Geothermal energy was spared in President Donald Trump’s sweeping tax and spending law, which made deep cuts to incentives for other forms of clean energy. But developers of the resurgent energy source may still face difficulties ahead due to complex stipulations folded into the new law, among other Trump administration policies.

The “big, beautiful” Republican legislation largely preserves investment and production tax credits for geothermal power plants — as well as battery storage, nuclear, and hydropower projects — established by the Inflation Reduction Act. Incentives for wind and solar, however, are sharply curtailed, and subsidies for residential clean energy projects will abruptly end after this year.

Geothermal advocates celebrated the outcome for their industry, which they say will be vital to scaling the resource in the United States to meet the nation’s soaring power demand. The sector has attracted a lot of attention in recent years because it can provide carbon-free power around the clock — something solar and wind can’t do — and technological advances are making it possible to deploy geothermal in places that conventional plants can’t go.

This “policy milestone highlights the geothermal industry’s role in fortifying grid resilience and national security,” Vanessa Robertson, director of policy and education for Geothermal Rising, an industry association, said in a statement. “With certainty in place, we look forward to seeing projects advance and innovative partnerships flourish.”

Still, the industry isn’t immune to the broader market challenges created by Trump’s policies, despite its more favorable treatment from Congress.

New tariffs on things like steel and aluminum have increased the cost of drilling equipment, heat exchangers, and other key components. A provision in the budget bill aimed at restricting Chinese companies and individuals from accessing tax credits will make it harder for developers to prove compliance, increasing the risk for investors who finance clean energy projects.

“We’re making an ugly layered cake of barriers to quick and clean project development,” said Advait Arun, a senior associate for energy finance at the Center for Public Enterprise, a nonprofit think tank.

Geothermal plants, which harness Earth’s heat to generate power, have for decades represented less than 1% of the U.S. electricity mix. That’s because conventional plants tend to be viable only when located near natural formations like hot springs, where the heat is easier to reach, but which only occur in a handful of places in the United States.

New tools and techniques are emerging that make it possible to put geothermal plants in more parts of the country.

The startup Fervo Energy completed America’s first “enhanced geothermal system” in late 2023 — a 3.5-megawatt pilot plant in Nevada backed by Google. Now, the Houston-based company is building the world’s first large-scale enhanced geothermal plant in Utah’s high desert. Fervo has raised hundreds of millions of dollars in capital to drill dozens of wells for the 500-megawatt Cape Station, with the first 100 MW slated to start delivering power to the grid in 2026.

In June, the startup XGS Energy announced plans to build a 150-MW next-generation geothermal project in New Mexico by 2030 to support Meta’s data center operations. Meta, which owns Facebook and WhatsApp, signed a similar agreement last year with Sage Geosystems to build 150 MW of geothermal power at an unspecified site east of the Rocky Mountains. The first phase of that project is set to come online in 2027.

Geothermal has long drawn bipartisan support and has so far dodged Trump’s broader attacks on renewable energy. It helps that the new geothermal wave has considerable overlap with the oil and gas industry, sharing the same drilling equipment, workforce, and investors. U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright, previously the CEO of a fracking company that invested in Fervo, played an active role during budget negotiations to shield geothermal from sweeping cuts to Inflation Reduction Act incentives.

Under the new law, geothermal and other baseload clean power sources can qualify for the full 48E investment tax credit or the 45Y production tax credit if they begin construction by 2033, after which point the credits will gradually decrease to zero in 2036. The concrete phase-out schedule differs from the IRA, which allowed more flexibility and could’ve kept the incentives in place for several more years, according to Geothermal Rising.

Wind and solar facilities, meanwhile, must either start operating before the end of 2027 or begin construction by next summer to obtain credits. Geothermal heat pumps, which heat and cool buildings, will lose access to residential tax credits after 2025.

For next-generation geothermal firms, the tax incentives are crucial to getting the first slate of projects up and running. Developers use the promise of future tax credits as collateral to raise the many millions in financing they need to explore suitable project sites and deploy novel drilling technologies. The credits also help to attract major customers, including tech giants that are looking for a variety of baseload power sources to run their sprawling data centers.

“They help the market to develop,” said Mehdi Yusifov, the director of data centers and AI at Project InnerSpace, a geothermal advocacy group. “Tax credits of this kind can … help get infrastructure built on a mega scale.”

Yusifov and Nico Enriquez, a principal at Future Ventures, studied the potential cost of serving a “hyperscale” data center with power from a 1-gigawatt enhanced geothermal project in a place like the Western U.S. In a new analysis, they found this novel project could achieve a levelized cost of energy of $119 per megawatt-hour without the investment tax credit — significantly better than estimated costs for nuclear power. With the tax credit, the hypothetical geothermal system could achieve $88 per megawatt-hour, which is competitive with the upper range for a fossil-gas power plant.

“It seems like there’s a dam that would break if it could be proven that [geothermal] can produce power anywhere in the range below Three Mile Island,” said Enriquez, referring to the shuttered nuclear plant in Pennsylvania that is expected to restart to serve Microsoft’s growing energy appetite.

“That’s another reason why this investment tax credit is so important, because it makes it possible to have the dam break,” he added. “And suddenly you can flood the market with these projects that are giving us critical infrastructure.”

It’s unclear whether the budget bill will undermine some next-generation projects due to the anti-China provisions attached to these key incentives. The rules, known as “foreign entity of concern” restrictions, will require companies to scrutinize their supply chains to an unprecedented degree, with potentially onerous and costly legal implications that make it harder for projects to claim incentives.

“It remains to be seen how developers of these really innovative technologies can navigate this, because it’s not going to be the easiest process from here on out,” said Arun of the Center for Public Enterprise.

Even as the headwinds swirl, geothermal developers continue to make significant strides to improve their technologies. Both Fervo and the federal Utah Forge initiative have said they’ve dramatically increased drilling speeds and efficiencies in just a handful of years, with Fervo reducing its per-well costs by millions of dollars. For startups, access to tax incentives allows them to get to work to make such advances in the field, Enriquez said.

“There’s an amount we save long-term if we invest upfront in these tax credits, because of the learning curve,” he said. “If we can maintain [the momentum] for the next five years, I think this industry will be one of the key power sources for the U.S.”

The megabill passed by Republicans in Congress and signed into law by President Donald Trump last week creates many challenges for clean energy — enough to choke off lots of new solar and wind power projects, and cast uncertainty over everything from battery storage deployments to EV factories.

The only saving grace is that it could have been much worse.

