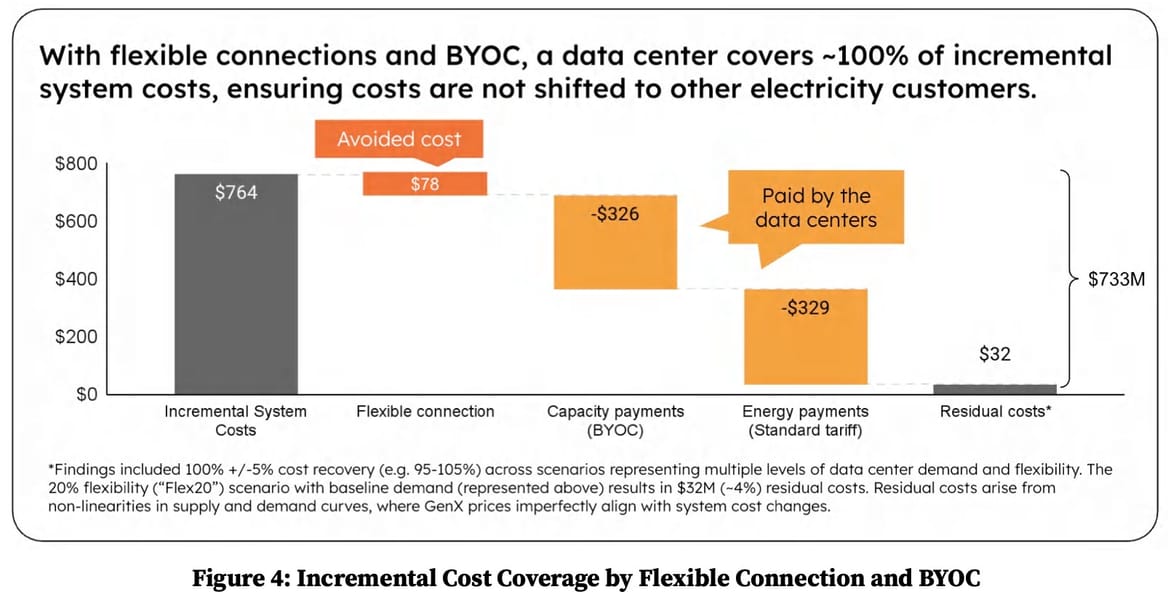

Flexible interconnection is simple in principle: Power-hungry customers like data centers supply their own power during the handful of hours per year when overstressed grids can’t handle their needs, allowing them to get online much faster and also save money for customers at large.

But to date, only a handful of utilities and grid operators have developed the technical and regulatory structures to make flexible interconnection a reality.

Astrid Atkinson, CEO of Camus Energy, and Carlo Brancucci, CEO of Encoord, whose companies aim to enable flexible interconnection, say that PJM could deploy the practice on a large scale. That argument is backed by a unique analysis of real-world conditions — modeled across every hour of the year on the same transmission grids that PJM manages — conducted by Camus, Encoord, and Princeton University’s ZERO Lab.

Their December report looks at six sites in mid-Atlantic states served by PJM. It concludes that a 500-megawatt data center using flexible interconnection and providing its own power during times of peak demand could connect three to five years faster than one that has to wait for grid upgrades and new power plants to be built in order to support its full power needs. By paying for the resources to cover any peak demand deficits, these flexible data centers would avoid passing those grid and generation costs on to customers already struggling with rising energy bills tied to data center growth, the report contends.

What’s more, the methods used in the report can be used by grid operators and utilities in PJM and across the country to enable other real-world flexible interconnection studies using standard interconnection tools and datasets, Brancucci said. “Everything else flows from that — what type of interconnection you need, what type of flexibility you need, what kind of contracts and agreements you need.”

“Our companies both offer commercial products that can do this,” said Atkinson, who co-founded Camus in 2019 after leading the team that maintains reliable computing for Google, the report’s sponsor and the preeminent tech giant working on real-world flexible interconnection projects today. In fact, she said, “we’re doing commercial modeling of similar sites right now.”

Data center flexibility is a hot topic. Recent reports from Duke University, think tank RMI, and analytics firms GridLab and Telos Energy all explore its viability and benefits.

But the report from Camus, Encoord, and ZERO Lab differs in a few ways that make it a far more practical blueprint for flexible interconnection, Atkinson said.

The first thing that distinguishes their report is that it uses in-depth, real-world data.

To approve flexible interconnections, utilities, grid operators, and data center developers must have data on power flows from generators across high-voltage transmission grid networks to giant power users. “You do need privileged data access to do this,” Atkinson said — and other research teams haven’t had that access.

