American factories use lots of hot water and steam to produce everyday goods like milk, cereal, beer, toilet paper, and bleach. Most facilities burn fossil fuels to get that heat, emitting huge amounts of planet-warming pollution in the process.

Switching to electricity could significantly and immediately slash those emissions in many places, according to a new report by The 2035 Initiative at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Electric versions of industrial boilers, ovens, and dryers are already available, and newer models promise to boost factories’ efficiency and curb energy costs even further.

“We can make progress today with the technologies we have,” said Leah Stokes, an associate professor of environmental politics at UC Santa Barbara and one of the principal researchers for the report.

But electrifying factories is a far more complex undertaking than, say, trading a gasoline-fueled car for a battery-powered vehicle. The process involves making many head-scratching calculations and engineering choices, which is partly why companies have been slow to adopt electrified equipment. Stokes said the report aims to demystify some of those decisions so that U.S. manufacturers can start tackling their heat-related emissions.

“We wanted to answer this question [of] where is it most technologically and economically feasible to electrify industrial process heat today?” she said during a Dec. 16 webinar. The study also drives home the need to rapidly build more clean energy to power all that new demand.

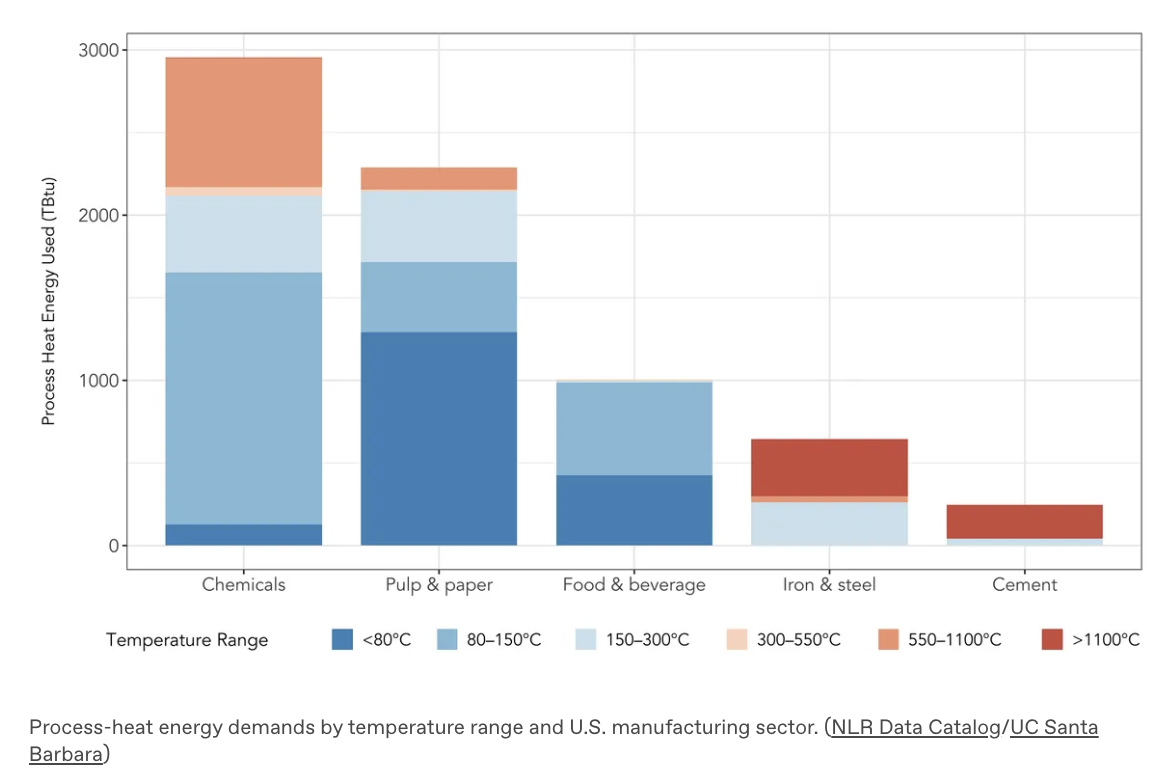

Researchers simulated what it would look like to electrify nearly 800 large industrial plants within three sectors: food and beverage, chemicals, and pulp and paper manufacturing. These facilities use relatively low- and medium-temperature process heat — unlike scorching cement kilns or steel mills — and together account for about 40% of CO2 emissions from the U.S. industrial sector.

The UC Santa Barbara team modeled four scenarios for electrifying each of these plants, beginning with “drop-in electrification” — using electrode boilers and electric ovens and dryers — and progressively expanding efforts to include major energy-efficiency upgrades and advanced technologies, like high-temperature heat pumps from the startups AtmosZero and Skyven.

At the most ambitious level, electrifying these factories could slash the country’s emissions by 1.3 billion metric tons of CO2 equivalent by 2050, while also providing $475 billion in public health benefits by improving air quality, researchers found. The figures assume the U.S. electric grid will be running almost entirely on clean energy by mid-century, up from 40% today.

“This one space actually can contribute an outsize share of the global [climate] mitigation we need to keep our global temperature rise in check,” said Eric Masanet, a sustainability science professor at UC Santa Barbara who led the study with Stokes.

In certain cases, it can cost manufacturers about the same amount of money to get heat from electric systems rather than gas-fired ones, he said. That includes processes that use less intensive heat, like ethanol and plastics production, since heat pumps work more efficiently at lower temperatures. It’s also true for factories located in places where fossil gas is relatively expensive. In Delaware, New York, and Washington state, for example, companies enjoy a more favorable “spark gap” — the difference between electricity and gas utility costs for the same unit of energy delivered.

Just as cost varies by facility, so does the potential for emissions reductions. The largest CO2 savings are in states with low-carbon grids, like Washington, California, and Vermont. In places with dirtier grids, switching to electricity can actually increase emissions in the near term if utilities meet that demand with gas- and coal-fired power plants. But even in those areas, researchers expect that electric equipment installed today will still cut pollution over time as the grid gets cleaner.

For that to happen, factories will need a lot more wind, solar, geothermal, and other carbon-free sources to come online. Electrifying the processes included in the study could require 158 to 301 terawatt-hours of additional power, or about 16% to 30% of the electricity currently consumed by industry. That new load would add to the soaring demand that’s already coming from data centers and electrified homes and vehicles.

“If we want to bring the type of electricity to the industrial sector that it’s going to need … we’re going to need to improve the grid,” Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) said during the webinar, adding that streamlining the federal permitting process would hasten the build-out of new transmission and clean energy projects.

