In 2017, the early leaders in energy storage made an audacious bet: 35 gigawatts of the new grid technology would be installed in the United States by 2025.

That goal sounded improbable even to some who believed that storage was on a growth trajectory. A smattering of independent developers and utilities had managed to install just 500 megawatts of batteries nationwide, equivalent to one good-size gas-fired power plant. Building 35 gigawatts would entail 70-fold growth in just eight years.

The number didn’t come out of thin air, though. The Energy Storage Association worked with Navigant Research to model scenarios based on a range of assumptions, recalled Praveen Kathpal, then chair of the ESA board of directors. The association decided to run with the most aggressive of the defensible scenarios in its November 2017 report.

In 2021, ESA agreed to merge with the American Clean Power Association and ceased to exist. But, somehow, its boast proved not self-aggrandizing but prophetic.

The U.S. crossed the threshold of 35 gigawatts of battery installations this July and then passed 40 gigawatts in the third quarter, according to data from the American Clean Power Association. The group of vendors, developers, and installers who just eight years ago stood at the margins of the power industry is now second only to solar developers in gigawatts built per year. Storage capacity outnumbers gas power in the queues for future grid additions by a factor of 6.5, according to data compiled by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

“Storage has become the dominant form of new power addition,” Kathpal said. “I think it’s fair to say that batteries are how America does capacity.”

Back in 2017, I was covering the young storage industry for an outlet called Greentech Media, a beat that was complicated by how little was happening. There was much to write about the “enormous potential” of energy storage to make the grid more reliable and affordable, but it required caveats like “if states change their grid regulations to allow this new technology to compete fairly on its merits, yada yada yada.”

Those batteries that did get built in 2017 look tiny by today’s standards. The locally owned utility cooperative in Kauai built a trailblazing 13-megawatt/52-megawatt-hour battery, the first such utility-scale system designed to sit alongside a solar power plant. And 2017 saw the tail end of the Aliso Canyon procurement, a foundational trial for the storage industry in which developers built a series of batteries in Southern California in just a handful of months to shore up the grid after a record-busting gas leak — adding up to about 100 megawatts.

“You saw green shoots of a lot of where the industry has gone,” said Kathpal.

California passed a law creating a storage mandate in 2010, then found a pressing need for the technology to neutralize the threat of summertime power shortages. Kauai’s small island grid quickly hit a saturation point with daytime solar, so the utility wanted a battery to shift that clean power into the nighttime. These installations weren’t research projects; they were solving real grid problems. But they were few and far in between.

Kathpal recalled one moment that encapsulated the storage industry’s early lean era. At the time, he was developing storage projects for the independent power producer AES. One night around midnight, he parked a rented Camry off a dirt road and pointed a flashlight through a sheet of rain. It was his last stop on a trip to evaluate potential lease sites for grid storage ahead of a utility procurement — looking at available space, proximity to the grid, and stormwater characteristics. But once the utility saw the bids, it decided not to install any batteries after all.

“The storage market is built not only from Navigant reports but also from moments like that,” he said. “We had to lose a lot of projects before we started winning.”

Now that same utility is putting out a call for storage near its substations — exactly the kind of setting Kathpal had toured in the rain all those years ago.

Indeed, many of the projects connected to the grid this year started with developers anticipating future grid needs and putting money on the line for storage back around the time ESA was formulating its big goal, said Aaron Zubaty, CEO of early storage developer Eolian.

“Eolian began developing projects around major metro areas in the western U.S. starting in 2016 and putting the queue positions in that then became operational in 2025,” Zubaty said. The 200-megawatt Seaside battery site at a substation in Portland, Oregon, is one example.

Though the storage industry pioneers somehow nailed the 35-gigawatt goal, market growth defied their expectations in several important ways.

ESA had expected more of a steady ramp to the 35 gigawatts, said Kelly Speakes-Backman, who served as its chief executive officer from 2017 to 2021. But the storage market ran into plenty of false starts, such as when states passed mandates to install batteries but never enforced them, and when federal regulators ordered wholesale markets to incorporate storage but regional implementation dragged on for years.