But Camus, which provides grid orchestration software for utilities across the United States, including Pennsylvania’s PPL Electric Utilities and Duquesne Light Co., has that data for the six sites it modeled, Atkinson said. She wouldn’t reveal which utilities provided the data or the location of the sites, which in the report were given animal names such as Koala, Pony, Shark, and Whale. But she did confirm that they represent realistic targets for flexible interconnection.

The second thing that sets the report apart, according to Brancucci, is that it integrates the real-world operating conditions and constraints of the transmission networks serving data center sites. To do that, they used Encoord’s software platform, which simulates how real-world transmission networks operate during all 8,760 hours of the year.

“A 500-megawatt demand will have major impacts on any utility,” said Brancucci, who co-founded Encoord in 2019 after working as a senior research engineer at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Colorado and as a researcher at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre. “That will change the way power flows. And when power flow changes, you need to consider different security constraints.”

Such analyses consider not just business-as-usual conditions but also emergencies when power plants or transmission lines fail and grid operators must act quickly to prevent widespread outages. “This is the type of transmission analysis any ISO or utility is going to do when considering new load,” he said, and it’s a must-have for approving a new 500-megawatt customer.

Encoord works with transmission system operators and utilities struggling to ensure reliable service under a variety of conditions, including during winter storms when fossil gas systems fail. “If 10 utilities and 10 hyperscalers came to us and said, ‘We want to interconnect across 10 sites,’ we could redo this easily,” Brancucci said.

The results for the six sites in the December report show that transmission constraints would force four of them to curtail significant portions of their 500-megawatt peak power demand or build enough on-site generation and battery storage to cover these gaps — but only for less than 35 hours per year. The other two sites did not have transmission constraints.

The third thing that distinguishes their report is that they were able to tap into a model developed by researchers at ZERO Lab and MIT to assess how adding data centers to the grid would affect the amount of generation capacity that PJM needs to cost-effectively meet peak electricity demand.

That model enabled them to analyze how individual data centers could secure a mix of faster-to-build power sources, including solar power, wind power, and hybrid renewable-battery systems, as well as secure commitments from other customers willing to lower their power use to cover data centers’ needs through demand response or virtual power plants.

Ultimately, the new data underscores in the most definitive terms yet that flexible interconnection is viable in PJM, Atkinson said. And if PJM were to allow it, data center developers would likely be more than willing to take on the responsibility of securing their own resources to relieve those rare constraints, she added. Doing so could allow them to get online in two or three years, rather than needing to wait five to seven years for new transmission or generation.

“Data centers are willing to pay more if they can connect, in many cases, because the opportunity costs” of being forced to wait for years “far outweigh the costs of capacity,” she said. “They just need to know how much they need to build.”

And once they’re armed with that knowledge, data centers can take on the cost of securing their own resources, which would almost completely eliminate the need to build more grid infrastructure and power plants, reducing costs for all PJM customers, according to the report.

PJM isn’t the only grid operator or utility facing data center–driven cost pressures. But its challenges are more acute than most. PJM has a massive interconnection backlog that has created multiyear delays for new generation seeking to connect to its grid. And its capacity market structure is forcing up utility rates today to cover the future costs of serving forecasted data center demand.

PJM hasn’t been able to gain consensus from stakeholders — including utilities, power plant owners, big corporate energy users, and data center developers — on how to fix these problems, even as the more than 67 million customers that get power from PJM’s system face spiking utility bills to cover those costs.

That lack of consensus has prevented PJM from developing a key policy that could allow flexible interconnection to happen, Atkinson said. In order for the method laid out in the December report to work, PJM and member utilities would need to allow data centers to interconnect via something called “conditional firm” grid service.

In simple terms, this means blending traditional, “firm” service for the portion of power needs that can be supplied without grid upgrades and “conditional” service, which requires data centers to cut their power use or supply their own electricity needs during critical hours.

PJM doesn’t provide this kind of option for customers — though it may have it soon enough. In December, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ordered PJM to create structures that would allow data centers and other big customers to connect to its grid in more flexible ways. That order set out a variety of methods for PJM to pursue, including a structure called “interim non-firm transmission service,” which closely approximates the conditional firm service that Camus and Encoord envision.

“At its core, the FERC order moves PJM away from ‘full freight’ assumptions and toward studying and serving large loads based on their actual time-varying grid use,” Brancucci said. “That’s exactly the premise behind the conditional firm service model we analyzed in a few locations in PJM.”

Similar innovations are being pursued by grid operators in the Midwest and Texas, Atkinson noted. The Department of Energy has ordered FERC to launch a fast-track rulemaking to require grid operators and utilities to expedite data center interconnections.