The UC Santa Barbara team outlined other policies that could accelerate industrial decarbonization, particularly for the facilities where electrification is more expensive than burning fossil fuels. A 30% federal investment tax credit or state-level grants would offset the up-front costs of investment in new equipment. A “clean heat” production tax credit would lower operating costs, as would reducing industrial electricity rates.

Stokes noted that, even without such incentives, cleaning up manufacturing would take a minimal toll on consumers’ wallets. Take breweries, which use heat for mashing, boiling, and fermenting ingredients and sterilizing containers. “Our modeling shows that even if electrification doubles the cost of energy as an input to beer production, it’s 1 cent per beer,” she said.

“This is something that we can do, and it’s super important,” she added.

LED light bulbs and TVs. Front-loading washing machines. Energy-lean refrigerators. All were once nascent technologies that needed a push to become mainstream.

Now, California is trying to add über-efficient plug-in heat pumps and battery-equipped induction stoves to that list.

It’s a tall order; today these innovative products cost thousands of dollars and aren’t widely available in stores, unlike their more polluting, less efficient counterparts that burn fossil fuels or use electric-resistance coils to generate heat.

But late last month, the California Public Utilities Commission signed off on a plan to spend $115 million over the next six years to develop and drive demand for the fossil-fuel-free equipment — a first-of-its-kind investment for the state. These appliances, which plug into standard 120-volt wall outlets, don’t need professional installers or the expensive electrical upgrades sometimes required for conventional whole-home heat pumps or 240-volt induction stoves. That ease of installation makes them crucial tools in California’s quest to decarbonize its economy by 2045.

The initiatives to boost plug-in heat pumps and induction stoves are explicitly meant to help put electrification within reach of renters, low-income households, and frontline communities that have suffered disproportionate environmental harms and disinvestment.

“This is an incredible example of what it looks like to center [these] communities,” said Feby Boediarto, energy justice manager of the statewide grassroots coalition California Environmental Justice Alliance. “It’s extremely important to think about the long-term vision of electrification for all homes, especially those who’ve been heavily burdened by pollution. And these initiatives are stepping stones to that vision.”

California’s move comes as the federal government seeks to dismantle efficiency programs and policies even as U.S. energy costs surge. The Trump administration is eliminating federal tax credits for energy-saving home upgrades at the end of the year. Meanwhile, a Republican-sponsored bill making its way through Congress would make energy-conservation standards for appliances more difficult to create — and easier to undo.

California’s initiatives, developed by the commission’s California Market Transformation Administrator (CalMTA) program, are multipronged. They take aim at the whole supply chain, from tech development to distribution to consumer education, said Lynette Curthoys, who leads CalMTA. The initial investment by the world’s fourth-largest economy is expected to deliver about $1 billion in benefits, including avoided electric and gas infrastructure costs, through 2045.

One major goal is to bring the price tag of battery-powered induction stoves way down. Current products from startups Copper and Impulse start at about $6,000 and $7,000, respectively — far more than top-rated gas ranges, which customers can snag for less than $1,000.

As for the heat-pump plan, an essential element will be encouraging manufacturers to develop products for the California market in particular.

One quirk they have to deal with is that windows in the Golden State commonly slide open from side to side or by swinging outward. The most efficient window-unit heat pumps available on the market today, by contrast, are designed to fit windows that open up and down.

To spark better-suited designs, the state intends to create competitions for manufacturers — a strategy that’s worked before.

In 2021, the New York City Housing Authority, along with the New York Power Authority and the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, issued the Clean Heat for All Challenge. The competition pushed manufacturers to produce a window heat pump that could handle the region’s chilly winters, with a promise to purchase 24,000 units for public housing. San Francisco-based startup Gradient and Guangdong, China-based manufacturer Midea made the requisite technological leaps for New York. The state later bumped up its heat-pump order to 30,000 units.

CalMTA, in a similar vein, plans to aggregate demand from multifamily-building owners to entice manufacturers to participate in heat-pump and induction tech challenges. The one for heat pumps is expected to launch in mid-2027. Curthoys said the induction contest will come later, after the administrator makes tweaks required by regulators to the clean-cooking initiative.

Gradient has “been working closely with CalMTA over the past year to support this plan,” said Vince Romanin, the company’s founder and chief technology officer. “We’re thrilled to see a clear, coordinated strategy that benefits both manufacturers and consumers.”

Copper plans to participate in the challenge for battery-equipped induction stoves, said Sam Calisch, founder and CEO at the startup. “Copper is now significantly scaling its manufacturing and distribution to meet demand,” and CalMTA’s initiative is “a key element of this effort,” he noted.

The administrator also aims to incentivize appliance retailers to drive adoption.

“We found that a key influencer of buying decisions are actually the sales associates,” Curthoys said. “Some of our interventions will focus on training sales associates to understand the benefits of induction and encourage customers to buy it.”

CalMTA is running a pilot that started the week of Black Friday and gives sales associates “a small bonus” for every induction stove they sell, Curthoys said. This tactic, one of many, played a role in the successful market-transformation campaign for front-loading clothes washers, the administrator reports: In the late 1990s, the Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance provided retail employees with a typical bonus of $10 for each unit they sold. The alliance’s efforts helped drive these efficient appliances from just 2% of household washer sales in the U.S. in 1993 to 10% in 2000. In 2020, that market share had bloomed to 53%.

CalMTA’s hope is for affordable versions of plug-in heat pumps and induction stoves to be widely available for purchase by 2030.

More appliances could follow. The administrator is working on plans to spur demand for energy-efficient technologies such as heat-pump water heaters, as well as windows and rooftop heat pumps for commercial buildings, Curthoys said.

Ultimately, the state’s investment could benefit households around the country, she noted. “When these [products] become available, they will be suitable for other markets — well beyond California.”

Want to claim thousands of dollars in federal tax credits for electrification upgrades that slash emissions, reduce air pollution, and enhance the comfort of your home? You have just over a month left to get them installed.

In July, Republicans in Congress voted to end two key home-energy tax credits: the Energy Efficient Home Improvement Credit (25C), worth up to $2,000 for updates like an über-efficient heat pump; and the Residential Clean Energy Credit (25D), which takes 30% of the cost of rooftop solar and other clean-energy installations off your federal tax bill. To qualify for the credits, projects have to be done by Dec. 31.

Ditching our fossil-fuel equipment for electric options is an opportunity to land a punch in the climate fight. More than 40% of U.S. energy-related emissions stem from how we heat, cool, and power our homes and fuel our cars, according to the nonprofit Rewiring America. Not to mention, clean alternatives are often cheaper to run than dirty-energy versions.

Still, electrifying our lives can be hard. All-electric home upgrades are often big, complex infrastructure projects. Upfront costs can be steep.