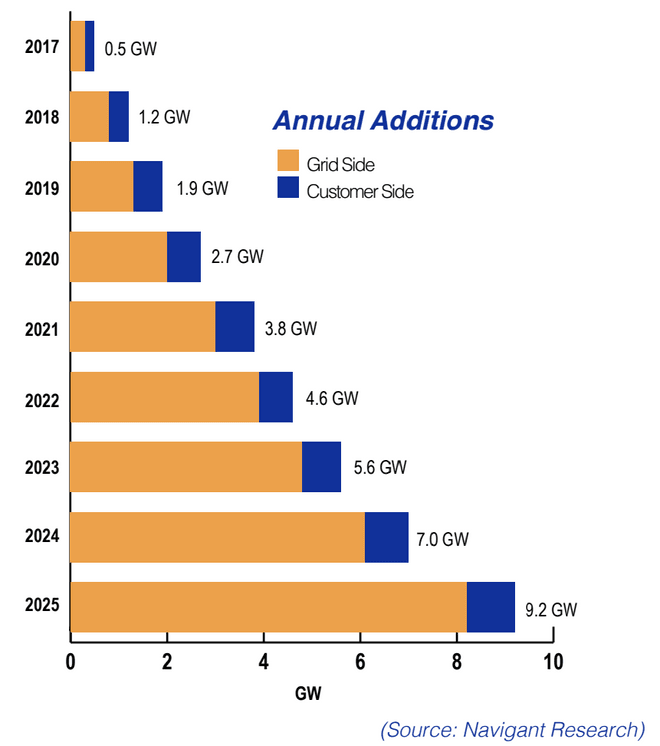

The ESA report predicted that 2018 deployments would cross the 1-gigawatt threshold, which didn’t actually happen until 2020. But real installations significantly outpaced the expected numbers in the run-up to 2025. The group hoped to hit 9.2 gigawatts installed this year, and instead the industry is on track to deliver 15 gigawatts.

“Once it hit, it really hit,” Speakes-Backman said.