“Today, no market really allows you to have a mix of grid power and on-site power that’s reasonably managed,” Atkinson said. But a growing number of grid experts agree that flexible interconnection is, as she put it, “the only practical way to meet these requirements.”

An enormous and novel energy storage project could soon break ground in California after receiving state approvals just before Christmas.

The startup Hydrostor’s Willow Rock project would store 500 megawatts of power that could be injected into the grid for up to eight hours, totaling 4 gigawatt-hours. That’s more gigawatt-hours than any lithium-ion battery offers, and a rare step forward for a major long-duration energy storage project. Once online, it could prove a crucial tool for California, where intermittent solar generation has become the state’s top source of electricity.

Hydrostor received permission to start building from the California Energy Commission, which signs off on environmental approvals for large thermal power plants. This has become a rarity in an era when the state pretty much exclusively builds solar and battery plants. Hydrostor, however, compresses air in underground caverns and then releases it to turn conventional turbines and send power back to the grid. Its roster of equipment put the project under the commission’s jurisdiction.

“These are the major approvals. It basically allows us to get to a shovel-ready status,” Jon Norman, president of Hydrostor, told Canary Media.

That means Hydrostor can technically begin construction on the 88.6-acre parcel it controls, where rural Kern County hits the Mojave Desert.

But Hydrostor won’t actually start building until it secures paying customers for the full planned capacity. So far, Central Coast Community Energy has contracted for 200 megawatts of Willow Rock’s capacity. Hydrostor is negotiating contracts for another 50 to 100 megawatts, which leaves 200 to 250 megawatts up for grabs.

That uncontracted capacity stands in the way of Hydrostor securing the financing it needs to pay for the roughly $1.5 billion project. Lenders or investors want assurances that the innovative installation will make enough money to pay them back, with a return. Otherwise, the project is exposed to merchant risk: Maybe Hydrostor could build it anyway, bid into the wholesale markets, and make good money. But that’s too risky a bet for most financiers, who want to see firm customer commitments.

Two factors further complicate the pitch to financiers. Because Hydrostor is trying to build a fundamentally new type of storage plant, there isn’t a clear market comparison to benchmark against. And it’s also competing in a fundamentally new type of market niche: long-duration storage.

Many analysts have predicted the physical need for longer-term grid storage as more and more of a region’s electricity comes from wind and solar power. Few regions have developed workable market structures to get ahead of that need, since today’s power markets focus on short-term optimization rather than long-term infrastructure planning.

California, though, has supplemented its power markets with a centrally driven push for long-duration storage. The state’s utility regulator required power providers to procure a collective 1 gigawatt of storage that lasts for eight or more hours. That order prompted Central Coast Community Energy to sign the deal with Hydrostor.

In September, the California Public Utilities Commission recommended a portfolio including 10 gigawatts of eight-hour storage for 2031, as part of the state’s planning for its transition to 100% clean electricity. That means a procurement order could come soon, and Hydrostor, with its permits in order, would be in position to compete for that.

“They’ve identified the need for very near-term procurement, so we’re looking forward to participating in that,” Norman said. “We also know that we’re very competitive.”

He also said it’s “very likely” that Hydrostor breaks ground this year.

That would kick off an estimated four-to-five-year construction timeline, Norman said. The company has created a “pretty sophisticated Joshua tree management plan” to protect the alien-looking vegetation unique to the Mojave, where it will build the project. It also secured a water supply and place to deposit the rock it carves from the earth, and it is currently finalizing an engineering, procurement, and construction contractor, Norman said.

That timeline should put Willow Rock in a good place to help California meet those medium-term storage needs. Given current trends, in five or so years the state will be even more awash in surplus solar generation at midday, and in even greater need of on-demand energy to keep the lights on after the sun sets.

In other words, if the regulator’s numbers are right, California will need many more Willow Rocks to keep up, so it’s about time one of them got going.

Those in the energy sector, like everyone else, could not stop talking about artificial intelligence this year. It seemed as if every week brought a new, higher forecast of just how much electricity the data centers that run AI models will need. Amid the deluge of discussion, an urgent question arose again and again: How can we prevent the computing boom from hurting consumers and the planet?

We’re not bidding 2025 farewell with a concrete answer, but we’re certainly closer to one than we were when the year started.

To catch you up: Tech giants are constructing a fleet of energy-gobbling data centers in a bid to expand AI and other computing tools. The build-out is encouraging U.S. utilities to invest beaucoup bucks in fossil-fueled power plants and has already raised household electricity bills in some regions. Complicating things further is that many of today’s proposed data centers may never get built, which would leave the rest of us to foot the bill for expensive and unnecessary power plants that bake the planet.