But appliances, like cars, come in a wide range of models with different features and a diversity of price points.

It’s worth spending some time to think through the options — after all, doing so could save you tens of thousands of dollars by avoiding an unnecessary electrical-service upgrade or an overpowered heat pump. But to lock in the federal discounts, you’ll need to get up to speed quickly.

That’s where Canary Media can help. I’ve pulled the most relevant stories from the archives to get you prepped on your home retrofit. Dive in anywhere you like.

Why electrify?

Prep Work

How to Electrify Your Home

Get a Heat-Pump Water Heater

Electrify Your Cooking

Get a Heat-Pump Clother Dryer

Get a Charger for Your EV

Electrify Your Landscape Maintenance

Bank Energy With Home Batteries

Need Inspiration?

Coaching & Tools

The Shortcut

Here’s a last piece of advice to help you fast-track electrification projects so that you can get those federal tax credits. Journalist Justin Gerdes, who writes the wonderfully researched newsletter Quitting Carbon, says this is his No. 1 pointer for anyone planning an all-electric home retrofit:

“Search for a specialist electrification contractor you can trust.”

To make that process easier, Rewiring America and the BetterHVAC Alliance launched the National Quality Contractor Network in September. The associated directory is full of certified installers who know and love heat pumps, heat-pump water heaters, insulation, EV chargers, and more.

Gerdes’ advice is golden in a world with or without federal tax breaks. The U.S. government continues to fund state-run home energy rebates for lower-income households. And you can still find a bonanza of state, local, and utility incentives to break up with fossil fuels.

It’s also still early in the adoption curve for many of these electrified technologies. As they become more commonplace, we could see prices drop.

So while now is a great time to invest in electric appliances and reap the benefits of a clean-energy dream home, 2026 — and the years to come — will be too.

New York looks to be waffling on its commitment to ditch fossil fuels in new buildings.

In July, the state became the first in the nation to require all-electric appliances for most new construction. The rules, set to take effect on Dec. 31, would help New York reach its climate goals while slashing energy and health costs for its residents, according to several analyses. Modeling by the state’s grid operator shows that the grid can handle the added demand from electrifying new buildings.

But last week, 19 state assemblymembers — all Democrats — sent a letter to Gov. Kathy Hochul arguing that the all-electric building standard threatens affordability and the grid isn’t ready.

“While I share the long-term goal of decarbonizing our state, I believe the imminent requirement to mandate all-electric new buildings must be paused pending thorough reassessment of grid reliability, cost impacts, and risk mitigation,” wrote Assemblymember William Conrad, who led the petition.

Delaying implementation would buck a timeline set by the 2023 All-Electric Buildings Act, the law that required the state to put together rules for zero-emissions construction.

Hochul, a Democrat, said at a recent press event that she would seriously consider the assemblymembers’ request. “I’m going to look at this with a very realistic approach and do what I can because my No. 1 focus is affordability right now, because New Yorkers are suffering too much.”

“This is purely a political maneuver,” said Michael Hernandez, New York policy director at electrification advocacy nonprofit Rewiring America. “These Democrats” — many in districts considered flippable — “are working with fossil-fuel interests and building developers to try to delay the All-Electric Buildings Act, … a state law that was enacted through the democratic process.”

For instance, National Fuel, which supplies gas to about 500,000 households in western New York, has funded a lobbying campaign against bans on the fuel.

For her part, Hochul has a “troubling track record on climate,” said Elizabeth Moran, New York policy advocate at nonprofit Earthjustice. The governor has paused or indefinitely delayed initiatives she once championed, from congestion pricing and electric school buses to the signature policy to implement the state’s 2019 climate law: an emissions-pricing program known as cap-and-invest.

“We are seeing tremendous misinformation from the fossil-fuel industry,” Moran said. “The governor should not cave to the fearmongering of an industry that is only interested in its own profits.”

Last month, a judge found the state violated the law when it slammed the brakes on the cap-and-invest program — a case that could serve as a template should Hochul issue an executive order to delay implementing the All-Electric Buildings Act.

Hernandez pointed out that the all-electric law proceeds in a phased way, initially affecting new structures up to seven stories tall and, for commercial and industrial buildings, up to 100,000 square feet. Bigger buildings won’t be subject to the requirement until 2029.

Moreover, the law exempts projects if the grid can’t accommodate them within a reasonable window of time. The Department of Public Service has proposed that builders can use fossil-fuel systems if utility upgrades for all-electric construction would tack on 18 months or more to the development process, compared with a mixed-fuel project.

Several analyses show that all-electric buildings are more affordable than those with both electricity and gas or other fossil fuels. Building all-electric homes in New York may cost more up-front, but a 2024 state report shows the payback period is 10 years or less, thanks to the benefits of superefficient electric appliances, like heat pumps and heat-pump water heaters. Over 30 years, households will save on average about $5,000, the report finds.

A 2025 study by climate-policy think tank Switchbox that considers mortgage payments, gas hookup costs, and fuel costs, as well as the loss of federal electrification incentives, found even bigger savings: an average of $12,050 over 15 years for households living in newly built, all-electric single-family homes instead of ones heated with gas or propane.

“The Building Code Council, by law, can only update the building code if it’s cost-effective,” Hernandez said.

In their letter, the assemblymembers expressed concern about the grid’s ability to handle electrification of new buildings, citing reliability assessments from the state’s grid operator, the New York Independent System Operator (NYISO).

However, that fear is “based on a limited methodology that is not designed to identify blackout risks … and is based on a variety of extreme assumptions for which NYISO does not present factual support,” said Michael Lenoff, senior attorney at Earthjustice. NYISO’s projections “don’t justify delaying the All-Electric Buildings Act.”

NYISO uses two approaches to determine if it will be able to procure enough power for the grid in the coming years, Lenoff explained. One approach ignores common strategies to balance supply and demand, like utilizing backup systems called operating reserves, recruiting customers to voluntarily use less energy, and tapping emergency assistance from neighboring states. The method also assumes delays in major transmission projects, like the Champlain Hudson Power Express, even though NYISO reports that the transmission line “is nearing completion” and is scheduled to enter service in May of 2026.

As one might expect, this first approach paints a pessimistic picture, spurring NYISO to call for procuring more resources to supply power.

Under NYISO’s second approach — the industry standard to determine adequate power supply — the operator in fact finds that it will have plenty of planned generation resources to meet demand through 2034, even if the All-Electric Buildings Act is fully implemented. The blackout risk generally considered acceptable, striking a balance between greater security and higher costs to customers, is one event in 10 years. NYISO estimates that its risk in 2034 will be about one blackout in 20 years — twice as protective as the norm, Lenoff said. It’s even more protective in the years leading up to that.