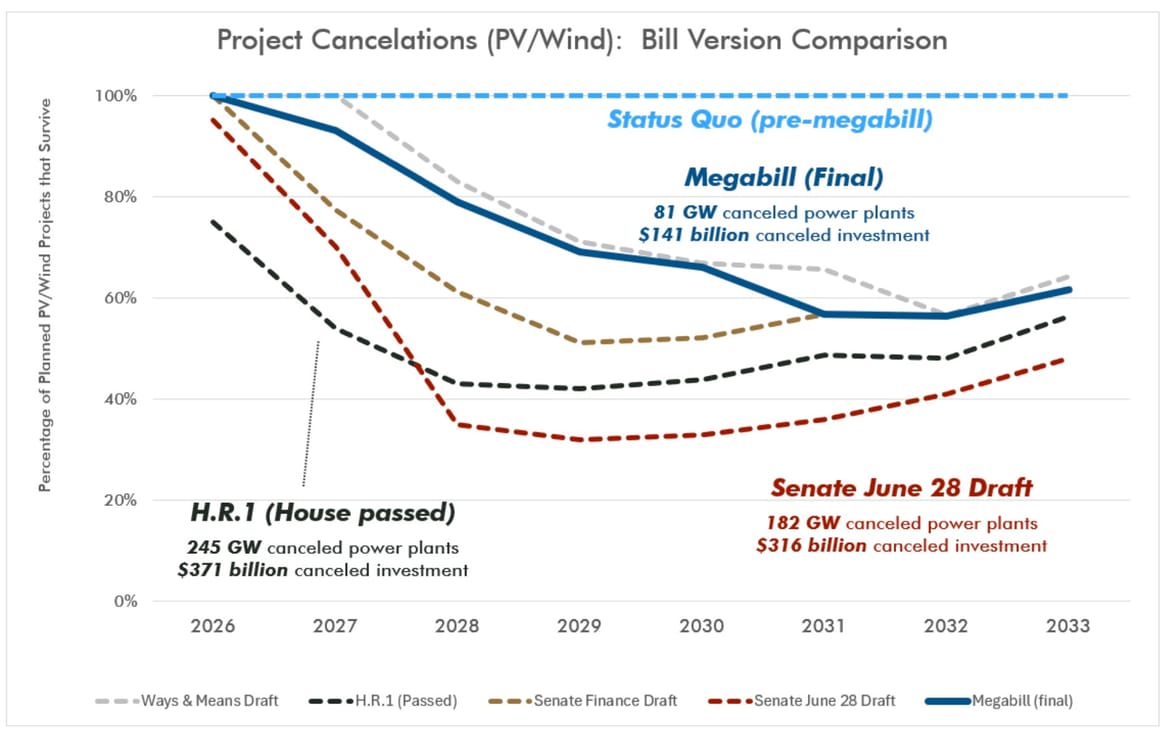

The new law could reduce investment in solar and wind projects by about $141 billion and kill 81 gigawatts of potential new generation capacity through 2033 compared to what would have happened if it didn’t pass, according to estimates from solar and battery project investor Segue Sustainable Infrastructure.

But previous versions of the bill from House Republicans, and a draft unveiled by Senate Republicans on June 28, would have spelled the demise of more than twice as much clean power and domestic investment, according to Segue’s previous analyses.

What changed? A handful of Senate Republicans, pressed by clean energy advocates, amended the bill in the industry’s favor, averting “a complete catastrophe,” according to David Riester, founder and managing partner of Segue, which is involved in about 120 solar and battery projects across the country.

Nevertheless, the law still rapidly phases out tax credits for solar and wind.

Under the Inflation Reduction Act, projects that started construction before 2033 were assured tax credits that they could use or sell to reduce the cost of building, and thus, the price of the power they offer to long-term offtakers, like utilities or corporations. Although the new law largely preserves that timeline for geothermal, nuclear, hydropower, and battery storage development, it dramatically tightens the deadlines for wind and solar projects, requiring them to either be operating by the end of 2027 or start construction by next summer to access incentives.

Developers and financiers like Segue now have 12 months to decide whether they believe a given wind or solar installation can hit the milestones required to access crucial tax credits.

If they don’t think it can, they’ll pull out of the project. That could mean a lot of abandoned plans for Segue, whose portfolio is mostly made up of earlier-stage developments.

“We often pose the question to each other: ‘If we lean into this, are we investing, or are we gambling?’’’ Riester said. “There are some project profiles for which the answer will almost certainly be ‘gambling’ a year from now, and we will kill those.”

Segue isn’t alone. Financiers and developers across the country are grappling with this as they consider whether to move forward with much of the hundreds of gigawatts of solar, battery, and wind projects being planned around the country.

“When you rip the rug out suddenly, it creates a moment where the owners of all these projects, in their various stages of development, have to face the fact that they don’t know exactly what their revenue line is going to look like,” Riester said.

Developers ultimately have little control over when a project can connect to the grid and start delivering power. That’s why the most vital change in the final version of the bill is one pushed by Sens. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa), Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), and Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), which gives wind and solar projects until July 4, 2026, to start construction to secure tax credit eligibility.

Projects that meet this deadline will be eligible as long as they’re completed and placed in service within four years of start of construction. Previous versions of the bill would have given those projects only 60 days to commence construction, and then required them to be placed into service by 2028 to win credits.

But project developers called the “placed in service” deadline tantamount to an immediate tax-credit cutoff, given the impossibility of being able to assure investors that they’d be able to get online in time. Already, grid bottlenecks force projects to wait an average of five years to secure interconnection.

The “commence construction” status is the traditional hinge point for tax credit eligibility. It’s far more within a developer’s control than placing a project into service, and can be verified using established methods like the “5% safe-harbor test,” which involves incurring 5% or more of the total cost of the facility in the year construction begins.

With 12 months to reach this construction milestone, project developers have “a bit more time to see how projects’ existing development risks evolve before the ‘Do I safe harbor this project?’ question requires an answer and action,” Riester said.

There is a cloud hanging over relying on safe harbor provisions, however, noted Andy Moon, CEO and cofounder of Reunion Infrastructure, a company working in the multibillion-dollar market for clean-energy tax credit transfers. President Trump issued an executive order on Monday directing the Treasury Department to issue guidance restricting the use of “broad safe harbors unless a substantial portion of a subject facility has been built.”

That’s a “significant departure” from what project developers were planning for, Moon said. “Developers are scrambling to figure out how the Treasury might modify safe harbor rules.”

Not all of the wind and solar farms that could get started in the next 12 months will be able to, said Jim Spencer, president and CEO of Exus Renewables North America, a company that owns and builds clean energy.

The new mid-2026 deadline will launch a rush to secure all the equipment that projects require. Some developers will inevitably be crowded out, unable to buy what they need in time.

“We’re a well-capitalized developer with the ability to buy equipment in advance,” Spencer said, but not all firms are in the same position. “A lot of the less well-capitalized developers may have good projects. But if they can’t grandfather those projects, either by starting construction or by procuring equipment, there’s not much of a value proposition there.”

That looming deadline also presages a big drop in new solar and wind projects later this decade, once the last ones eligible for tax credits are built.

“You’ll have a rush of safe-harboring” before the 12-month period expires, Moon said. “But greenfield development is going to freeze after that until the market adjusts.”

That’s because energy buyers won’t immediately want to accept the higher prices set by developers who lack the financial boost of tax credits. “There’s going to be a price-discovery phase, when project developers all of a sudden are missing capital for 30% to 40% to 50% of their project costs,” he said. “Electricity prices are going to have to rise significantly to make up the shortfall.”

Wholesale electricity prices could increase 25% by 2030 and 74% by 2035 due to the loss of low-cost renewable energy and a rise in the cost of fossil gas to fuel the power plants that will need to make up the difference, according to modeling of the law from think tank Energy Innovation.

The process of price discovery will lead to what Riester described as a “price correction” — energy buyers coming to terms with how much more expensive electricity will become and making deals accordingly. But that will take some time.

In the meantime, there will be a gap in the deployment of clean energy — by far the biggest source of new power on the U.S. grid. That gap will have consequences as power demand is climbing nationwide.

Slower power-plant growth will significantly disrupt the electricity needs of factories, data centers, big-box stores, and “everything that we want to bring back onshore” that are “teed to these power projects,” Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), one of three Senate Republicans who voted against the bill, said in a speech on the chamber’s floor in late June. The disruptions will cause “a blip in power service, because there isn’t going to be a gas-fired generator anytime soon.”

Developers face wait times of five to seven years for new gas turbines. Nuclear and geothermal power plants take even longer to build.

Eventually, the market will find a new equilibrium. If solar, wind, and batteries are the only power sources that can be built quickly in the near term, utilities and corporate customers will figure out a price they’re willing to pay.