It’s all hands on deck to find solutions. Lawmakers across every state considered a total of 238 bills related to data centers in 2025 — and a whopping half of that legislation was dedicated to addressing energy concerns, according to government relations firm MultiState.

Meanwhile, the people who operate and regulate our electric grid worked on rules to get data centers online fast without breaking the system. One idea in particular gained traction: Let the facilities connect only if they agree to pull less power from the grid during times of über-high demand. That could entail literally computing less, or outfitting data centers with on-site generators or batteries that kick in during these moments.

Even the Trump administration got in on the action, with Energy Secretary Chris Wright directing federal regulators in October to come up with rules that would let data centers connect to the grid sooner if they agree to be flexible in their power use. But this idea of “load flexibility” is still largely untested and has its skeptics, who argue that it’s technically unrealistic under current energy-market frameworks.

And then there are the hyperscalers themselves. Big tech companies with ambitious climate goals are signing power purchase agreements left and right for energy sources from geothermal to nuclear to hydropower. Google unveiled deals with two utilities this summer to dial down data centers’ power use during high demand. Texas-based developer Aligned Data Centers announced this fall that it would pay for a big battery alongside a computing facility it’s building in the Pacific Northwest, allowing the servers to get up and running way faster than if the company waited for traditional utility upgrades.

Expect more action on this front in 2026. Local opposition to data centers is on the rise, power-demand projections are still climbing, and speculation is mounting that the entire AI sector fueling those forecasts is a big old bubble about to pop.

Since spring of last year, North Carolina’s largest utility has been testing whether household batteries can help the electric grid in times of need — and now the company wants to roll out the plan to businesses, local governments, and nonprofits, too.

Duke Energy has already paid hundreds of North Carolinians to let it tap power from their home storage systems when electricity demand is highest. It’s Duke’s first foray into running a “virtual power plant,” in which the company manages electricity produced and stored by consumers, much as it would control generation from its own facilities.

In September, the utility proposed a similar model for its nonresidential customers, asserting that the scheme will save money by shrinking the need for new power plants and expensive upgrades to the grid. The recognition signals a way forward for distributed renewable energy and storage as state and national politicians back away from the clean energy transition.

The initiative now needs approval from the five-member North Carolina Utilities Commission, where the virtual-power-plant model has faced some skepticism. But the apparent merits of Duke’s plan, which has broad backing, may be too enticing for commissioners to ignore — especially when the state is grappling with rising rates and voracious demand from data centers and other heavy electricity users.

“In an era of massive load growth, something that should lower costs to customers while helping meet peak demand — to me, it’s an absolute no-brainer,” said Ethan Blumenthal, regulatory counsel for the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, an advocacy group. “I’m hopeful that [regulators] see it the same way.”

Duke’s trial residential battery incentives grew out of a compromise with rooftop solar installers. Like many investor-owned utilities around the country, the company sought to lower bill credits for the electrons that solar owners add to the grid. When the solar industry and clean energy advocates fought back, the scheme dubbed PowerPair was born.

The test program provides rebates of up to $9,000 for a battery paired with rooftop photovoltaic panels. It’s capped at roughly 6,000 participants, or however many it takes to reach a limit of 60 megawatts of solar. Half of the households agree to let Duke access their batteries 30 to 36 times each year, earning an extra $37 per month on average; the other half enroll in electric rates that discourage use when demand peaks.

The incentives have been crucial for rooftop solar installers, who’ve faced a torrent of policy and macroeconomic headwinds this year, and they’ve proved vital for customers who couldn’t otherwise afford the up-front costs of installing cheap, clean energy.

But the PowerPair enrollees already make up 30 megawatts in one of Duke’s two North Carolina utility territories and could hit their limit in the central part of the state early next year, leaving both consumers and the rooftop solar industry anxious about what’s next.

Duke’s latest proposal for nonresidential customers — which, unlike the PowerPair test, would be permanent — is one answer.

The proposed program is similar to PowerPair in that it’s born of compromise: Last summer, the state-sanctioned customer advocate, clean energy companies, and others agreed to drop their objections to Duke’s carbon-reduction plan under several conditions, including that the utility develop incentives for battery storage for commercial and industrial customers. The Utilities Commission later blessed the deal.

“This was pursuant to the settlement in last year’s carbon plan,” said Blumenthal, “so it’s been a long time coming.”

While many industry and nonprofit insiders refer to the scheme as “Commercial PowerPair,” its official title is the Non-Residential Storage Demand Response Program.