“Procuring resources when industry-standard reliability metrics indicate the system is already overprotected risks gold-plating the system at consumers’ expense,” Lenoff said.

In its 2025 Power Trends report, which the letter directly references, NYISO also determined that building electrification is not a concern in the short term; rather, energy-hungry customers — namely hyperscalers and cryptocurrency miners — are.

“If the lawmakers are concerned about grid capacity and energy affordability, they should prioritize reining in large energy users like data centers and crypto-mines rather than cutting back on electrification,” Lenoff said.

“That’s a commonsense policy that will save people money while cutting climate pollution.”

Massachusetts lawmakers may double the number of cities and towns allowed to ban fossil fuels in new construction. A bill under consideration would add up to 10 communities to an ongoing pilot program that proponents say is already reducing emissions, making homes healthier, and lowering energy bills — all without stifling the development of new housing.

Cities including Salem and Somerville are lining up to participate in an expanded program, and some local leaders in Worcester are eager to take part, too. Boston, the state’s largest city, has previously expressed interest in joining.

“We’re a coastal community that’s going to bear the brunt of climate change,” said state Rep. Manny Cruz, a Democrat representing Salem. “We want to make sure we’re doing our part to mitigate the damage.”

As Massachusetts strives to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, it has prioritized policies that encourage the transition away from fossil fuels, particularly natural gas. In 2022, as part of a wide-ranging climate law, the state created a pilot authorizing 10 municipalities to prohibit fossil-fuel hookups in new construction and major renovations. In 2023, it introduced an optional building code aimed at reducing energy consumption and preparing for an all-electric future, and later that same year, regulators issued guidelines for natural-gas utilities to evolve toward clean energy.

Massachusetts joins other states and cities pursuing such policies. New York this summer became the first state to commit to an all-electric building standard, though Gov. Kathy Hochul, a Democrat, is now under pressure to delay the implementation of these rules. Dozens of local governments nationwide have measures on the books barring gas use in new buildings and renovations, and some have policies to ratchet down fossil-fuel appliances in existing structures over time, too.

Advocates hope Massachusetts’ pilot paves the way for the legislature to allow all 351 of the state’s cities and towns to choose their own path on fossil-fuel restrictions.

The bill still faces committee votes in both the House and Senate. Single-issue bills like this one are rarely approved by the full legislature, but are instead wrapped into a larger package, said state Sen. Michael Barrett, a Democrat and chair of the legislature’s telecommunications, utilities, and energy committee, which heard testimony on the bill late last month.

Massachusetts’ all-electric pilot has roots stretching back to 2019, when the town of Brookline passed a bylaw prohibiting new fossil-fuel infrastructure. Supporters argued that the momentum behind the energy transition and forecasts of rising natural gas prices made the policy a responsible step.

There’s no point in installing new systems now that will only get more expensive to run and will end up needing to be replaced with electric equipment before too long, said Lisa Cunningham, cofounder of nonprofit ZeroCarbonMA and one of the forces behind the Brookline bylaw.

“It’s basically locking people into these huge energy burdens,” she said.

But Brookline’s policy was struck down in 2020 by the Democratic attorney general Maura Healey, who was later elected governor of the state in 2022. Healey argued that municipalities do not have the authority to supersede state building and gas codes, though she said she supported emissions reductions and felt she had no choice but to reject the bylaw.

So Brookline and several other towns petitioned the state legislature for special permission to implement their own rules. Lawmakers responded by including the 10-town demonstration program in a sweeping climate bill that then-Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, signed in 2022 despite expressing serious reservations about the impact the pilot might have on housing.

Indeed, detractors have long maintained that all-electric building mandates will drive residential construction costs up at a time when Massachusetts is facing an acute housing shortage.

However, none of the 10 municipalities in the current program have reported such a slowdown. Lexington, for example — which has adopted both the fossil-fuel ban and the more stringent building code — has permitted some 1,100 new housing units in the past two years, including 160 affordable homes.

Research also indicates that building and running an all-electric house does not come with a price premium. A 2022 report by clean-energy think tank RMI finds that the up-front cost and annual operating expenses for a fossil-fuel-free home in Boston are slightly lower than for a mixed-fuel building. Since then, Massachusetts has adopted discounted wintertime electricity rates for homes with heat pumps, making electrification even more affordable.

“The lowest-hanging fruit is to build all-electric,” Cunningham said. “Doing all these as retrofits is going to be a lot more difficult.”

In 2023, advocates and supportive lawmakers proposed a bill that would allow any municipality to implement its own gas ban, but the measure did not make it into the climate package passed later that session.

Proponents of expanding the pilot say it is important to offer the opportunity to a wider variety of communities across the state. Of the initial 10 participants, all but two are Boston suburbs, and only two have median household incomes below $125,000. Seven have populations below 50,000, with one, the Martha’s Vineyard town of Aquinnah, home to only about 600 people.

“It restricted it to these much wealthier, much smaller, less diverse communities. That’s just not equitable,” Cunningham said.

Broadening the program will also help the state collect more data about how these prohibitions impact emissions, public health, and housing costs and availability, said Barrett, who supports the bill.

“The more data we can get in about the cost of going all-electric, the better off we’ll be,” he said.

Somerville has been eager to join the pilot since the beginning. When the program launched, it was intended to include the 10 communities that had already asked the legislature for permission to implement fossil-fuel restrictions. The creation of the program, however, spurred more local governments to vote for such bans in hopes of joining the pilot if any spots should open up. Somerville was the first to do so, just weeks after the law was enacted, with its City Council passing the measure unanimously.

Having the authority to limit fossil-fuel growth would not only move Somerville toward its goal of being carbon-negative by 2050, but also lower heating costs for some residents and create housing with better air quality, said Christine Blais, the city’s director of sustainability and environment.

“We want to give Somerville residents the best chance to have a good quality of life,” she said.

In Salem, which has also passed a measure asking to join the pilot, City Councilor Jeff Cohen would like to see the bill passed, but he also thinks it doesn’t go nearly far enough. Allowing 20 of Massachusetts’ 351 municipalities to ban natural gas just won’t make a meaningful dent in the state’s emissions, he said.

“It’s time to do something,” Cohen said. “Ten at a time doesn’t seem good enough for me.”

Massachusetts lawmakers have advanced an energy-affordability bill that opponents say would undo years of work on policies to fight climate change and promote energy efficiency, all without actually saving consumers much money.

“The bill is retreating from a couple of decades of climate progress in Massachusetts,” said Larry Chretien, executive director of the nonprofit Green Energy Consumers Alliance.