“But on the way to that steady state, there will be a lot of rockiness in the market,” Riester said. During that time, Segue and many other energy-market observers predict a significant shortfall in new power supply to meet demand.

“There will still be tons of projects in that 2028 to 2031 window that get killed because visibility into economic viability fails to arrive before development expenses become uncomfortably high,” Riester said. “That’s where the capacity shortage is likely to peak” — when Trump’s presidency will be over.

As temperatures across New England soared above 100 degrees Fahrenheit in recent weeks, solar panels and batteries helped keep air conditioners running while reducing fossil-fuel generation and likely saving consumers more than $20 million.

“Local solar, energy efficiency, and other clean energy resources helped make the power grid more reliable and more affordable for consumers,” said Jamie Dickerson, senior director of clean energy and climate programs at the Acadia Center, a regional nonprofit that analyzed clean energy’s financial benefits during the recent heat wave.

On June 24, as temperatures in the Northeast hit their highest levels so far this year, demand on the New England grid approached maximum capacity, climbing even higher than forecast. Then, unexpected outages at power plants reduced available generation by more than 1 gigawatt. As pressure increased, grid operator ISO New England made sure the power kept flowing by reducing exports to other regions, arranging for imports from neighboring areas, and tapping into reserve resources.

At the same time, rooftop and other “behind-the-meter” solar panels throughout the region, plus Vermont’s network of thousands of batteries, supplied several gigawatts of needed power, reducing demand on an already-strained system and saving customers millions of dollars. It was a demonstration, supporters say, of the way clean energy and battery storage can make the grid less carbon-intensive and more resilient, adaptable, and affordable as climate change drives increased extreme weather events.

“As we see more extremes, the region still will need to pursue an even more robust and diverse fleet of clean energy resources,” Dickerson said. “The power grid was not built for climate change.”

On June 24, behind-the-meter solar made up as much as 22% of the power being used in New England at any given time, according to the Acadia Center. At 3:40 p.m., total demand peaked at 28.5 GW, of which 4.4 GW was met by solar installed by homeowners, businesses, and other institutions.

As wholesale power prices surpassed $1,000 per megawatt-hour, this avoided consumption from the grid saved consumers at least $8.2 million, according to the Acadia Center.

This estimate, however, is conservative, Dickerson said. He and his colleagues also did a more rigorous analysis accounting for the fact that solar suppresses wholesale energy prices by reducing overall demand on the system. By these calculations, the true savings for consumers actually topped $19 million, and even that seems low, Dickerson said.

In Vermont, the state’s largest utility also relieved some of the pressure on the grid by deploying its widespread network of residential and EV batteries. That could save its customers some $3 million by eliminating the utility’s need to buy expensive power from the grid and reducing fees tied to peak demand.

“Green Mountain Power has proven that by making these upfront investments in batteries, you can save ratepayers money,” said Peter Sterling, executive director of trade association Renewable Energy Vermont. “It’s something I think is replicable by other utilities in the country.”

Green Mountain Power’s system of thousands of batteries is what is often called a “virtual power plant” — a collection of geographically distributed resources like residential batteries, electric vehicles, solar panels, and wind turbines that can work together to supply power to the grid and or reduce demand. In Vermont, Green Mountain Power’s virtual power plant is its largest dispatchable resource, spokesperson Kristin Carlson said. The 72-MW system includes batteries from 5,000 customers, electric school bus batteries, and a mobile, utility-scale battery on wheels.

The network began in 2015 with the construction of a 3.4-megawatt-hour storage facility at a solar field in Rutland, Vermont. Two years later, the utility launched a modest pilot program offering Tesla’s Powerwall batteries to 20 customers, followed in 2018 by a pilot that paid customers to share their battery capacity during high-demand times. In 2022, a partnership with South Burlington’s school district linked electric school buses to the system, and in 2023, state regulators lifted an annual cap on new enrollments it had imposed on a Green Mountain Power program that leases batteries to households. The number of customers with home batteries has since grown by 72%.

“We’ve had a really dramatic expansion,” Carlson said. “It is growing by leaps and bounds.”

The network saved consumers money during the heat wave by avoiding the need to buy power at the high prices the market reached that day, but also by helping to lower the “capacity fees” charged by ISO New England. These charges are determined by the one hour of highest demand on the grid all year, and then allocated to each utility based on their contributions to that peak. By pulling power from batteries rather than just the grid, Green Mountain Power lowered its part of the peak.

If the afternoon of June 24 remains the time of peak demand for 2025, Green Mountain Power’s 275,000 customers will save about $3 million in total and avoided power purchases, the utility calculated. Looking ahead, more hot weather and further expansion of the utility’s virtual power plant will likely continue to put money back in customers’ pockets, Sterling said: “When you play that out over many years, that’s real savings to ratepayers.”

President Donald Trump’s new “big, beautiful” law repeals many — but not all — of the U.S.‘s clean-energy tax credits. The incentives that remain, though, could still prove prohibitively complex, rendering them effectively useless for energy project developers and manufacturers.

That’s because of a provision in the bill aimed at restricting Chinese companies and individuals from benefiting from those tax credits. These restrictions on “foreign entities of concern” — “FEOC” for short — combine harsh penalties with very little guidance on compliance. The impact of rules meant to limit U.S. funds flowing to China could, ironically, be to undermine U.S. efforts to compete with China, which dominates many of the industries that will bear the brunt of the requirements, experts say.

The ramifications of FEOC rules will be felt most by developers of grid-scale battery, geothermal, and nuclear energy projects as well as by companies that produce batteries, solar panels, and critical minerals in the United States. The law preserved tax credits for these sectors until the 2030s, subject to FEOC provisions.

The FEOC provisions in the bill passed last week aren’t as strict as those that emerged from a House version of the bill in May, experts say. But they’re still complex enough that experts fear it will take the U.S. Treasury Department a long time to finalize its rules for compliance. The bill sets a deadline for the department to issue its FEOC rules by the end of 2026.

During the Biden administration, the department took a year and a half to craft rules for a much narrower set of FEOC restrictions for electric vehicle batteries under the Inflation Reduction Act. It’s unlikely the agency — understaffed and overworked following cuts from the Trump administration — will be able to finalize rules for these much broader restrictions in a timely fashion, said Ted Lee, a former Biden administration Treasury official who worked on those EV tax credits.

That puts the industry in a bind. Until the guidance is finished, it will be risky for companies to claim tax credits — and riskier yet for the investors who finance clean-energy projects and factories by purchasing these credits to offset their own tax bills. These entities would face the risk of eventually having their tax credits clawed back if they’re later found to be in violation of the as-yet-unwritten rules, Lee said, among other penalties.

“When I talk to developers, manufacturers, lawyers, and tax insurers and other participants in this market, they’re not sure how they’re going to deal with this,” Lee said. “There’s a risk that some projects get so burdened in compliance and red tape that projects and investments that should move forward will not be able to.”

To make matters more challenging, the IRS has a long time to challenge tax credit claims, said Andy Moon, CEO and cofounder of Reunion Infrastructure, a company that offers software and services to support the multibillion-dollar market for tax-credit transfers. The department has six years after a return is filed, and can assess a 20% penalty for incorrect claims — in addition to clawing back the value of the credit.

The confusion ultimately threatens to put hundreds of billions of dollars worth of planned investment in clean-energy projects and factories on ice while companies wait for the details to take shape. It could also sow chaos for the hundreds of billions of dollars worth of existing projects that have been built with the assumption that they could access Inflation Reduction Act tax incentives.