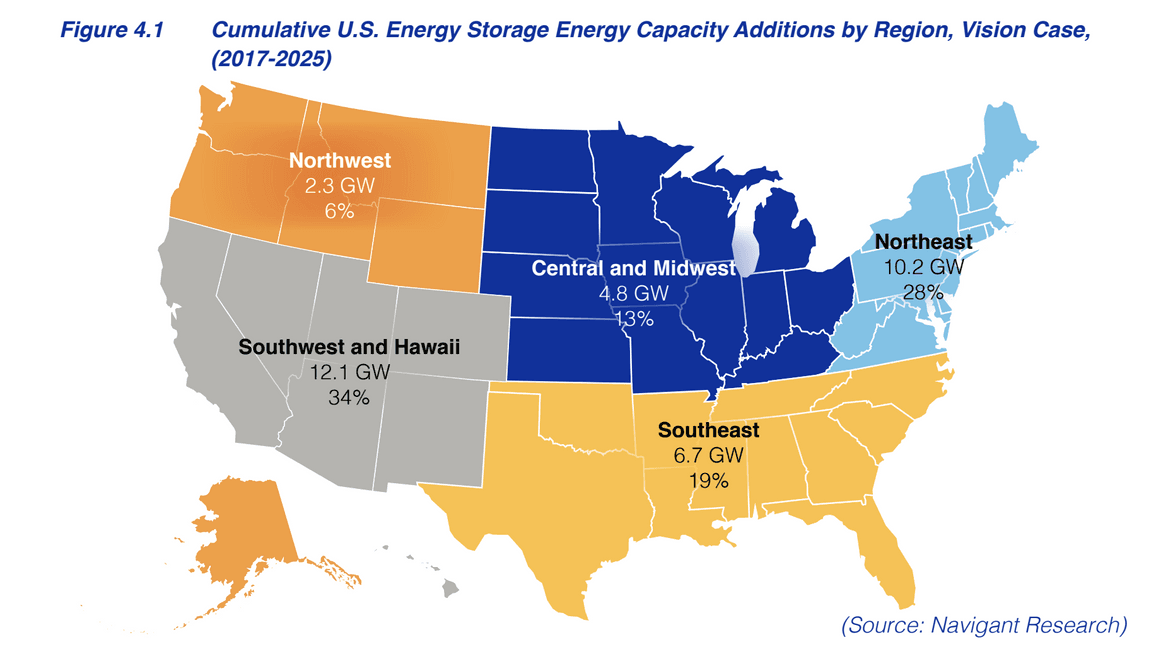

The regional breakdown of storage growth didn’t play out as ESA expected, either. The analysis anticipated that the Northeast would install more than 10 gigawatts, nearly as much as the Southwest (including California and Hawaii); after all, it noted, New England states had passed “aggressive greenhouse gas reduction policies.”

In fact, the Northeast has done exceedingly little to build large-scale storage. (Zubaty told me that “largely dysfunctional power markets combined with utilities that have excessive regulatory capture” thwarted many good battery projects there.)

But other regions surpassed ESA’s expectations. California, Texas, and Arizona alone hold roughly 80% of all U.S. battery storage capacity. This lopsided concentration of storage could be seen as a weakness of the industry. Noah Roberts, executive director of the recently formed Energy Storage Coalition, which advocates for storage in federal arenas, said the pattern reflects how storage has sprung up in spots that suffer acute grid stress.

“Where energy storage has been deployed to date, it is and has been concentrated in areas that have had the greatest reliability need,” he said. “That is Texas and California, where in the early 2020s there were blackouts or brownouts that were quite significant.”

Now, Roberts said, other regions can look at California and Texas for empirical data on how the storage influx has helped reliability while lowering grid costs, for instance by avoiding power scarcity during heat waves and pushing down peak prices. “We’re really seeing the broadening of the geographic footprint of energy storage deployment,” he said, to regions like the Midwest and the mid-Atlantic, which are grappling with unanticipated load growth.

Indeed, the ESA did not foresee the artificial intelligence boom sending power demand through the roof. Instead, its report predicted, “Electrified transportation will likely provide the largest source of new system load.” Now the storage industry has emerged as the biggest player in constructing firm, on-demand power plants, at the exact time that rapid power construction has become the key limiting factor in the AI arms race.

The storage market outdid expectations in one other major way. In 2017 the storage industry was intently focused on getting batteries installed, not so much on where they came from. Since then, bipartisan sentiment has shifted from unfettered global trade to a distinct preference for American manufacturing. The U.S. has made batteries for electric vehicles for years now, but the lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries favored for grid storage have come almost exclusively from China. Now manufacturers are opening domestic cell production for grid storage, just in time for new rules that constrain federal tax credits for battery projects with too much material from China.

LG Energy Solution opened a factory to produce battery cells for grid storage in Michigan this summer that is capable of producing up to 16.5 gigawatt-hours at full capacity; the company expects to raise its North America capacity to 40 gigawatt-hours by the end of 2026. “All of our projects integrated before 2022 combined are smaller than some of our newer individual projects,” noted Tristan Doherty, chief product officer of LG Energy Solution subsidiary Vertech, which focuses on grid batteries.

Tesla is opening domestic LFP battery fabrication in 2026. Fluence announced the first shipment of its “domestically manufactured energy storage system” in September. Newcomers with novel chemistries for longer-duration storage are joining the fray, such as Form Energy and Eos Energy, both of which operate factories outside Pittsburgh.

“By the end of next year, we anticipate reaching the milestone of producing as many domestic energy storage battery cells as we need for demand,” Roberts said. “That is a pretty miraculous story that not many industries have the ability to say they’re able to accomplish.”

The storage industry was vindicated in stretching its aspirations beyond what many thought was possible. Those early adopters knew their technology was valuable, but even they didn’t guess how it would connect with the generational forces reshaping the U.S. economy, from AI to the onshoring of industry.

A clarification was made on Dec. 4, 2025: This story has been updated to reflect that LG Energy Solution’s goal to reach 40 GWh of battery-manufacturing capacity is for North America as a whole, not just for the company’s Michigan plant.