The legislation, which a House committee approved 7 to 0 on Wednesday, would make the state’s 2030 emissions target nonbinding, slash funding for energy-efficiency programming, reinstate incentives for high-efficiency gas heating systems, and limit climate and clean-energy initiatives that impact customers’ utility bills. It would also prevent projects in cities and towns with natural-gas bans from claiming energy-efficiency incentives for all-electric construction.

The bill’s author — Democratic state Rep. Mark Cusack, the House chair of the Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities, and Energy — has said these steps are necessary to get ballooning energy bills under control. Critics of the proposal, however, say this approach would trade minimal short-term savings for environmental damage and much higher costs down the road.

“We want good energy-affordability legislation. This is not that,” said Amy Boyd Rabin, vice president of policy for the Environmental League of Massachusetts. “The claim that climate policies are the thing making prices rise is just not based in fact.”

Electricity prices in Massachusetts have been trending upwards for a decade and are among the highest in the country. In May, Gov. Maura Healey, a Democrat, unveiled energy-affordability legislation aimed at saving consumers around $10 billion over the next 10 years. A hearing on the bill took place in June, but it has not advanced any further.

Cusack’s rival bill includes many of the same elements as the governor’s proposal but takes a far harsher approach to efficiency spending and climate goals. The bill still has a long way to go to become law. It would need to clear the Senate committee and be approved by both the House and the Senate, which would require support from many legislators who have previously voted for the priorities it undermines. Then Healey would need to sign it.

Still, in a state that has long been a leader in energy efficiency and climate action, the fact that the bill has gained any traction reflects the increasingly popular idea that decarbonization is at odds with affordability. This adversarial notion has gained currency in the past year as politicians and policymakers throughout the region — and the country — scramble for ways to address rising power prices. These claims, however, are simply incorrect, say climate advocates. They argue the cost of energy-delivery infrastructure and the rising price of natural gas are what’s really driving up utility bills.

Climate, energy, and consumer advocates are particularly concerned about the bill’s attempt to scale back and rework Mass Save, the state’s energy-efficiency program, which is funded by a small charge on consumers’ utility bills.

The legislation calls for cutting Mass Save’s current three-year budget from $4.5 billion to $4.17 billion, and capping spending for future triennial plans at $4 billion. These savings would, in theory, be achieved by tightening the program’s scope to focus on weatherization and lowering energy use. Mass Save would no longer be allowed to consider whether an incentive would promote decarbonization or electrification when assessing its benefits, which could put rebates for equipment such as heat pumps or home batteries at risk, advocates said.

“It essentially does eviscerate Mass Save,” Chretien said.

The charge that funds the energy-efficiency program currently makes up about 7% to 8% of the per-kilowatt-hour electricity rate from major utilities Eversource and National Grid. Reducing Mass Save’s budget by 11% would only lower that number slightly.

At the same time, Mass Save cuts costs for consumers. Those who take advantage of the incentives can save thousands of dollars on new appliances or home improvements that can then create ongoing savings by reducing energy demand. By lowering power demand, the programming also helps reduce the need to expand the grid, producing additional savings for everyone. Mass Save generated a total of $2.8 billion in benefits for participants and nonparticipants in 2024, the program administrators report.

The bill also calls for eliminating Mass Save incentives for all-electric projects built in cities and towns that are part of Massachusetts’ pilot program allowing some municipalities to ban fossil fuels in new construction.

Reducing incentives for efficient electric appliances leaves people paying more for energy-hungry systems, critics point out — even as both electricity and natural-gas prices are expected to keep rising.

“The best you could say is that it is going after short-term affordability at the expense of long-term affordability,” said Kyle Murray, Massachusetts program director for climate-action nonprofit Acadia Center. “Unfortunately, because it misunderstands the actual drivers of cost, it will drive up costs for ratepayers.”

Advocates also question the logic behind the plan to make the state’s 2030 climate goals nonbinding. Cusack argues the move is necessary to prevent lawsuits against the state, should it not meet its targets, especially in the light of obstacles being thrown up by the Trump administration. Murray, however, finds this contention unconvincing: The likelihood of a successful lawsuit is too low to justify unravelling years of climate progress, he said.

Despite the bill’s success in the House committee, opponents could still defeat it by making their case to legislators, Boyd Rabin said. And there are a lot of opponents to speak up, she said, including not just climate activists but groups concerned with municipal operations, economic development, and equity.

“I am yet to have a conversation with anyone who supports it,” she said. “I would hope legislators would listen to what they’re hearing.”

Roasting coffee requires high temperatures — up to 500 degrees Fahrenheit for as much as 20 minutes per batch. Today, the vast majority of that heat is generated by fossil fuels. Most of the world’s coffee is roasted in gas-burning machines that emit carbon dioxide and require elaborate venting and afterburner equipment.

Ricardo Lopez, CEO of Bellwether Coffee, has spent the past 12 years fine-tuning a more climate-friendly, electricity-powered alternative, one that, crucially, cuts down on some of the costs and complexities of other electric roasters.

“Our goal is to make a sustainable industry through coffee,” he said. For Bellwether, that includes working with small farms to source beans grown with environmentally friendly practices.

But Lopez, a former data-center construction manager, knows that making a new technology competitive in a crowded field takes more than good intentions. “You have to have a better product,” he said. “As long as you have a better product that’s more affordable from a cost standpoint, it can spread.”

Achieving that has taken quite a bit of ingenuity. For starters, Bellwether’s system doesn’t require the industrial-scale voltages that many European-made electric coffee roasters do. The company’s appliances run on the 240-volt or 208-volt current available in commercial buildings.

The machines also use closed-loop heat recovery to capture and filter the smoke and particulate matter that the roasting process produces, avoiding the ventilation, ductwork, and energy-intensive “afterburner” systems needed to clean up exhaust.

That makes the Berkeley, California-based company’s technology suitable for ordinary retailers. Bellwether refrigerator-sized or countertop-sized roasters are now in cafes and coffee shops in 40 U.S. states and more than a dozen countries.

“Distributed roasting means that every coffee shop can become a roaster,” Lopez said during a recent tour of Bellwether’s headquarters, which featured a sampling of some of the specialty blends sourced from farms the company works with.

That said, making the switch to roasting coffee beans in house isn’t cheap. Bellwether’s latest countertop roasters sell for $22,000, or $27,000 for its “continuous roasting” variant. This sounds like a lot, until you realize that a high-end espresso machine is about the same price, Lopez said.

And the savings from buying raw coffee beans for about $5 to $6 per pound rather than roasted beans at about $12 to $14 per pound add up quickly. Bellwether has a calculator to help determine how long it takes to recoup the up-front cost of its roasters — typical customers pay off their machines in two to 12 months, depending on the volume of coffee they roast, Lopez said. The company offers financing deals with monthly payments that can put most buyers at a cash-flow break-even point within the first month, he noted.