It’s unclear whether every company will be able to find alternative suppliers that comply with the FEOC rules. China makes most of the world’s solar and lithium-ion battery materials and components, including those used in domestic installations and factories. For some projects, that might be OK. Certain energy developments and factories will still make economic sense without tax credits. But plenty won’t.

“The industry has not yet fully absorbed the potential impact of FEOC rules, which will kick in starting in 2026,” said Moon. “And I think that some market participants are looking at it and raising the alarm bells.”

In particular, the “material assistance” rules that go into effect next year will prove a challenge for firms, Moon said. Under those rules, factories and energy projects seeking to claim tax credits must have an increasing proportion of materials coming from companies and sources that aren’t linked to FEOC.

For manufacturers seeking credits under the Inflation Reduction Act’s 45X program, those proportions will rise from 60% in 2026 to 85% in 2030 for lithium-ion batteries, while the proportions for solar manufacturers will rise from 50% to 85% over the same time period, for example. Manufacturers of other products have their own ratios, as do wind, solar, battery, geothermal, and nuclear power projects.

It won’t be easy for companies to prove they’ve met those thresholds, Lee said. “To do that, you have to go through a calculation that’s described at a high level in the text” of the bill, he said. “But the details of how you do that calculation are somewhat unclear,” with only passing reference to existing domestic-content “safe harbor” guidance for solar, wind, and battery projects.

Yogin Kothari, chief strategy officer for Solar Energy Manufacturers for America, a coalition of U.S. solar-equipment makers, said that the companies in his organization are working with the Trump administration and members of Congress to forward “a set of rules that supports domestic manufacturers and drives demand for domestic manufacturing. Anything that undermines that will have a negative impact on these manufacturing communities.”

GOP lawmakers have good reason to develop workable rules: The vast majority of manufacturing investment generated by the Inflation Reduction Act is flowing to Republican congressional districts.

Spencer Pederson, senior vice president of public affairs for the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) trade group, highlighted the work that the organization and its member companies have taken to comply with existing “Build America, Buy America” rules set by the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Those kinds of efforts could help companies prepare to comply with the FEOC rules set to emerge from the Treasury Department, he said.

“NEMA is going to work with Treasury as best as possible to ensure that the guidance is clear and consistent and produced in a timely enough manner for companies to use the credit for those that wish to take advantage of it,” he said. Even so, “there’s going to be a decision for a number of companies and organizations as to whether or not the juice is worth the squeeze.”

But some sectors don’t have an existing framework to look to. Such guidance doesn’t exist for geothermal and nuclear power projects, or for inverters and other grid equipment, noted Advait Arun, senior associate for energy finance at the Center for Public Enterprise, a nonprofit think tank. Until the Treasury Department releases guidance on those technologies, “it’s going to be tough, if not impossible” for developers of those projects to know how to calculate their exposure to FEOC, he said.

Even if Treasury guidance does eventually offer some clarity, companies are almost certainly going to struggle to obtain the depth of information the FEOC rules in the bill appear to require. Companies tend to be secretive about their exact suppliers, Lee said, adding that this difficulty was part of what slowed down the Biden administration’s rulemaking around domestic content requirements.

“Even if you know what you’re trying to calculate, actually getting that information from your suppliers — and in many cases your suppliers’ suppliers,” as the FEOC rules require, Lee said, “is going to be extremely difficult.”

Ultimately, the extent to which this complexity slows down growth in clean energy and manufacturing construction will depend on the Treasury’s guidance, which could take years to be issued.

“I don’t know yet how hard [compliance] is going to be,” said Harry Godfrey, head of federal affairs for trade organization Advanced Energy United. “It depends on where the administration engages in additional guidance, and if it’s helpful — which we hope it would be — or if it is disruptive.”

Even before those “material assistance” restrictions begin next year, companies will need to prove they aren’t what the FEOC rules define as “specified foreign entities” or “foreign-influenced entities” to ensure they are eligible to receive tax credits.

“Those rules come into effect regardless of when you start construction,” Lee said.

These restrictions could embroil many factories and projects already built or under construction. More than 100 existing or planned U.S. solar or battery factories are owned by Chinese parent companies or backed by majority-Chinese shareholders, according to BloombergNEF analysis obtained by Heatmap.

Other companies “might not actually be owned or influenced by Chinese companies, but maybe they haven’t done all the many tests now required to prove that,” Lee said. “There’s going to be this immediate compliance hit, even for projects that have begun production or [are] about to get turned on.”

Companies under majority-Chinese ownership, such as Japan-based lithium-ion battery manufacturer AESC, have already frozen hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of U.S. factory plans. House Republicans have previously attacked other projects that license Chinese technology, such as Ford Motor Co.’s battery plant in Michigan that uses technology from China-based battery giant Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL).

“Effective control” provisions that direct the Treasury to write guidance that could bar tax credits to projects or factories that have made contract or licensing payments to specified foreign entities are particularly problematic, Lee said. “There’s an extremely broad category of things that could be caught up in that, particularly in the battery space.”

Overshadowing all these uncertainties is the fear that the Trump administration will not engage in the same good-faith approach that the Biden administration took to work with U.S. companies in their efforts to comply with FEOC rules.

Already, reports have surfaced of a deal struck between members of the ultraconservative House Freedom Caucus and Trump, who reportedly has agreed to impose administrative burdens and aggressive interpretations of agency rules to prevent solar and wind projects from being able to use the tax credits that remain available to them over the next two years.

On Monday evening, Trump issued an executive order calling on the Treasury to “take prompt action” within 45 days of the One Big, Beautiful Bill’s enactment to implement the law’s FEOC restrictions. “Reliance on so-called ‘green’ subsidies threatens national security by making the United States dependent on supply chains controlled by foreign adversaries,” the order says.

Under the new law, Republicans in Congress could choose to launch investigations into companies and refer their claims to the IRS.

“Historically IRS enforcement has been independent from the political appointees in the executive branch,” Lee said. “The norms and laws that provide that protection are being eroded by this administration. As a result, it’s quite concerning to think about what actions the Trump administration might put pressure on the IRS to take, and what enforcement priorities this administration would have.”

Lee noted that tax-credit financing structures have always had to deal with the risks that credits might be challenged by the IRS, with insurance products and careful lawyering by counterparties in tax-equity and tax-credit transfer deals. But the One Big, Beautiful Bill Act introduces a deeper level of risk than ever before.

“There will be some kind of framework for risk-mitigation strategies that will arise to handle these issues,” Lee said. “The question is, how quickly will that happen — and how much risk will the market be willing to take on?”

An update was made on July 8, 2025: This story has been updated to include details on Trump’s July 7 executive order regarding the implementation of FEOC rules.

On June 30, after an exhausting round of late-night negotiations, Delaware state legislators passed a bill to effectively green-light the Southeast’s second offshore wind farm. Within days, lawmakers in Washington passed legislation that may doom its future.

MarWin, the first phase of a 114-turbine project off the Delmarva Peninsula, is slated for installation in 2028 with onshore construction possibly starting next year, but that timeline is perhaps unrealistic, said Harrison Sholler, an offshore wind analyst with BloombergNEF. MarWin doesn’t have its financing in place yet to underwrite construction and, to make matters worse, Congress just unleashed a crushing new deadline.

When President Donald Trump signed the “Big, Beautiful Bill” on Friday, he dramatically shortened the window in which offshore wind projects can qualify for tax credits that offset up to 30% of their costs. The law now requires new wind farms be “placed in service” by the end of 2027 or begin construction by July 4, 2026, to qualify.

“We don’t predict any new offshore wind projects starting construction … at least in the next four years,” Sholler told Canary Media two days before Congress passed the bill.