That name reflects the incentives’ focus on storage, with solar as only a minor factor: Duke wants to offer businesses, local governments, and nonprofits $120 per kilowatt of battery capacity installed on its own and just $30 more if it’s paired with photovoltaics.

The maximum up-front inducement of $150 per storage kilowatt is much less than the $360 per kilowatt offered under PowerPair. But more significant for nonresidential customers could be monthly bill credits: about $250 for a 100-kilowatt battery that could be tapped 36 times a year, plus extra if the battery is actually discharged.

Unlike households participating in PowerPair, which must install solar and storage at the same time to get rebates, nonresidential customers can also get the incentives for adding a battery to pair with existing solar arrays.

“That could be very important for municipalities around North Carolina that have already installed a very significant amount of solar, but very little of that is paired with battery storage,” said Blumenthal.

Duke has high hopes for the program, projecting some 500 customers to enroll. Five years in, the resulting 26 megawatts of battery storage would help it avoid building nearly 28 megawatts of new power plants to meet peak demand, saving over $13.6 million. That’s significantly more than the cost of providing and administering the incentives, which Duke places at nearly $11.8 million.

“The Program provides a source of cost-effective capacity that the Company’s system operators can use at their discretion in situations to deliver economic benefits for all customers,” Duke said in its September filing to regulators. “Importantly, the Company received positive feedback from its customers … when sharing the details of the Program.”

Indeed, the proposal has been met with support not just from the Sustainable Energy Association and other clean energy groups but also organizations like the North Carolina Justice Center, which advocates for low-income households. It earned praise from local governments represented by the Southeast Sustainability Directors Network and conditional support from the state-sanctioned customer advocate, known as Public Staff, too.

The good vibes continued last week, when Duke responded positively to detailed suggestions from these parties on how to improve the program. That included a request from Public Staff that the company raise the per-customer limit on battery capacity to align with the maximum amount of solar that a business or other nonresidential consumer can connect to the grid, which is currently 5 megawatts.

“Larger batteries sited at larger customer sites can help provide more significant system benefits and can reduce the need for incremental utility-owned energy storage installed at all ratepayers’ expense,” the agency told regulators in its November comments. It recommends a cap tied to a customer’s peak demand; for example, a business that consumes more energy at once should get incentives for a bigger battery. Duke agreed in its Dec. 5 comments, calling that limit “reasonable.”

Still, questions remain about how to make the incentives most impactful.

Public Staff, for instance, believes Duke should increase its monthly payment to customers for keeping their batteries charged and ready to deploy. This “capacity credit” is now set at $3.50 per kilowatt but effectively reduced to $2.48, because the utility assumes that a percentage of users won’t properly maintain their systems, based on its experience with households. The company calls that a “capability factor,” but the agency dubs it “collective punishment” for all customers and says it should be eliminated or recalibrated for “more sophisticated” nonresidential participants.

Raleigh, North Carolina–based 8MSolar, a member of the Sustainable Energy Association, is among the many installers that have been eagerly anticipating Duke’s proposal.

The program on its own likely won’t “move the needle unless the incentives get bumped up,” said Bryce Bruncati, the company’s director of sales. However, the scheme could tip the scales for large customers when stacked on top of two federal tax opportunities: a 30% incentive available through the end of 2027 and a deduction tied to the depreciation value of the system — up to 100% thanks to the Republican budget law passed this summer.

“The combined three could really have a big impact for small- to medium-sized commercial projects,” Bruncati said. The Duke program would represent “a little bit of icing on the cake.”

Whatever their size and design, the fate of the incentives rests entirely with the Utilities Commission, now that the final round of comments from Duke and other stakeholders is in. There’s no timeline for a decision.

At least one commissioner, Tommy Tucker, has voiced skepticism about leveraging customer-owned equipment to serve the grid at large. “I’m not a big fan of the [demand-side management] or virtual power plants because you’re dependent upon somebody else,” the former Republican state senator said at a recent hearing, albeit one not connected to the Duke program.

Still, Blumenthal waxes optimistic. After all, Tucker and three other current members of the commission are among those who ruled last year that Duke should present the new incentive program.

“They seem to recognize there is value to distributed batteries being added to the grid,” Blumenthal said. “The fact that [the proposal] is cost-effective is key because the idea is, the more of it you do, the more savings there are.”

Two corrections were made on Dec. 10, 2025: This story originally misstated the number of times a year that Duke can tap a PowerPair participant’s battery; it is 30 to 36 times a year, not 18. The story also originally misstated the enrollment Duke expects for the nonresidential program; the utility expects 26 megawatts of batteries, not 26,000 customer participants.