Bellwether’s electric roasters also appeal to large-scale roasting facilities seeking to make small-batch, high-end blends for an increasingly sophisticated coffee-drinking public. One example: the Hero collection from Red Bay Coffee, one of two Oakland, California-based industrial coffee roasters using the startup’s machines.

The closed-loop, electric roasting process is more energy efficient than traditional fossil-gas roasting — about 2 to 3 cents of energy spent per pound of roasted output, compared to about 10 cents per pound, Lopez said.

And, of course, the whole process is less emissions-intensive than relying on fossil gas to produce coffee. Roasting accounts for up to 15% of the coffee industry’s carbon footprint, and a Bellwether roaster cuts about 87% of the carbon footprint of traditional roasting, said Jonathan Bass, the company’s executive vice president of marketing and communications. That’s a significant reduction in what admittedly is a relatively slender slice of the industry’s overall climate impact, which is heavily tied to land use and deforestation.

But those emissions reductions are the end-of-day bonus to a fundamentally economic proposition, Lopez said.

“Our customers love the fact that this is the most environmentally friendly way to roast coffee, and love to communicate that to their customers. But most of them wouldn’t be able to do it if not for the quality benefits or the economics,” he said. “You’re able to take one of your highest expenses and cut it in half while having a better, fresher product that’s environmentally friendly because it’s no longer dependent on natural gas.”

Electric coffee roasters have served as niche products for small-scale craft roasters for years now. But companies like Bellwether and others in North America and Europe are scaling them up.

Bellwether’s technology has evolved over the years. Its early coffee roasters were cobbled together with steel plating and wooden two-by-fours, Lopez said during the August tour of the company’s headquarters and manufacturing space in West Berkeley. More improvements have followed since its first commercial models rolled out in 2018, including a steep cut in their initial price of about $60,000.

Bellwether has put particular effort into honing its roaster’s closed-loop heat-recovery system, which retains much of the warmth that gas-fired roasters lose in their exhaust, Lopez said. Capturing heat that would otherwise be wasted also helps control for the variables of temperature and humidity that can make it hard to achieve consistent roasting quality, he said.

Plus, Bellwether has fine-tuned the “set-and-forget” software controls that allow busy employees to program precise outputs for each batch of green coffee beans being put through the roaster, Lopez said. “The freshness and consistency of the roasting has so much impact on the quality,” he said.

Just ask Keba Konte, founder of Red Bay Coffee. The photographer-turned-entrepreneur started roasting coffee in his garage and moved into a warehouse that has housed successively larger gas-fired coffee roasting machines, including his current one capable of roasting 120 kilograms of coffee beans per batch.

In 2023, Red Bay won a $643,000 grant from the California Energy Commission to defray the cost of installing eight Bellwether machines. The undertaking did require some wiring upgrades, Konte said — but that’s a lot less onerous than designing and installing the gas lines, vents, and other infrastructure required for his gas-fired roasters.

The Bellwether machines also “allowed us to engage in another segment of the market,” he said. “We work with farmers, and our team is super-interested in these experimental coffees. … There are so many interesting things happening in the industry right now.”

It’s hard to dedicate a batch run of Red Bay’s 120-kilogram roaster to these more experimental blends. With the Bellwether roasters, “we were able to distinguish ourselves by introducing some of these small lots,” including ones from former employees who’ve struck out on their own, he said.

Konte is also exploring how Bellwether’s technology could help the company expand to new markets. Rachel Konte, his wife and Red Bay cofounder, was born in Denmark, and the couple has been looking for opportunities to expand into that country. Denmark currently charges luxury taxes on gourmet coffee imports, which made the plan infeasible.

But “if we have a Bellwether sitting there, and we import the same raw green coffee that we have here, that’s sort of a production thing — and so now, that’s just industrial ingredients. There’s no barrier,” he said. “And then the machines, because they’re already preprogrammed — we have our master roaster here making adjustments based on age of coffee, based on humidity, etc. — we can be producing our coffee, branded, in that country.”

Coffee roasting isn’t the only industry that could deploy smaller-scale, lower-carbon technologies to decentralize production. Companies are developing factory-built, electricity-powered modular systems to purify iron for steelmaking, synthesize industrial chemicals, and produce ammonia fertilizer.

Food and beverage production is a particularly appealing target, given that nearly all of the industry’s current fossil-fueled heating needs are for relatively low-temperature processes well suited to electric heat pumps, electric boilers, waste-heat recovery systems, and other lower-emissions options.

Nancy Pfund, founder and managing partner of investment firm DBL Partners, one of the lead investors in Bellwether’s $40 million Series B funding round in 2019, said mass-produced technologies like these have the potential to quickly drive down costs, similar to what has happened with solar panels and lithium-ion batteries.

“The greatest way to increase the impact of sustainable technologies is to make them, one, affordable enough to be widely adopted, not niche, and two, to achieve greater quality than approaches that are more harmful to the environment,” Pfund said.

In the case of cafes and restaurants, “that allows them to pay employees more, or pay their rents,” she said. In the case of coffee-roasting facilities, it’s “affordably reducing air pollution in communities. All of that wonderful, good stuff — and you have this amazingly delicious cup of coffee.”

The first passenger terminal for air travel in the U.S. was an Art Deco celebration of aviation. In 1935, the fearless Amelia Earhart dedicated the building at the busy airport now known as Newark Liberty International, and within a few years, hundreds of thousands of passengers were hurrying through its marble-and-terrazzo lobby to catch commercial flights.

Now an administrative center called Building One, the former terminal has made history for a new reason: It’s the first edifice owned by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, a bistate transportation agency, to undergo an all-electric retrofit.

“It’s so exciting to see [this kind of] reinvestment and making things new again,” said James Lindberg, senior policy director at the nonprofit National Trust for Historic Preservation, who wasn’t involved in the project. “Energy efficiency and decarbonization is part of that. … We know how to do it — we just need more of it.”

Buildings account for a whopping one-third of the nation’s carbon pollution. Every building — even the 80,000 structures that, like Building One, are listed in the National Register of Historic Places — must break up with fossil fuels to align with a cooler climate future.

Retrofitting any existing structure is going to be tougher than going with all-electric systems from the start. But engineers looking to upgrade historic buildings are doubly constrained by the need to maintain their charges’ distinctive architectural features; you can’t just tear down the walls of a landmark.

The Port Authority’s Building One is an early example demonstrating that storied buildings can be electrified — all while keeping their vaunted status intact.

It “was the perfect project to show the art of what’s possible,” said Dennis Pietrocola, director of operations services at the Port Authority. “If we were able to undergo an electrification transformation to Building One” — among the most challenging of the Port Authority’s structures — “then it sets the stage for [decarbonizing] the rest.”