He described Republicans’ tightening of the tax credit — from an original deadline to start construction by 2033 or potentially later, to this one-year sprint — as the final nail in the coffin for offshore wind farms that are fully approved but not currently underway. Two projects — MarWin near Maryland and New England Wind off the Massachusetts coastline — float in this gray zone, and are now vulnerable to being put on ice indefinitely.

Wind developers have faced mounting hurdles in recent months: new tariffs, a federal permitting pause, higher investment risk, and the looming threat of the Trump administration halting already-approved projects, like it did in a shocking monthlong pause on New York’s Empire Wind.

A BloombergNEF report released in April states that losing the Inflation Reduction Act tax credits, known as 45Y and 48E, would be “devastating” for U.S. projects already in the pipeline. Analysts estimate that the electricity produced by offshore wind farms that qualify for the credits costs on average 24% less over a project’s lifetime.

That April report predicted “all but the most advanced projects [will] pause development activities.” Now, with tax credits officially rolled back, prospects for offshore wind appear even more dim.

“If you take away the tax credits, it doesn’t make much sense to develop an entirely new sector,” said Elizabeth Wilson, a professor of environmental studies at Dartmouth College who studies offshore wind policy.

America’s offshore wind sector is still in its infancy. While the U.K. has already built over 50 wind farms in its waters, America has only completed one large-scale project: South Fork Wind, located off the coast of Long Island, New York.

Trump issued an executive order on Inauguration Day that froze all offshore wind permitting and leasing pending a federal review. Seemingly safe from the president’s ire at the time were eight projects, including MarWin, that already had all their federal permits in hand. Since then, at least one of those permitted projects — the 2.8-gigawatt Atlantic Shores project off the New Jersey coast — has fallen apart. Five are currently under construction.

The largest offshore wind project now being built in America — Dominion Energy’s 2.6-gigawatt Virginia project — appears unscathed by the Inflation Reduction Act rollback.

“There is no impact to Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind. The project is nearly 60 percent complete and is on schedule to be completed in late 2026,” wrote Jeremy Slayton, a spokesperson for Dominion Energy, in an email to Canary Media, dispelling concerns that the 176-turbine project off the Virginia coastline would suffer from the scaleback of tax credit eligibility.

The existing tax credits Dominion expects to secure “will result in substantial savings for our customers,” he added.

Dominion has so far spent approximately $6 billion on this monumental project. Some in the industry feared that the impact of Trump’s reconciliation bill could have been far worse, and are celebrating that the five wind farms under construction might see full operation.

“While this fight is over, I’m incredibly proud of Oceantic’s members and staff,” said Liz Burdock, president and CEO of the offshore wind industry group, in a July 3 statement after Congress passed the bill. “Because of their relentless push, developers now have one year to start construction and retain 100% of their tax credits, with a simple ‘safe harbor’ option.” (On Monday, Trump issued an executive order that tries to further limit the bill’s “safe harbor” and “beginning of construction” options.)

But for Maryland and Delaware state lawmakers who backed MarWin in the face of considerable county-level pushback in recent months, the “Big, Beautiful Bill” is a major blow. The project’s turbines were slated for installation off Maryland’s coastline but its cables would come ashore in Delaware, making it a much-anticipated joint investment.

On June 30, Delaware’s Democratic lawmakers passed a bill that strips Sussex County officials of their ability to revoke local permits for certain aspects of the wind project. A county-level block on an onshore substation was MarWin’s final hurdle and clearing it meant construction on the substation could, in theory, begin as early as February of next year.

“This bill helps eliminate unlawful and unnecessary hurdles to a project that will help ensure electric reliability for Delawareans while lowering the price they pay for electricity,” Nancy Sopko, a spokesperson for MarWin developer US Wind, told Canary Media via email.

But whether US Wind can lock in financing and officially break ground by July 2026 — the new deadline for tax credit eligibility — is another story. US Wind is suing the Sussex County Council over the permit denial in hopes of starting earlier, before the new state law goes into effect.

Before signing the final bill, Delaware’s Gov. Matt Meyer (D) said it is important to get the offshore wind energy project “done quickly and safely to provide sustainable power to Delaware.” Within days, however, MarWin had potentially been rendered incapable — at least in the view of analysts — of taking advantage of the tax credits that would make its construction financially possible.

President Donald Trump got his “One Big, Beautiful Bill,” and a Fourth of July signing ceremony to boot. America got the removal of 11.8 million people from health insurance programs, tax cuts that mostly benefit the wealthy — and the dissolution of both longstanding and newly erected pillars of energy and industrial policy.

The One Big, Beautiful Bill Act is a law not of creation but destruction. It’s the antithesis of former President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better Act, which was ultimately pared down into the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022. That law sought to push America toward the future, toward clean energy. This new law tethers the country to the past, to coal and oil and gas.

It eliminates a set of subsidies that have, over decades, helped solar and wind mature from niche technologies to cornerstones of our power grid. It scraps tax credits for rooftop solar, electric vehicles, and heat pumps, making it more expensive for the average person to buy these cleaner options. It threatens to pull the rug out from under manufacturers who, encouraged by the incentives created by the Inflation Reduction Act, had chosen to build new factories to make products like solar panels and lithium-ion batteries in the United States.

Jobs will be lost. Energy will get even more expensive. Billions more tons of carbon dioxide will escape into the atmosphere, needlessly, trapping more and more heat under the lid of a planet that is already boiling over.

Though dozens of congressional Republicans voiced their support for various clean energy subsidies in recent months — and though Republican congressional districts benefit most from the manufacturing boom the incentives have created — Trump’s signature legislation ultimately faced almost no resistance. Browbeaten by the president, every GOP lawmaker who had signed onto letters supporting clean-energy incentives voted for the law, save one. That lone holdout was Sen. Thom Tillis of North Carolina, who had announced his retirement days before.

In effect, the new law repeals much of the Inflation Reduction Act, a landmark law that was not only helping the United States reduce its carbon emissions, but also gave the country a much-needed injection of industrial policy. It was a rare, coherent attempt to marshal the might of the U.S. government to boost an industry — in this case, clean energy — deemed critical to national interests.

That policy was working.

After the law went into effect and introduced a new subsidy for clean-energy factories, the long-stagnant U.S. manufacturing and industrial base began to undergo a remarkable revitalization.

Firms unveiled plans to invest more than $100 billion to build solar-panel and EV and battery factories that would create an estimated 115,000 jobs. Construction spending on U.S. manufacturing facilities grew far faster than it has since the turn of the century. One major metal company announced plans to build the first new aluminum smelter in the U.S. in 45 years, the result of an ambitious Biden-era program that sought to power heavy industrial processes without fossil fuels. That same program spurred plans for futuristic new steel plants that would operate without coal. The Trump administration dismantled that program in May, and the fate of those projects remains unclear.

The Inflation Reduction Act greatly accelerated the development of clean energy. This trend was underway before Biden’s law went into effect, thanks to a pair of tax credits, one of which dates back to George H. W. Bush’s administration and the other of which to the second term of George W. Bush. Biden’s signature climate law took these existing policies and expanded them, turbocharging the already-rapid rise of renewables. The results speak for themselves: As of last year the U.S. now gets more electricity from wind and solar than from coal. Big grid batteries have helped Texas and California keep the lights on during heat waves.

Now, with the repeal of those and other incentives, it’s expected that the U.S. will plug somewhere between 57% and 72% less clean energy into the grid over the next decade. Because clean energy accounts for nearly all new electricity capacity built in the U.S., it’s unclear what, if anything, would fill in that gap. It won’t be new gas-fueled plants — turbine orders are severely backed up. The solar, wind, and battery projects that do get built will be more expensive because the clean-energy subsidies are now gone. Those higher costs will be passed on to households and businesses, exacerbating the energy inflation Americans are already dealing with.

The timing could not be worse. Around the country, demand for electricity is anticipated to grow at a pace not seen in years. One of the biggest drivers is the proliferation of data centers that underpin increasingly popular AI systems like ChatGPT — and can use as much power as a small city. Making energy scarce right when it’s needed most will put even more upward pressure on power bills. And without abundant electricity, the U.S. will struggle to compete with China on AI.

China already dominates all things clean energy, making and installing more of all its various forms than most other countries combined. The Inflation Reduction Act was meant to help the U.S. wrest some control back from China in those technologies. The One Big, Beautiful Bill Act will instead put the U.S. further behind on clean energy, and possibly AI too.

It’s difficult to square the destruction of these policies with Republicans’ stated priorities.

The GOP and Trump himself have repeatedly extolled the virtues of affordable and abundant energy. They’ve spoken about the need to bring manufacturing jobs back to America. They say they want to maintain economic competitiveness with China, and certainly want to come out ahead in the AI race.

And yet the One Big, Beautiful Bill Act will essentially eliminate the only industrial policy the U.S. had in place to enable it to accomplish those goals.

Maybe the fossil fuel money, which has flowed toward Republicans and Trump like an oil spill, explains this behavior. Or perhaps, as writers like Derek Thompson have suggested, all of this is simply about owning the libs. Certainly fear of crossing Trump forced Republicans to fall in line. He wanted badly to extend his tax cuts, and slashing clean energy will help pay for a tiny portion of doing so.

Some congressional Republicans have reasoned that solar, wind, EVs, and other forms of clean energy are mature enough to no longer need subsidies. It’s true that these technologies have come a long way, but fossil fuels continue to receive hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies in the U.S., according to the International Monetary Fund. There are no signs that this spigot will be turned off. In fact, the GOP’s bill will toss one slice of the industry another $150 million each year in direct subsidies.

Whatever the reason, the effect is clear. The U.S. under Trump has hitched itself to fossil fuels, to combustion, to literally ancient forms of energy that more forward-thinking countries will be leaving behind in the coming decades. For reasons economical as much as ecological, the future will be dictated by clean energy.

Dean Solon stands out as one of the very few self-made billionaires to emerge from the U.S. solar industry, following the tremendous 2021 initial public offering on the Nasdaq of his solar-equipment firm Shoals.

But a few weeks ago, as he and I found seats outside the Midwest Solar Expo in a far western suburb of Chicago, it was clear the major cashout hadn’t changed his style. Solon, age 61, was dressed not in Balenciaga or Louis Vuitton, but his trademark jean shorts and athletic sneakers.

“I’m gonna go from a large Dunkin Donuts to an extra-large Dunkin Donuts now,” he said. “I still, to this day, drive a 2017 Chevy Bolt, 100% electric. I still live in the same house. I didn’t do it for the money then, I don’t do it now.”

In fact, Solon’s instinct to tinker and solve problems has thrust him back into the solar manufacturing space at the industry’s most chaotic moment in years.

“The renewables building is on fire, and it is hot as fuck, and everybody’s running away from the fire,” he said. “We have asbestos-clad underwear on. We have our fire suit on, and we got a hose, and we’re running into the fire.”

Solon has decided to compete in these dire circumstances by essentially building the entire menu of items needed for a modern solar, battery, or microgrid project, and designing all the pieces to fit together seamlessly. His new firm, Create Energy, will sell developers solar modules, trackers, batteries, inverters, power stations, and other auxiliary equipment. The goal is to save customers time and effort compared to buying separately from a tracker vendor, a module vendor, an inverter vendor, and so on, and then assembling all those components with separate crews.

It’s an ominous time to start a new solar manufacturing business in America, to say the least. After a booming few years following the implementation of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act and its various, generous clean-energy manufacturing incentives, firms now find themselves squeezed between fluctuating tariffs and the detonation of those same incentives, following President Donald Trump’s signing of the One Big, Beautiful Bill Act last week.

What better moment to check in with one of the most singular voices in the solar industry, who has survived and thrived through the solarcoaster of the last two decades without wavering in his commitment to American manufacturing?

Solon’s previous company Shoals originally made automotive parts for Bosch back in the ‘90s. But after the North American Free Trade Agreement went into effect, lifting most tariffs between Canada, the U.S., and Mexico, Bosch wanted to relocate its suppliers to the latter nation, and Solon refused to move his operation out of Tennessee, he recalled.

Around that same time, he got an inbound request from a budding solar enterprise that needed some manufactured junction boxes and cable assemblies; that upstart turned out to be First Solar, pretty much the only U.S. panel manufacturer that has excelled over the last few decades (and whose stock has been on a tear as Congress prepared to revoke tax credits for solar projects that use Chinese-made materials).

Once he made the jump into solar equipment in the early 2000s, Solon kept manufacturing in America, even as installers and developers embraced cheaper Chinese products and U.S. cell and module manufacturing collapsed.

“Solar makes sense, with or without incentives; Buying American-made products, even better,” Solon said. “Listen, I fly the American flag like crazy. I grew up in the ‘70s working on American cars. I’m a gearhead my whole life. I love American-made products, and I’m gonna push it.”

That ethos continues in the new venture. The strategy is to build high-quality equipment and find customers who understand its value, because they’re investing with a longer-term mindset.

“We’re not looking for every Tom, Dick, and Harry that’s trying to flip a project to build it as cheap as possible with garbage,” he said. “I’m looking for the [independent power producers], the big power companies, who want to buy systems that are going to last for decades.”

In theory, a company with this attitude would welcome tariffs, which raise the cost of cheaply produced competition from Chinese factories. The last few months have seen new tariffs aplenty, though Trump has waived some within days or weeks of announcing them. But while tariffs are often billed as helpful to domestic manufacturers, President Trump’s tariffs are also causing complications for the American factory buildout.

For starters, Trump’s blanket tariffs on all Chinese goods impact manufacturing equipment produced in that country. Not only does China make most of the world’s solar panels — it also makes many of the machines required to manufacture solar.

“To be clear on this point, there’s no better-built machines for solar than Chinese equipment, end of story,” Solon said. “That’s how good it is. It’s heads and tails better than anywhere else you could get machinery.”

“It was easy to order machinery, but then once the tariffs hit, there’s a lot of machinery just sitting in ports in China that hasn’t left,” he added.

Even if Solon could get his hands on that equipment without exorbitant price hikes, the U.S. lacks enough production of solar cells — the component that actually converts sunlight into electricity — to meet the demand for domestic module assembly. Factories that can’t obtain the limited domestic cells need to import them, but the so-called reciprocal tariffs Trump has announced on much of the world, and then delayed, have scrambled the economics for cells from outside the U.S.

Create is making other products at its Portland, Tennessee, factory, but the timeline for making solar modules in-house has been pushed back due to the macroeconomic headwinds.

A decade ago, solar module costs started to plunge, and the price of solar-generated power fell along with it. That has propelled solar to the front of the pack for new power plant construction. But lately the slope of cost declines has leveled off, and incremental module improvements do less and less to push the cost of solar power lower.

Solon is stepping into that mature marketplace, so he has to bring something new to the table to stand out. After years of making the electrical connectors needed to hook up solar panels into a functioning power plant, he realized he could eliminate several steps for installers with clever design hacks.

Today’s standard solar-plant construction process creates inefficiencies. “Everyone is this separate crew working on the same rows over and over and over ‘til they do it in the next location,” Solon said.