That’s coming. The Port Authority aims to be carbon neutral by 2050, a goal that includes its entire portfolio of more than 1,000 buildings — from storage and parking structures to terminals to offices — at its airports, bridges, tunnels, railways, bus stops, and shipping ports.

Building One is the bustling home base of 190 Port Authority employees, including operations and maintenance workers, police, and firefighters. In 2023, the building’s gas-fueled equipment was ready to conk out, making it a prime candidate for a decarbonization retrofit. Pietrocola and his colleagues carefully planned a series of cost-effective electrifying updates and hired an experienced general contractor, Constellation NewEnergy, to carry them out.

The team installed five large heat pumps on the roof to provide zero-emissions heating and cooling. They put in an energy-recovery system to recycle waste heat from the locker and IT rooms. The crew added a system that can dial down power use when the grid is strained by high demand. And in the parking lot, workers installed 29 new charging ports for electric vehicles.

The team also swapped the building’s gas boilers with electric-resistance ones. Operating with the same physics as big electric tea kettles, these provide an extra boost as needed to the building’s water-based heating system. Pietrocola had considered using heat-pump boilers instead, which can be twice as efficient because they move heat instead of making it, but he nixed the idea because it would’ve meant replacing the hydronic system’s distribution pipes with bigger ones.

Workers also made some more staid updates to lower energy costs: weatherizing the building, applying heat-blocking films on the windows, and replacing more than 1,500 light fixtures with ultra-efficient LEDs.

In total, the project took 18 months and cost about $15 million — $3 million more than it would’ve had the Port Authority stuck with gas-fired equipment, according to Pietrocola.

The Port Authority didn’t use any incentives to cover the expenses, in part because the team needed to act quickly to replace the building’s worn-out systems. But federal and state tax credits are available to private entities and public-private partnerships to electrify operations as part of renovation projects, Lindberg pointed out. Unlike the consumer credits for heat pumps, EVs, and other clean energy tech, the Rehabilitation Credit was left unscathed by Republicans’ federal budget law enacted this summer, he said.

Building One’s retrofit has slashed energy use by about 25%, Pietrocola said. Still, due to the area’s relatively high cost of electricity, he doesn’t expect the structure’s utility bills to fall.

Pietrocola plans to apply the lessons learned at Building One to other Port Authority structures as their fossil-fueled systems age out, he said. He’ll approach each project with a fresh eye to the building’s particular needs and the technology available. Next time, he added, the agency may go with hydronic heat pumps instead of the electric-resistance boilers.

Decarbonizing buildings “is a very important cause to me, personally and professionally,” Pietrocola noted. Recently, he worked with his 14-year-old daughter, Kayla, on a climate-change science project. “It made me realize, well, I’m part of the problem — the way I’ve operated facilities [in the past], perhaps with a closed mind.” After guiding the electrification of one of the country’s most storied structures, he feels like he’s become part of the solution.

Time is running out for Americans to get a federally funded discount on energy upgrades that can lower their utility bills and make their homes healthier and more comfortable.

The GOP tax and spending law passed in July swiftly phases out tax credits that help households afford heat pumps and other energy-saving electric appliances. The credits were supposed to last about a decade; now they sunset Dec. 31.

To meet this use-it-or-lose-it moment, electrification advocacy nonprofit Rewiring America last week launched the Save on Better Appliances campaign. It’s a nationwide effort to help homeowners and renters lock in the incentives — the Energy-Efficient Home Improvement Credit (25C) and the Residential Clean Energy Credit (25D) — before they’re gone.

“Most people don’t think about this stuff every day,” said Ari Matusiak, CEO of Rewiring America. “We’re talking about five or six purchasing decisions that you make only several times over in your whole life. … So making sure people have the resources and information available about [this] technology that is better and can save them money, is really important.”

The tax credits enable households to save thousands of dollars on their federal taxes when they invest in energy-slashing home upgrades, including electrical panel retrofits, weatherization improvements, and installations of solar panels, heat pump heater/air conditioners, home batteries, and heat-pump water heaters.

Such measures are especially salient as households grapple with inflation, tariffs, and rapidly rising electricity costs. President Donald Trump promised to lower power bills, but experts expect his administration’s anti-renewables agenda will keep them climbing.

Efficiency upgrades also help put a dent in planet-warming pollution. More than 40% of U.S. energy-related emissions stem from how people heat, cool, and power their homes and fuel their cars, according to Rewiring America.

With the long lead time often needed to get quotes and book contractors, households realistically need to decide if they’re going to pursue clean energy projects in the next several weeks to get the federal discounts, Matusiak said.

Accordingly, the campaign, which runs until the end of October, is a full-court press of resources and tailored support. Rewiring America is also coordinating with elected officials, manufacturers, utilities, and grassroots groups on the effort. Among those partners is the U.S. Climate Alliance, a bipartisan coalition of 24 governors, which last month committed to helping constituents take advantage of the tax credits.

“It’s really disheartening to see the federal government take away financial assistance from Americans at a time where they need it more than ever,” said Casey Katims, U.S. Climate Alliance executive director.

Rewiring America has set up a central hub where homeowners and renters can launch their electrification journey. The nonprofit’s Personal Electrification Planner allows users to estimate how much an upgrade is likely to cost up front and save them on their energy bills over time. Individuals can also search for independently vetted contractors and look up incentives with the nonprofit’s savings calculator, which lists federal as well as local rebates and tax credits in 29 states.

For people looking for more support, Rewiring America is holding weekly drop-in Zoom sessions with certified, trained “electric coaches.” They’re volunteers who can offer free, impartial guidance to help people troubleshoot the gnarly complexities of making energy-efficient home upgrades. The first session is on Wednesday, Sept. 3.

Rewiring America is also securing deep discounts on heat pumps for homeowners — in Rhode Island and Colorado, to start. The organization has teamed up with manufacturers and contractors to drive costs 20% to 30% below standard market pricing by pooling customers together — an approach national nonprofit Solar United Neighbors has used for years to get better deals on solar panels. A Rewiring America spokesperson declined to specify how many households have enrolled so far.

Rewiring America had longstanding relationships that made these two states particularly fertile testing grounds, Matusiak said. But if it succeeds, the organization plans to expand the group-purchasing initiative. In a few places, others are also leveraging collective market power, including installer Vayu in the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles and Laminar Collective in the Boston metro area.

Overall, “the goal here is to create broad awareness for people to take advantage of incentives that are theirs to take,” Matusiak said. For individuals open to going electric, “we hope they access our resources — and do that right away.”