A singular project might have different crews clear the earth, pound the posts, add torque tubes, bolt the modules in place, check the torque on the bolts, handle the electrical work, and then clean up the site, he said.

The new products from Create come with electrical connections pre-wired into the modules and the torque tubes of the trackers. Installers can easily snap everything together, at which point, Solon insists, the systems won’t need any more maintenance.

Solon’s goal was to make installation so easy that it would be doable for an avatar of the modern man that he refers to as “Mr. Hot-Pocket Muncher,” who is “happy living in mommy’s basement eating Hot Pockets and playing 12 hours of Xbox.”

“Take my module, and grab Mr. Hot-Pocket Muncher,” Solon envisioned, after showing me an AI rendering of the character, which his colleague on hand advised him against making available for publication. “He picks it up. He clicks it on the torque tube. Did I hear it click? Yes, I’m done. Grab the next one. Click, yes. All the wiring is done. All the mechanical connections are done, and they’re non-serviceable. There’s nothing for an [operations and maintenance] crew to ever do again.”

That vision would threaten a number of specialized jobs in the solar installation and maintenance business. But it would also deliver more efficient construction, so the same workforce could theoretically deliver more clean power in the same amount of time. If Solon can pull it off, that kind of benefit could be valuable as the industry stares down the loss of its decades-long tax-credit regime.

Solon doesn’t deny that the solar industry writ large is heading for a contraction, but he rejects the more apocalyptic outlooks some fear for the sector. Instead, he thinks it’ll be a reset for the industry after the bounty of Biden-era policy supercharged the pace of activity.

“Right now, the solar business is a drunk pirate that partied like a rock star all last night,” Solon mused. “We woke up, we’re hung over as hell, and we’re reaching for our wallet and our keys, and we can’t find either one of them. And we wonder what the hell happened? I think we’re gonna be hung over for about six months to a year.”

The wave of bankruptcies has already begun, taking down longtime industry stalwarts like solar loan provider Mosaic, rooftop solar financier Sunnova, grid-battery integrator Powin Energy, and more.

It’s not a bad time to have a billion dollars in the bank and several decades of manufacturing experience.

“If you’re in a consolidated market [and] people are going out of business, who are you going to run to to get your products and services?” chimed in Create’s chief of staff, Joe Fahrney, who was sitting next to Solon at the Midwest Solar Expo. “So people are lining up to buy from Dean Solon, because they know Dean and Create will be in business over the next 20, 30, 40, 50 years.”

“This time it won’t IPO though,” Solon interjected. “I’m not giving up control, because I want this little baby to run for hundreds of years.”

Two years after the last attempt to build out wind farms in Maine’s northern reaches fizzled, the state is again gearing up to seek developers to build at least 1,200 megawatts of land-based wind capacity and a transmission line to carry the electricity produced to the central part of the state. At the same time, grid operator ISO New England is accepting proposals for new transmission infrastructure that will allow that power to flow to the rest of the region.

For wind power advocates, these moves have sparked hope that a new source of renewable energy may finally be developed in the region.

“After talking about this for the last 15 years, I feel like there’s a light at the end of the tunnel,” said Francis Pullaro, president of clean-energy industry association RENEW Northeast. “It’s definitely complicated and a big undertaking, but I think the state has realized what a great opportunity northern Maine wind provides.”

Maine and most of its neighboring states have ambitious emissions-reduction targets: Maine just adopted legislation calling for 100% clean energy by 2040, for example, and Massachusetts and Rhode Island both aim to be carbon-neutral by 2050. Offshore wind has been a major part of the states’ strategies for transitioning away from a system that now leans heavily on natural gas for electricity generation. However, as the Trump administration throws up roadblocks to offshore wind development, it becomes even more important to tap into land-based wind to keep progressing toward a cleaner energy future, supporters said.

“It’s a really important medium-term piece of the puzzle in how we reduce our dependence on gas as a region and for our state,” said Jack Shapiro, climate and clean energy director for the Natural Resources Council of Maine, an environmental advocacy group. “It’s a pretty big deal.”

Plans to build onshore wind in northern Maine’s remote Aroostook County have come and gone several times over the past two decades. In 2008, then-Gov. John Baldacci (D) signed a law setting a goal of bringing 2,000 MW of wind power online by 2015 and 3,000 MW, including some offshore wind, by 2020. As of this year, the state has 1,139 MW of onshore wind operational and no offshore turbines.

Aroostook County — with its strong winds and low population density — has long been considered a prime area for building turbines, but its promise has not been realized. One of the major obstacles has been the lack of transmission lines to carry power from the forests of northern Maine to the lightbulbs and dishwashers of Massachusetts and Connecticut. Most of Aroostook County is served by an electrical system connected only to Canada, with no direct links to any U.S. power grid. Building the needed lines is a complex, costly undertaking that has repeatedly stymied efforts to get wind generation up and spinning.

“For the southern New England states where all the load is, [northern Maine] always was a fairly distant resource,” Pullaro said. “The lack of transmission has always been the barrier.”

In 2013, Connecticut selected a planned wind development in Aroostook County — EDP Renewables’ Number Nine Wind Farm — to provide 250 MW of power to the state. By the end of 2016, the project had been cancelled, with EDP citing the lack of transmission capacity to get the electricity to customers farther south.

In the final days of 2022, Massachusetts agreed to buy 40% of the power generated by the proposed King Pine wind farm in Aroostook County, a deal that seemed to give the 1,000-MW project the financial security it needed to proceed. By the end of 2023, however, a separate agreement with LS Power to build a transmission line connecting the development to the rest of New England fell through over pricing disagreements, undermining the prospect of wind development.

“The contract negotiations were not successful, and the project stalled,” said Dan Burgess, director of the Maine Governor’s Energy Office.

Now the state has gone back to the drawing board. This time around, however, the plans are getting an unprecedented boost from ISO New England. The regional grid operator in late March issued a request for proposals for the development of a transmission project connecting the Maine town of Pittsfield to points farther south in New England, shortening the distance the power lines from future Aroostook County wind farms will have to travel. A plan could be chosen as soon as September 2026.

Meanwhile Maine utilities regulators released a request for information to collect feedback from developers, industry members, and other stakeholders to help plan and schedule its next procurement. There has been a robust response to the request, though most comments were filed confidentially, said Susan Faloon, spokesperson for the Maine Public Utilities Commission. The tentative plan is to open up for proposals by the end of the year, she said.

Whether the next attempt will be successful hinges on a few factors, starting with its ability to financially weather Republicans’ scaleback of federal clean-energy tax credits and the administration’s continued, evolving hostility to renewable energy projects. Trump halted federal permitting and leasing for wind projects on his first day in office, and although 99% of onshore wind farms are built on private property, they still could need environmental permits from the administration.

“The economics of any specific project is really uncertain right now because we don’t know what will happen,” Shapiro said.

Still, Pullaro said, history suggests that onshore wind development could survive the blow of losing federal support. The grid needs more energy, and land-based wind is one of the least expensive power sources to build, even without incentives, while the cost of new natural gas generation is going up, according to a recent report from investment bank Lazard.

“From the industry point of view and for consumers, wind is still a good deal no matter where the tax situation is,” Pullaro said.

Tweaks to the state’s timeline for issuing a request for proposals and choosing a project could also increase the likelihood of success, Pullaro said. A wind development stands a much better chance of succeeding, he said, if another state commits to buying power from it, giving it a revenue stream it can count on. Getting Massachusetts on board could be even more crucial than federal support, he said.

Massachusetts is still authorized to enter into another such agreement until the end of the year, and Gov. Maura Healey (D) included in a supplemental budget bill a provision that would extend this authorization to 2027, but the legislation is still pending. In the meantime, if Maine waits until the end of 2025 or into 2026 to launch a new solicitation, the eventual development could lose its chance to secure a deal with Massachusetts. Pullaro, therefore, would like to see Maine issue a request for proposals by September.

“The economics don’t work for Maine going it alone,” he said.

Congress moved one step closer to passing President Donald Trump’s “One Big, Beautiful Bill” this week — and with that, one step closer to spiking power bills across the nation.

The bill would rapidly phase out tax credits for clean energy, slowing the construction of solar, wind, and battery projects, which made up over 90% of new electricity connected to the grid last year.

Repealing those tax credits would come at a steep cost to utility customers in every state, according to NERA analysis commissioned by the Clean Energy Buyers Association. The most impacted states could see electricity prices rise by nearly 30% by 2029.

The Senate bill passed Tuesday would require solar and wind projects to either start construction within a year of the bill’s passage or start service by the end of 2027 to receive the tax credits. Those that begin construction after this calendar year would be subject to “foreign entity of concern” restrictions so difficult to comply with that experts have said they amount to a “backdoor repeal.” Batteries, nuclear, and geothermal have a longer runway to claim the credits but would have to deal with the same unworkable foreign-entity strictures.

The bill is now being considered by House Republicans, who have set a self-imposed deadline of sending the bill to Trump’s desk by Friday. A previous version of the bill passed the House in May by just one vote.

Clean energy is the cheapest and easiest way to get power onto the grid. With demand for electricity nationwide rising due in large part to AI data centers, swiftly bringing affordable energy online is more crucial than ever.

But if tax incentives are repealed, fewer solar, wind, and storage projects will be built. Between now and 2035, the U.S. could see 57% to 72% less new clean-energy capacity come online than it would have with the tax credits in place, according to Rhodium Group. Meanwhile, new gas construction likely can’t make up the difference in the near term: Developers who want to build new gas power plants face wait times of up to five to seven years for turbines.

Rising power demand plus slower power-plant construction is a recipe for higher electricity bills.

Households and businesses in Wyoming, Illinois, and New Mexico would see the biggest jump in energy costs should the tax credits be repealed. Nationwide, electricity prices would increase by an average of 7.3% for households and 10.6% for businesses, worsening the increasingly steep energy costs Americans face.

The biggest loss, however, would be for attempts to decarbonize the U.S. power system. The Inflation Reduction Act, the U.S.’s first real stab at climate policy, had put the country nearly on track to cut carbon emissions in line with global climate commitments. Under this bill, however, U.S. efforts to move away from fossil fuels are certain to be slowed — even as the rest of the world speeds ahead toward clean power.

Canary Media’s “Electrified Life” column shares real-world tales, tips, and insights to demystify what individuals can do to shift their homes and lives to clean electric power.

As summer temperatures sizzle, are you frantically shopping for central air conditioning? Take a breather, because you could get AC functionality — and more — by opting for an increasingly popular appliance: a heat pump.

All-electric heat pumps are ACs, but better. Equipped with the ability to work in reverse, they not only dump heat outside in the summer, but can also pull heat indoors in the winter.

Heat pumps do often cost a bit more up front, but if you’re on the hunt for a new AC system anyway, the difference can be small enough that it’s worth exploring the option. After all, you could end up with AC and a shiny new heating system, to boot.

Should you join the growing share of households choosing heat pumps over mere ACs? Here are answers to key questions a prospective buyer is likely to have.

When sized right, heat pumps let you simultaneously meet your cooling needs and proactively upgrade your heating system to one that’s better for your health and, typically, your wallet in the long run.

For most households, these two-in-one appliances pay for themselves in reduced energy bills over their estimated 16-year lifetime.

Families that go from relying on expensive delivered fuels to electric heat pumps unlock the biggest cost savings: an average of $840 per year, according to electrification nonprofit Rewiring America. Households ditching gas heating can see an average of $60 in savings per year. Utility customers with access to electricity rates that favor heat pumps can save even more.

Other benefits? Heat pumps slash planet-warming pollution. Adopters report that the appliances produce more even, comfortable heat than gas systems. And unlike their fossil-fuel-burning counterparts, heat pumps don’t emit pollutants linked to asthma, cancer, and premature death.

Oh, and if you’re okay with air-handling units on your walls, a mini-split heat pump system can let you get AC without having to install pricey ductwork.

It’s tricky to find trustworthy data about the cost of central AC, home-energy marketplace EnergySage reports. But the general consensus is that heat pumps do come at a bit of a premium.

Here’s one example: In California, it costs between $900 and $1,900 more to replace a broken central AC with a heat pump instead of a conventional AC. That’s out of a median total heat-pump installation cost of $15,900, per data from the TECH Clean California program from July 2021 to April 2024.

But spending on a heat pump can mean avoiding the expense of getting a new furnace. Southern California’s air-quality agency recently found that installing a heat pump in a single-family home in the region typically costs $1,000 less than installing a gas furnace and AC.

Across the U.S., heat pump installations typically fall between $6,600 and $29,000, according to Rewiring America. That wide range is because project prices for heat pumps, like other HVAC equipment, can depend on a dizzying number of factors, including the size of your home, its energy demand, your local climate, the equipment efficiency rating, the state of your home’s electrical system, and how familiar your local labor market is with the product.

For now, there’s the Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit, which can take up to $2,000 off your federal tax bill for a qualifying heat pump. But if Republicans’ “Big, Beautiful Bill” passes in its current form, that tax credit will disappear at the end of this year. (All the more reason to get one this summer.)

Income-qualified households can check with their state energy office about the availability of Home Energy Rebates, an $8.8 billion initiative created under the landmark 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. Details vary by state, but the law established an $8,000 incentive for a heat pump, as well as rebates for enabling updates: $2,500 for electrical wiring and $4,000 for an electrical panel upgrade. While some state programs have rolled out after being finalized under the Biden administration, others still awaiting approvals are now stuck in limbo.

Separate state and local incentives may also be available. Ask your utility, Google, and reputable heat-pump contractors in your area. Rewiring America also has a handy calculator that provides information on electrification incentives for residents in 29 states, with more soon to come, a spokesperson said.

Get at least three quotes; the EnergySage marketplace can connect you to vetted local installers so you can compare offers. Some contractors specialize in home electrification — and might offer cutting-edge strategies to navigate a heat pump transition. Utility and local incentive programs may also have lists of participating installers.

But don’t stop there. See if there’s a local electrification group — like Go Electric Colorado, Electrify Oregon, or Go Electric DMV for D.C, Maryland, and Virginia — which can connect you to resources and friendly, knowledgeable electric coaches. Typically volunteers, they can offer free advice and recommend contractors they’ve worked with.

Ideally, you don’t want to find yourself in the sticky and sometimes downright dangerous situation of needing to get your AC replaced in an emergency. But if your AC has suddenly expired, you can give yourself more time to weigh your options by getting a “micro” heat pump as a stopgap measure.

Experts recommend drafting a road map for electrification upgrades in advance. Research contractors, costs, incentives, and logistics of other upgrades, like insulation and air-sealing or electrical system updates; your future self will thank you.

To help you on your electrification journey, Rewiring America offers a free, personalized planning tool, complete with estimated energy-bill impacts.

Changing your HVAC system is a big deal — and you don’t have to figure it out on your own. Got a question or story to share about choosing a heat pump over an AC, tackling another electrification project, or fully electrifying your home? I’d love to hear it! Reach out to me at takemura@canarymedia.com; my aim is to make the energy transition easier for you. Stay cool out there!