At the end of June, California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) signed into law AB 130, a sweeping bill that aims to make it easier to build housing, reforms that many lawmakers and experts agree are long overdue given the state’s severe housing crisis.

But one provision could needlessly slow the state’s progress on its climate and clean energy goals, according to advocates. The law pauses updates to state and local building codes — the mandatory construction standards meant to ensure that new buildings are safe and energy efficient — for the next six years.

Buildings account for a quarter of California’s carbon pollution. And the state’s building standards, which are normally revised once every three years, have been a powerful decarbonization tool. The latest statewide energy code, already finalized, takes effect Jan. 1, 2026, and encourages developers to build all-electric homes with both heat pumps and heat-pump water heaters — super-efficient, zero-emissions appliances that are safer than gas-fired options. In addition to updating codes, California has eliminated subsidies for new gas lines.

These regulations are working; “California is an electrification-forward state,” said Sean Armstrong, managing principal of Redwood Energy, a design firm specializing in net-zero, all-electric affordable housing development. In 2023, 80% of line extension requests by builders to utilities Pacific Gas & Electric and San Diego Gas & Electric were electric-only, according to the California Energy Commission, the agency responsible for developing the building energy codes. The commission expects that the majority of new houses built under the latest code will be all-electric.

Now, though, the state will skip a scheduled 2028 residential code update, blocking it from pushing builders to go further to cut emissions. Starting Oct. 1 this year, the new law will also prevent local jurisdictions from updating their own, more ambitious building standards, known as reach codes.

These could include measures not yet enacted in the state rules, such as encouraging heat pumps for multifamily buildings, mandating all-electric renovations, and requiring that broken central air conditioners be replaced with heat pumps that can both warm and cool spaces. That last idea is an inexpensive way to decarbonize heating, according to Matt Vespa, senior attorney at nonprofit Earthjustice.

Seventy-four local governments in California have passed reach codes that encourage or require all-electric new construction. With the pause on updates looming, San Francisco is now racing to get an all-electric requirement for major renovations on the books before the Oct. 1 deadline.

AB 130 does allow for some exceptions that could let local governments implement stricter building requirements even after the cutoff date.

The law permits the state commission and local governments to update building codes in emergencies to protect health and safety. Perhaps the climate emergency will qualify, said Kelly Lyndon, cochair of the advocacy alliance San Diego Building Electrification Coalition.

Cities and counties can also adopt updates that are necessary to carry out greenhouse gas emissions reduction strategies spelled out in their state-mandated general plans. These road maps must have been adopted by June 10, 2025, and code updates can’t ban gas.

“At least one of these exceptions is going to work for folks who want to make further progress on climate,” said Merrian Borgeson, director of California policy with the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Climate & Energy Program. “Unfortunately … [AB 130] makes it more complicated and creates more red tape.”

Vespa pointed out that many jurisdictions may be able to take advantage of the exception for preexisting aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Among the 482 city plans, 409 mention “greenhouse gas” — an indicator that local leaders are pursuing emissions cuts. The phrase also shows up in 52 of 58 county general plans.

Sacramento’s general plan, for example, stresses “a continued focus on improving the performance of both new and existing buildings.” A local code update to swap old air conditioners with heat pumps could fit within AB 130’s exemption, Vespa said.

But it’s too soon to say who might try the strategy first. “Some jurisdictions are really looking towards their legal experts to interpret [the exception language],” said Madison Vander Klay, senior manager of government affairs at the nonprofit Building Decarbonization Coalition.

But even with its exclusions, the moratorium “is a big problem for emissions, affordability, and cost savings,” Vander Klay said.

Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas (D) and Assemblyperson Nick Schultz (D), who authored the initial standalone bill to pause building codes, AB 306, championed the idea as a way to help solve California’s housing affordability crisis and spur rapid recovery after the wildfires that torched areas of Los Angeles County in January. That bill eventually got folded into AB 130.

“California home prices are double the national average, and the rent is too damn high. So many folks cannot afford to live in California,” Schultz said on the Assembly floor in April. “This pause … will provide stability and certainty in the housing construction market by temporarily freezing the standards by which people need to meet to construct their home.”

It’s unclear whether the bill will actually make homes more affordable, though. “Building codes have never been what drives high costs in California — certainly not the energy code,” Borgeson said.

A 2015 study conducted by the University of California LA for Pacific Gas & Electric backs that up; the authors noted that they couldn’t find a statistically significant relationship between California’s energy-efficiency code and home construction costs.

“There isn’t a lot of evidence that waiving codes helps affordability,” Vander Klay said. “The building codes overall are required [by law] to be cost-effective.” Any up-front costs must be outweighed by savings.

The standards have delivered, sparing Californians more than $100 billion in avoided energy costs over the last five decades, according to the Energy Commission. The code that takes effect next year is expected to net more than $4.8 billion in savings over 30 years.

Research also shows that building all-electric homes is typically faster and cheaper than building those with gas. A 2019 analysis by energy consultancy E3, for example, estimated that building a new all-electric home in most parts of California costs about $3,000 to $10,000 less than building a home that’s also equipped with gas. Similarly, a 2022 study by the New Buildings Institute found that constructing an all-electric single-family home in New York costs about $8,000 less than a home with gas. A UC Berkeley team used these and other findings to conclude in an April report that the most cost-effective way to rebuild after the LA fires is likely all-electric.

With the moratorium, the commission will have to skip the 2028 residential code cycle. That omission could result in tens of millions of dollars in lost utility bill savings for households, according to the Building Decarbonization Coalition. Notably, the commission will be able to work on the following code update, so it can take effect as planned in 2032.

In the wake of AB 130, the Building Decarbonization Coalition’s Vander Klay is urging the Legislature to reauthorize California’s successful cap-and-trade program to support home electrification by making heat pumps and other decarbonizing tech more affordable. “There is still an opportunity … this year for the state to look at carving out funding to provide incentives,” she said.

In passing AB 130, state lawmakers took aim at rules that they contend stifle development. Underpinning this strategy is a notion popularized by a recent book, “Abundance.” Authors Ezra Klein of The New York Times and Derek Thompson, contributing writer at The Atlantic, make the case that well-intentioned but overly protective regulations can foster scarcity — in this case, of housing — and thus interfere with leaders’ ability to deliver on the promises of a better life.

But Vander Klay argues that lawmakers should view strong building codes as a way to help create abundance. “Abundance is this idea that we should all have access to housing, we should all be able to afford our energy bills … we should all be able to have access to clean air and clean water and healthy homes,” Vander Klay said.

Clean energy technologies like heat pumps are part of an abundant, safer, more climate-resilient future, she noted. “We have building codes as a tool to support building what we need safely and quickly and affordably.”